The Spirited Life and Sad End of the First Indian-American Children’s Book Author

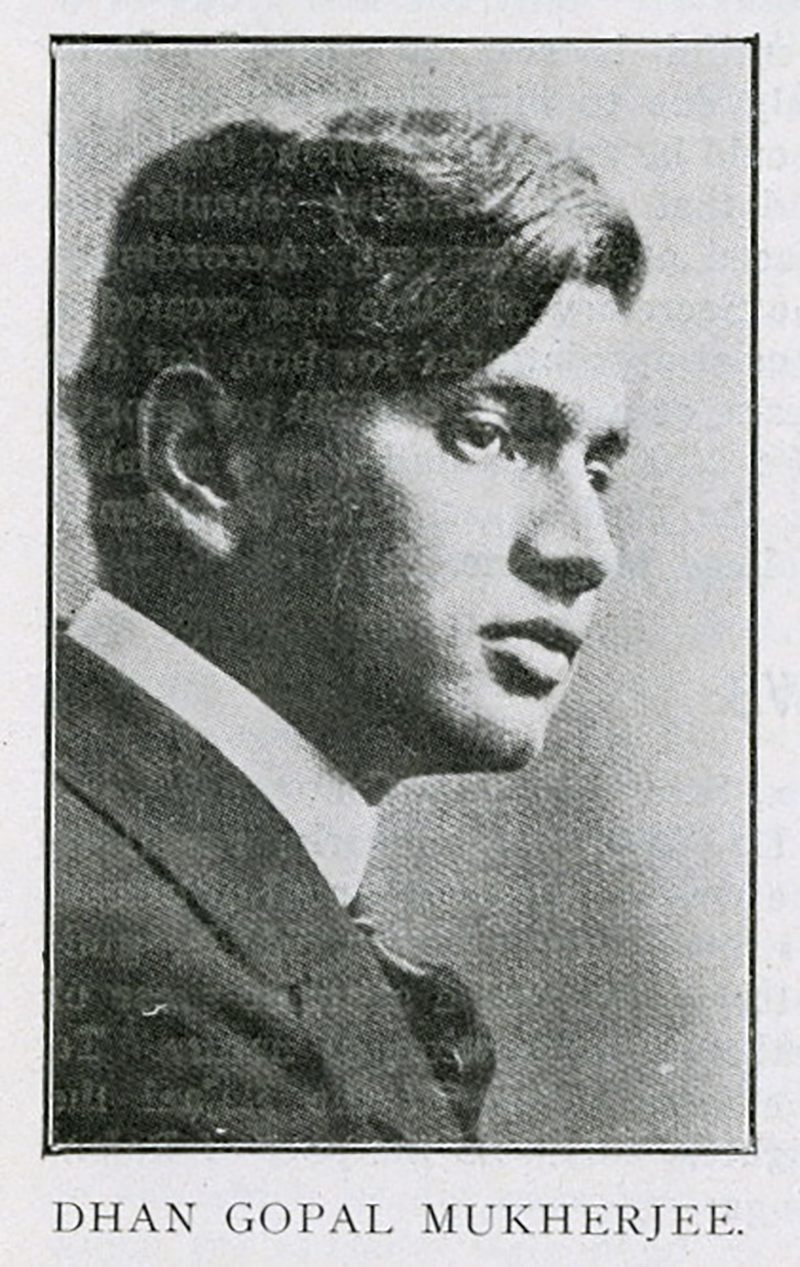

Dhan Gopal Mukerji was a prolific writer and an early cultural ambassador between East and West.

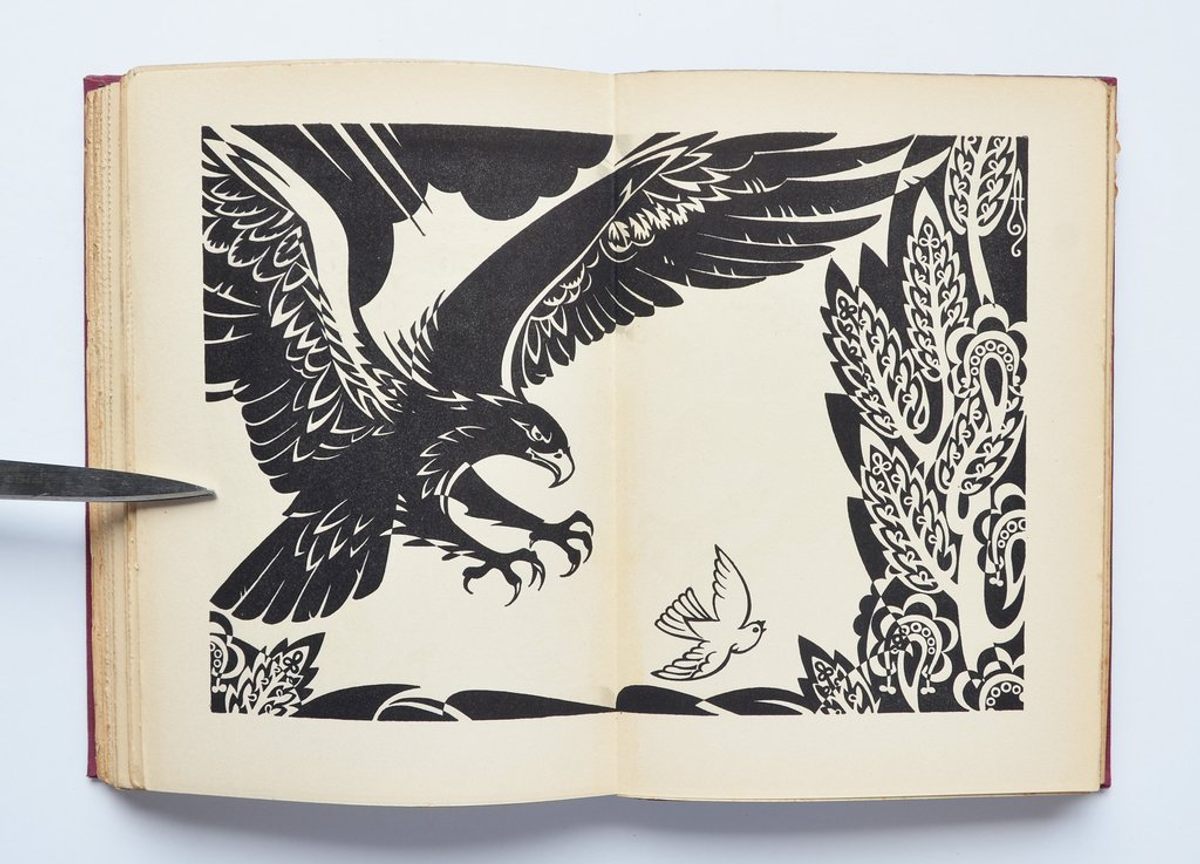

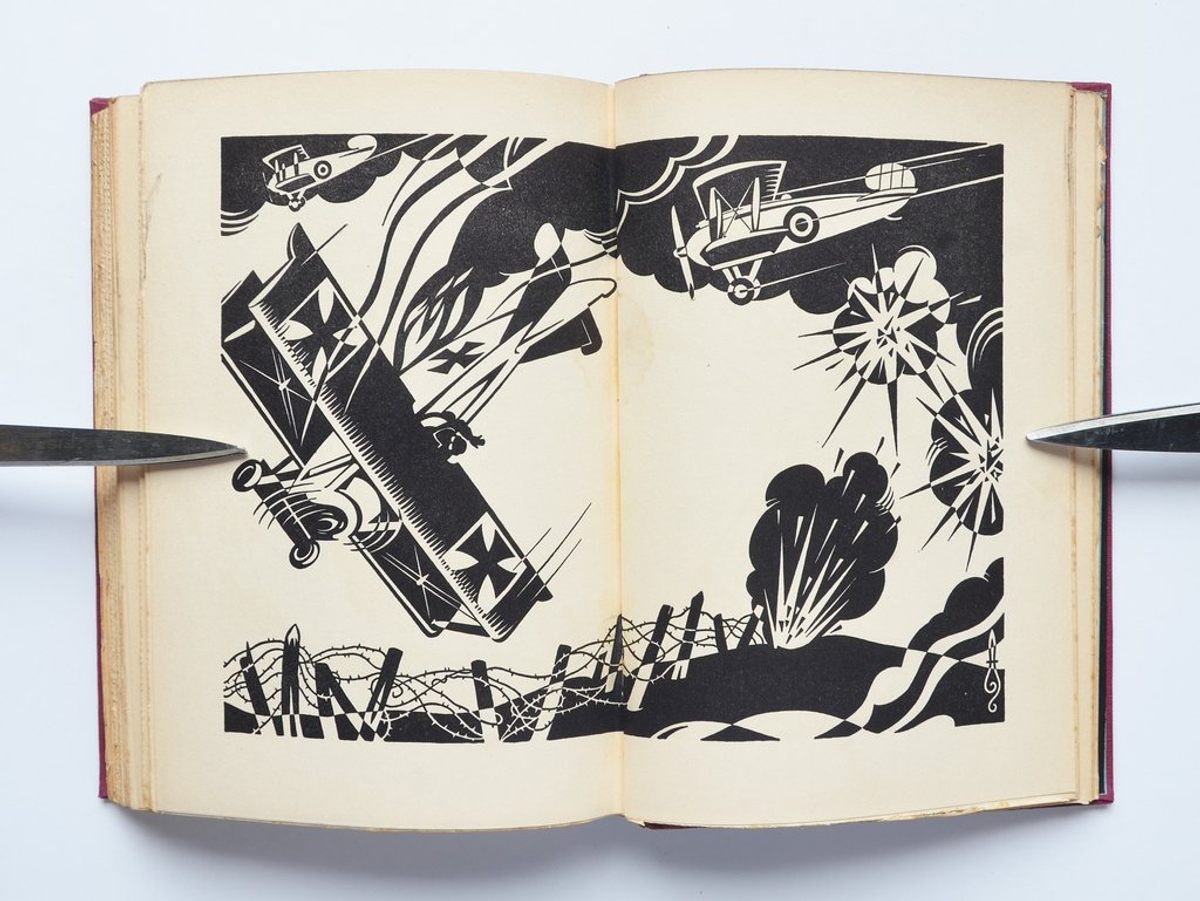

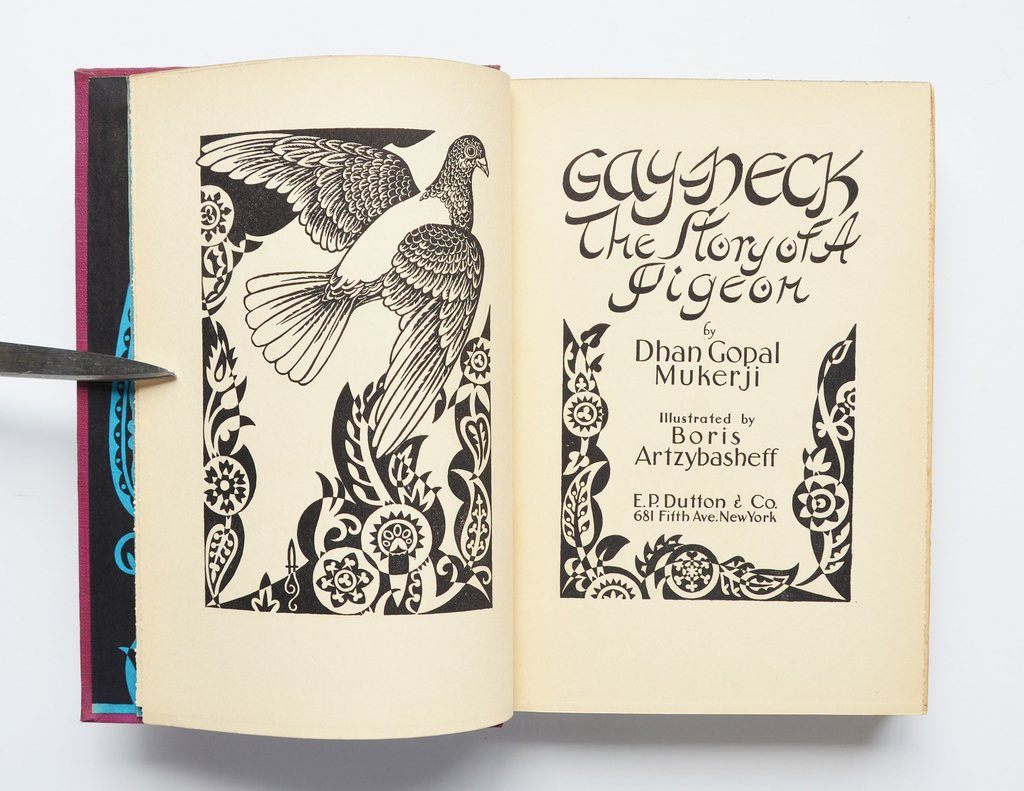

Gay-Neck, the Story of a Pigeon, is the tale of Chitragriva, or “Gay-Neck,” the most beautiful pigeon in Calcutta. Gay-Neck is born in a fancier’s flock and attentively watched and cared for by an unnamed narrator, who occasionally cedes the story to the bird. “It is not hard for us to understand him,” the narrator says, “if we use the grammar of fancy and the dictionary of the imagination.” Gay-Neck distinguishes himself from his flock with leadership, selflessness, and bravery before he is sent off to the front lines of World War I, where he serves as a homing pigeon, dodging German planes and struggling through clouds of mustard gas. The bird describes the clamor of war with a child’s innocence and a naturalist’s eye for detail:

Even there, in that very heart of pounding and shooting, where houses fell as birds’ nests in tempests, rats ran from hole to hole, mice stole cheese, and spiders spun webs to catch flies. They went on with the business of their life as if the slaughtering of men by their brothers were as negligible as the clouds that covered the sky.

In 1927, the Association for Library Service to Children gave Gay-Neck the Newbery Medal, its highest award for children’s literature. The book offers lessons of perseverance and sacrifice with the exotic detail of Rudyard Kipling, but without his colonial baggage. Gay-Neck was written by Dhan Gopal Mukerji, the first writer and scholar from the subcontinent to find success in America. In his time, Mukerji was a groundbreaking figure, a dashing, eloquent, astute observer of both the country of his birth and his adopted home. Over a relatively brief career, he gave countless talks about India and wrote poetry, drama, fiction, social commentary, and philosophy, in addition to the successful children’s books for which he is best known.

Despite his success, Mukerji was troubled by India’s political plight under the British, the elusiveness of spiritual communion, and a predisposition to loneliness and depression. The story of his spirited career and sad death has fallen into relative obscurity, though he primed America for later waves of South Asian immigrants and their descendants—including many a writer among them, from Jhumpa Lahiri to Bharati Mukherjee to Atul Gawande.

Dhan Gopal Mukerji was born near Calcutta to a high-caste family in 1890, one of eight children of an illiterate mother and an attorney father. His mother gave him fables, while his father introduced him to Don Quixote, taught him the six great Indian melodies, and told him of the Sepoy Rebellion. A sister with whom he was close died at age 12, but he has little to say about her passing in his unusual early-life memoir, Caste and Outcast. “In India we live with death on more intimate and friendly terms than in the West,” he wrote, “and it makes less impression on us.”

At 10 he went to study at a Scotch Presbyterian school. At 14 he trained to be a priest by renouncing his possessions and living as a wandering beggar for two years. “You cannot have poets if you do not have beggars,” he wrote. This, as one might expect, was a formative experience, though after that he lasted less than a year as a temple priest.

The details of Mukerji’s life at this point get fuzzy. There are competing stories from his autobiography, his family, and biographies prepared by his publisher, E.P. Dutton, according to Gordon Chang, a scholar at Stanford who wrote the introduction to a recent edition of Caste and Outcast. He worked in the textile industry and ended up in Japan. By one account, he’d dramatically escaped British authorities after the capture of his brother, a revolutionary. By another, he was in Japan to learn about the textile trade and recruit supporters for the Indian independence movement. In Caste and Outcast he chooses to voyage to the United States, but in another version he accepted a free meal in Yokohama, which indebted him to work as a contract laborer on a ship headed to San Francisco.

He was, he writes, instantly enamored of and disappointed with America. “No sooner did they see that I had such feelings for their country than they began to knock it out of me in a very unceremonious fashion,” he wrote.

He took odd jobs, as a dishwasher or housekeeper, and was typically fired for not knowing some basic skill, like serving soup or making a bed. In each case, however, he convinced his erstwhile employer to let him observe the task to ready him for the next job. He may have picked asparagus and hops and beets, often with the few fellow Indians he encountered. In 1910 he enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley—again, there is no consensus on how he ended up there—and later transferred to Stanford, where he earned his degree. At this point the stories about his life begin to align. He fell in with socialists and anarchists, and impressed his professors. The first president of Stanford, David Starr Jordan, became a lifelong supporter and friend.

At the time, most Americans knew little of India or Hinduism beyond what they read in Kipling or heard from returning missionaries. There were simply not many Indians in the United States. Immigration from Asia was heavily restricted, and Asians wouldn’t legally be allowed to become citizens until after World War II. Mukerji was the right mind and personality at the right time; he became something of a cultural ambassador for the East, first to American intellectuals, and later to the wider public, through both his writing and exhaustive speaking tours. He found America an inspiring and frustrating place: “I found it had its vulgarity, its bitter indifference, its colossal frauds. It has made just as many mistakes as India has in her time,” he wrote. “And yet there was something constructive in both of these civilizations.”

At Berkeley he met, and later married, Ethel Ray Dugan, an educator. They had a son, Dhan Gopal Jr., and moved to New York, where they were a vivacious social and intellectual presence. The 1923 publication of Caste and Outcast established Mukerji’s reputation. It’s a strange autobiography, cut through with grand, mythical speech that seems pulled from Indian fables, juxtaposed with voices of brusque American folksiness and pretentious anarchists. “At its heart, Caste and Outcast is an optimistic book, reflecting the author’s own joy in writing and in discovering his own purpose in life, which was to serve as what one might call a literary missionary,” writes Chang in the introduction. “The publication of Caste and Outcast marked a turning point in American’s understanding of India.”

In his relatively brief literary career, Mukerji published 25 books, including the children’s books for which he won the most popular acclaim. These books are distinguished by wisdom and courage and life lessons, and often feature animals such as Gay-Neck and Kari the Elephant because, Mukerji said, “Animals have young souls.” The publisher E.P. Dutton wrote, “In only a few years he has jumped into public favor—and more—he has won the hearts of America’s children.”

But success did not hang well on Mukerji. He struggled with depression and anxiety, traits he shared with another prominent friend, the man who would later become India’s first prime minister, Jawarhalal Nehru. “Both were restless, driven, sensitive, and inwardly tortured,” writes Chang.

“I have been so fragile. My nerves could not and will not stand any strain. I need one whole year of the Alps. It is an awful state to be in: I need silence and I can’t get it in America,” Mukerji told friends in a letter just before a nervous breakdown. He was also a distant, remote father. Gopal, as his son was called, wrote about his father while in high school at Exeter Academy, including his struggle with “The three greeds and terrors: desire for fame and fear of oblivion; desire for money and the fear of the lack of it; and last, the desire for all the little vanities of life, and the fear of not enjoying them.”

“Success is a curse, a stumbling block in the path of a spiritual life,” Gopal added. And a spiritual life is what the increasingly isolated and stressed Mukerji had sought, unsuccessfully. Following another breakdown, on July 14, 1936, Dugan returned to their New Milford, Connecticut, home and found Mukerji hanging by his neck in the closet. He left no note, but the last thing he wrote was a letter to the Ramakrishna monastery, long the focus of his spiritual life: “You ask me to write, after reflection. I find, I am prepared. My decision has been taken, on reflection. It has been decided: I am. Who decided, you know it. I am mere instrument.”

“How can we feel regret or sorrow?” Dugan later wrote of her husband’s death. “He has what he wanted—the only thing he wanted.”

There was something else that he wanted, at least in the years before his demons overtook him, and that was to have an impact on his adopted country, where he saw so much potential, and so much hazard. “He promoted Indian spirituality to address the void in America’s soul,” writes Chang. “He only wanted to help America see beyond itself.” But that peace and insight, reflected in the final words of Gay-Neck, eluded him.

Whatever we think and feel will colour what we say or do. He who fears, even unconsciously, or has his least little dream tainted with hate, will inevitably, sooner or later, translate these two qualities into his action. Therefore, my brothers, live courage, breathe courage and give courage. Think and feel love so that you will be able to pour out of yourselves peace and serenity as naturally as a flower gives forth fragrance. Peace be unto all!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook