The Brutal Bull-and-Bear Fights of 19th-Century California

It’s hard to imagine now, but cruel bloodsport was once part of people’s Sunday routines.

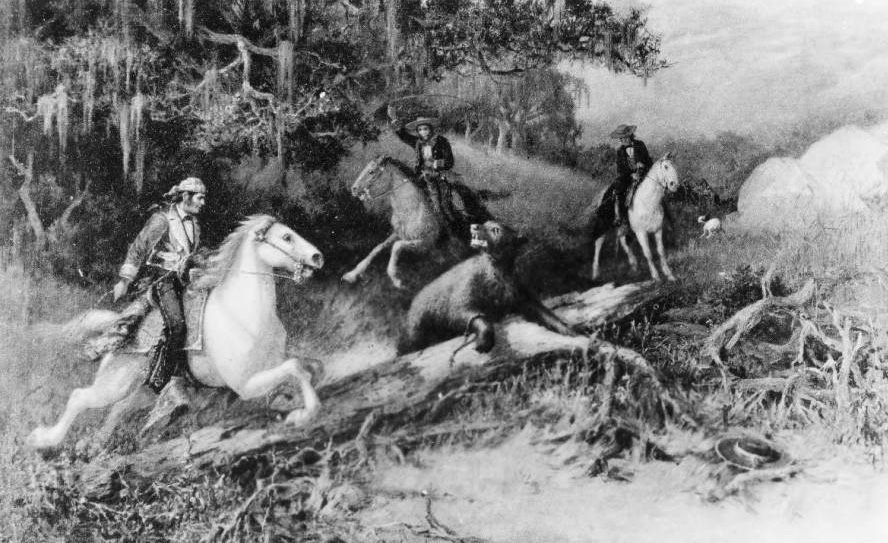

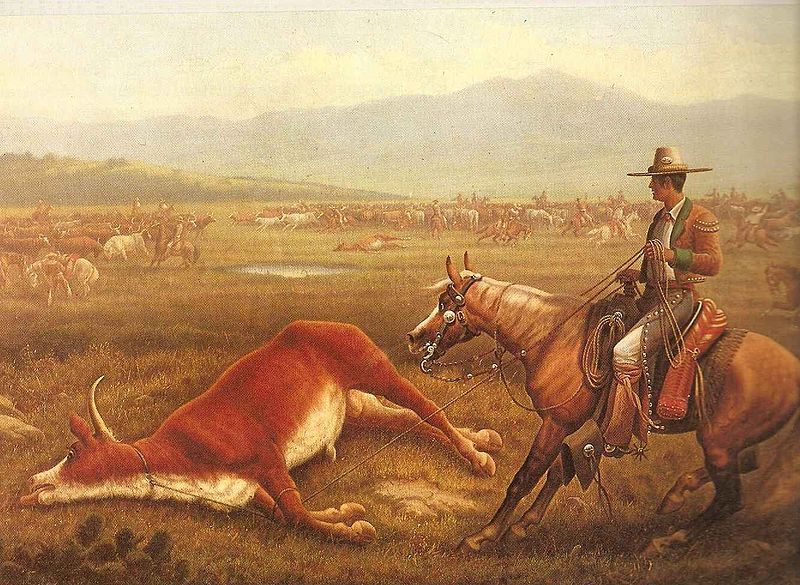

High in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, in the violent years leading up to the Mexican-American War of 1846, lasso-toting horsemen known as vaqueros hunted an animal that is now extinct: the California grizzly bear.

Before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, it was believed that California held around 10,000 grizzly bears. In the 19th century, California grizzlies were most sought for their intrinsic fighting qualities, especially when coerced into combat with a bull—an event that served as entertainment for a crowd on many Sunday afternoons.

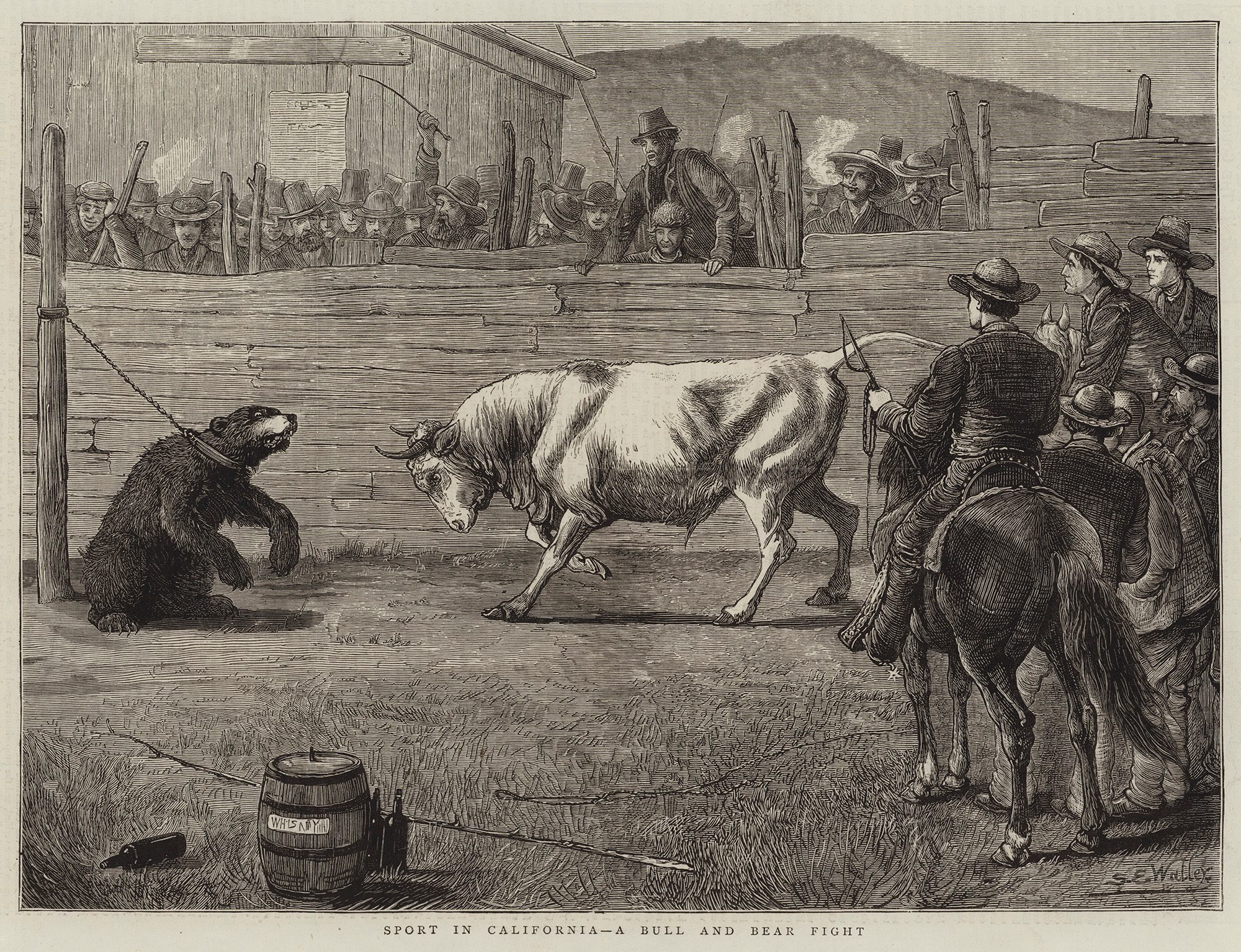

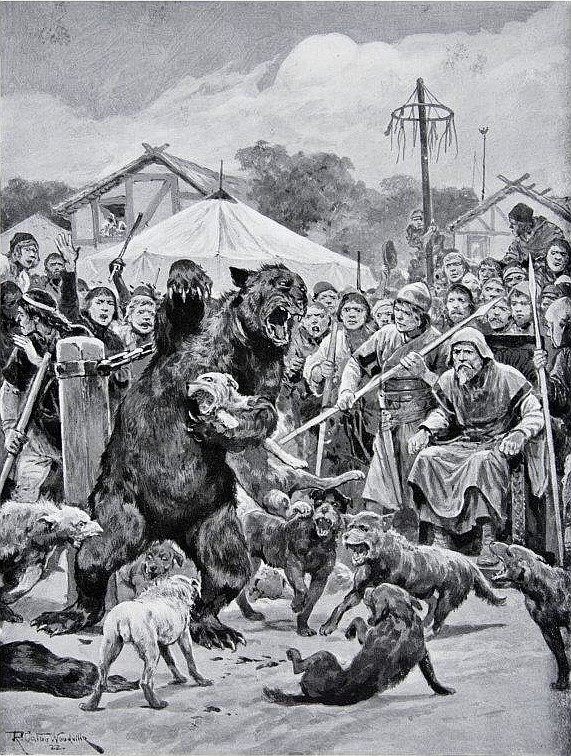

In the small cities and towns that peppered the valleys and coastal cliffs and mustard fields, a curious bloodsport had taken hold. Bear-baiting was brought to California by the conquistadors, but the sport itself was old as Rome. London in the Middle Ages built great amphitheaters known as bear-gardens to host the events. But in 19th-century California, the venues were more temporary and crude. Often known as “pits,” the slapdash arenas were built of split-board fencing and reinforced with heavy logs and adobe. A raised viewing platform was constructed for women and children, a family affair, while the men remained on horseback outside the barricades, raetas (braided-oxhide lassos), rifles and revolvers at the ready just in case the bear decided to climb its way out.

Such occasions usually commenced on Sundays, after church, when the townsfolk gathered after their pious songs and prayer, and slowly made their way to the town square toward the sounds of spectacle. As Hubert Howe Bancroft, American historian and ethnologist, wrote in California Pastoral, “A bull and bear fight after the sabbath services was indeed a happy occasion. It was a soul-refreshing sight to see the growling beasts of blood tied with a long raeta by one of its hind feet, as to leave it free to use its claws and teeth.” And there the spectators would find the vaqueros from the mountains clamping irons on the grizzly and blooding it with small dogs sacrificed to keep the bear in the mood.

If the grizzly was the symbol of California, then the symbol of Spain was destined to be its foe, two species that under normal circumstance would have never faced each other in the wild. Toward the pit would be led a Spanish Fighting Bull, that proud trot and deep black hide, its horns decorated with garlands of flowers and always—somewhat baffling—the home favorite.

The bear and bull fight was the main event, with an undercard of cockfighting and dogfighting to whet the crowd’s appetite for death. But then there would be other activities on the periphery, strange contests that usually involved a display of horsemanship, sharpshooting, or lasso work, anything to prove to the churchgoers that you had the right stuff. Of course there would be the requisite horse racing, but there were also other peculiar feats such as “to place on the ground a rawhide, and riding at full speed suddenly rein in the horses the moment his fore-feet struck the hide,” a prototypical driver’s test of sorts.

A more amusing form of horsemanship would be to bury a rooster in the dirt up to its neck, and, as California Pastoral says, “at a signal a horseman would start at full speed from a distance of about sixty yards, and if by dexterous swoop he could take the bird by the head, he was loudly applauded.” But if the rider failed, “he was greeted with derisive laughter, and was sometimes unhorsed with violence, or dragged in the dust at the risk of breaking his limbs or neck.”

Finally the moment would arrive. The bear and the bull, secured with shackles and ropes, would be led into the pit by shortcoat and sash-wearing caballeros—gentlemen of high standing in the town. The bull and bear would be tied together by a long length of rope, but short enough to keep the two gladiators in each other’s company. By now the crowd would be in frenzy, the smell of grilled meat in the air and the swilling of spirits from black bottles. As the crowd pressed forward, baying for the release of the beasts, an officiator would climb to his position on the raised platform, women and children behind him, and fire a pepperbox pistol in the air to start the contest.

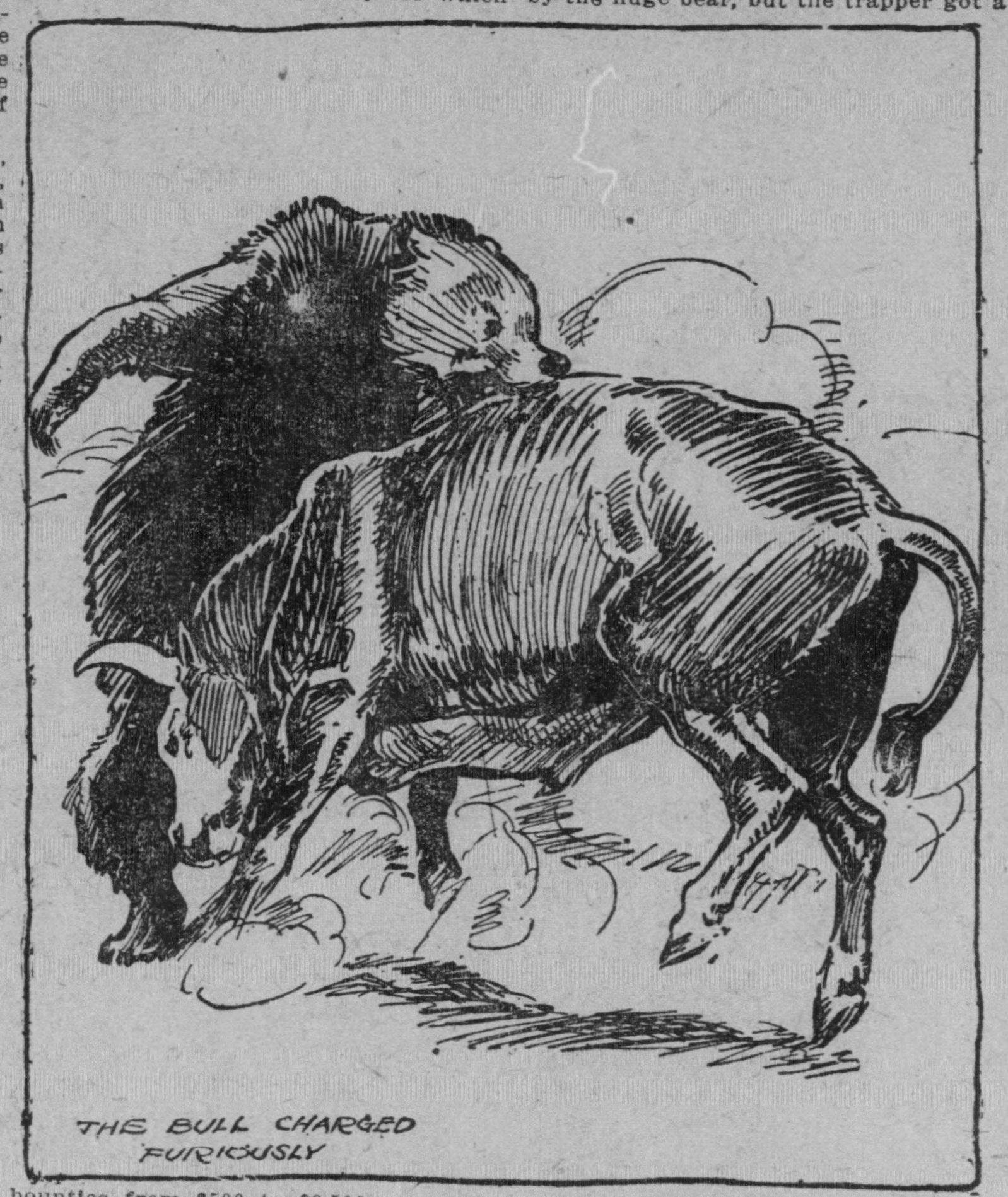

At the outset, the bear would usually hang back, taking a defensive posture on its hind legs, while the bull was often the first to attack, charging with head down and horns lethal. It was generally understood by eyewitness accounts that the bear held the advantage in the fray. While the bull had a deadly lunge, the bear could parry the advance and grab the bull by the head, sinking its teeth into the bull’s neck, or on one account, biting the bull’s tongue, which would have undoubtedly released a crowd-pleasing bellow. At such times the vaqueros would jump in and break up the fight to save the bull and prolong the drama. “I was present,” stated a spectator named Arnaz in the pages of California Pastoral, “when a bear killed three bulls.” Often a single grizzly would fight many bulls consecutively until the home team won. “Sometimes the bull came off victorious, and at other times the bear, the result depending somewhat on the ages of the beasts.”

What further added enjoyment of the bloodsport was how differently the two animals fought. The bear would often stand and take mighty downward swipes with its paws, while the bull would charge low and rush upward for the gore.

If this sounds familiar, like a word on the tip of your tongue you can’t quite remember, that is because the bear and bull fights of California inspired the modern day colloquialism of Wall Street: bull markets and bear markets. And the rest is just history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook