The Strange Afterlife of a Mysterious Tomb Inscription

“I lay with another but I love you, the one most dear to me.”

The drama in Beit Guvrin-Maresha National Park in Israel is not apparent on the surface. It is down below. The park, approximately 120 acres, holds the excavated remains of two ancient cities—Beit Guvrin and Maresha—where much of life and death took place underground.

This fertile area in the Judean foothills, known as “The Land of a Thousand Caves,” consists of a thin crust of hard rock on top of a layer of soft chalk, which allows for easy excavation that attracted ancient settlers, who founded Maresha in the third century B.C. and Beit Guvrin in the third century A.D. Archaeological excavations of the site, which began around 1900 and expanded during the 1980s and 1990s, uncovered dozens of tunnel systems carved into the rock, spanning thousands of rooms and hundreds of features: quarries, cisterns, olive presses, columbaria, and burial caves. Both cities, shaped by the region’s ethnic mosaic and trade routes, were multicultural metropolises of their times. In 2014, the complex was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

All this is by way of introduction to a single cave, used for burials, and a single, mysterious inscription that has puzzled experts for more than a century.

One summer day in 1902, American theologian John Peters and German classical scholar Hermann Thiersch arrived at Tel Maresha (the mound that indicates the site of the ancient city). Aside from a short scientific excavation conducted there in 1900, the rocky hills had not given up very many of their secrets.

“It was early in June, 1902, when we heard in Jerusalem that there was much illicit excavating for antiquities in the neighborhood of (the Palestinian village) Beit Jibrin, and especially that in a tomb at that place some notable finds had recently been made, for which dealers had paid £50 on the spot,” the scholars wrote in their 1905 book, Painted Tombs in the Necropolis of Marissa. “We had been so often deceived, and induced to descend with exalted expectations into holes that proved to contain nothing of interest, that it was with some hesitation, the hour being then quite late, and only on our guide’s reiterated assurances of the real importance of this hole, that one of us descended into it. It proved to be the most remarkable tomb ever discovered in Palestine.”

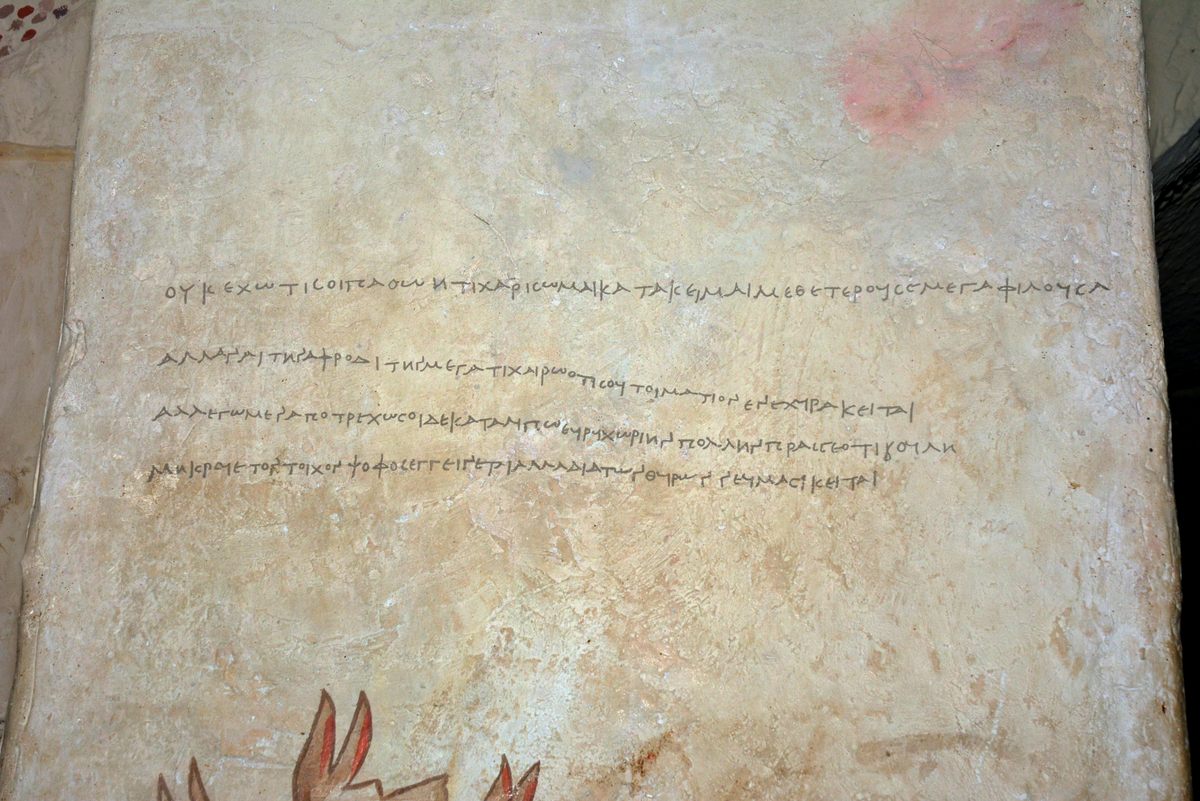

The cave consists of an entrance hall with burial alcoves extending from both sides. The dead were placed in these alcoves for about a year, until their bodies had decayed, before being moved for more permanent burial. Thirty inscriptions and five graffiti, all in Greek, were found in the tomb. Most of the inscriptions state the names of the departed, though some add a macabre touch: “This is also taken,” warns an inscription above one alcove, or “Do not disturb the girl.”

Animals and mythical figures from the Hellenistic world are painted over the alcoves, attesting to the cultures and influences that called the city home. When Peters and Thiersch arrived in the recently opened cave, some faces in the human figures had already been mutilated by local villagers, who regarded them as sacrilegious under Islamic law. “The heads which had been scratched out were effaced, so we were told, by the Sheikh of Beit Jibrin,” their book reads, “a pious Muslim, who, on entering the tombs, cried out ‘Haram,’ ‘forbidden.’”

“This is the only painted cave from the Hellenistic period in the land of Israel and its whereabouts, where you can see the influence of the Ptolemaic-Egyptian rule on Maresha during the third century B.C.,” says Adi Erlich, archaeologist and art historian from the University of Haifa.

Some of the animals painted in the cave, Erlich adds, tell us about the painters’ knowledge of the world at the time. “The griffin was considered a real animal, not just mythical,” she says. “The imagined giraffe looks like it does because its Greek name, camelopardalis, means ‘camel-leopard.’”

The cave was subsequently named the Sidonian Cave or Apollophanes Cave, since it was used by Apollophanes, the head of the city’s Sidonian community around that time. One of the inscriptions cave is dedicated to him: “Apollophanes, son of Sesmaios, thirty-three years chief of the Sidonians at Marise, reputed the best and most kin-loving of all those of his time; he died, having lived seventy-four years.”

But one inscription, above a painting of the mythical hound Cerberus, carries even more mystery:

There is nothing left I could do for you, or anything that will give you pleasure. I lay with another but I love you, the one most dear to me. In the name of Aphrodite, I am glad of one thing, that I have your coat for collateral. But I flee, and leave you to your freedom. Do as you will. Do not bang on the wall, the noise is heard inside. We will signal each other with movements. Let this be our signal.

In 1902, Peters and Thiersch thought the inscription was a sign of a secret tryst. It “is evidently erotic, and appears to give us a glimpse into an ancient romance,” they wrote. “A maiden has written on the door of the tomb a message to the lover whom alone she really loves, to arrange for further intercourse between them, which is henceforth possible only in the sign language of nods and becks … The spacious tomb, as yet quite or almost unused outside of the city, must have been a convenient rendezvous for lovers. Here in the twilight shadows they may have waited for one another on the benches, and while they waited, scribbled all sorts of signs on the wall.”

Not everyone is convinced. Some believe that it is indeed a message between two lovers, others that is more like a playful love poem. Others claim that the writer was a sex worker, sarcastically warning a client to come back and pay her.

“We will never reach a conclusion about which interpretation is the right one,” says Avner Ecker, a professor of classical archaeology at Bar Ilan University. “The inscription is highly ambivalent.” The scholars who edited the Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palastinae, a compendium of ancient inscriptions from the region, published in 2010, find it to be weird in several ways. They state that “almost everything in this text is uncertain: one or more authors, assignment of speakers, meter, a verse-number versus a line-number, and, of course, text and interpretation.”

The corpus references the late Mitchell Dahood, an American Jesuit and scholar of Semitic studies, who “uses the story of Judah and Tamar to establish the practice that a man might leave a pledge with a prostitute.” The Book of Amos “reveals that this pledge was often a cloak.” The suggestion is that the writer, stiffed by a customer, still had his coat, which he had left as collateral.

Chava Bracha Korzakova of Bar Ilan University claims that the inscription was not meant to be taken literally, but rather is a line from a song, “not an ad hoc inscription but a passage from a drama of a genre close to Greek New Comedy. The quote was inscribed by a person who had been waiting in an abandoned funeral cave for a tryst … The contents of the whole text concerned a hetaira’s [a sex worker in ancient Greece] ransom.”

“The prostitute-client interpretation was invented by men,” Ecker laughs. “Personally, I prefer the interpretation that divides the inscription between two speakers: a dead man and a living woman. He’s dead, she’s alive and has moved on. He grants her permission to go on with her life beyond the cave walls, and is glad that she kept his coat as a keepsake. The inscription is at the cave’s entrance, above the painting of Cerberus. Cerberus and the inscription symbolize the boundary between the world of the living and the world of the dead, between the dead lover and the living woman.”

Although Peters and Thiersch, as above, had been in favor of the “secret tryst” theory, the interpretation favored by Ecker is cited in their book as well, with their own translation, as another option:

(The dead man to his living lover): “I lie with another [Death], though loving thee greatly.”

(The woman to her dead lover): “But, by Aphrodite, of one thing I am very glad: that thy cloak remained as a pledge.”

(The dead man): “But I run away, and to thee I leave behind free room aplenty. Do what thou will.”

(The dead man continues): “Do not strike the wall: that does but make a noise. There is nothing more to do.”

Despite its antiquity, the inscription, interpreted this way, might echo much of the five stages of grief in the modern Kübler-Ross model, which dates to 1969: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. But its true meaning will surely remain a beautiful, puzzling, poetic, intimate mystery.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook