Atlas Obscura’s Guide to Precarious Places

A celebration of places giving gravity the finger… at least until gravity fights back.

Part I: Feats of Faith

The Kyaik-htiyo Balancing Pagoda - Myanmar

The Golden Rock Pagoda, or Kyaik-htiyo, is an extravaganza of balancing feats consisting of a pagoda on top of a huge rock that is itself teetering on the edge of a cliff. The relatively small pagoda was built atop a gilded 25-foot-tall, egg-shaped boulder during the time of Buddha for the purpose of enshrining a hair relic from His Holiness himself. Theoretically the monk to whom the relic bared most import requested that location due to the boulder’s resemblance to his own head, where he fancied storing the relic on his person. Moreover, the golden boulder is perched on an inclined plane leading to the edge of a precipice, with only a very small contact area between its base and the smooth slab of granite beneath. Despite having weathered more than 2500 years worth of earthquakes, the forces preventing the boulder-pagoda pair from crashing below remain unclear.

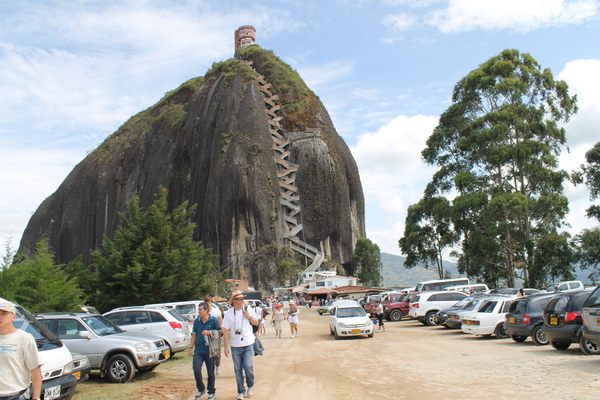

El Peñon de Guatape’s Lookout Tower - Colombia

El Peñon de Guatape’s Lookout Tower - Colombia

Sometimes the most frustrating thing in the world can be as simple as a huge goddamn rock.The perfect example is El Peñon de Guatape in Colombia’s plains. Until the 1900’s, the 10-million-ton rock did nothing for locals except get in the way of their perfectly tilled fields. It took until 1954 for a crew of intrepid youth to summit El Peñon over the course of five days, supposedly using nothing more than wood planks lodged in the lone crack running up one side of the behemoth. Today a zipper-like staircase zigs and zags its way up all 7,005 feet o the mountain, where a three-story lookout tower provides spectacular views of lakes and islands. The top of El Peñon is rounded at the edges, so sticking as near to the center of the peak as possible is advised.

La Iglesia de los Remedios - Mexico

La Iglesia de los Remedios - Mexico

Built in the early 17th century during Hernán Cortes’ conquest of Mexico, according to one version of history, the church’s location was selected because it was the largest hill in the region of Cholula. History number two suggests that the Conquistadors chose to literally and physically assert their faith’s dominance by erecting Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in this spot because this “hill” is actually the world’s largest pyramid, a temple built to honor the “pagan” Quetzalcoatl. Archaeologists have been digging away at the Aztec temple since 1931, meaning that the church, already perched precariously atop a freaking pyramid, is losing more of its base every year. Last time the Atlas visited Cholula, and the chapel had been closed due to concerns with the chapel’s structural integrity, though it appears to be open and functioning again as of 2011.

photograph by Jaime Pérez

Meteora’s Monasteries - Greece

The Greek Orthodox monks have a history of making their refuges as difficult to access as possible. Religious persecution drove devotees to nearly inaccessible heights as a means of self-preservation. Only after the conquest of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans did the monasteries of Meteora (alternately translated to mean “the heaven above” or “hovering in the air”) begin to thrive. Until the 1920’s, these spiritual enclaves remained accessible only by being hauled up the spire faces in a large basket drawn by a series of ropes and pulleys, whose lines were only replaced “whenever they break.” Faith indeed! Nowadays visitors may climb stairs carved into the cliffs for a small fee, though women are required to wear long skirts or trousers for practical as well as religious reasons.

Takasugi-an - Japan

Takasugi-an - Japan

Leave it to modern architect Terunobu Fujimori to find the middle ground between Salvador Dalí and traditional Japanese architecture. Located in Chino, Nagano prefecture, Takasugi-an is a classic tea house built atop a precarious-looking set of chestnut stilts. The one room domicile was constructed entirely by Fujimori’s own hands, complete with free-standing ladders for ascent. Short of its height, the treehouse/teahouse and its visitors ahdere firmly to protocol. Shoes are to be removed half-way up the ladders, and everyone congregates on the bamboo lined floors for their tea, which is steeped over a wood fire. The project is aptly named Takasugi-an, which translated means “a tea house built too high.” You don’t say!

Tigers Nest Monestary - Bhutan

Tigers Nest Monestary - Bhutan

Clinging to the side of Bhutan’s cliffs is a Buddhist monastery so difficult to access that it is said the founder himself ascended to just such a perfect spot via a concubine-turned-flying-tiger. For those of us without such fabulous transport, reaching the Tiger’s Nest is markedly less easy, and may merit adopting the mentality that great struggle ahead of time will be met with equal payoff later. The climb to the monastery requires ascending stairs to a total height of 10,000 feet above sea level, of which the last thousand or so are carved directly into the stone face of the mountain, sans handrail, and treacherously cross the base of a 300-foot-high waterfall plunging from the canyon’s side. The views and solitude at the top are, of course, unparalleled, otherwise who would bother?

St. Michael of the Needle Chapel - France

St. Michael of the Needle Chapel - France

On rare occasions, a traveler reaches a point where he comes face-to-face with the fact that he has successfully gone as far as possible. Such was the case of Bishop Godescalc from the tiny French village of Le Puy-en-Velay. Upon returning in 951 from his first pilgrimage along the now-famous Santiago de Campostela trail, Godescalc took advantage of a teeny plot of vacant land atop his hometown’s volcanic plug where he built a chapel to “Saint Michael of the Needle.” To this day, pilgrims just setting out on the Santiago de Campostela mount the 268 stone steps to have their walking sticks blessed in this lofty, albeit minute, holy site atop the remnants of an ancient French volcano.

Part II: Erradic Erosion

Ischigualasto - Argentina

Ischigualasto - Argentina

In a remote corner of northwestern Argentina lies the world’s foremost remnants from the Earth’s ancient history, a collection so unique that it has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Paleontological draws include prominent dinosaur and mammalian fossils, but the most unique feature in the badlands of Ischigualasto or “The Valley of the Moon” is its complete, undisturbed sequence of Triassic rock deposits. Top-heavy stone masses loom on the horizon, their bases continually being carved away by steady winds rushing through the high desert plains. Prominent formations include “The Sphinx,” “The Worm,” and “The Mushroom,” all of which continue to defy gravity despite rising amidst one of the most tectonically chaotic regions on Earth.

.jpg) Brimham Rocks - England

Brimham Rocks - England

In North Yorkshire, England lies an expanse of rock formations so absurd in shape and size that it’s beyond imagination that they don’t collapse into a pile of detritus in the slightest breeze. It was previously thought that the Druids were responsible for the formations, some of which reach heights of 30 meters and are spread out over 400 acres, until modern geology led us to understand that glaciers – not pagans – are responsible for “Idol Rock” (pictured above), “The Watchdog,” and more. The public is permitted access on a daily basis, though only the most experienced rock climbers are encouraged to attempt their faces.

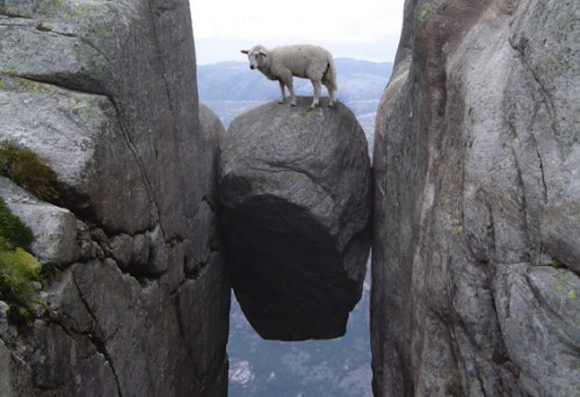

Kjeragbolten - Norway

Ever heard the expression “Stuck between a rock and a hard place?” The figurative becomes literal at Kjeragbolten. High in Norway’s mountains near Lysefjord, a boulder the size of a Mini Cooper is wedged between two sides mountain cliffs. Hikers and mountain goats alike use the dangling rock as a photo opp, while daredevils use it as a literal jumping-off point; Kjeragbolten is a popular base jumping site due to the more than 3,000-foot drop surrounding the boulder on all sides. Visitors aren’t prohibited from testing their mettle out there above the crevasse, but it should be noted that not all balancing objects remain so…

Part III: #FAIL #GravityAlwaysWins

The Twelve Apostles - Australia

The Twelve Apostles - Australia

One of the most frequently visited attractions in Australia is a series of nine – now, seven – limestone pillars confusingly called The Twelve Apostles (apparently math is relative in Australia). You see, apostle number nine, turnip-shaped and teetering in the waves had a rough go of it a few years back.

As a family of tourists happily snapped away, the process of erosion came to its logical conclusion: the nearly 150-foot-tall pillar imploded into nothing more than a pile of rubble in the waves (see foreground of above picture). Recently apostle number eight offed itself in a similarly dramatic fashion. Previously a land bridge that connected a pillar to the mainland collapsed, leaving a pair of tourists waving frantically for help on the newly autonomous landmass. And what was the name of that former natural bridge? Why, the London Bridge, of course!

.jpg) Logan Rock - England

Logan Rock - England

Built into one’s appreciation of balancing objects is the understanding that at some point something’s gotta give. Surprisingly, one of histories more notableturns out not to have been the result of natures inexorable pull but of that of unstoppable force: a bunch of angry dudes.

Perched atop the ocean-side cliffs in Cornwall is an 80-ton boulder that the Good Lord was said to rock at the “gentlest touch” bestowed by man or breeze. Locals had also touted that “it is morally impossible that any lever, or indeed force, however applied in a mechanical way, can remove it from its present situation.” This remained the case until 1824 when the British Navy arrived to install a buoy off-shore in notoriously treacherous waters.

After along day of struggling against the sea, Lieutenant Goldsmith and his men let their testosterone get the best of them. “Morals be damned,” they (probably) said, “we’re gonna show that rock not to mess with the men of the HMS Nimble.” Using nothing more than the aforementioned levers and bars, the men sent the rock careening to the sands below. The townsfolk were outraged, and demanded that Logan Rock be returned to its home atop the Cliffs Treen. Lieutenant Goldsmith was made to hire an engineer and a force of six men to hoist the boulder to its original position – where it still rocks to this day.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook