The Gay Coffeehouse Where Off-Off Broadway Theater Was Born

Remembering the Caffe Cino of 31 Cornelia Street, New York.

Joe Cino didn’t look much like a dancer. Barely five feet nine inches tall and sometimes described as “roundish,” Cino was generous of lip, cheek, nose, girth, and spirit, with an open face capped by thick, dark curls. In 1948, at about 16 years old, he had moved from Buffalo, New York, to New York City by bus in a blizzard, and for the next near-decade, tried to make it as a dancer. It didn’t work out. And so, on a Friday in early December 1958, he took his $400 in savings, and opened a coffeehouse on Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village. It was originally called the Caffe Cino Art Gallery, according to its National Register of Historic Places application. But it would soon become known only as the Caffe Cino.

Years later, Cino would explain that he had hoped for “a beautiful, intimate, warm, non-commercial, friendly atmosphere,” one where his friends—who, like Cino, were mostly gay—could come without fear of harassment or prejudice. Instead, by chance, the Caffe Cino became a birthplace of Off-Off Broadway Theater and, for many, the lifeblood of Greenwich Village’s coffeehouse culture.

At that time, New York’s theater was generally limited to Broadway, which featured high-end, professional work, and Off-Broadway productions, which were marginally less expensive and catered to audiences of up to 500. Off-Off-Broadway was different—experimental, intimate, uncommercial. For many theatrical scholars and critics, it began with the Cino.

The playwright Robert Patrick, now in his 80s, first stumbled upon the Cino almost entirely by accident. He had left his summer job as a dishwasher at a theater in Maine and taken a bus back to New Mexico, where he had gone to high school. The bus stopped in New York, where he planned to visit a college friend and take a glance at Greenwich Village, “which I’d always heard about,” he says. “I got to Greenwich Village, and I followed the first long-haired boy that I’d ever seen, he was selling jewelry on the street.” He followed him down a side street and into a coffeehouse where, he recalls, two men were rehearsing a scene from The Importance of Being Earnest. “And I stayed.”

In the introduction to the anthology Return to the Caffe Cino, editor Steve Susoyev writes: “No two people agree about anything that happened forty-plus years ago at 31 Cornelia Street in New York City.” But Patrick remembers a café that was dark and smelly, with a ceiling bedecked with fishnets, chimes, and tinsel. “There was always something twinkling or tinkling,” he says. The walls had a thick crust of paintings, posters, prints, and photographs torn from magazines. Christmas tree lights glinted off tin foil and glitter stars. Religious icons jostled for space with Valentine’s cards. (Periodically, all of this would be removed to deal with a recurring plague of cockroaches, and then painstakingly returned to its place.)

“There was a jukebox, which was full of opera records,” Patrick says. (Cino eschewed folk or popular music.) “There was a huge coffee-grinding machine, which was just decoration.” It didn’t work, so Cino borrowed coffee pots from around the neighborhood, hid them under the counter, and pretended to be getting the coffee out of the machine. There was also no staff. “I had never thought of having a waiter,” Cino said, later, “so one of the friends took care of the other friends.”

“I loved the place,” says Patrick. “I loved everything about it.” He abandoned the return trip to New Mexico, took jobs in the neighborhood as a typist, and spent evenings and weekends at the Cino doing volunteer labor—“as a janitor, or a waiter, or a doorman, or whatever they needed, just to be there.” He was dazzled by the wit of the people he met; their creativity; Cino’s warmth and sweetness in blue jeans and yellow construction boots. “It was everything a New Mexico art fairy bookworm could hope for.”

On opening the café, Cino had imagined art exhibitions, occasional poetry readings, and lectures—perhaps even the odd dance performance. But the readings grew more and more popular, and so what was first a weekly occurrence gradually bled into the next day, and then the next, and then the next. Within two years, every night of the week boasted at least one performance, with a second or third often slotted in according to audience demand. Many began at one in the morning. Measuring just 18 by 30 feet, the space technically accommodated 40 patrons around its octagon-shaped tables—but extra spectators crammed in wherever they could, even dangling their legs from a perch on top of the cigarette machine.

Poetry readings morphed into theatrical readings—first, classic works in the public domain or pirated one-act plays from big name writers. Admission was virtually free, with most customers spending just a dollar on coffee or pastries. But the bill of fare shifted, and by 1963, almost every performance at the Cino was from a brand-new script, with some 250 performances over nine years.

Some of these were exceptional works of literature. Others were not. Cino seldom read scripts ahead of their production, and tended to go with his gut on whether he was, for instance, fond of the playwright, or wanted to support their work. The output, therefore, was a kaleidoscope of talent, with the occasional bum note. These, Patrick writes, were “plays without concern for profit, publicity, propaganda, posterity, propriety, prana, or particular esthetic principles. It was an asylum for rejects.”

It was also highly illegal. According to city law at the time, venues that wanted to put on performances required both a liquor and cabaret license. The Cino had neither. Instead, Cino paid off cops however he could, sometimes resorting to sexual favors at the back of the room or calling on his rumored Mafia connections. Nonetheless, the Cino’s conservative Italian-American neighbors wasted no time in calling the NYPD whenever they could, likely due to the vibrant clientele, many of whom were gay, bohemian, people of color, or all three.

The financial penalties were constant, but the plays and the café limped on, mostly due to the fact that Cino, and his employees, took no pay. While other cafés and bars in the area were forced to curtail their performances due to mounting fines, the Cino’s cost were so low that they could often afford to pay their dues. Late into the night, a band of what Patrick describes as fellow “temple slaves” served food and drinks or washed dishes, returning to their day jobs in the morning. “If they sought anything in return,” writes the theater critic Stephen J. Bottoms in Playing Underground, “it was only the opportunity to participate in the new plays that were constantly being scheduled for production.”

As the crackdowns continued, and the Cino’s reputation for homosexuality became more widespread, its front windows were covered with posters to hide the spectacle within. These advertisements were often for the plays themselves—but disguised to look like abstract art, with intentionally coded lettering to avoid attracting the attention of passing policemen. Words might be upside down, or back-to-front. Often, the time and date was obscured.

These were the work of the artist Kenny Burgess, who moonlighted as the café’s dishwasher. One of these posters, for Lanford Wilson’s 1964 work The Madness of Lady Bright, is currently on display at the New York Public Library as part of the exhibition on counter-culture You Say You Want a Revolution: Remembering the 60s. Caffe Cino, writes curator Isaac Gewirtz, was a home of “first-class alternative theater,” and “a refuge for gay men at a time when gay bars were illegal.”

In a time before Stonewall, Caffe Cino was a haven for the city’s gay theatrical community. It was illegal at that time to depict homosexuality on stage, but the Cino flouted these rules as confidently as it did the city’s cabaret laws. Plays were almost always by gay men—Doric Wilson, Lanford Wilson, Robert Patrick—and often about them, too: The Madness of Lady Bright, Now She Dances, The Haunted Host, even Dames at Sea. “That was so exceptional,” Patrick says, “that it rather stands out in the history of the Cino.” Sometimes this edged into pantomime: In Return to Caffe Cino, the actor Dan Leach describes how his character “realizes his homosexuality, flits into the audience, flings himself onto the lap of the straightest-looking guy visible, and, running his hand through the unsuspecting guy’s hair, commences a seduction. That we didn’t get punched or walked out on or arrested is a testament to either the liberality of the times or the certain shock and seduction of the piece.” Or, perhaps, both.

Yes, Patrick says, there were gay spaces elsewhere in the city—“hinty, minty little nightclubs, grubby bathhouses”—where men would cruise. “But that’s all they were for, was to go and be gay. At the Cino, being gay was just part of life,” he says. Its patrons and performers could be themselves, and its proprietor was totally permissive. “For Joe,” the playwright Robert Heide remembered in the short documentary In the Life, “the doors were always open: Do your own thing, do what you have to do, do what you want to do.” Lanford Wilson cited “the incredible freedom of being able to be yourself in that place … You could do just anything and it made me want to experiment like crazy.” Off-Off Broadway provided artistic freedoms that could be found nowhere else in the city.

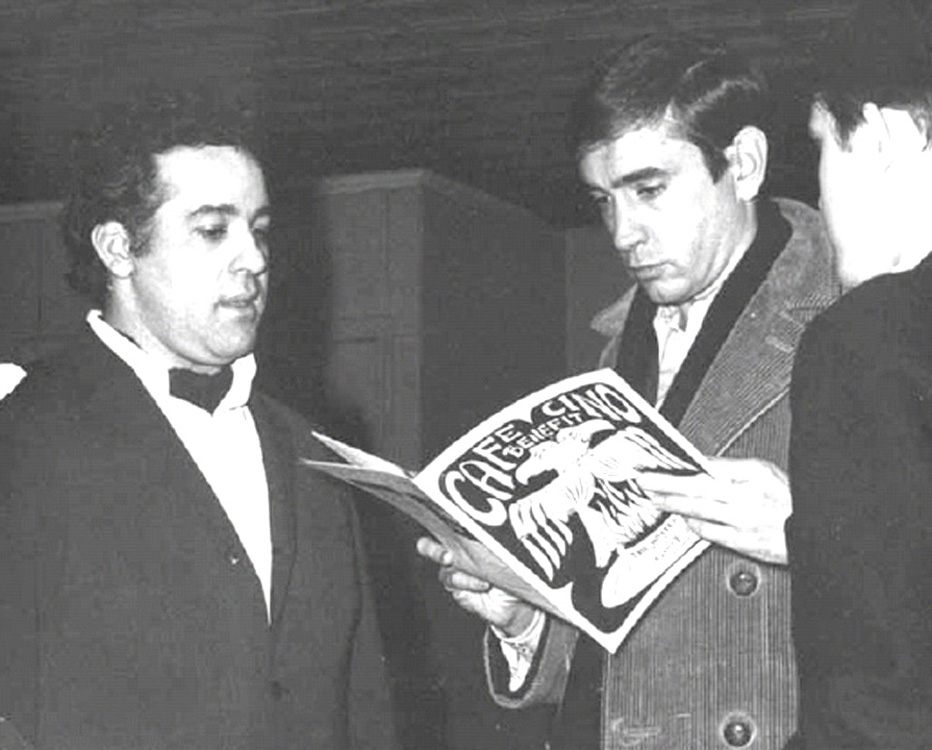

The Cino had as many ups as it did downs. When The Madness of Lady Bright became a breakthrough hit in 1964 and made its way onto Off-Broadway, the Cino’s popularity started to seep out of its postered windows and, very slowly, into the mainstream. In March 1965, the Cino caught fire, with its interior destroyed and the café closed for several months. Officially, it was a gas leak; unofficially, many believed it to be the deliberate action of Cino’s lover, John Torrey. Benefits funded a rebuild, and it reopened a few months later. The following year, the musical Dames at Sea had a 12-week run and was a runaway success.

In early 1967, nine years after it had opened, the Cino made its way into the New York Times, which described its “layers of avante-garde posters plastered collage-fashion on the walls and enough twinkling lights strung around the ceiling to decorate a forest of psychedelic Christmas trees.” The Cino, the Times said, had good hot chocolate “and equally interesting plays.”

But behind the scenes, all was not well. The success of Dames had drawn increasingly famous and ambitious drop-ins—Edward Albee, Bob Dylan, Andy Warhol—and with them, increasingly potent drugs. (“Drugs we’d never even smelled before,” says Patrick.) Narcotics had always been a feature of the Cino, but the quantity was unprecedented: Patrick remembers sweeping away piles of hypodermic syringes.

The pace grew more and more frenzied, and Cino’s own drug use increased accordingly. Then, a tragedy: Cino’s lover, the electrical engineer Torrey, was killed, ostensibly in an electrical accident, while working in New England in January 1967. Cino was distraught, believing it to be suicide, and took still more drugs. As the Cino entered a golden era of some of its best plays, its owner was foundering.

Accounts of the night of Thursday, March 30, 1967, differ. Patrick tells it thus: “One night some people who loved Joe, and whose idea of showing love was to give somebody drugs, without knowing that each other were doing it, dropped some particularly strong drugs in Joe’s drink.” Angelo Lovullo, his childhood friend, remembered him taking LSD that night, despite promising a few weeks earlier that he would stop. Either way, just before dawn on Friday morning, Cino came back to the café alone. There, he took a knife and stabbed himself repeatedly. He died three days later. Writing in the Village Voice that week, the theater critic Michael Smith described his death as “unthinkable, because he was always a creator of life.”

For almost a year, the staff of Cino continued without him as best they could. Patrick remembers a surreal day spent stenciling fleurs-de-lis over the bloodstains on the floor of the Cino with Wilson, as the radio broadcast coverage of the Oscars. The actor and playwright Charles Stanley, assisted by Michael Smith, did his best to keep it going—in late July 1967, he told the Times that Cino’s family had understood that “there was something precious to a good many people here … So far, we are doing alright.” But it was a struggle for them all, says Patrick, with accumulating back debts and intense scrutiny from city authorities. Not quite a decade after it had first opened, in March 1968, the Cino closed its doors for the last time. “Finally,” he says, “it was too much of a stretch.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook