Why Is There Just One Top Banana?

The world is full of delicious alternatives, but most people have only tasted one kind.

This article is adapted from the August 28, 2021, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

I eat a banana just about every day. But for almost my entire life, I only ever ate one kind: the Cavendish. Originally from China, it’s the banana variety that conquered the world: the same color, taste, and shape nearly everywhere you go.

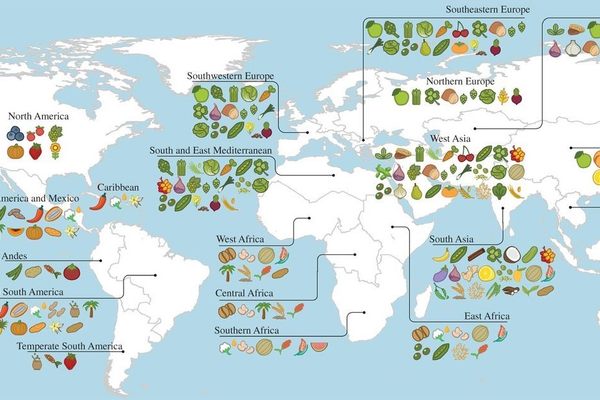

But in the banana’s ancestral homelands—Southeast Asia, India, various Pacific Islands—the fruit is found in endless varieties. They are yellow or red or blue. Some are thought best for snacking, others for sautéing, or even brewing beer. They grow long or squat or somewhere in between. Almost everywhere else, though, the only available banana is the yellow, milky Cavendish.

This contrast—in terms of fruit diversity in different regions—is not an anomaly. Growing up in New England, I chomped on dozens of apple varieties that are rarely found in regions too warm for orchards. And while I can only pick between Russet, red, or gold potatoes, Peruvians can choose from a full rainbow of distinct tubers.

Still, few crops epitomize the dominance of one variety, the triumph of the monocrop, quite like the banana. Here’s why we depend so much on the Cavendish, and what most of the world is missing out on.

The Second Bananas

How do you expand your banana horizons? Well, if you live in the U.S. or Canada, you can order a banana variety box from Miami Fruit, which grows and ships hard-to-find produce: everything from dragonfruit to foot-long avocados.

Two weeks ago, my box arrived. I gathered several coworkers in a Brooklyn park, then peeled, sliced, and sampled seven bananas that none of us had ever tried before.

Our first banana had the texture of an underripe Cavendish that still somehow had the sweetness and taste of a ripe one. “I’m indifferent,” a coworker declared. Subsequent bananas, though, made me yearn for weekly deliveries.

One was like a Cavendish whose flavor was concentrated into a smaller package. We groaned in delight at our first taste. “It’s all the banana I need,” a colleague crooned.

Another had notes of melon and pear, and a slight, complexifying tartness (“Delightful!”), while a third tasted custardy, like banana pudding.

A word of warning to other banana adventurers: It’s more challenging to tell when unfamiliar varieties are actually ripe. That’s how we ended up sampling a hard, chalky banana that made my boss’s children howl when they took the first bite. (A few days later, it tasted fine.)

When I got home, I peeled and ate a classic Cavendish. Everything was routine: the thickness of the peel, the texture, the taste. It was like a Starbucks coffee: comfortingly familiar, but absolutely inferior to many of the specialty options I’d just tried.

4 Reasons We Have Boring Bananas

1) It’s (kind of) our fault

It’s a truism of the produce industry that consumers want a consistent experience. It’s not just bananas: Many of us know only one kind of avocado, and if you show up at a grocery store to sell carrots, they’ll likely ask if they can all be the same kind, shape, size, and color.

2) Bananas are sexually sterile

Want to breed a better banana? Give up now. Commercial bananas have no seeds, and the trees’ gorgeous red flowers are not fertile. (Instead, bananas are cloned.) Wild bananas have seeds, but are hard and almost inedible.

3) The fruit of the people

In mid-1800s New York, eating a banana was a status symbol. Now, around the world, it’s often the cheapest fruit in the store. And that is the obstacle faced by any small farmer who dreams of selling better but expensive bananas.

4) The banana industrial complex

Turning a tropical fruit into a cheap, global commodity requires global infrastructure on a mass scale that is unique to bananas. From the refrigerated shipping containers to the hormones that delay ripening and an unimaginable number of just-the-right-size shipping boxes, everything is tailored to the Cavendish. Introducing another banana variety would be like adding wrong-sized gears into a huge, global machine.

Cavendish Kryptonite

Are you itching to taste greater banana diversity? There are two scenarios in which that might be possible.

The first is that the Cavendish could be replaced by another variety. The Achilles’ heel of monocrops is their vulnerability to disease or pests. Until the 1950s, plantations shipped Gros Michel bananas around the world. They switched to the Cavendish only because a fungus wiped out Gros Michel trees. Now, a new version of the same fungus is attacking the Cavendish, and banana breeders are seeking a replacement.

The other is that banana customers could learn to pay for quality. Agricultural centers such as the Tropical Education Research Center in Florida regularly conduct taste tests, survey customers about how much they’d pay for lesser known fruits or veggies, and work with small producers to set up new supply chains for finger limes and non-Hass avocados.

To support their work, I encourage you to be the demand that you want banana producers to supply: Place orders with farms such as Miami Fruit in South Florida (the center of American tropical fruit production), write to your grocer requesting more banana variety, and keep an eye out for the odd non-Cavendish for sale in the store.

Last week, at my local store, I spied and purchased a few red bananas. Their taste was not revelatory, but, hey, after eating thousands of Cavendishes, it sure was sweet to taste something different.

*This newsletter drew from Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World, by Dan Koeppel, and an interview with Trent Blare of the Tropical Research and Education Center.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook