These Stunning Botanical Images Are Blueprints of the Past

Two 90-year-old albums document what a 12-year-old photographer did on her summer vacation.

It’s the summer of 1929. In a few months, the New York Stock Exchange will collapse, and a new generation of American photographers—Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, among others—will soon capture the pain and uncertainty of those displaced by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression.

But in Rye, New Hampshire, a young girl is crouching on the shoreline, gathering flowers for a series of photographs inspired by some of the medium’s earliest explorers. She is working with photography at its most elemental—capturing sunlight on a sheet of paper washed with salts and fixed in water.

Helen Chase Gage was born in Bronxville, New York, in 1917. She studied art history and fashion at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute, and later worked as an executive at the Westchester branch of Lord & Taylor.

Gage was also an active member of the Bronxville League for Service, a philanthropic organization that founded and staffed a dental clinic for low-income patients and once purchased an ambulance for the local hospital. As a volunteer, Gage hosted sewing circles, organized fundraising galas, and worked as the league’s archivist.

But her buzzing professional and social lives belie her earliest self-expression, as a photographer.

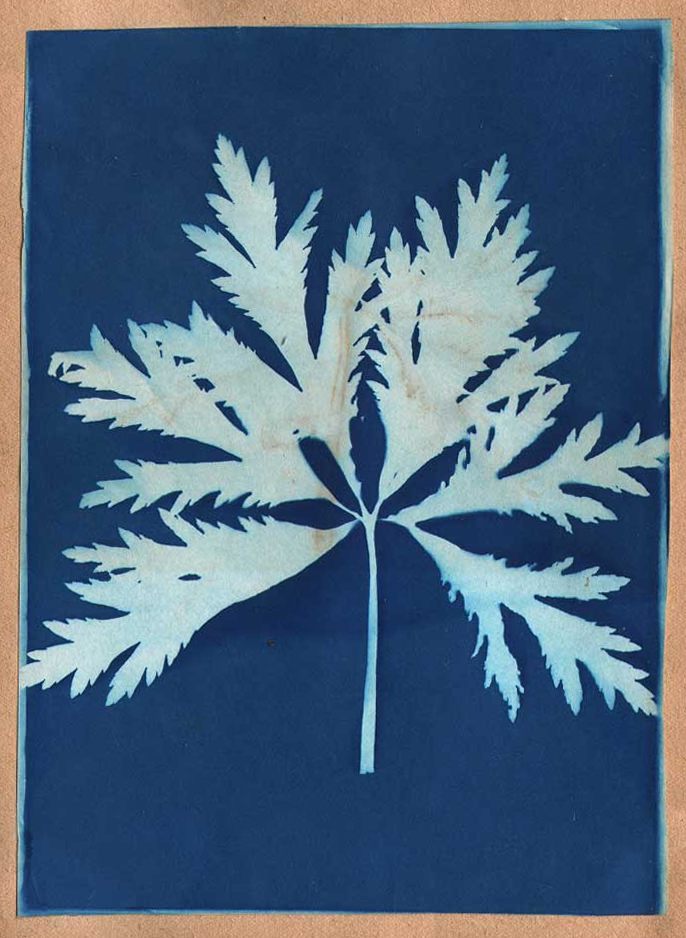

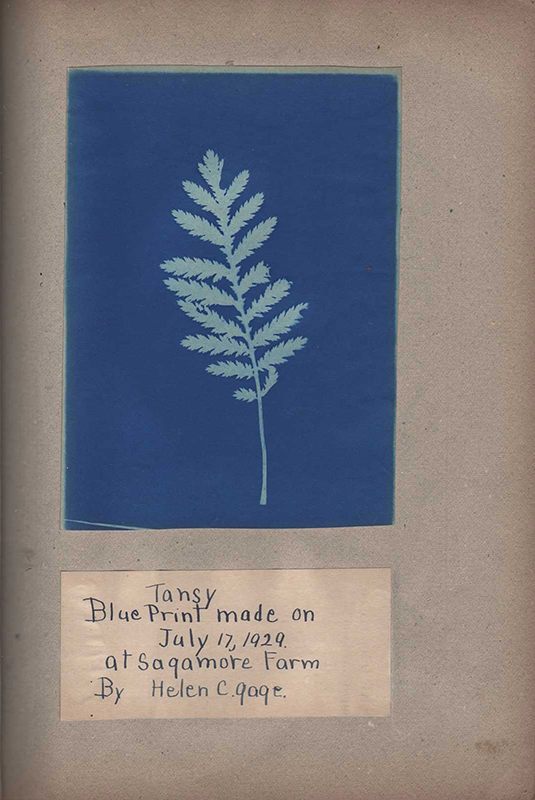

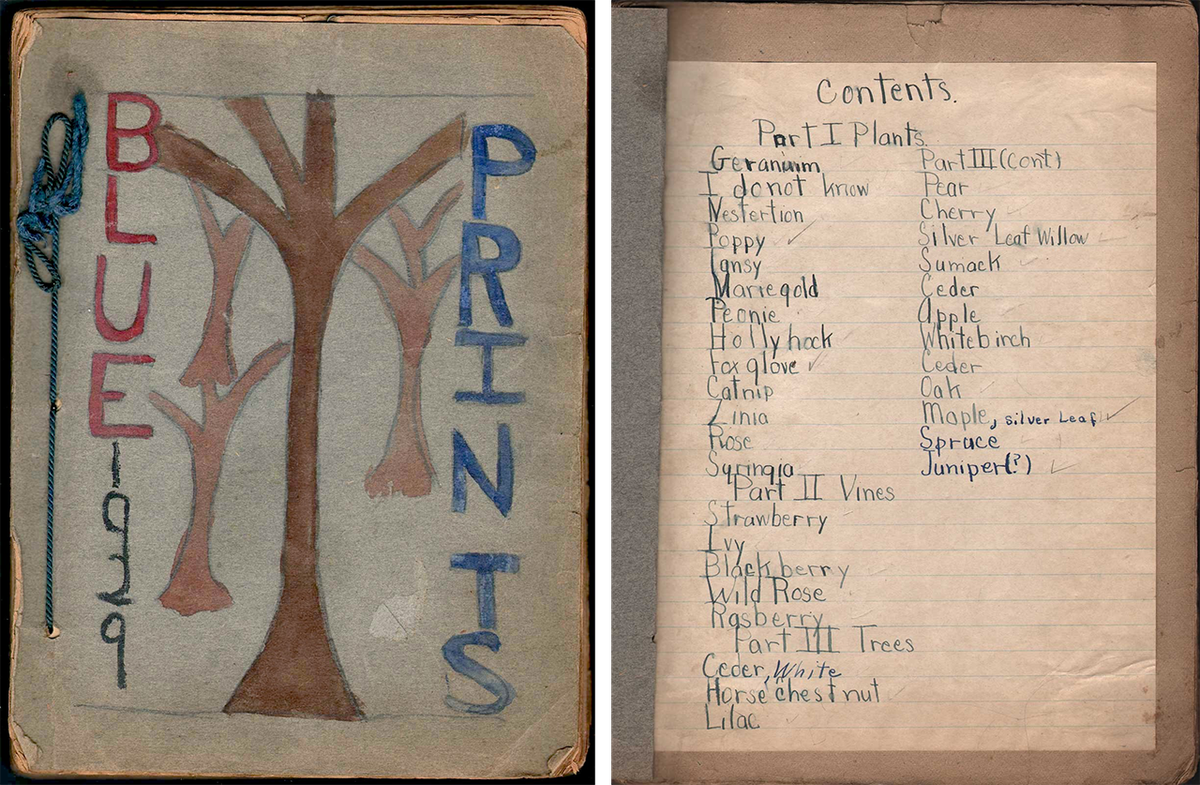

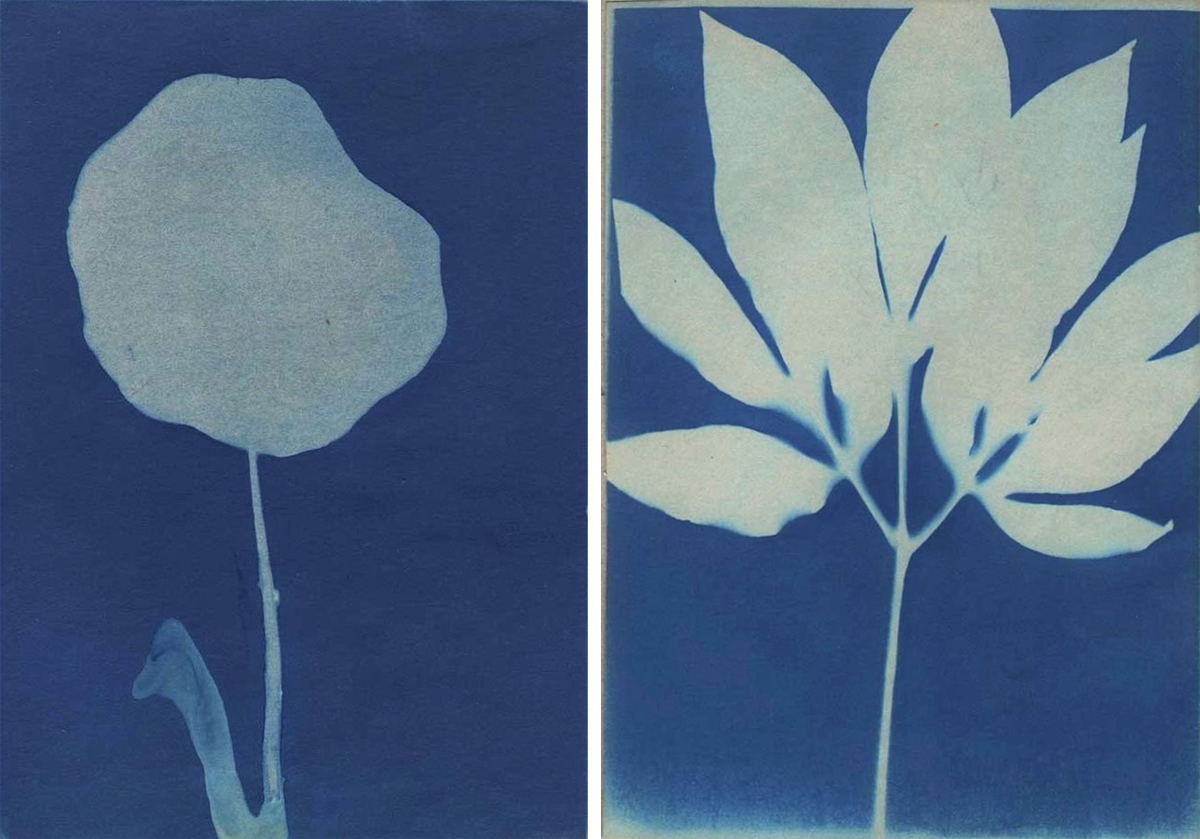

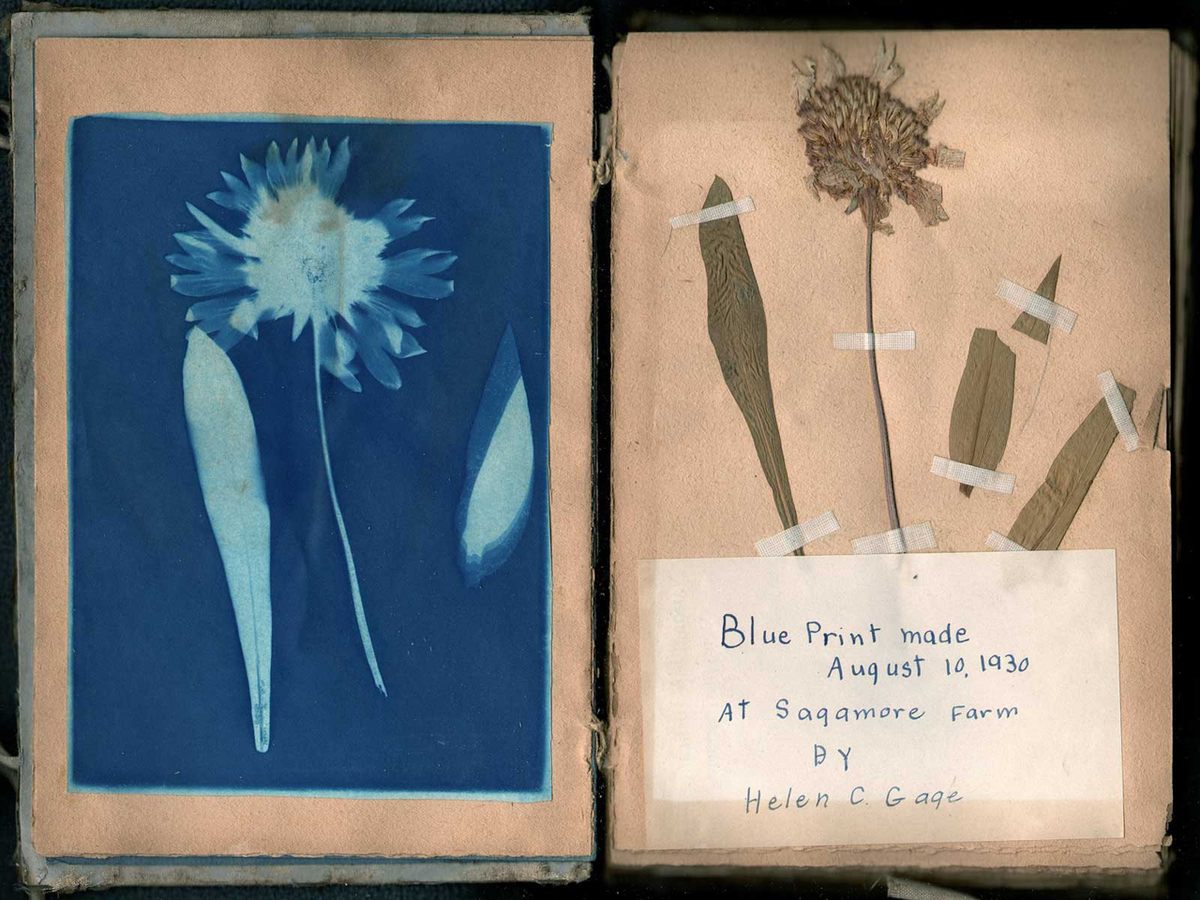

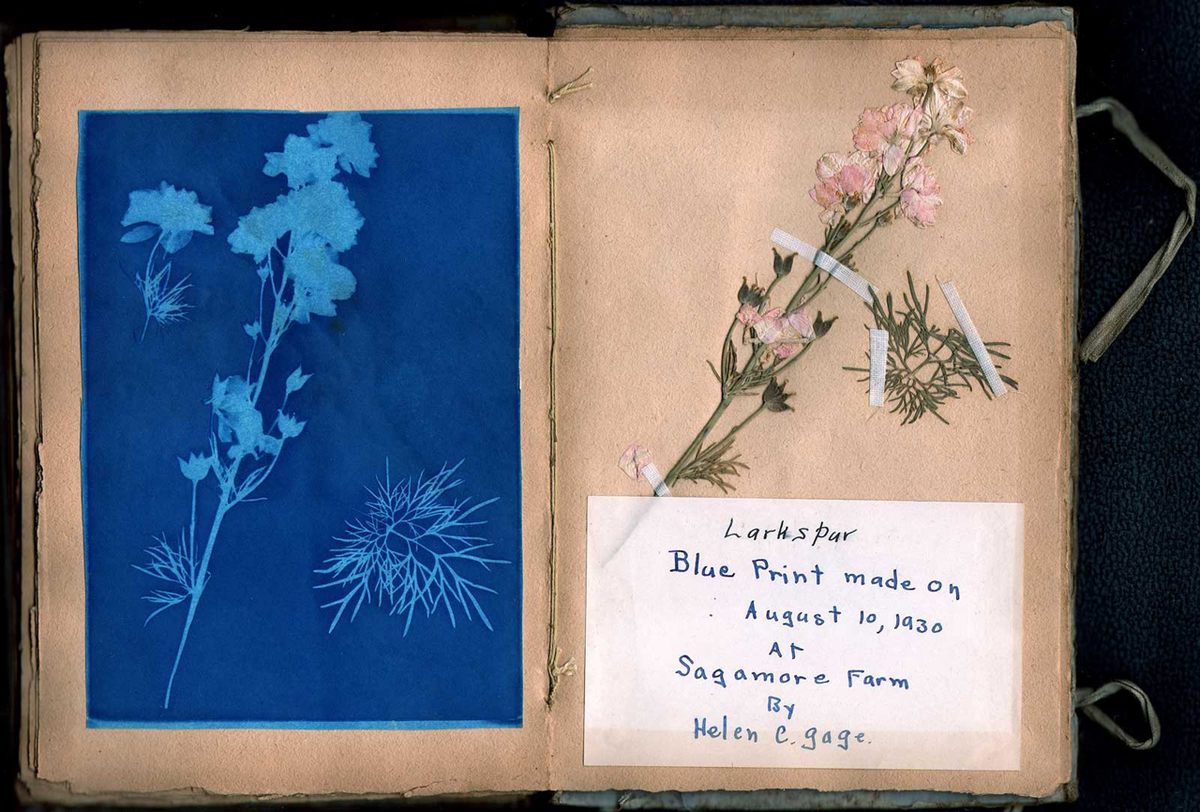

In that summer of 1929, Gage, then 12 years old, created the first of two albums of botanical cyanotypes. Using plants she found on her family’s summer estate, Gage prepared a stunning series of photograms. These unique images trace the buds of a larkspur, the curl of a leaf, and a blob of nasturtium, seemingly floating in a pool of the deepest Prussian blue.

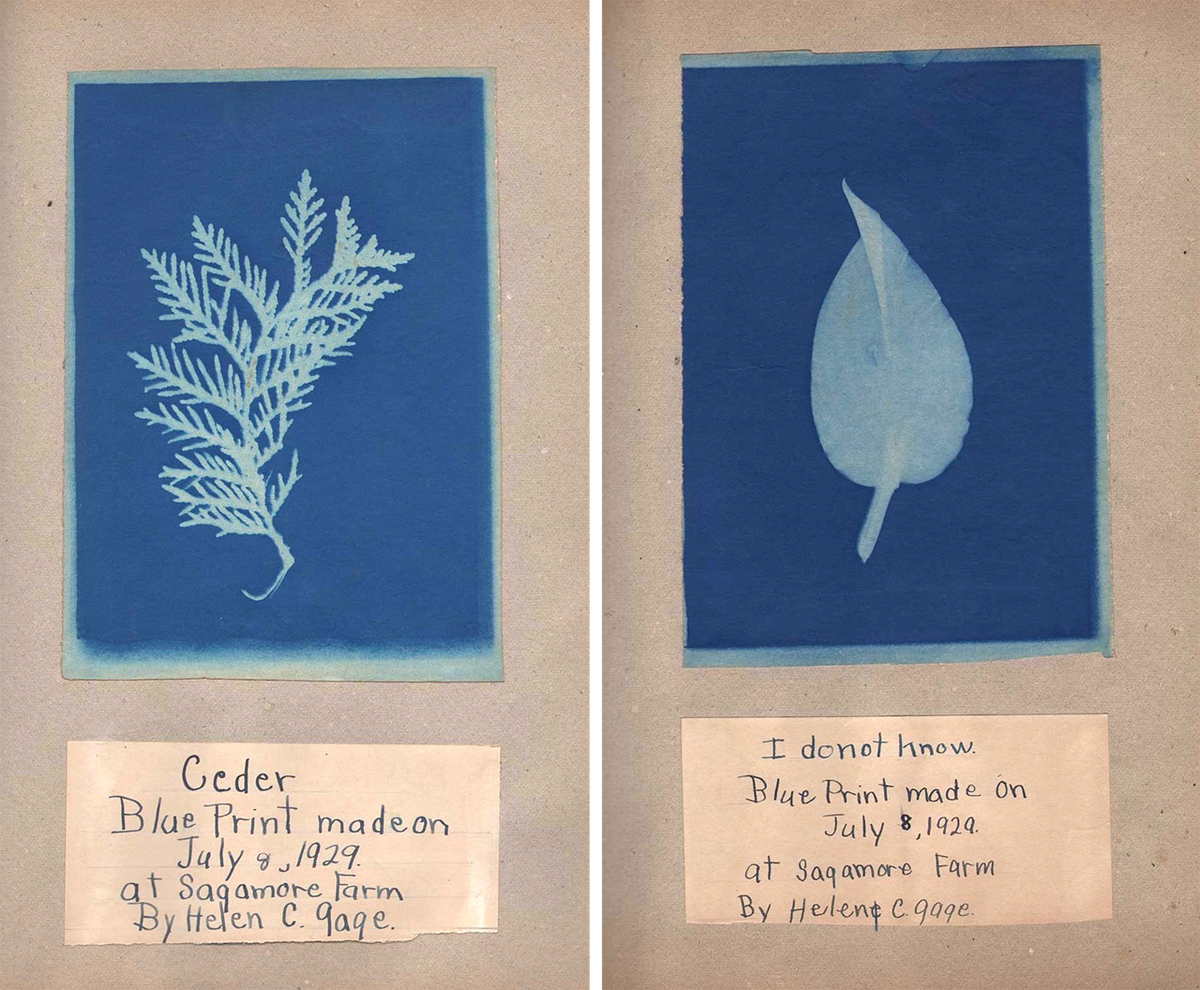

Gage came up with the idea for the project just before her summer holidays, when she watched Anna Greve, head of life sciences at Bronxville Elementary School, turn a sheet of blueprint paper into a light-sensitive canvas. So inspired, Gage wrote, “I asked Daddy to get me some blue print paper. One week end when he came up to the country he brought me a yard square.”

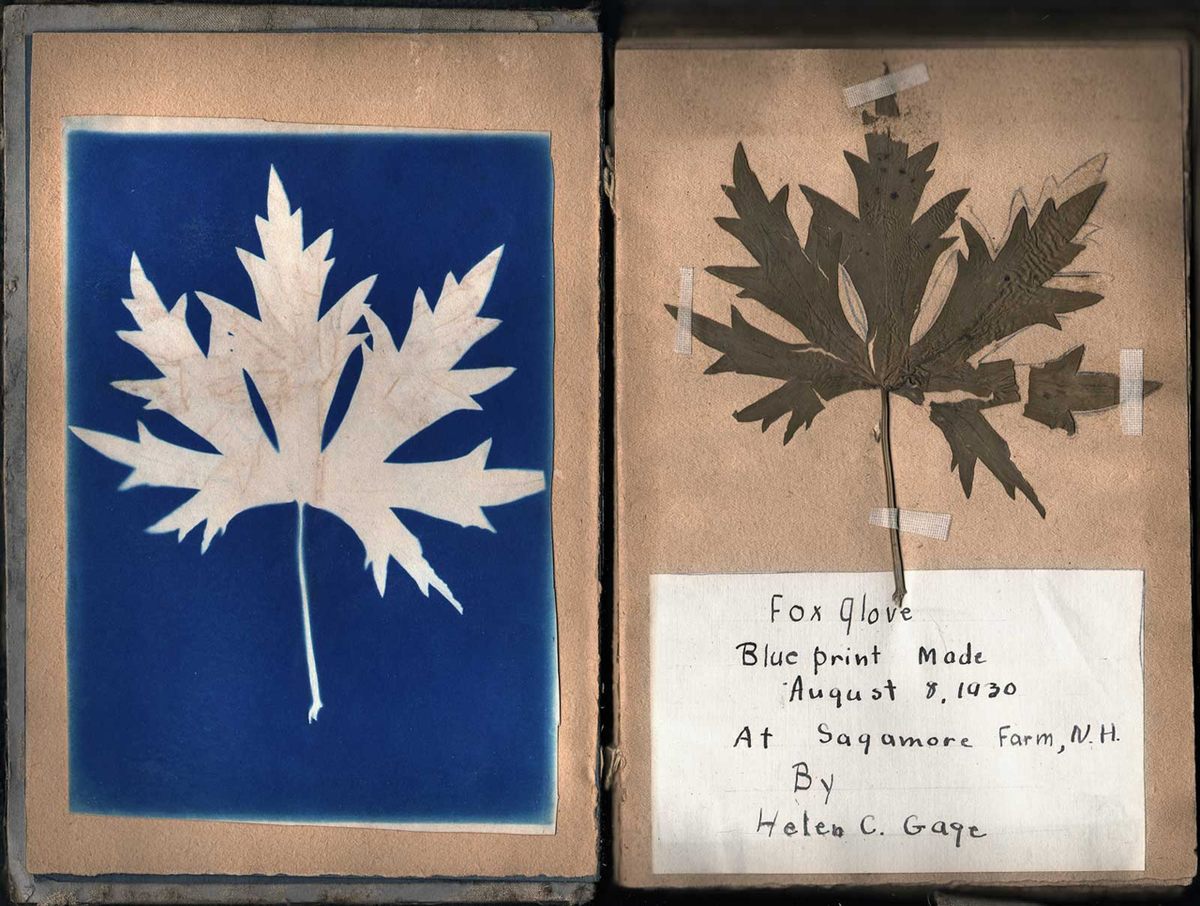

Gage’s project flourished over two summers at Sagamore Farm, the holiday home on Odiorne Point that her mother bought in 1918. The gardens there were full of summer-blooming plants for Gage to gather—poppies, pinks, and the aptly named Helen’s flower. A grove of sugar maples stood on either side of the road leading to Sagamore Farm, which Gage used to make a constellation of leaf prints.

Working on the shores of the Gulf of Maine, Gage experimented with a photographic technique that dates back to 1842. While Sir John Herschel, a British chemist and astronomer, created the cyanotype process, it was Herschel’s friend, Anna Atkins, who established the medium as an essential tool for scientific illustration. In 1843, Atkins published the first of eight volumes of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, thought to be the first book primarily illustrated with photographs.

Gage’s 1929 album includes a charming, handwritten introduction that describes her process to the viewer. “I will answer the question that will probaly [sic] come to your mind,” writes Gage:

How do you use it? You put the leaf or whatever you want to print on the glass and then put the blue print paper on top. Put it in the sun untill [sic] it turns white. Take it out of the case and put it in a pan of water untill [sic] it turns blue. Then take it out of the water and let it dry and your blue print is all done.

When the family returned to Sagamore Farm the following summer, Gage prepared another album. Decorated in a handmade, block-printed fabric, the album functions as an herbarium and a photo collection in one. It also demonstrates Gage’s technical and conceptual growth from one year to the next, creating an unusual botanical and photographic record in the process.

Of course, those bucolic summer days couldn’t last. As the Second World War loomed, the U.S. government expropriated Odiorne Point, driving a dozen families—including the Gages—from their land. The site is now Odiorne Point State Park, where the stone foundations of Sagamore Farm lie alongside the decommissioned remnants of wartime fortification. Tansy, a wildflower Gage once collected in the area, still grows along the salty shoreline.

Gage lived with her parents for most of her life, but married in 1970, at age 52. In their wedding portrait, Gage—haloed by a short, white veil—beams happily as she stands with her husband, a Bronxville man named Arthur W. Miller. The couple was married for nearly 12 years before Gage died, in 1982, at the age of 64.

Thirty-six years later, in 2018, a collector named David Spencer bought Gage’s cyanotype albums—previously owned by her younger brother, Edward Augustus Gage—from a New Hampshire dealer.

Gage’s pastoral summers are immortalized by these albums she made as a girl. Referencing some of the earliest experiments in botanical photography, she breathed new life into the genre while establishing a creative voice that would serve her well throughout her relatively short life.

This is what Helen Chase Gage did on her summer vacation.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook