The Low Down on the Greatest Dictionary Collection in the World

From “unabridged” to “slanguage,” Madeline Kripke’s library is a logophile’s heaven (or hell).

Madeline Kripke’s first dictionary was a copy of Webster’s Collegiate that her parents gave her when she was a fifth grader in Omaha in the early 1950s. By the time of her death in 2020, at age 76, she had amassed a collection of dictionaries that occupied every flat surface of her two-bedroom Manhattan apartment—and overflowed into several warehouse spaces. Many believe that this chaotic, personal library is the world’s largest compendium of words and their usage.

“We don’t really know how many books it is,” says Michael Adams, a lexicographer and chair of the English department at Indiana University Bloomington. More than 1,500 boxes, with vague labels such as “Kripke documents” or “Kripke: 17 books,” arrived at the school’s Lilly Library on two tractor-trailers in late 2021. The delivery was accompanied by a nearly 2,000-page catalog detailing some 6,000 volumes. But that’s only a fraction of the total. In summer 2023, the library hired a group of students to simply open each box and list its contents. By the fall, their count stood at about 9,700. “And they’ve got a long way to go,” says Adams. “20,000 sounds like a pretty good estimate.”

It will take years to fully process a collection of that size, but Adams just can’t wait. So he’s unpacking Kripke’s trove and sharing it online, the same way the women he considers a friend built it, one book at a time. “I go into the room where all of the boxes are and I open up a box and pull something out,” Adams says. He might find a rare and valuable Latin dictionary from 1502, or some edition of Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (the collection might have every printing of every edition)—but that’s not really what he’s hunting for. He’s looking for treasures like Kripke’s “slang wall.”

“This is my favorite wall,” Madeline Kripke told Narratively reporter Daniel Kreiger when he visited her West Village apartment in 2013. She shined a flashlight on glass-fronted shelves jammed with dictionaries full of the slanguage and cryptolect of small and likely overlooked communities. Kreiger listed some of the groups represented at that time, among them cowboys and flappers, mariners and gamblers, soldiers, circus workers, and thieves.

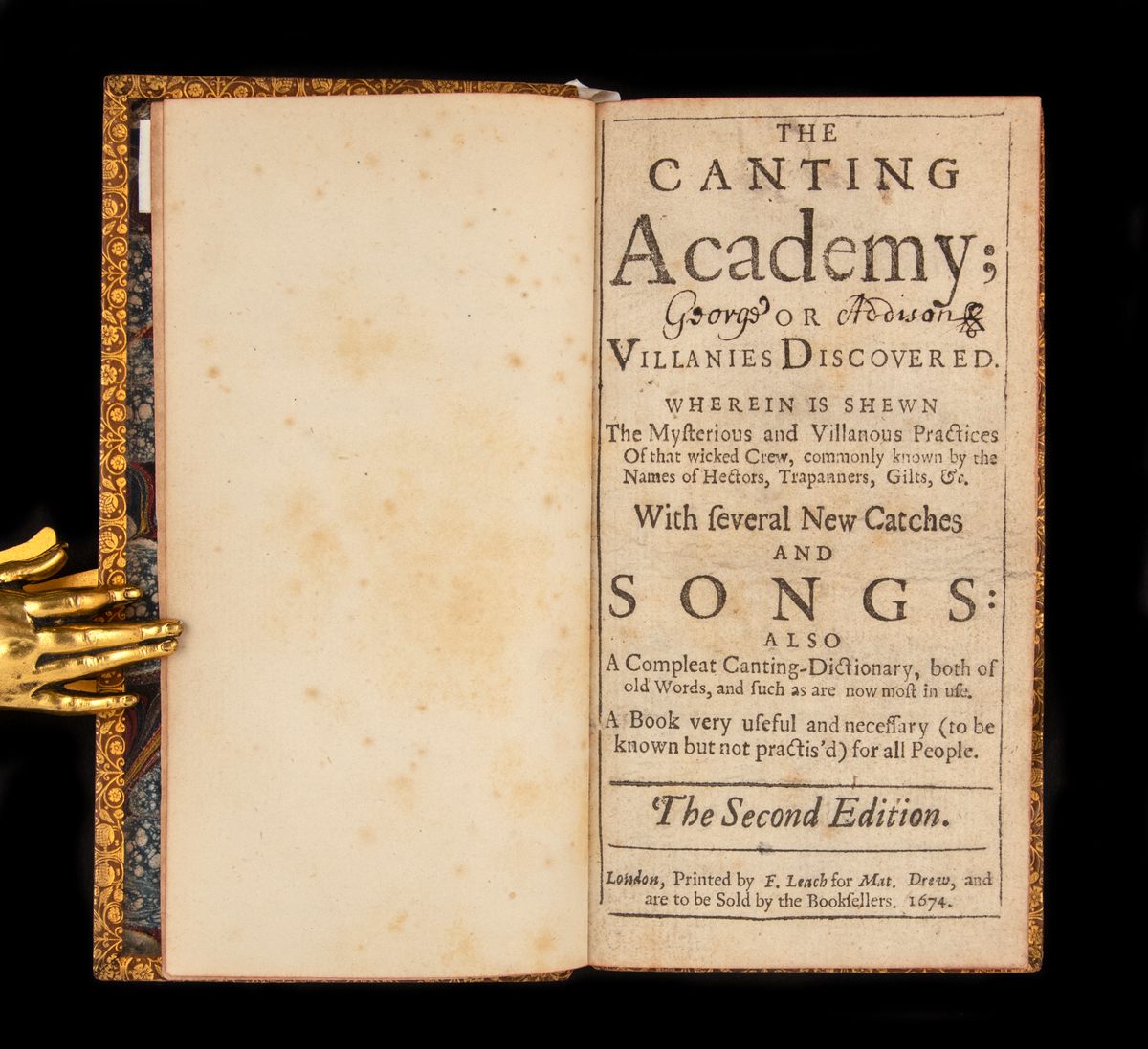

Among the first tomes Adams pulled from the boxes was a well-known example of the slang genre: The Canting Academy. This 17th-century dictionary by Richard Head is a guide to “cant,” the jargon of London’s criminal class or, as the subtitle to the second edition puts it, “The Mysterious and Villainous Practices Of that wicked Crew, commonly known by the Names of Hectors, Treppaners, Gults, &c.” (Adams wonders if a first edition is also hidden in the banker’s boxes.) With The Canting Academy, one can learn to translate the cant of the “priggs” (“all sorts of thieves”) to English: “lour” to “money,” “pannam” to “bread,” “lage” to “water.” Most of the language is indecipherable without this key, but Adams notes some usages that are common today. “To plant” something is, in centuries-old cant or modern-day English, “to lay, place, or hide.”

For Adams, Kripke’s copy of The Canting Academy tells a second story. It is also a record of many of its owners over the last several hundred years, among them an otherwise unidentified person named George Addison, turn-of-the-20th-century literary journalist Charles Whibley, and 20th-century book collector John Brett-Smith, from whose estate Kripke bought the book for £1800 in 2005 (about $4,000 in today’s dollars). It hides a hidden history of bibliophiles.

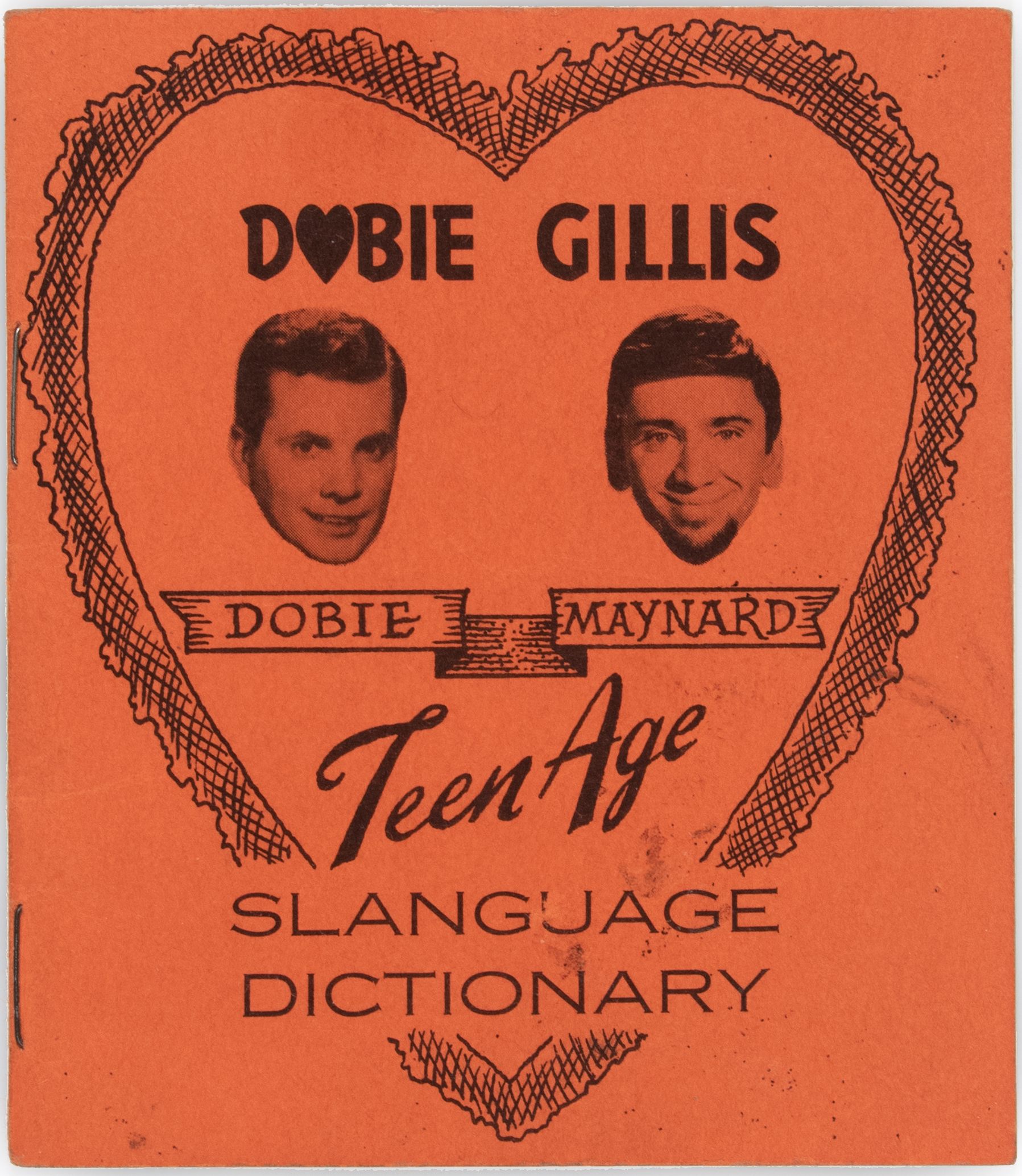

Much of what Adams has unpacked has a far less storied (and pricey) past, but, he says, the quirky and unexpected volumes in Kripke’s collection might be the most valuable to future lexicographers and historians. A bright red pamphlet with a doodle of heart on the cover might seem disposable, but it is an artifact of a particular place and time, Adams says. “Dictionaries are made by people, so they’re not just language books,” he says, “they’re culture books.”

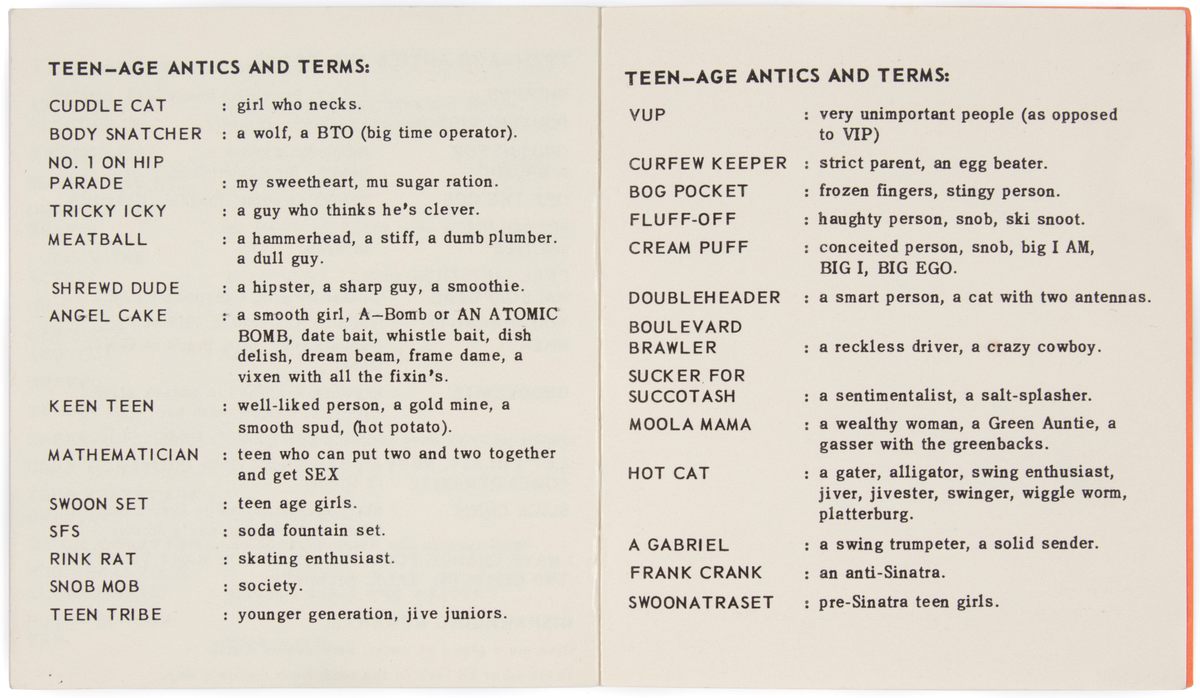

Printed in 1962 as a marketing tool for a CBS sitcom, that slim pamphlet featuring a big heart around the faces of two 20-something actors is Dobie Gillis: Teenage Slanguage Dictionary, filled with “teen-age antics and terms.” It’s the type of thing that might have been stuffed into a cereal box or inserted in a teen magazine, says Adams. “I’m pretty sure that most people threw the copy they had away, and so this one is a fairly rare item that says something important about the representation of teen language and culture in the 1950s and 1960s.” Thanks to Kripke’s copy we know that this, at least according to the marketers behind The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, was the era of the “keen teen” (“well-liked person”), the “cream puff” (“conceited person”), the “meatball” (“a dull guy”), and the “mathematician” (“teen who can put two and two together and get SEX”).

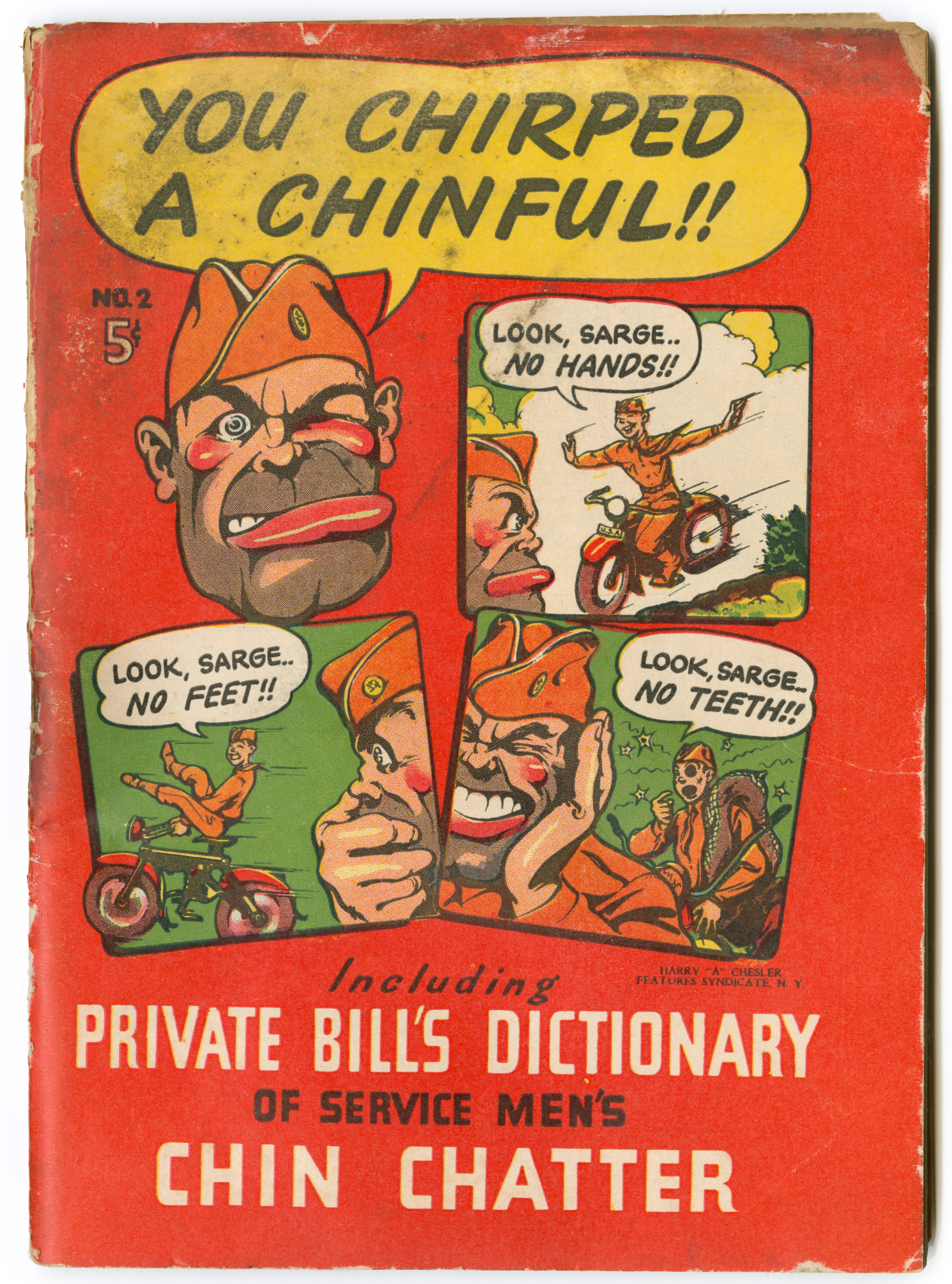

From another box, Adams unearthed a copy of You Chirped a Chinful!!, with an unlovely caricature of a World War II army sergeant on the cover. The comic book looks like a joke, and it is, but it also expressed a serious purpose. In the preface of the 1943 publication, the author writes, “During every historical crisis in the life of a country—many things are inevitably reborn.… One element rarely thought of in conjunction with the upheaval—is the birth of language.”

Crediting—or, perhaps, blaming—the U.S. armed forces for “thousands of slang expressions that have become part and parcel of our everyday lives,” the 64-page book catalogs the that language: for instance, a “cowboy” who’s always “behind the eight ball” talking to his “bunkie” about getting “dogged up” and “dragging.” That is, a tank driver who’s always broke talking to his pal about getting dressed up and taking a girl to a dance. Adams notes there’s also a lot of other, unpleasant words for women in the book, too. “Slang like that found in You Chirped a Chinful!! is ugly in hindsight, however acceptable it may have seemed in the 1940s,” he writes in the library’s blog, “and I doubt very much that it was acceptable to all even then.”

Kripke—“the mistress of slang,” in the words of one colleague—dedicated decades of her life to curating this collection of words, including countless ones we might like to forget. When she passed away without a will, the fate of her overwhelming library, plus a trove of documents on the history of dictionary making, was uncertain. Auctioning it off in lots could have brought the highest bids, but Kripke’s family worked in conjunction with the lexicographic community to preserve what Adams calls “her legacy.” That it was ultimately purchased in total by Indiana University Bloomington, a state university that committed to making the works accessible to the public, seems in keeping with the way Kripke herself viewed the collection, as a resource for the curious.

“You would go to see her in her Village apartment, and it was filled from top to bottom and side to side with books,” Adams says. It would have taken some digging but, “she would have the book that you need to see out for you and always some other specimens, too.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook