Is the End Coming for a Problematic California Grade School Tradition?

The mission model project has long glossed over the brutal treatment of Native Americans.

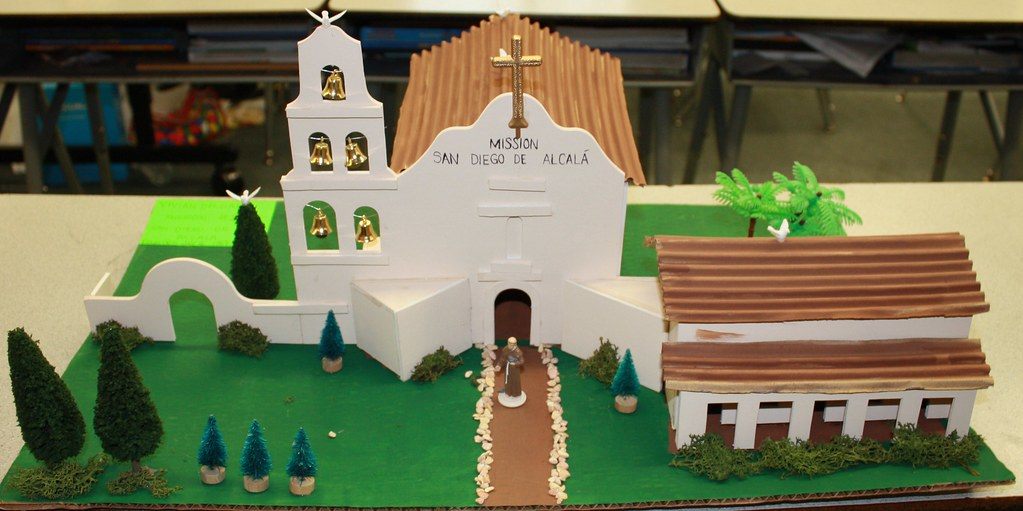

In 2004, Dash Turner was in the fourth grade, and had reached an important milestone in his California public school education. His class was studying the mission period, when Spanish priests attempted to convert California Indians to Catholicism. And that meant, for the fourth grade at Sierra View Elementary in Chico, and schools across the state, that it was mission model time. In the 18th and 19th centuries, these missions were built out of brick and adobe, by enslaved or conscripted Native Americans. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the missions were built out of sugar cubes or cereal boxes or prefab kits, by kids and helicopter parents. It was an arts-and-crafts distillation of a couple of centuries of conflict, conquest, and slaughter.

Unlike most children asked to make one of these dioramas, Turner is Native American. His teacher must have realized the pitfalls of the project for the only Native kid in class. It helped that Turner’s mother—in his words, a “four-foot-eight, ferocious Native American woman”—had a history of making sure teachers allowed her children to celebrate their heritage. So while every other kid in the class built a white mission, Turner, an enrolled member of the Yurok Tribe, and his partner, the only black student in the class, built a Yurok village, complete with sand collected from his family’s ancestral beach in Klamath, California, and fake moss from a craft store.

Mission models have been an institution in California’s state curriculum since the 1960s. Ask anyone who was once a fourth-grader in California: They probably built one. While the kids (besides Turner) probably didn’t know any better, the state should have. Since the 1960s, indigenous and Chicanx education activists have spoken out against the myth of the California mission—with generous padres and submissive Native Americans—that the model projects embody.

It wasn’t until 2017, after decades of activism, that the state released a new K–12 curriculum that dropped the mission project as a recommended teaching tool. The new framework pushes for lesson plans that focus more on the everyday life at the mission for California Indians and priests. Ideally this would capture more of the harm done to indigenous culture, but it is at least symbolic of a wider view of history.

Despite the new framework, it’s clear, from tweets from teachers to kits for sale online, that mission models are still being made in schools across California. It is hard to move on from a tradition that has lasted over half a century, let alone one that many adults today remember fondly.

Between 1769 and 1823, Franciscan missionaries began to establish an archipelago of 21 missions along the California coast, from San Diego to San Francisco, under orders from King Carlos III of Spain, according to anthropologist Elizabeth Kryder-Reid’s “Crafting the Past: Mission Models and the Curation of California Heritage,” in the journal Heritage & Society. At the head of this party was Junípero Serra, who was canonized by Pope Francis in 2015 and still towers, literally, over a California freeway named for him.

The missions represented the Church’s best attempt to bring Catholicism—and Spanish dominion—to indigenous people, at any cost. For Native Californians, the missions became a place of unrelenting atrocity, according to journalist Elias Castillo, author of A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions. “What the missions did to the Indians was genocidal,” Castillo says, adding that Serra celebrated the deaths of Native Americans as a sign of more souls in heaven.

To build their missions, these emissaries turned to the local populations as a convenient source of forced labor. Native Americans lived under horrific conditions, rampant with disease, and were frequently punished by the padres, Castillo says. In one incident at Mission San Francisco Solano, friars used a hot iron to burn crosses into the foreheads of a group who had tried to escape. By the time the missions were sold off in 1833, approximately 62,000 California Indians had died under the purview of the Spanish priests.

By the second half of the 19th century, the missions had either fallen into disrepair or been converted to parish churches, Kryder-Reid writes. Before they crumbled entirely, parishioners, preservation groups, and the 1920 film The Mark of Zorro—shot among the ruins of Mission San Juan Capistrano—reinvigorated public interest and nostalgia around the structures, according to artist and critic Tizziana Maria Baldenebro’s architecture thesis “A Los Que Nos Ofenden,” an excerpt from the Spanish version of the Lord’s Prayer that translates to “Those Who Trespass Against Us.”

In the 1930s, the U.S. Department of the Interior commissioned a survey of the historic buildings, focusing on their architecture rather than impact, Kryder-Reid writes. One by one, the missions were restored and became prominent sites for tourism and field trips. The chain of bells that connected the missions along El Camino Real, and the architecture of the missions themselves, were repurposed into the logo and name of one of the country’s most popular fast food taco chains.

As the missions were glorified in life, they became icons of California pride in textbooks. These books said more about 20th-century white America than they did about actual California history, historian Zevi Gutfreund writes in his 2010 paper “Standing Up to Sugar Cubes: The Contest over Ethnic Identity in California’s Fourth-Grade Mission Curriculum,” in Southern California Quarterly. Accordingly, Serra began to be characterized as the state’s premier pioneer.

In 1961, conservative educator Max Rafferty was elected the superintendent of La Cañada School District in Los Angeles County, and became state superintendent the next year. He helped ensure that the state’s first U.S. history book of the civil rights era emphasized the generosity of the Spanish padres. In 1964, Rupert (Cahuilla) and Jeanette Costo (Cherokee) formed the American Indian Historical Society (AIHS), which worked to educate the public about Native American history. The AIHS pressured Rafferty, and the Costos were appointed to the California Curriculum Commission.

They made early gains, convincing one textbook publisher in 1966 to remove an image of two Native Americans scalping a white woman and asking that textbooks identify people by tribe and name, as opposed to simply referring to each as “an Indian,” Gutfreund writes. But over time their relationship with Rafferty and the Board of Education splintered.

In the 1970s, Mexican-American education activists Julian Nava and Rodolfo Acuña supported the traditional mission curriculum as representative of Latinx history in the state, Gutfreund writes. Nava, the first Latino elected to the Los Angeles School Board, argued that Spanish Catholic priests could be heroes to white people as well as Mexican Americans. Much of the Chicanx activist community disagreed and campaigned alongside Native activists.

In 1998, the Board of Education revised fourth-grade standards for teaching the mission period to include Native Americans, Mexicans, and Spaniards. The curriculum adopted neutral, apolitical language and allowed educators to interpret the standards as they liked. The building of models of missions had emerged on its own—it was never officially mandated—but had quietly become a tradition across the state.

In 1998 in Stockton, California, 10-year-old Tizziana Maria Baldenebro built a model of Mission San Juan Capistrano out of hot glue and sugar cubes. Her mother, who had emigrated from Colombia, was working as a janitor, so she couldn’t afford the $40 mission model kits other kids purchased from craft stores. “There was a clear hierarchy in terms of what was produced,” she says. “The sugar cubes were the third-best alternative,” after the kits and popsicle sticks. (Kits today are $29 on Amazon, and sugar cubes have fallen out of favor for the ants they attract.)

“The fourth grade focused so much on that mission model that it became a mini-industry,” says Gregg Castro, a member of the Salinan Tribe, whose ancestors are buried at Mission Santa Clara. The quality and design of mission models vary based on parents’ willingness or ability to get involved in making them. One parent in the wealthy suburb of Menlo Park, for example, once donated drums of plaster so every student could use real stucco in their models, Gutfreund writes.

In 2017, the California History Social Science Project (CHSSP), a statewide network of history educators headquartered at the University of California, Davis, released the updated framework for how history and social science should be taught in the state. “We have a greater responsibility to our citizens, especially Native Californians, and we have a greater responsibility to our children,” says Nancy McTygue, the executive director of CHSSP. “Nostalgia is just not a good enough reason to continue the mission project.”

“Building missions from sugar cubes or popsicle sticks does not help students understand the period and is offensive to many,” the guidelines read. “Instead, students should have access to multiple sources to help them understand the lives of different groups of people who lived in and around missions, so that students can place them in a comparative context. Missions were sites of conflict, conquest, and forced labor.”

But this is just a guide. “There’s nothing in the curriculum that can force a school or district to stop doing mission projects,” McTygue adds. “There’s nothing legally we can do to prevent that.”

Today, mission model–building continues, with some decidedly contemporary forms. In Walnut Valley Unified School District near Los Angeles, several elementary schools now ask students to build interactive models in the educational version of Minecraft, Patch reports. Another student in California recently made headlines for 3D-printing her model.

The problem may be that the truth of the mission era isn’t appropriate for tweens. “If you tell the full history of the missions, fourth-graders are going to have a screaming nightmare,” Castillo says. “Tenth-graders can handle the truth much better.” However, such a change would require action from the Board of Education, and no one expects that to happen.

So if mission history is to remain in the fourth grade, what is there to teach besides popsicle sticks? “You can’t give a fourth-grader a 400-page book called Murder State,” says Rose Borunda, from the education faculty at California State University, Sacramento. But she also notes that elementary-school children can, and do, learn about historical tragedy. “We might talk about what happened in Nazi Germany, but we don’t talk about what happens here.”

In 2014, Borunda and Castro founded the California Indian History Curriculum Coalition (CIHCC). (Castro is a member of the Salinan Tribe and Borunda is not California Indian but is indigenous to the Purepecha Tribe in Mexico.) Building off the earlier work of the Costos, they’re trying to reimagine how to teach fourth-graders their state’s history, according to Allison Herrera in High Country News. Instead of treating California Indians as a monolith, the CIHCC is working toward regionally specific curriculum. For example, children in Chico would learn about the Maidu Tribe and children in Lodi might learn about the Miwok Tribe. They’re also pushing for the curriculum to embrace 10,000 years of history, rather than focus on the mission period.

In 2016, the CIHCC released a resolution to “Repeal, Replace, and Reframe the 4th Grade Mission Project” to ensure future generations will not have to build the models, but it’s an uphill battle, with little time and few resources to train teachers in alternatives.

Most people I interviewed about their own elementary school experiences remember less about the history of the missions than they do about making them. “My only memory of the project itself is that the teachers implied we would cheat by buying a kit,” says Yasmin Adele Majeed, who built one as a fourth-grader in Sunnyvale. “My understanding of the mission model as a fucked-up way to teach the mission period only came in college.”

Turner, the Native American student from Chico, looks back fondly on his own version of the project. “The other kids were building these boring stucco missions, and Natalie [his partner] and I made an absolutely gorgeous Yurok village,” he says, adding that he grew up far from his tribe’s reservation, so he enjoyed being able to celebrate it in school.

The resistance engineered by Turner and his determined mother is a strategy for other families, too. In 2017, Cutcha Risling Baldy, a professor of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University, Hupa, Yurok and Karuk, and an enrolled member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe, helped her daughter build a model of Mission San Diego—but hers incorporated the 1775 revolt in which the Kumeyaay people burned the mission to the ground, according to a post on her blog. The model looks apocalyptic, but the original plan was even more extreme: to actually set it on fire.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook