Instead of Money, This Portuguese ‘Bank’ Safeguards 27,000 Handpainted Tiles

This collection of azulejos in Porto isn’t just for conservation and display—it’s also open for withdrawals.

Faced with growing threats to its architectural heritage, the Portuguese city of Porto made an unusual choice: It opened a bank.

The Banco de Materiais, or Bank of Materials, is home to tens of thousands of azulejos—the painted, glazed ceramic tiles that cover the exteriors of buildings across Portugal. In varying shades of blue, maroon, and honey gold, they often depict ornate floral patterns or simple geometric repetition. Sometimes, entire mosaics of intricately painted tiles display scenes from Portuguese history.

The city has been collecting lost and damaged azulejos for more than 25 years. Some were saved from the walls of decaying buildings before they were torn down. Others were stolen from façades but recovered by law enforcement. Over 27,000 of them ended up at the Bank.

In 2010, the city opened the Bank to the public. Visitors might assume it’s just another museum, but it’s also an important public works project. For every azulejo on display, the Bank has thousands of others carefully catalogued in wooden boxes. Entire mosaics are disassembled and stored in order. And as its name suggests, the publicly-funded bank isn’t just for conservation and display—it’s also open for withdrawals.

Building owners who are repairing a damaged façade can search the Bank for missing tiles. If the piece is found, the Bank will give it to the building owner free of charge along with expert advice, so they can perform a proper restoration using the original materials. If an exact match cannot be found, the Bank will help the building owner find a suitable reproduction.

“They all seek our help in advance,” says Paula Lage, a senior technician at the Bank. “This makes all the difference when what matters is minimizing the destruction of materials.”

Amid the challenges of Porto’s rapid redevelopment, ongoing housing shortage, and growth as a tourist destination, the Bank says that it has given away more than 14,000 tiles since 2010, helping developers restore 275 buildings. It has provided additional technical support for 1,300 more. In the process, the institution has helped to preserve the visual identity that makes Porto unique.

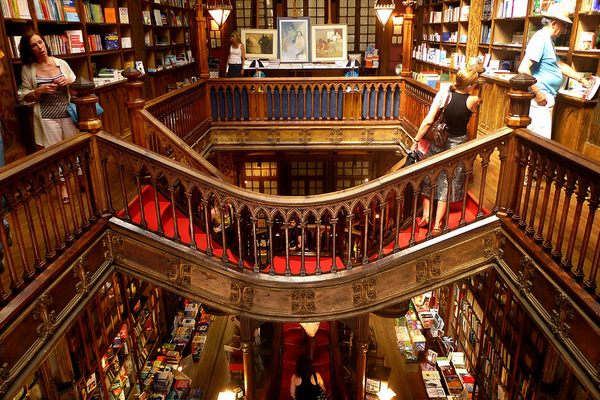

Porto’s impressive architecture runs the gamut from a Romaneseque cathedral to Rem Koolhaas’s Casa da Musica. But the look that defines the city is from a distinct period, says Luís Mariz Ferreira, a former academic who now works in architectural preservation. It’s why nearly half a million Instagram users have posted photos tagged with #azulejos.

“The image we have of Porto is the image of the 19th century,” he says. That’s when rapid industrialization and population growth first changed the look and feel of the city. It was also the height of popularity for azulejos, which had existed for centuries. During the 19th century building boom, the tiles covered everything from churches to coffee shops. But that growth stopped after the Second World War, when the Portuguese economy stagnated under an authoritarian regime.

Unfortunately, it was also a particularly bad time to stop maintaining tiles that had been installed a century earlier. The azulejos themselves were strong, but the mortars that held them—and even the buildings they were attached to—began to disintegrate. “The mortars were at the limits of their durability,” Mariz says.

At further issue was a government housing policy that kept rents low but neglected building maintenance. As 19th-century buildings crumbled, Porto’s residents moved to new developments on the outskirts of the city. “The main area of the city was very empty,” Mariz says. To make matters worse, some of the original tiles were stolen and sold to private collectors.

Porto’s trajectory shifted in the late 20th century. Democracy returned, Portugal entered the European Union, low-cost flights turned the city into a must-see vacation destination, and UNESCO declared Porto’s city center a World Heritage Site in 1996. Suddenly, azulejo-covered buildings were a draw, and tourism grew by 128 percent between 2010 and 2017.

At the same time, housing laws changed and investors—many from outside Portugal—began fixing up old buildings at a rapid clip. From 2013 to 2017, Porto’s city council issued 1,170 rehabilitation permits, which accounted for 72 percent of all construction in the city, according to AICCOPN, a construction industry association in Portugal.

In another twist of fate for the azulejos, the Bank of Materials started its work protecting tiles, cataloging artifacts, and studying and teaching traditional techniques just as redevelopment took off. If it hadn’t done so, Porto could have lost part of its unique architectural heritage to developers who valued a quick return on an investment more than the extra effort it took to conserve original materials.

“The Bank of Materials managed to turn a social problem—theft and degradation—into a cultural opportunity,” says Lage.

Mariz praises the Bank’s work, although he says that the vast scale of a tile-covered wall makes it hard to make repairs with authentic tiles. “They only give you the tiles if they match the pattern, the color, and the format,” he says. “The idea is brilliant of course, but the number of the pieces they have are very few.” Sure, an inventory of 27,000 vintage tiles may sound like a lot, but Mariz says it’s not uncommon for him to have to replace hundreds of tiles on a single job. When that happens, the Bank will connect a building owner with a company that makes reproductions.

“It’s sad, but the production of reproductions is increasing very much,” he says. In addition, rapid construction has led to a phenomenon known as façadism, through which developers demolish everything but the parts of a building that face the street, then rebuild the interior using modern methods. “We have the look of the old buildings, but there is new construction under the façade,” Mariz says. “The old city is nowadays very, very new.”

Even if it can’t save tiles that have been lost to time, Lage says the very existence of the Bank helps draw attention to the need for preservation of the tiles that still remain in place.

“The Bank of Materials space is an awareness space,” she says. According to Lage, building owners know they can reach out to the Bank if they want to perform a restoration, or if they own a building whose tiles are at risk.

The Bank also relies on cooperation among different departments in the city. For example, if a building is in danger of imminent collapse, the city’s fire department will use its equipment to secure important materials.

As newer tiles age, the Bank continues to work to preserve them in place so they don’t end up in its collection. “All tiles are important regardless of age,” Lage says. “They are testimony of different times and all marked in some way the history of the architectural heritage of the city.”

There’s plenty of work to do: AICCOPN estimates that 15.5 percent of buildings in Porto still need restoration, with an estimated price tag of $1.3 billion. A walk around the city reveals plenty of construction underway, but abandoned and crumbling buildings are still a common sight.

The Bank’s next steps include creating a preservation curriculum for local schools, and hosting workshops for developers and building owners who wish to carry out conservation or restoration work.

Despite the value of its preservation work, the Bank of Materials hasn’t yet become a major tourist attraction. While a million visitors check out Porto’s historic wine cellars each year, only around 12,000 people venture into the Bank’s building, just off the Praça de Carlos Alberto. Those who do, however, get a chance to witness a modern public works initiative in a city filled with history. They also get a glimpse behind that 19th-century façade.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook