A Photographer’s Pursuit of the Elusive Black Panther

The challenge of capturing something almost impossible to see.

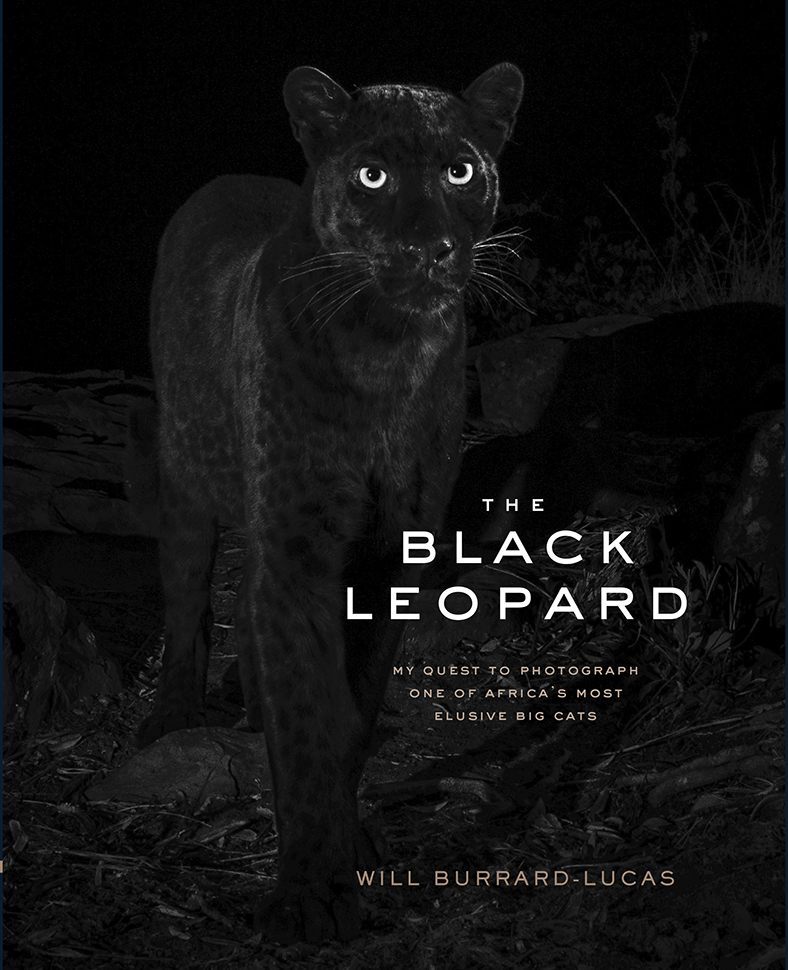

This story is excerpted and adapted from Will Burrard-Lucas’s The Black Leopard: My Quest to Photograph One of Africa’s Most Elusive Big Cats, published in March 2021 by Chronicle Books.

I set off at 5.30 a.m., aiming to get through the center of Nairobi before the terrible rush hour traffic could build up. Ahead of me was a four-hour drive to the town of Nanyuki, at the foot of Mount Kenya, and then another two hours onwards to Laikipia Wilderness Camp. For the first part I could use Google Maps to guide me, but once I left the tarmac I would be following written directions that seemed worryingly brief. I was half expecting to find myself lost somewhere in the vast Laikipia Plateau. As a precaution, I stocked up on water and biscuits just in case.

As the miles ticked by, my mind dwelled on the task ahead of me. Just what did I think I was doing? Did I really expect to get a photograph of a single, special leopard that the guides at Laikipia Wilderness Camp had only caught glimpses of on a handful of occasions over the past few years? The more I thought about it, the less hopeful I became. Surely this was going to be a monumental waste of time and effort.

But just imagine if I got a shot! An animal as rare, elusive, and iconic as a black panther—and in Africa, where they are so rarely seen and almost never photographed. I was right to try, even if my chances of success were close to zero. (A black panther is any large melanistic cat. In practice, among the species of big cat only leopards and jaguars have been observed in melanistic form. All black leopards are black panthers, and I use the two terms interchangeably.)

At the very least, this could be a worthwhile reconnaissance trip; I could speak to those who had seen the leopard, to get a rough idea of where its territory might be. In addition to my high-quality camera traps, I had with me 10 small trail cameras of the type used by researchers, and I could maybe spend the next six months moving them around to establish if the leopard was still in the area. Even getting a low-quality trail camera image would be pretty exciting.

I reached Nanyuki and, after pavement gave way to dirt, I passed through a couple of small villages before being immersed in the wilderness. Soon I was seeing wildlife: reticulated giraffes, gerenuks (skinny, longnecked antelope, well-adapted to arid environments), Grévy’s zebras (larger than regular zebras and with stripes so closely spaced that, from a distance, they appear to be a single shade of grey), impalas, and elephants. The landscape was becoming more and more rugged and beautiful. The road dropped down a steep rocky escarpment and I thought to myself what a perfect leopard habitat this was: lots of crevices to hide in and plenty of cover from which to stalk prey such as hyrax (stocky little mammals that resemble marmots but are actually more closely related to elephants) and klipspringers (small antelopes most at home in steep, rocky terrain). Looking up at one particularly craggy granitic outcrop with Dracaena trees poking out from the crevices, I couldn’t have imagined a more fitting lair for the elusive black panther.

I found my way to camp without difficulty and met the three guides: Steve Carey, the camp owner with whom I had exchanged emails; Stephen Leshorono, an experienced guide from the area; and Jasper Maberly, an assistant guide from the United Kingdom. It wasn’t long before we were talking panthers. Maberly had been guiding at Laikipia Wilderness Camp for a couple of years and had never seen the cat. Leshorono reckoned he saw a black leopard approximately once or twice a year on average, most recently down by the river. He didn’t know if it was the same individual each time or if there were several in the area. Carey told me he had seen black leopards in a couple of different places over the 10 years he had been there. Recently some cattle herders had seen a big male up on the edge of the escarpment. It seemed there might be a few around. But, if that was the case, how was it possible that nobody had captured high-quality images of one before? Was it really possible that I was the first wildlife photographer to attempt to document them in this location? Or was it simply that even though the cats are out there, they are just so elusive that photographing them is next to impossible? I suspected it might be both.

Then Carey told me that his neighbor, Luisa Ancilotto, had been seeing one quite regularly in the area around her house, and he reckoned that was probably the best place for me to start. He had made a plan for us to visit her.

The next morning Carey and I set off after breakfast. Ancilotto’s house was nestled halfway up an escarpment. The final ascent was so steep that the heavy Land Cruiser needed to be put into low gear to get up. Carey noticed footprints coming down the middle of the road. We got out of the vehicle and he proclaimed them fresh leopard tracks. We followed the spoor to where it left the road. The vegetation was dry and pale, so in theory a black animal would have stuck out like a sore thumb, but we couldn’t see anything.

We then followed the tracks back up the road and found where they emerged from the undergrowth. The leopard had walked along a well-worn animal path that led up from a gully, where it was likely there would be a freshwater spring. We agreed this path would be an excellent spot for a camera trap, but first continued on to meet Ancilotto.

She lives in a beautiful house with spectacular views out over Laikipia. On clear days, Mount Kenya is visible in the distance. As we stepped out onto her verandah, we soaked up the vista and spotted elephants and giraffes browsing far below. Her dogs, Bailey, a chocolate Labrador, and Kesha, a black Labrador-ridgeback cross, vied for our attention.

Ancilotto, a warm woman of Italian descent, had grown up in this area. Her father had founded a safari camp not far away. As we spoke, she seamlessly switched between English and Swahili, and briefly stepped away to field a phone call in Italian. She introduced us to Mohammed, a handsome Maasai man who worked as her chief askari (security guard), and then told us how they had first spotted the black leopard together around 18 months before.

The two of them had been driving back to the house after taking the dogs for a walk down by the river. Just as they reached the start of the steep slope, they spotted a black animal off to one side. At first, they thought it must be a dog. They were concerned—it was no place for a pet to be wandering around on its own, given the number of leopards in the area. Then they noticed a spotty leopard and it seemed that the black animal was following it. At that moment they realized it was a mother leopard with a black cub. Over the years they had heard stories of black leopards in Laikipia, but this was the first time either of them had ever seen one.

The mother leopard’s territory was roughly centered around Ancilotto’s house, and they had several more sightings of the black cub, and watched as it grew. It was probably a male, but they couldn’t be sure as it was still quite small. He was now around two years old and they thought he was still in the area. For a photographer who had been fascinated by melanistic cats for years, this sounded too good to be true.

Carey commented that at around this age, the cub would normally be pushed out of his mother’s territory by an older, stronger male wanting to mate with the mother. My excitement turned to nervousness. Was I too late? If he were to shift territory, our chances of finding him again in this expansive wilderness were extremely slim. I felt tantalizingly close, but I could also feel this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity slipping from my grasp. I needed to get the cameras deployed as soon as possible.

Ancilotto next introduced us to Ambrose Letoluai, an enthusiastic young Samburu leopard researcher who was conducting fieldwork for the San Diego Zoo. The zoo had a leopard research and conservation program in Laikipia, led by a biologist from the United States named Nick Pilford.

A year earlier, Letoluai and Pilford had caught wind of the black leopard sightings. They had reached out to Ancilotto and asked if they could set up some of their research cameras for their scientific study. Over the course of a year, the scientists had managed to capture videos of the black leopard, which Letoluai showed me on his tablet. It was a stunning creature. Best of all, the most recent footage had been captured within the last month.

Letoluai and Pilford had been compiling a scientific paper about the existence of this black leopard. They were very excited about it because the last mention of an African black leopard in a scientific publication was a record from Ethiopia in 1909. They were going to publish their findings in a month’s time and had a couple of requests for me. First, if I was able to capture images of the black leopard, they asked me not to publicize my photos until they released their findings. Second, while they had their own video footage of the leopard from their trail cameras, if I was able to get some high-quality stills, they wondered if they might use some of them to illustrate their release. I was happy to oblige with both requests. Of course, at this stage it was all academic. I actually needed to photograph the leopard first—and that was far from a certainty.

Mohammed took us for a walk around Ancilotto’s property. He showed us where he and the other askaris had seen the leopard. Letoluai also kindly showed me where he had captured his footage. They showed me animal paths through the bush, firebreaks along the boundary of the property, and open rocky areas with fabulous views out over the plains below.

Deciding on places to put my cameras was not easy. The researchers were aiming to capture side-on shots so that they could identify leopards from their spot patterns. But I’m a wildlife photographer, and I was looking for something quite different: head-on shots and elements of the habitat that would attractively frame the subject. So there is always a trade-off between locations that provide the best chance of capturing any image at all and locations that might result in a more aesthetically pleasing photo. I am usually drawn to the latter. In the end I decided to put two cameras near places that Mohammed and Letoluai showed me, and three on the trail Carey had identified in the morning.

Even with help from Mohammed, Letoluai, and askari, Patrick Lempejo, it was grueling work. By the time the sun went down the five traps were set up, each with two or three flashes on stands weighed down with rocks, and the camera in a strong housing to provide some protection from elephants and hyenas.

The last thing for me to do was fine-tune the position and brightness of each flash. This needed to be done in darkness, and in many ways it is the most critical part of the process. Summoning the mental energy to be creative after an exhausting day was a real challenge. Eventually, two hours after sunset, I headed back to camp. I was weary but excited to see what the next two weeks would yield.

The next morning, I was up bright and early to check the traps. As I opened up each camera housing and pressed the “play” button, I was greeted with the same image: a beautifully lit picture of myself—my final test shot from the night before. I was disappointed not to have captured any wildlife, but not surprised—I never expected this to be easy. I resolved to leave the traps running for a few days before checking them again.

Over the following days, I savored the delicious anticipation of having camera traps in the field, and the knowledge that one of them could hold the shot of my dreams. That anticipation was so sweet and the fear of disappointment so great that I was reluctant to return to the cameras at all.

Eventually, after three nights, I decided I had better check. I started with the two cameras down near Ancilotto’s house. There were some pictures, including one of a lovely striped hyena, which I had never photographed before, but no leopard. Next, I checked the cameras up on the path. On the first two I found a scrub hare and a white-tailed mongoose, but again, no leopard.

I opened up the final camera. I now had no expectation at all of finding a leopard picture. I started to scroll quickly through the pictures. Scrub hare, mongoose, and then … I stopped and peered at the back of the camera in disbelief. The animal was so dark that it was almost invisible on the small screen. All I could see were two eyes burning brightly out of a patch of inky blackness. The realization of what I was looking at hit me like a lightning bolt.

My first thought was not to celebrate; it was too soon for that. Was the image sharp? I zoomed in and it seemed good, but I know from bitter experience that you can’t tell for sure until it is on the computer. All I wanted was to get back to camp as quickly as possible.

I removed the memory card from the camera and cradled it in my hand like some sort of fragile, priceless artifact. After resetting the trap, I hurried back to my car.

I drove back to camp in a haze, trying to process what this picture meant. It was a dream come true. This was likely to be a defining moment in my career, more important than anything I had achieved before. Never had I captured an image of something so rare, or of a creature more stunning. I couldn’t wait to show the image to my family, who were all back home in the United Kingdom. I had been careful to manage their expectations, and so they probably weren’t expecting me to be successful. How should I tell them? How should I break the news to the guys at camp? I savored these thoughts as I negotiated the winding dirt tracks.

I reached camp, parked, and raced to my tent. I wanted to avoid everyone until I saw the image on my computer and was sure of what I had. Waiting for my laptop to power up and for the image to import was excruciating. And then there it was. In the darkness of my tent, on the bright laptop screen, I could now see the animal properly. It was so beautiful it almost took my breath away. I zoomed in and the image was sharp. My eye wandered around the frame, looking for distractions. There were some bright blades of grass that irritated me, but nothing serious. The image was better than anything I could have hoped for. I took a deep breath and exhaled slowly. It was going to take a few days for this to sink in.

I picked up my phone and tapped out a message in my family chat group.

Will: Who wants to see a black leopard?

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook