How Arrow-Wielding Men Mapped Britain in the 1940s

Recently unearthed photos show beleaguered surveyors in suits holding pointy wooden markers.

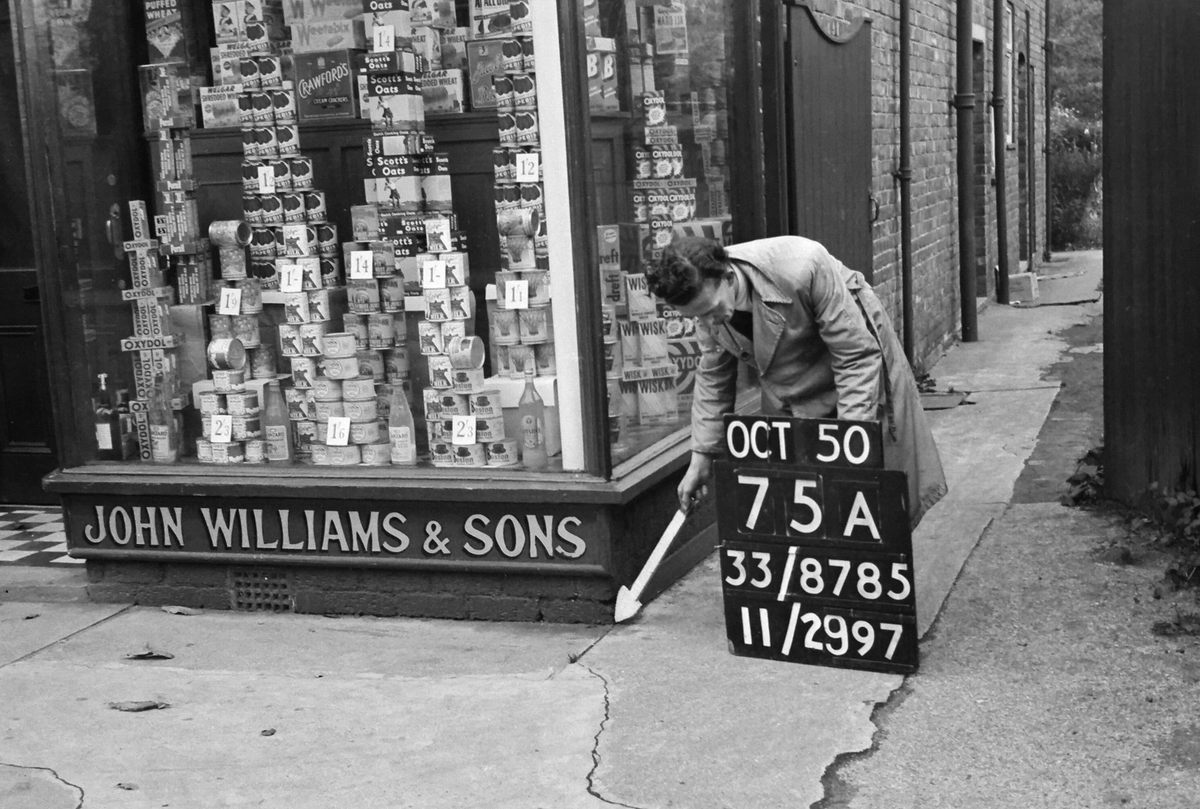

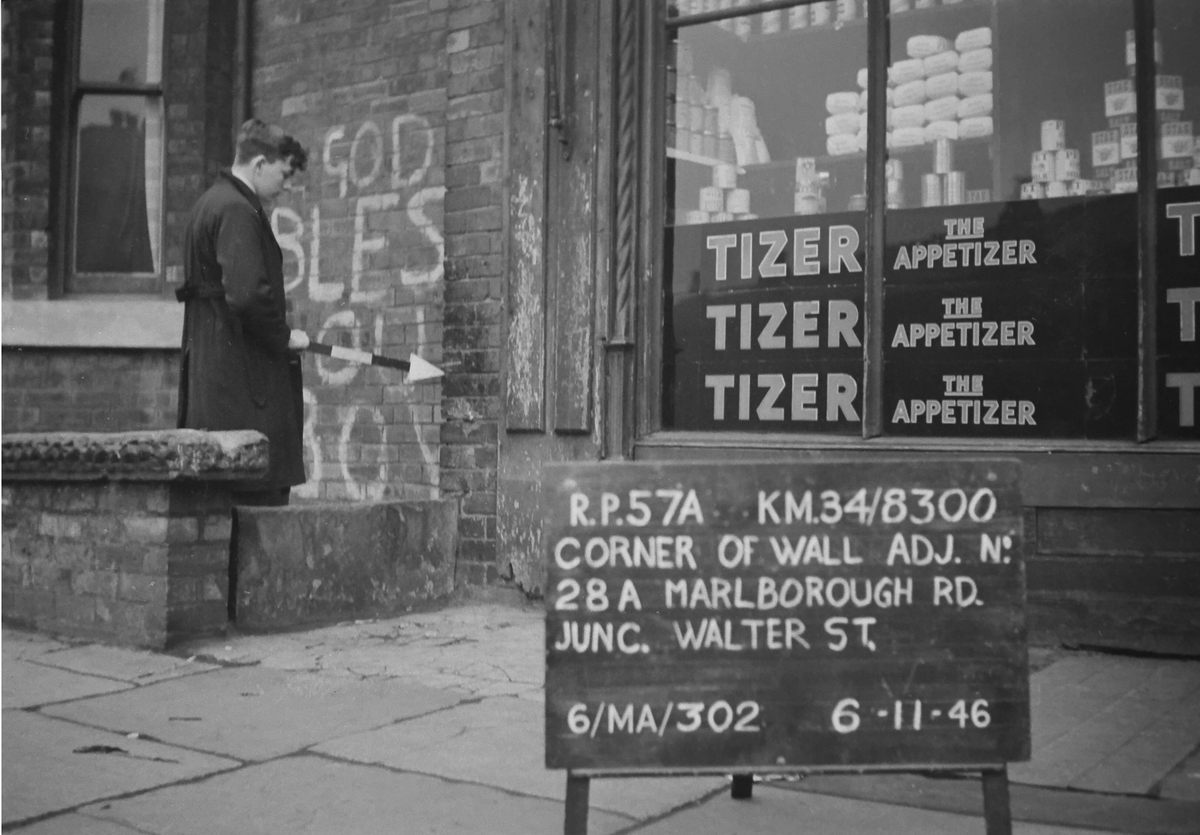

On March 11, 1947, readers of the Manchester Evening Chronicle were warned of a strange invasion. “Teams of men have descended on a dozen cities,” the article explained. Some of these men wielded scopes and tape measures. Others had cameras, wooden boards, and cartoonish two-foot-long arrows, like the one pictured above.

Citizens were to cooperate: if the men asked to enter your home or workplace, or point one of those arrows at your stone wall, “you shouldn’t say no,” the Chronicle continued. After all, silly props notwithstanding, these men were pulling off a serious feat. They were mapping all of Britain, one revision point photo at a time.

As Ordnance Survey employee Elaine Owen explains, urban surveyors based their maps off of small, unmoving features of the built landscape, called “revision points.” The photos kept track of where these anchors were located. They were vital resource in the midcentury effort to make detailed maps of Britain’s major cities, but as technology changed, they eventually fell out of use. Manchester’s languished in boxes for decades, until an archivist at the city’s Central Library showed them to Owen.

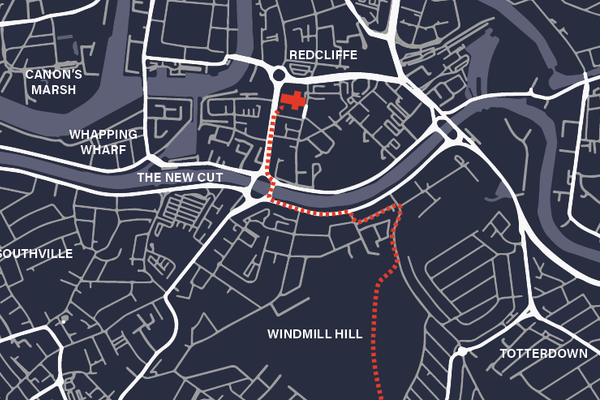

Earlier this month she scanned and uploaded about 23,000 of them to inaugurate her new website, Timepix, which uses maps to place historic photos in their geographic context. “Manchester was one of the first cities to be mapped,” says Owen. Seventy years later, you can use these photos to travel back in time and walk its streets, with the survey workers pointing the way.

Nowadays, if people need precise geographical information, they generally turn to satellites. But before such technology was available, mapmaking required a tiring combination of trigonometry and hoofing it. When new maps were necessary, teams of surveyors would roam the country, choosing or building landmarks and measuring the angles and distances between them. Cartographers and draughtsmen would take the data they collected and transform it into precise charts.

Great Britain’s first major surveying project, the “Principal Triangulation,” began in 1791 and took over half a century to complete. During that time, surveyors from the Board of Ordnance established a series of “triangulation stations,” each of these stations denoted by a large stone with a deep hole drilled into it. The surveyors who installed and measured from the stations wrote down variously detailed accounts of where they were, and did their best to use non-local stones for the markers, to enhance their visibility.

Though undoubtedly clever, this method had some shortcomings, which became apparent when it was time to update the maps. “The descriptions were very poor and varied in quality … from a dimensioned plan to a statement such as ‘Mr. Brown who lives in the cottage at the foot of the hill knows the position of the station,’” a later report explained. “After a lapse of 100 years or more and the consequent demise of Mr. Brown this naturally complicated the task of finding such stations.”

In other cases, civilians accidentally destroyed the markers: the report mentions a cinema owner removing one to install a “Wonder Organ,” an archeologist excavating another, and a policeman throwing one away because he thought it was part of a zeppelin bomb.

And so in 1935, when the country underwent an update (called the “Retriangulation”), the Ordnance Survey decided to do things a bit differently. First, they installed durable concrete obelisks, known as “trig pillars” or “trig points,” on various hilltops and mountains across the country. The trig pillars doubled as stands for surveying instruments known as theodolites, and the surveyors used them to establish the initial, or primary, triangles. They then broke those down into smaller and smaller zones, their axes denoted by other markers: generally brass rods, bolts, or buried concrete blocks.

At the most fine-grained scale, though, even those were too clunky. “The cities were mapped in more detail than the countryside,” says Owen. So in urban centers like Manchester and London, surveyors decided to find existing fixed spots instead of making them, establishing what they called “revision points.” For these, they sought both specificity and longevity. A quintessential revision point might be a scratch on a wall, or the corner of a doorway, or an old nail sticking out of a post—something so ordinary, unchanging and small, most people wouldn’t even notice it.

This is where the props come in. These surveying teams wanted to ensure that when their own successors set out to revise the map, they wouldn’t have to spend hours searching for the right scratch, corner, or nail. So every time they deemed something a revision point, they recorded the date and a location code onto a wooden board. They then had someone point a big arrow at the point in question, and snapped a photo.

“They’re concentrating very hard at where they’re pointing, because those points are at centimeter[-level] accuracy,” says Owen. “They need to get the arrow right on the point.”

Clicking around the Timepix map, you can get a sense of how a typical surveying team’s day might have gone. The black board—called a hymn board, after the church prop it resembled—was heavy, and difficult to haul around. The cameras must have been cumbersome as well. Despite this, the workers often dressed in collared shirts and jackets. Sometimes they even wore ties.

“The nature of the survey is that it is ordinary places that are captured,” says Owen. “Major public buildings and places tourists might normally go are of far less interest than the humble street corners.” Some afternoons took the teams down empty streets, where they aimed their arrows at building after building. Others they spent on lonely back roads, stoically pointing up at a railway bridge, and then down at the corner of a drain.

As other Mancunians went about their own days, intersecting with these roving men must have been confusing. Part of the point of that 1946 Chronicle article was to explain the project to the general public. (It even includes an appeal from the surveyors: “Please don’t move our tripods.”)

But even so, Owen says, “a lot of people had no idea what was going on.” In a fair number of the images, the arrow-pointers are dogged by curious onlookers—or, occasionally, actual dogs. Pedestrians gawk, children photobomb, and shopkeepers come out to see what’s what.

Once the survey was finished, the photos were collected into thick books and stored in Ordnance Survey offices. Up until the 1980s, Owen says, people would still refer to them. But after satellite technology made them obsolete, they were all donated or destroyed. “They were a really valuable part of our history and we basically threw them away,” she says. (The arrows and hymn boards, unfortunately, are also nowhere to be found.)

She feels lucky to have found the Manchester revision point photos, and is excited to dig into another store, of about 300,000, that was recently unearthed in an Ordnance Survey building. There are probably other troves in local archives and record offices, too, just hanging around and waiting to be mapped.

In the meantime, this set is a good start. Now that the images are online, Owen hopes that some of these photobombing children will recognize themselves in one of them and come out of the woodwork. So far, she says, she’s in touch with one man, who has been combing through the collection: “His dad was a surveyor, and he’d go out with him on school holidays and help out, and if he was good they’d let him point the arrow.”

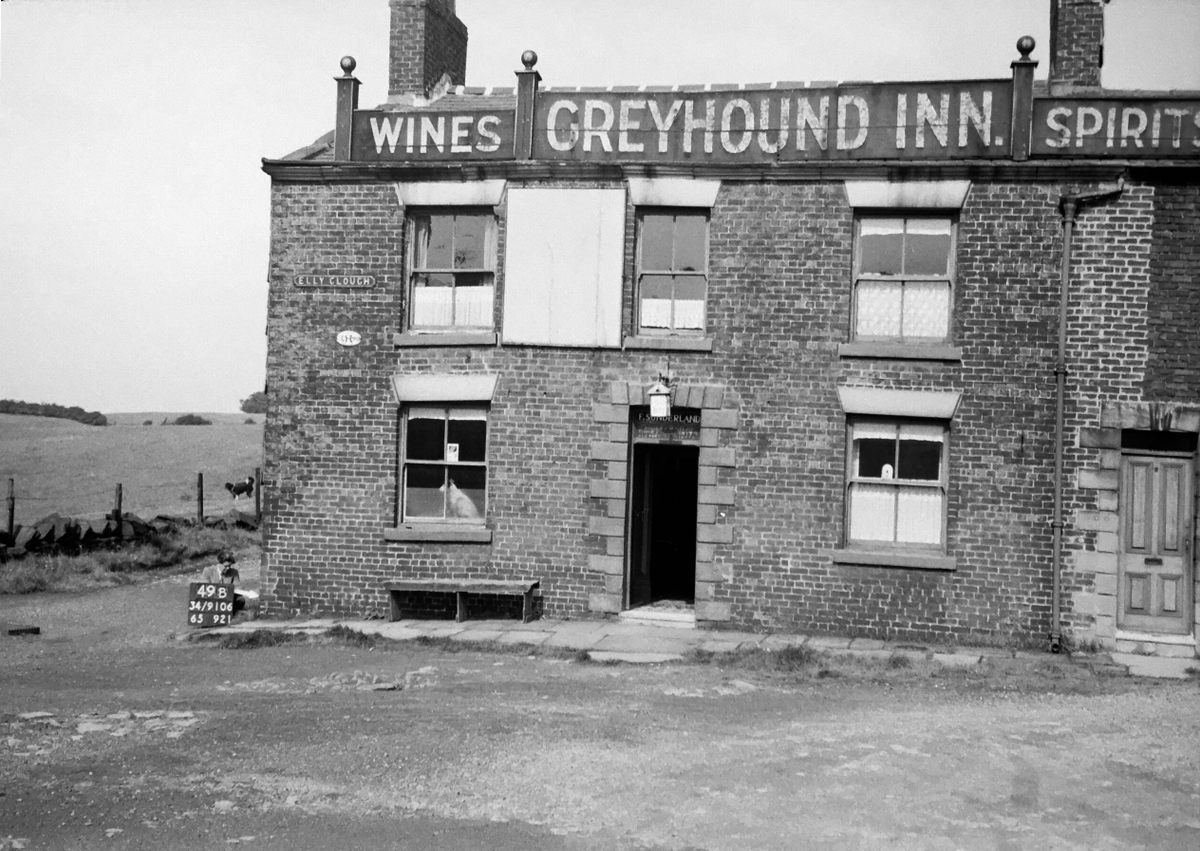

The owners of a pub, the Greyhound, also got in touch after spotting their building. Unlike the children, it looks almost identical to its 1940s portrait, save for the new parking lot and picnic tables out front.

Owen also hopes people enjoy the quotidian details the photos provide: the fashions, the advertisements, and other aspects of the everyday. While trying to gather ageless data for an abstract map, the surveyors happened to thoroughly capture a very particular time and place.

A few more of Manchester’s revision point photos are below. You can find tens of thousands of them at Timepix.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook