How a Candy Craze Almost Wiped Out the Barrel Cactus

Fake legends and Southwest imagery sold crystalized cactus to Americans.

In 1891, on the final leg of his long journey from southern Italy to Arizona, 12-year-old Dominick Donofrio looked out the train window and saw his future take shape. For miles, the Southwestern desert was an uninterrupted forest of cacti: tall saguaro and organ pipe, clusters of cholla and prickly pear, and everywhere, the giant, round barrel cactus, known by Native Americans as visnaga.

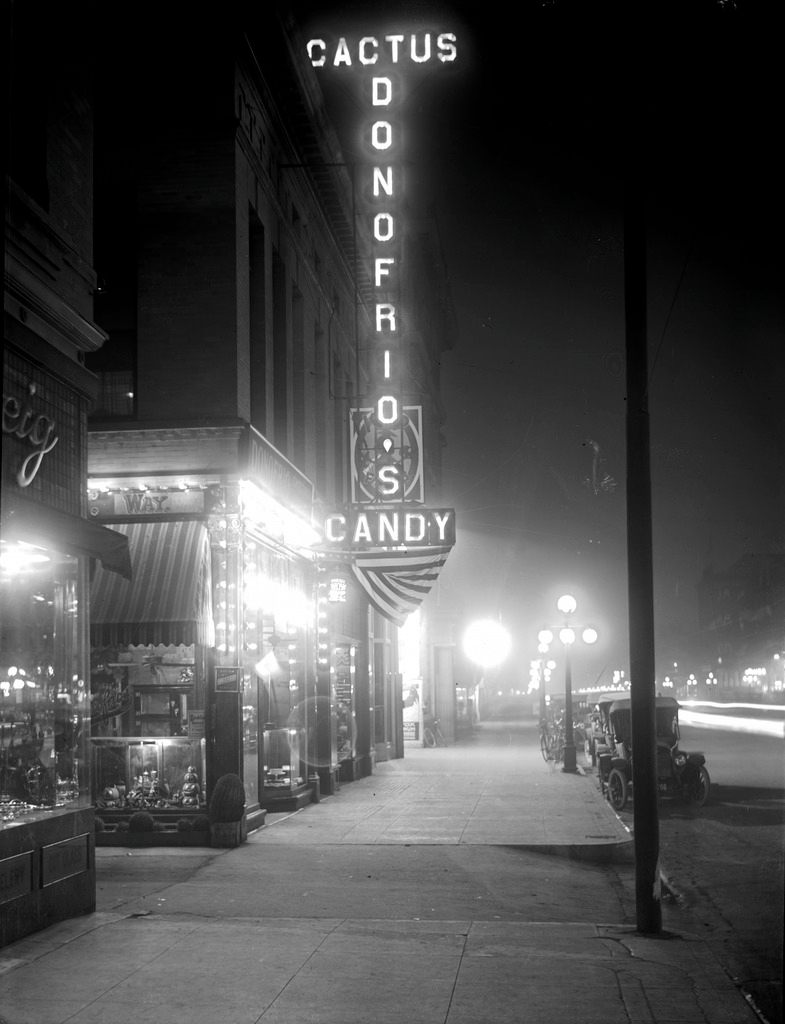

Arriving in Phoenix, Dominick went to work at his older brother’s booming confectionary. But he yearned to make a mark of his own. “It came to my mind that millions of dollars could be made out of cactus,” he would later recall. For a decade, a scheme combining cactus and candy “preyed on my mind until I could see myself counting the money.” In 1905, Dominick bought the store from his brother and realized his vision right away.

For centuries, the Pima and other tribes used the visnaga’s cooked pulp as food and its spines as fishing hooks, and candy from the plant was a well-known homemade treat in Mexico. But “Donofrio’s Crystallized Cactus Candy” marked its first industrial production in the United States.

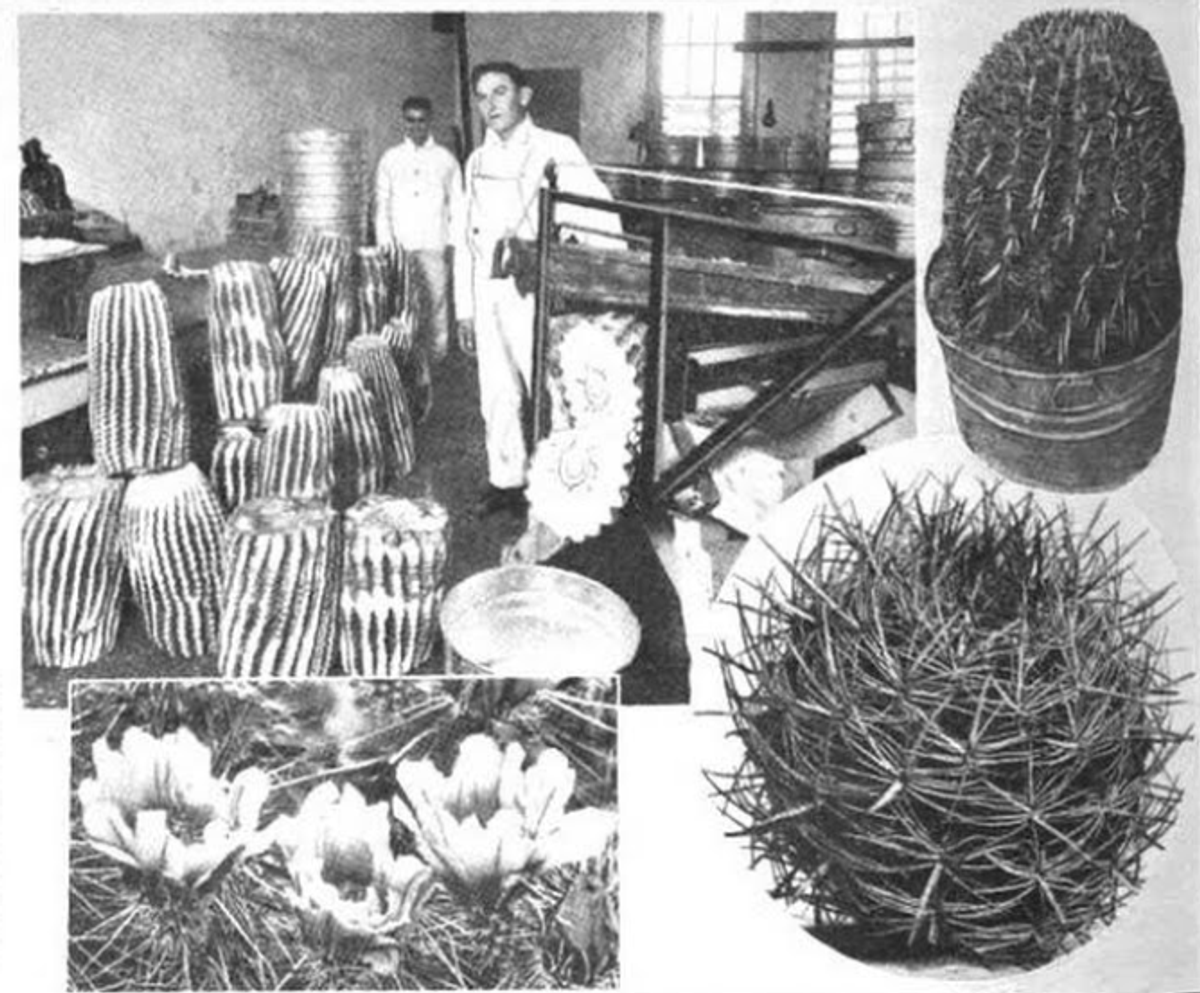

The process involved a startling amount of labor, cactus, and sugar. Out in the desert, Donofrio’s hired hands hacked down plants ranging from two to five feet tall and 80 to 100 pounds, then de-spiked and trucked them back to the factory. Here, workers peeled, cored, and sliced up the visnaga into small cubes, boiled them into tenderness, and cooked them in sugar-syrup over and over again, hotter and hotter. Then, via a top-secret Donofrio process, workers crystallized the cubes in vats, cooked and crystallized them again, and set them out on racks to harden. The result was something like a gumdrop, with a sugar crust and a gelatinous core.

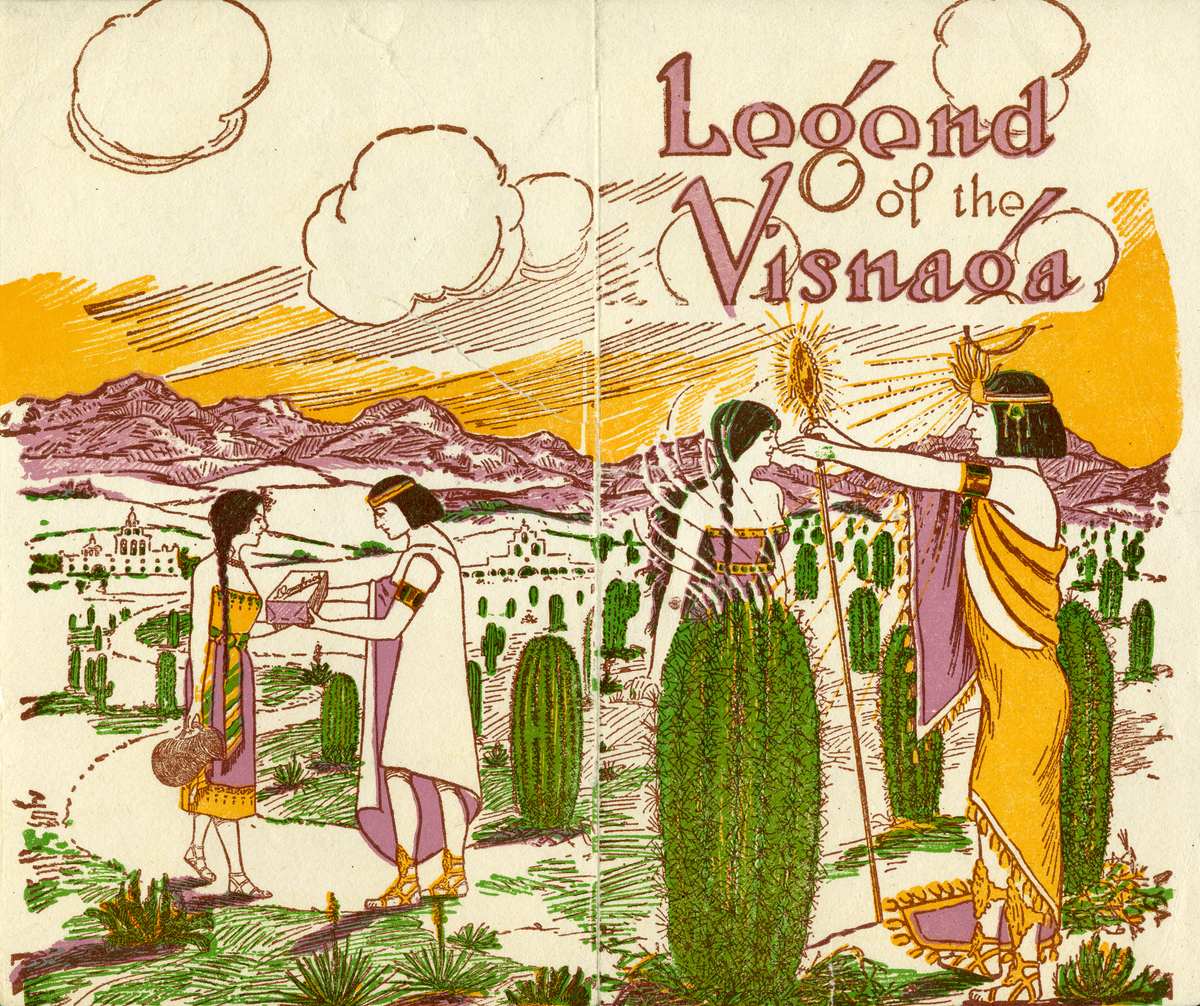

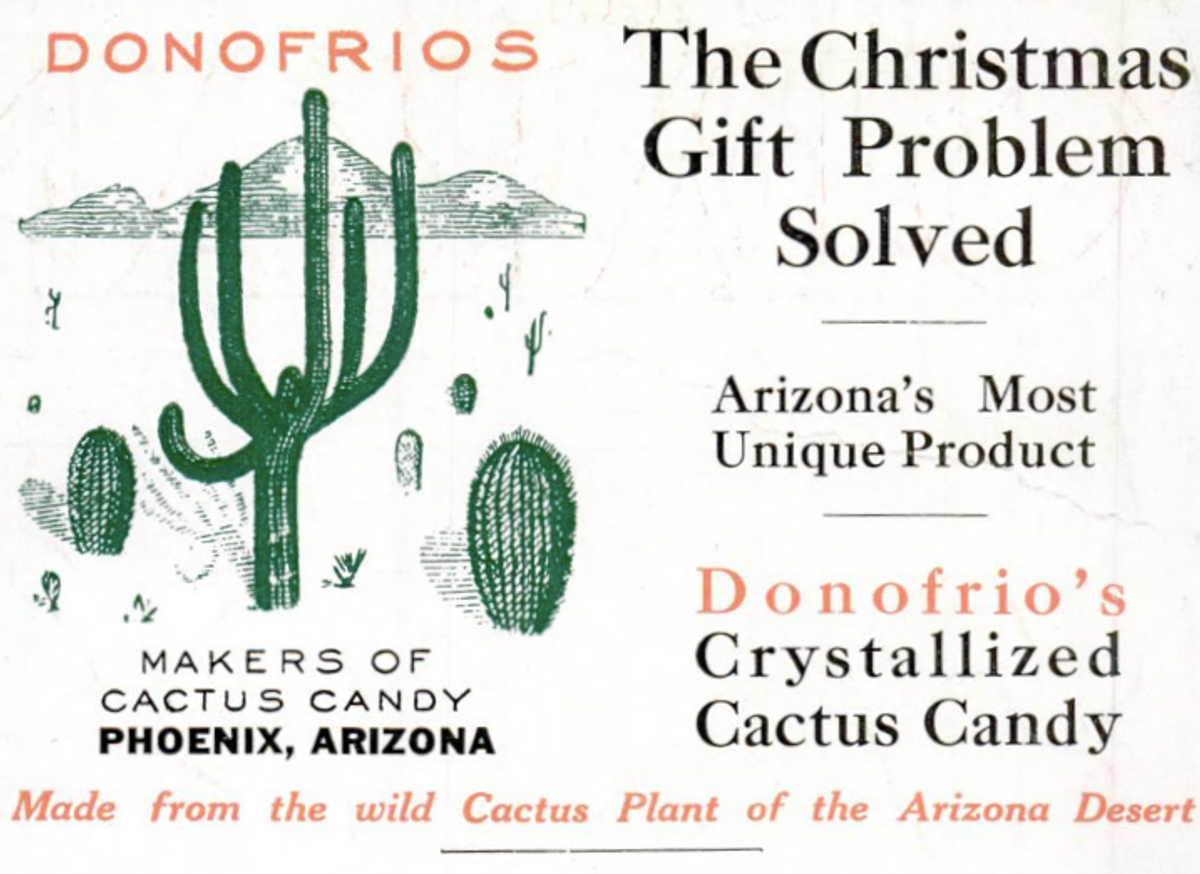

“That man’s name will go down in history who first converted the ugly desert plant into such a delightful delicacy.” Thus boasted one of Donofrio’s earliest ads, inaugurating a decades-long marketing juggernaut. Donofrio targeted Christmas shoppers, guilty husbands, and snowbirds anxious to impress friends back home. Cactus candy was “pure, wholesome, nourishing, [g]ood for breakfast, luncheon, dinner,” his ads claimed, thanks to the pure air and sun of the desert. Playing on a romanticized vision of the Southwest, his cactus candy came in boxes illustrated with Spanish missions and sandal-wearing Native Americans.

On top of that, Donofrio’s promotional materials spun an elaborate, fake origin story for both candy and proprietor. According to “Toltec legend,” the Sun God imprisoned a beloved maiden’s soul inside the visnaga to protect her purity. This legend, claimed Donofrio’s, then inspired a Toltec wedding ritual, where prospective grooms had to make cactus candy by ripping out thorns with their teeth and crystallizing pulp with wild honey.

That wasn’t all. At least one brochure stated that the Donofrio family was not Italian, as their name might suggest, but rather had descended from a long line of Mexican confectioners, beginning with Donofrio, royal candy-maker to an ancient Toltec king. Maybe these claims were meant to be tongue-in-cheek, but newspapers and trade journals regurgitated them wholesale.

By all accounts, the gimmickry paid off. Mail-order business soared, and Donofrio’s new treat popped up in candy stores across the nation. The company produced 15,000 pounds of the stuff in 1920 alone.

A year later, another Mediterranean immigrant took up the cactus candy mantle 400 miles away, in El Paso. Originally from Greece, George Carameros and his brother-in-law made candy in Mexico City until around 1918, when the Mexican Revolution forced them north. Then they bottled beer and soda in Texas until Prohibition killed that business, too. Wandering through an outdoor market in search of a new calling, Carameros happened upon a cactus candy stand, gave the merchant five dollars to show him how it was made, and the rest was history.

To announce his new business, Carameros displayed a 300-pound visnaga in downtown El Paso. And he upped the cactus candy game in more ways than one. He made cactus preserves and ice cream, infused the candy with fruit flavorings, coated it with chocolate, and touted an allegedly unique method of anti-mold preservation. His candy was hawked on every transcontinental train, in restaurants and hotels across the West, and even aboard international steam ships. In 1927, Carameros produced 165,000 pounds of cactus candy, and nearly twice as much a decade later.

Success bred plenty of imitators. Throughout the 1920s, smaller, shorter-lived cactus candy ventures sprouted up across Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and California; wherever the open desert offered visnaga for the taking. Gushing at the trend, one news report opined optimistically that “the supply [of barrel cactus] is said to be almost inexhaustible.”

But while cactus candy appeared to be all the rage, whisked from shelves and gobbled by the handful, one thing was missing from the breathless coverage: a description of its actual taste.

Then, in 1924, a cranky El Paso journalist named Norman Walker opted to speak his truth, via a colorful survey of Mexican candies, syndicated nationwide. “Eating Mexican cactus candy is like kissing your sister,” he began unpleasantly, “it fails to satisfy.” After skewering all the cheesy marketing, he got to the bottom of why so many new companies seemed to fail: “Some success has been attained, but it does not repeat itself in sales.” In other words, lots of people bought and sampled one box of cactus candy, but few chose to ever do so again.

But it didn’t make a difference. The trend continued unabated, and by the late 1920s, in California at least, the desert’s supply of visnaga no longer looked so inexhaustible. “Our Sweet Tooth Eating Up Cactus,” one paper reported, echoing a lament among Los Angeles-area garden clubs that automobile access into the desert was causing the demise of a rare botanical treasure. “Barrel cactus on the deserts of San Bernardino and Riverside counties is being taken out by the truckloads daily for the manufacture of cactus candy,” railed one early conservationist.

In 1928, both counties adopted legislation banning removal of desert plant life, but the threat persisted. Over the next decade, alarmed California citizens reported truckloads of pilfered cacti being smuggled along back streets, beloved fields of cacti hacked to the ground, and a Los Angeles candy plant overflowing with giant, freshly-butchered visnaga. Cactus was seized not just for sweets, but for home gardens, shoe-heels, even goldfish bowls. Foreseeing mass extinction, “friends of the desert” groups sprung up across Southern California, lobbying lawmakers for wildlife protection and transforming the public’s vision of the desert, from bleak dust bowl to environmental treasure.

Following in California’s footsteps, Arizona adopted protections for its desert plants, including the endangered giant barrel cactus. But Dominick Donofrio was undeterred. For two more decades, he hired a Native American to procure the cactus from his reservation, where harvest by permit was still allowed. And in El Paso, Carameros continued to send his workers deep into New Mexico’s Organ Mountains for visnaga, until he sold the candy business in the early 1950s. Only in 2014, thanks to a tireless coalition of desert-lovers, was this region granted federal protection under the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks Conservation Act, which named the barrel cactus among its treasured species.

Once facing extinction, visnaga can be found across the southwestern deserts and in Mexico. But it has an uphill battle for survival. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the particular species used for candy as “vulnerable” with “population decreasing” in the United States and “near threatened” in Mexico, urging further action to protect them from theft and destruction.

Cactus candy remains an Arizona novelty, on sale alongside cactus jelly in airport gift shops. But these days, most candy is made from prickly pear fruit, rather than the pulp of the imperiled visnaga. So a taste of the desert is now more sustainable.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook