With Archaeoacoustics, Researchers Listen for Clues to the Prehistoric Past

Investigators in this small, emerging field make noise in caves and measure resonance.

Iegor Reznikoff shows no self-consciousness as he imitates the sound of a prehistoric bison in the middle of a Parisian hybrid café and Chinese restaurant. And frankly, no one seems to pay him any mind.

Reznikoff, a tall man dressed all in black, has the look of a musician, which he is. He is also an early pioneer in a field that has become formally known as archaeoacoustics, or sound archaeology. He is explaining his process for exploring prehistoric painted caves, a mix of systematic measurement and vocal experimentation.

Archaeology aims to infer things about the behavior of people of the past, mainly working back from physical structures and objects. Archaeo-acousticians want a sense of how the past sounded. Their methods include the careful examination of sites, known to have been used by humans, for clues about rituals performed there that might have included sound. They may also generate sound on-site to then measure the resonance or the echoes in a space.

Some use scientific instruments and mechanically produced audio to do that. Reznikoff is more old-school. A classical pianist with a PhD in mathematics, his first passion was early Christian music and chant. An expert on the structure and acoustics of Romanesque and pre-Romanesque churches, he visited his first prehistoric cave in the winter of 1983 with Michel Dauvois, who studied prehistoric sites and artifacts. Dauvois had heard one of Reznikoff’s recordings from a 12th-century abbey and was interested in getting his take on a prehistoric site.

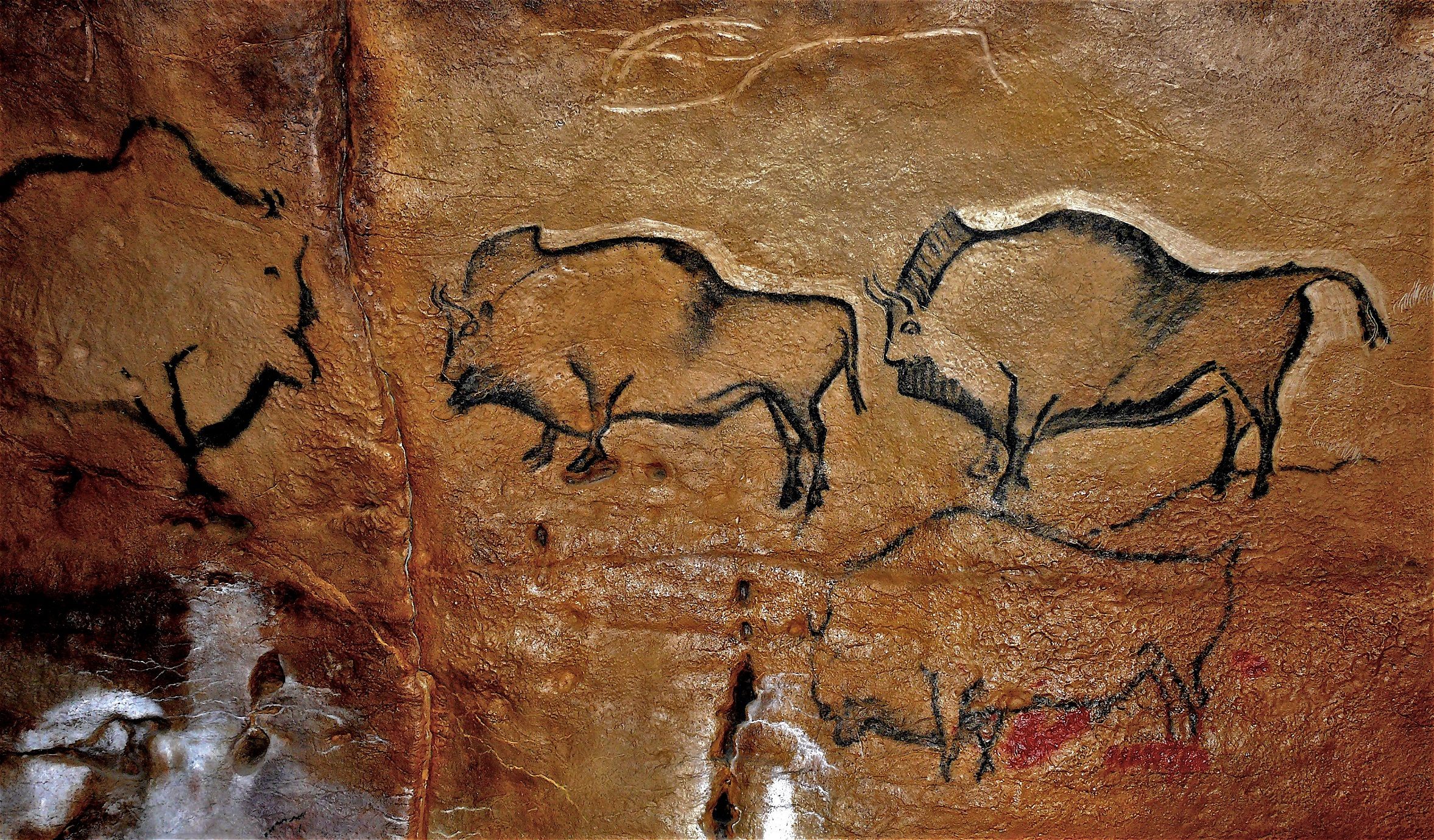

The two visited the Grotte de Portel, a painted cave in the south of France near the Spanish border. The site had been discovered in 1908 by French naturalist Rene Jeannel, who would go on to become director of France’s national museum of natural history. At the time Revue Prehistorique reported on his finding of 40-odd paintings in black or red, mostly of animals but also two human figures—an unusual inclusion, according to the journal.

Upon entering the cavern, Reznikoff recalled, “I started to hum.” With this, one of his favorite low-tech tools, he established that certain parts of the cave have richer sound than others. He also thought he noticed another pattern. The placement of the images on the walls, it seemed to him, clustered around the most resonant points in the cave. This marked for Reznikoff the beginning of what would become decades of research into the acoustic properties of prehistoric sites.

Studying something as ephemeral as sound in prehistoric environments comes with a great deal of uncertainty. It relies on inference and interpretation.

“If you come to a room with good resonance,” notes Reznikoff, it doesn’t necessarily “prove they historically used resonance.” His goal has been to find some kind of evidence that those sound properties were noted by prehistoric visitors.

Archaeologists, Reznikoff’s sometime-collaborator Paul Devereux likes to say, used to look at the past as a silent movie.

“The idea of soundtrack came later,” says Devereux, whose current main project involves prehistoric tombs in the UK. Research on sites’ acoustic properties was initially sporadic, often poorly coordinated and considered somewhat fringe. The term “archaeoacoustics,” with its accompanying air of respectability, only dates back to 2003, he notes.

While sound might leave traces—indentations where a ringing stalactite has been repeatedly struck, or even the remains of instruments—these are rare finds. For Reznikoff, his key method has been to look for correlation between resonance and man-made markings, which he has continued to document across multiple caves in France, Italy and Spain. His theories as to why this occurs include both ritual purpose and a type of navigation involving human echolocation. He’s also interested in niches which, he says, resonate in particular ways that seem to mimic animals painted nearby.

But even the facts open to interpretation come with major caveats. It’s difficult to confirm that a space still has the same acoustics as it did at the time it was used. Earthquakes or erosion may have shifted the landscape. Some caves have been modified to accommodate modern visitors. At his burial ground research site, Devereux has to worry about changes that might have occurred during its use as more bodies were interred.

Then there is the debate over the “modern performance,” as Devereux refers to it. Needing to “experience the way a site itself behaves acoustically,” some researchers generate this sound using machines: something emitting a tone at a steady frequency, or fluctuating predictably.

Reznikoff is openly dubious about the use of tools like sound pistols to measure things like echoes. While they may offer more consistency repeated time after time, Reznikoff maintains sites should be tested as they would have been experienced in prehistoric times, notably with the human voice and the human ear. (He does use audio editing software to study the recordings he makes.) Reznikoff defends his approach, considered unscientific by some, as “anthropological.” The connection between niches in the walls and nearby animal paintings, he presents as an example, depends on interpretation and intuition. A machine would not see the space in the same way.

However, his methods make his findings difficult to replicate and to defend to skeptically minded audiences. Much of the existing caution around archaeoacoustics is around the level of certainty that can be achieved about its findings.

Certain practitioners veer into the high speculative: there are hypotheses, for example, about universal frequencies recurring across widely dispersed sites because of some deeper physiological resonance. Another of Devereux’s long-time collaborators, Robert Jahn of Princeton, also founded the Princeton lab that conducted research on ESP until 2007.

“I don’t want to sound like I’m denigrating people’s approaches,” says Chris Scarre, diplomatically, but some of the work in the field is, “floating a bit far away from being able to be able to pinned down in secure evidence.”

Scarre, professor of archaeology at Durham University in the UK and co-editor of the 2003 volume Archaeoacoustics points out that more researchers than in other areas of archaeology may have come from other disciplines. Musicologists or ethnologists may approach their research in different ways.

“The trouble with archaeoacoustics is it’s always suffered with not having enough critical mass to create a sort of methodological rigor,” he says.

The field has been developing over the last 15 years, he notes, including simply the development of better communication between practitioners. However, “it’s difficult to work from what we’ve got to what we’d like to have,” namely a secure and consistent basis for a challenging area of research.

Scarre is, unsurprisingly, an advocate for a common standard for sound production and recording. He has, incidentally, also done research using mechanically generated sound on painted caves in Spain. His team, he said found “not strong correlation but some correlation.”

He compares the field’s growing pains to that of archaeoastronomy, another relatively new subset of archaeology. Archaeoastronomy involves the study of how ancient peoples viewed and studied the skies. The most basic example is the alignment of Stonehenge and the rays of the sun at the summer solstice, which suggests that those who built it had an understanding of astronomical phenomena. Theories can get much more complex.

People have shown Scarre incredible correspondence on paper, he says, but it’s another thing to prove they were perceived at the time. Likewise with sound archaeology.

“I’m not negative. I’m cautious,” he says of the research to date. “Can we persuade a skeptic?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook