These Are the Most Realistic Fish Ever Carved From Wood

The National Fish Decoy Association contest celebrates the best of the best.

Rod Osvold carved his first fish decoy when he was a just a “knee-high” child spearfishing for pike in the frozen waters of the Minnesota winter. These decoys—first employed by Native Americans—serve as a crafty means to lure real fish. With his decoy dangling in the water, young Osvold attracted meandering pike toward his spear.

For certain types of fishing, these decoys can be even more effective than live bait: Not only can they be brighter, but they can be tailored to mimic the fish most appetizing to pike. But Osvold and others spend more time carving and painting than strictly necessary. “It becomes fun, and you kinda get addicted,” he says.

Osvold knew that he was far from the only one obsessing over decoys, which have long been sold to people looking for a mantelpiece item rather than a fishing tool. So about 20 years ago, he started the National Fish Decoy Association (NFDA). His goal? To help this community of heritage artists find its footing on the Internet, or at least find each other. Now, each April, the NFDA’s carving contest showcases the creative spirit that drives these artists to keep working at a much higher level than hungry pike require.

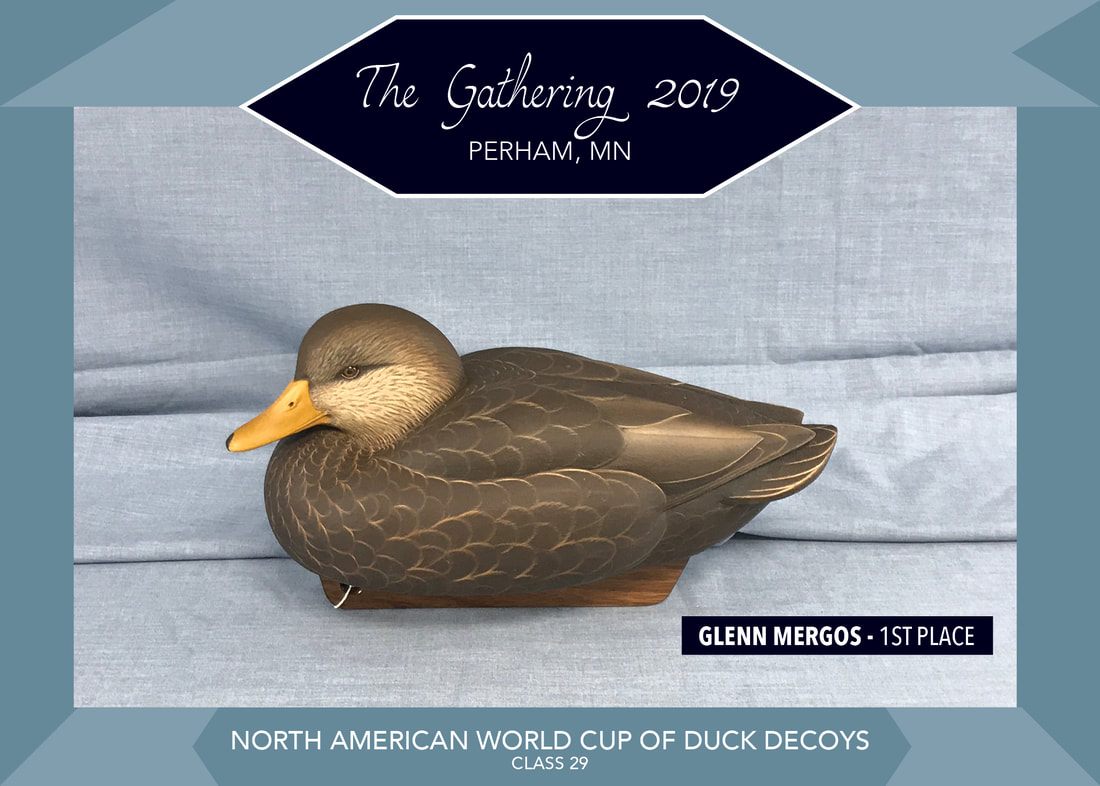

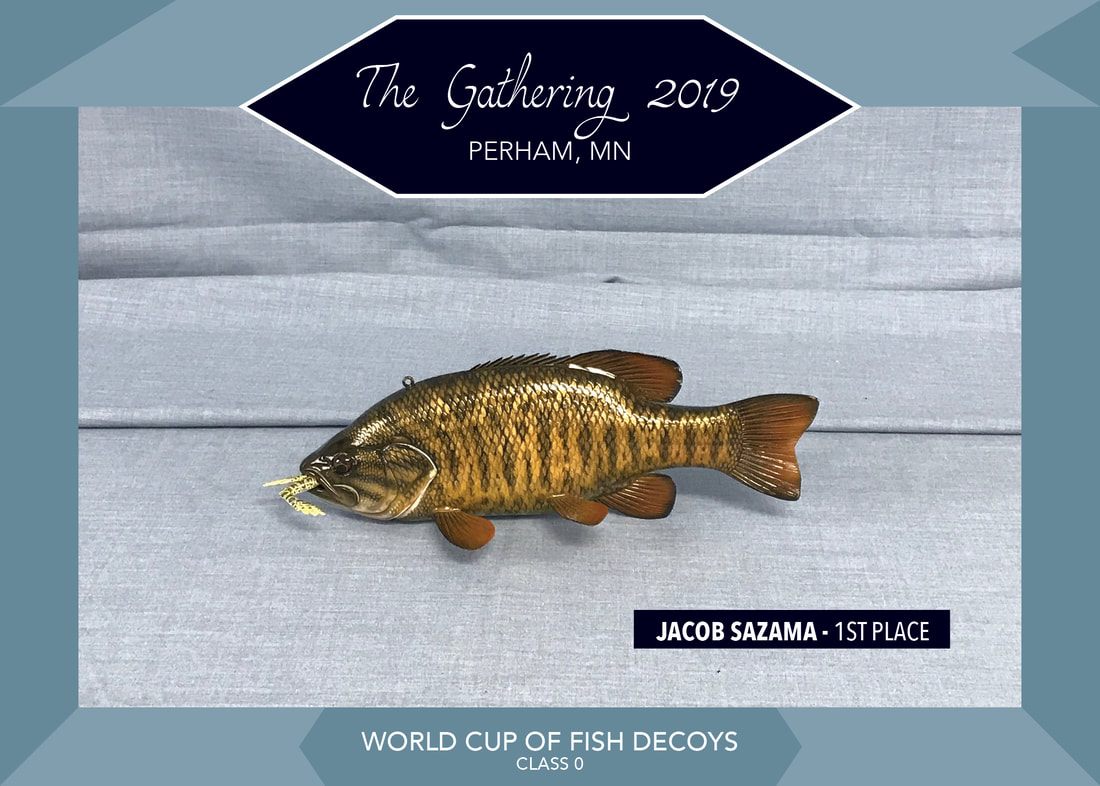

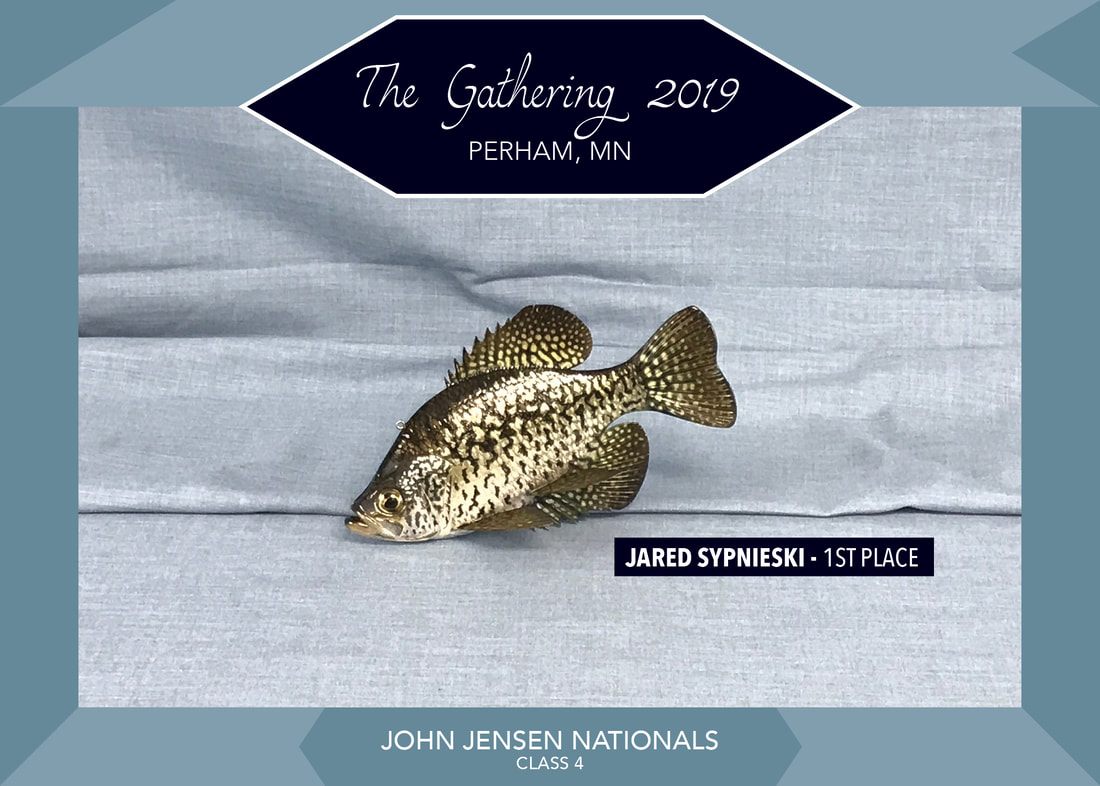

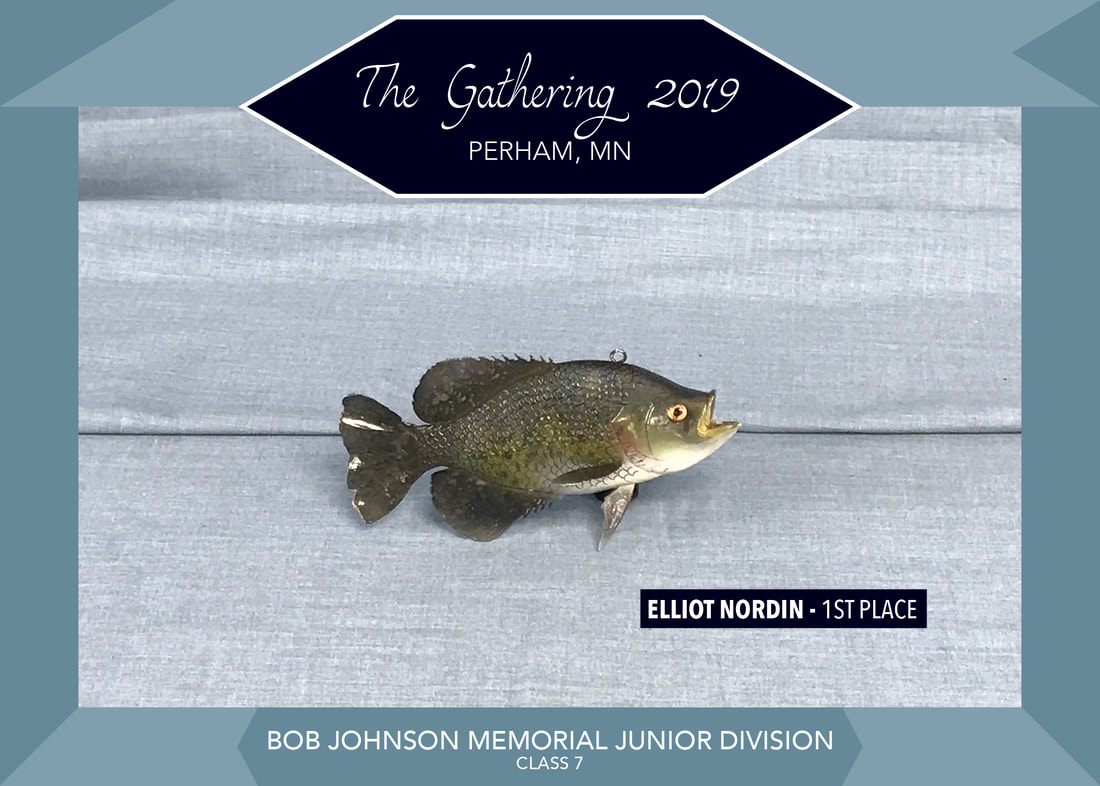

According to the NFDA’s website, the contest—held annually in Perham, Minnesota—typically receives about 400 entries. An elite few take home prizes across a variety of categories, which have expanded over the years to include birds and some other animals. (Duck decoys have long been popular with hunters hoping to draw ducks to seemingly safe areas.)

The award-winning works are so painstaking in their details, says Osvold, that this class of carvers can only realistically produce between 10 and 20 pieces per year. First, of course, there’s the actual carving—usually from cedar, tupelo, or white pine—that requires attention to every last scale, to the curves in each gill. Next comes the painting, which requires a small airbrush to tickle each of those tiny speckles and which takes, according to Osvold, 10 times as long as the carving. These high-end works are so refined that contest judging often comes down to the most minute considerations: The difference between first and second place, says Osvold, can be “just a little more dent in the cheek of a trout.”

Such hard work is, of course, a hard sell to the uninitiated, and Osvold concedes that the craft is losing traction with younger generations. He worries about the NFDA’s long-term prospects, but not about the current state of the art. Troy Helget’s Siamese fighting fish, pictured in this article, demonstrates the precision of these carvings. Helget’s fish won a first-place prize this year, and Osvold calls it the most impressive piece he’s ever seen.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook