The Africans Who Called Tudor England Home

Hundreds of Africans lived freely during the reign of Henrys VII and VIII.

No monarchy in the history of the Kingdom of England has garnered a cult following quite like the Tudors (1485-1603). The betrayals, wars, and religious reforms of the Tudor dynasty have been depicted in numerous films and in the Showtime series, The Tudors.

One perception that we get from these pop culture portrayals of the lustful King Henry VIII and the tumultuous life of Bloody Mary is that Tudor England lacked ethnic diversity.

At the College of Arms in London on a 60-foot-long vellum manuscript sits an image of a man atop a horse, with a trumpet in hand and a turban around his head. This is John Blanke, a black African trumpeter who lived under the Tudors. The manuscript was originally used to announce the Westminster Tournament in celebration of the 1511 birth of Henry, Duke of Cornwall, Henry VIII’s son. Blanke was hired for the court by Henry VII. The job came with high wages, room and board, clothing, and was considered the highest possible position a musician could obtain in Tudor England.

Blanke was no anomaly, but was one of hundreds of West and Northern Africans living freely and working in England during the Tudor dynasty. Many came via Portuguese trading vessels that had enslaved Africans onboard, others came with merchants or from captured Spanish vessels. However once in England, Africans worked and lived like other English citizens, were able to testify in court, and climbed the social hierarchy of their time. A few of their stories are now captured in the book, Black Tudors by author and historian Miranda Kaufmann.

Pulling from exchequer papers, parish records, letters, and petitions, Kaufmann pieces together the lives of 10 Africans living in Tudor England. She sets out to change the way we understand Tudor life, Medieval England, and dispel the notion that the first Africans arrived in England as slaves. “Once people learn of the presence of Africans in Tudor England, they often assume their experience was one of enslavement and racial discrimination,” Kaufmann writes in her opening introduction.

The idea that Africans were mistreated by the English well before the Atlantic slave trade comes from a Queen Elizabeth I letter sent to the Privy Council in 1596, a sort of board of directors for England. In the letter Queen Elizabeth I largely blamed the African population for England’s ongoing social issues, writing that the country did not need “divers blackmoores brought into this realme.” This proclamation was sent to the mayors of England’s major cities. She later arranged for a merchant named Casper van Senden to deport Africans from England.

However, this edict wasn’t what it appeared. Kaufmann writes that van Senden originally approached the queen telling her that Africans were taking jobs away from English citizens, a problem that could be readily solved by paying him to deport them. “In the queen’s understanding, everyone she cared about would profit: there would be more work for good English folk who would then complain less to the queen, and a grateful merchant would make money from her kind deal. But like several other of Elizabeth’s schemes, they solved a problem that nobody really saw or worried about,” says Janice Liedl, Professor of History at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario.

There was one caveat in the proclamation: as Kaufmann notes, deportation was based on the consent of their masters, which in this case was likely in the context of an apprenticeship. In 1569 an English court ruled that “England has too pure an air for slaves to breathe in,” setting the first legal precedent barring slavery from England. This was so well known that according to Kaufmann the idea of England as a free land reached slaves working in Mexican silver mines. Juan Gelofe, a 40-year-old West African slave working in the mines around 1572 told an English sailor by the name of William Collins that England, “must be a good country as there are no slaves there.” The merchants thus refused to comply with the edict, unwilling to lose their African apprentices. This prompted van Senden to plead with the council to expand his authority over the situation. A second letter went out from the queen, but it too was largely unsuccessful and ignored.

While the African population in England would have been relatively small, possibly a little more than 300 individuals according to Kaufmann, they were respected members of Tudor society. In Black Tudors the importance of the church is discussed at great length. Through her research, Kaufmann uncovered evidence that Africans were married and baptized by the Church of England. More than 60 Africans were baptized in England between 1500 and 1640, along with hundreds of burials. “The church was the central social and cultural institution. Your membership in the church helped cement you as a legal person—if you became poor, sick or were injured, your parish had an obligation to take care of you,” says Liedl. The church gained further importance after King Henry VIII’s reformation where you could be tried as a heretic for not attending church, according to Liedl.

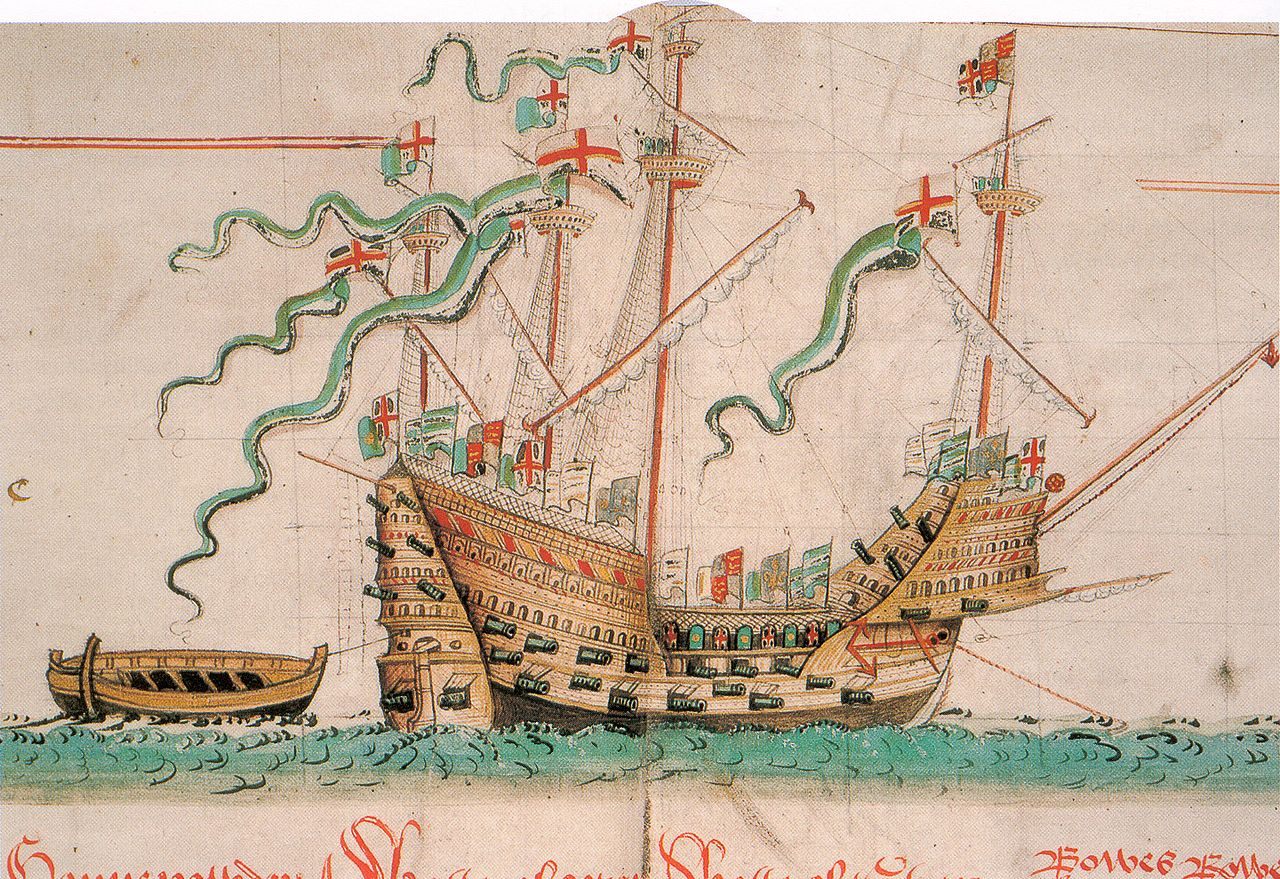

As Black Tudors details, Africans weren’t just members of society but were present during some of the major events of the Tudor era. Jacques Francis, a salvage diver from Guinea in West Africa, worked the wreck of the Mary Rose and Diego the circumnavigator explored the globe with Francis Drake. The aforementioned John Blanke would have certainly enjoyed some celebrity during his time due to his position in the royal court. He even performed at Henry VIII’s coronation and married a London woman. So, what changed? What prompted England to become a key nation in promulgating the Atlantic slave trade?

English expansion and colonization is often seen as the driving factor. In the 1640s the Dutch introduced sugar cane to the island of Barbados, showing Bajan planters how to cultivate the crop and providing them with African slaves as labor. Sugar dominated agriculture on the island, the English relied heavily on convict labor, but it was far scarcer than slaves. Taking their cues from the Dutch and to increase profits, the English began the triangular trade of African slaves to the Caribbean. But there was another factor, the transformation from the concept of slavery holding the generic meaning of another person owning another, to one defined by ethnic identities says Liedl. She explains that defining “white” and “black” in English literature comes from this decision toward the end of the Tudor period. The idea of racial superiority wasn’t a common theme in Tudor England. “As more black people were enslaved, Europeans began to write of black people as naturally slaves or as benefiting from slavery. These benefits included Christianity and civilization, both of which black Africans were assumed to lack,” says Leidl.

Black Tudors adds insight into a portion of English history that’s been overlooked as much as it’s been romanticized. It helps break down the preconceived ideas we have of England under the Tudors as a monolithic society lacking diversity. As Leidl explains: “As long as we think of England as naturally white and Anglo-Saxon, a pure state of people who have a set identity going back to antiquity that really didn’t change until the 20th century, we’re getting it wrong.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook