Is This the End of the Cannonball Run?

For a century, a “fraternity of lunatics”—inspired by a driving pioneer and a 1980s movie—has raced across the United States. Is the newest, pandemic-era record unbreakable?

On a May day in 2020, a nondescript sedan set out from the Red Ball Garage in Manhattan, its driver determined to take back a piece of history.

Departing shortly before 6 p.m., the silver Audi S6 should have encountered rush hour—but the world had closed down due to COVID-19. The sedan hit one stoplight on East 31st Street and was through the Lincoln Tunnel into New Jersey in six minutes, the start of a daylong, cross-country odyssey.

Drivers Arne Toman and Doug Tabbutt were out to reclaim the Cannonball Run record which they’d set the previous November, racing from New York to Southern California in 27 hours, 35 minutes. It had been broken just a few months later. Now, on the expansive flat, straight—and empty, thanks to the pandemic—highways of the Midwest, the Audi was able to reach 175 miles per hour in spots. Toman and Tabbutt pulled into the Portofino Inn in Redondo Beach, California, 25 hours and 39 minutes after their departure from New York City.

The race route is not a particularly well-mapped one—how the drivers got from point A to point B was their concern—but they were participants in a contest that dates back more than a century, when the smooth, paved highways they used were nothing but a dream. Erwin “Cannon Ball” Baker, the race’s namesake, was the first of dozens who have engaged in the battle of wits, skill, and endurance. Toman and Tabbutt were just the latest in a long line of record breakers—and heirs to the scofflaw culture that have continued the race, hidden from public view, for years.

“It just seems like the most American thing you can do,” Tabbutt says. “Drive across the country as fast as you want.”

For Cannon Ball Baker, “fast” wasn’t that fast. In 1914, the factory worker-turned-vaudevillian-turned racer crossed the country in 11 and a half days on what was believed to be the first transcontinental trip on a motorcycle. (That itself was speedy; five years later, a U.S. military convoy crossed the country on the new Lincoln Highway. It took 58 days.) By 1933, thanks to advances in roads and automotive technology, Baker was able to cross the country by car in a supercharged Graham-Paige Blue Streak in a little more than two days—53 hours and five minutes.

Baker remained an influential figure in the racing world for decades; one of his last roles was as the commissioner of a new stock car racing circuit: NASCAR. He died in 1960, but when another iconoclast was looking for a namesake for a race, he looked to Cannon Ball Baker.

As a writer and editor at Car & Driver, Brock Yates tilted at windmills, railing against the “Grosse Pointe Myopians” that were stagnating the American auto industry and the specter of highway speed limits. Yates was an advocate for graduated driver’s licenses, which would grant different privileges for different skill sets. One size didn’t fit all, he believed. and more intensive training would allow the United States to create high-speed roads like Germany’s Autobahn.

”This was when people took driving seriously,” says his son, Brock Jr. “Good drivers could traverse long distances at high speed safely.”

Yates was determined to prove it, so on a drizzly May day in 1971, he and Steve Smith set out in a Dodge van they named Moon Trash II and accented with a wing that probably did nothing to cut down on wind resistance. Brock Jr., 14 at the time, was brought along as navigator, runner for snacks during fuel stops and lookout to try to spot police cars that could potentially pull them over. They set out from the Red Ball Garage—so chosen because it was open 24 hours—and completed the race in 40 hours and 51 minutes, ending at the Portofino, which was already establishing itself as a haven for racers.

Moon Trash II was one of eight entrants six months later in the Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash, set up by Yates. Yates and Dan Gurney won in a Ferrari, shaving the record down to 35 hours, 54 minutes. Other races were held in 1972, 1975, and 1979, the last two in protest of the new national speed limit on interstate highways—55 miles per hour. After that, Yates stopped holding races, fearing that it had grown too big to fly under the radar or be completed safely.

“Brock said, ‘No, this is getting stupid. People should not be going that fast on a public highway,’” Brock Jr. recalls.

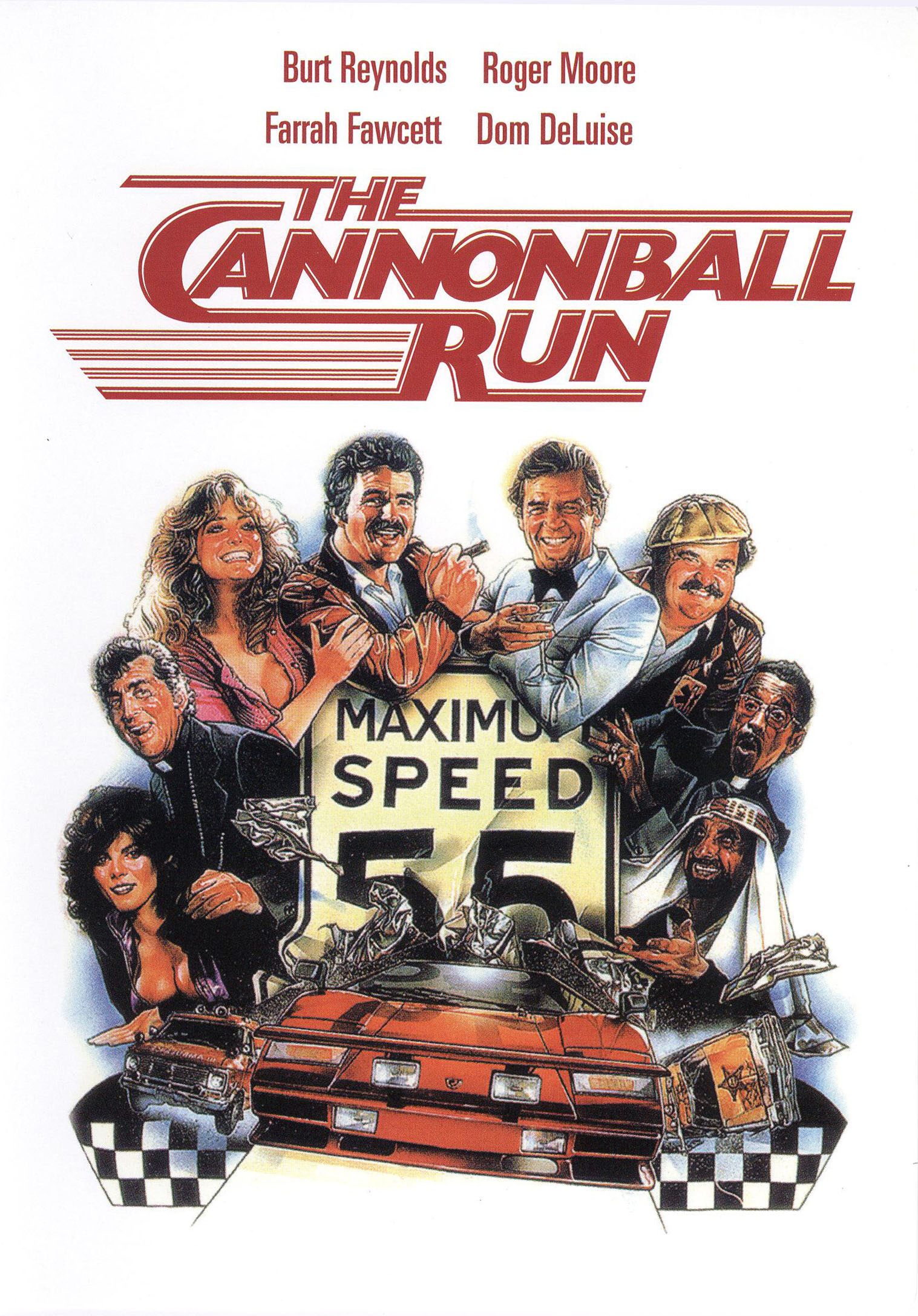

In the last race, in 1979, Yates partnered with stuntman-turned-director Hal Needham, driving another Dodge van, this one made to look like an ambulance. The story of the race fascinated Needham, who’d already directed Smokey and the Bandit, and he and Yates developed a script, which turned into the movie Cannonball Run. Originally intended as a vehicle for Steve McQueen–who passed away in 1980—it instead became a box office smash (if not a critical hit) for Burt Reynolds and an all-star cast. The 1981 movie then became a staple on weekend afternoon television. Among its viewers was the next generation of renegade cross-country racers.

The Cannonball Run died out, but cross-country races didn’t. There was the U.S. Express, the C2C Express, and the Lap Around America. As a child in Atlanta, Ed Bolian read of those exploits in old car magazines, and to him, “it was like the moon landing.”

“I just became fascinated,” he says. “Nobody had really advanced the record since 1983, and I didn’t think anyone would, with twice as many people and twice as many police on the road.”

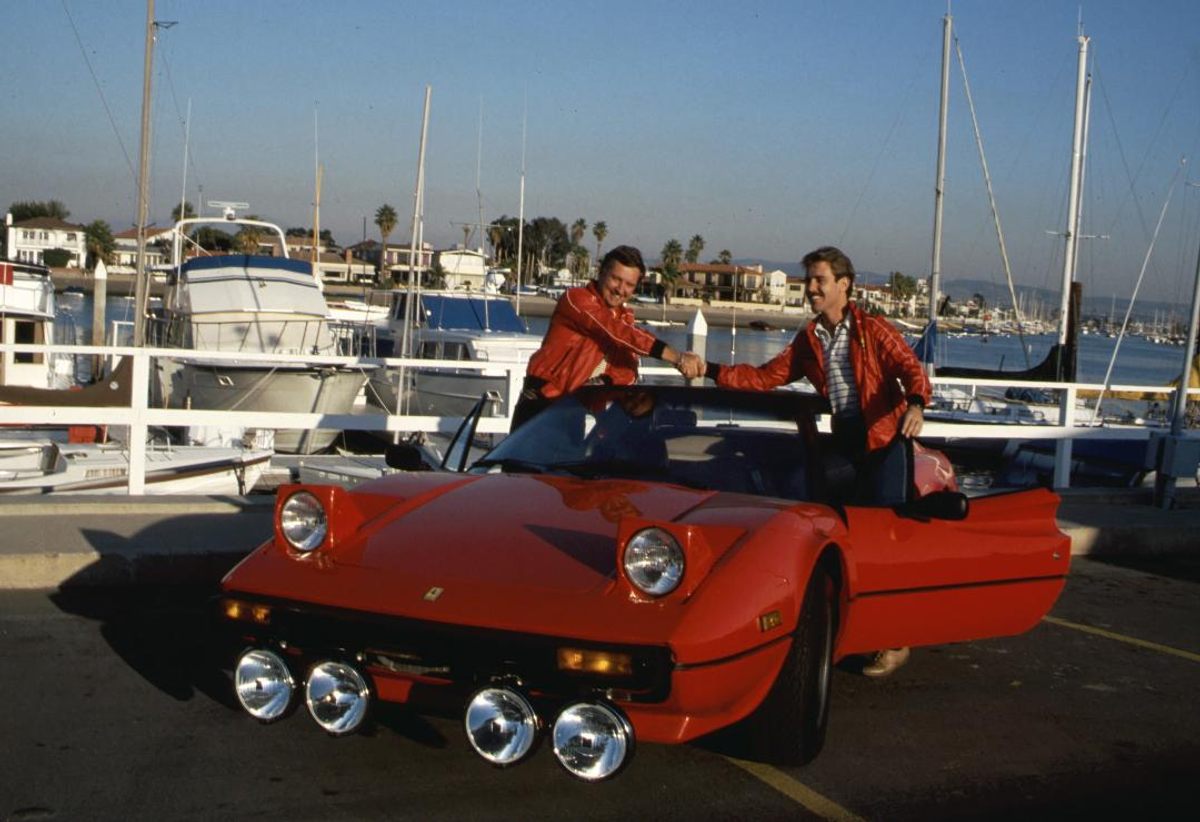

But he still wanted to be part of what was now known as the “fraternity of lunatics”—those who made the Cannonball Run. He and Dave Black* set out from the Red Ball Garage on October 19, 2013, in what he thought would be a “shakedown run,” the test before entering competition. Bolian and Black were driving a Mercedes CL 55 AMG, the type of German sedan engineered for the kind of high-speed driving necessary for a Cannonball Run, but unobtrusive enough to blend in.

“If you tried to do it in a red Ferrari, you probably wouldn’t get out of New Jersey,” Toman says.

Bolian and Black set a new record, making the run in 28 hours, 50 minutes. “I didn’t do it to be famous,” Bolian says. “It was a personal goal, like climbing Everest because it was there. I hoped for one good article that I could put on the wall in my office, but it really blew up.”

Bolian competed in other road races, where he eventually crossed paths with Arne Toman, who started to get the itch to do a Cannonball Run himself. The appeal to Toman wasn’t racing as much as building the car, which would need extra fuel tanks to cut down on stops, as well as technology to evade being busted for speeding. “It’s the Super Bowl of police countermeasures,” he says. His first Cannonball car was an 800 horsepower 2015 Mercedes E63 AMG, which he used to break the record in 2019.

Then, the following March, the world shut down, and the nation’s empty highways looked enticing to potential Cannonballers. Bolian said the record was broken 12 times during the early months of the pandemic. “It was just an unimaginable set of circumstances,” he says.

Toman wanted to recapture the record. But on April 4, 2020, as he was pulled to the side of the road in Illinois, as a spotter for a Volkswagen Passat making its own Cannonball run, he watched his Mercedes get hit by a truck. He escaped injury, but he would need a new car to make another run. Toman found an Audi. “The first time I saw one of those, I said, ‘It looks like a Ford Taurus.” And he used that to his advantage, putting on a new front end that drove home the comparison. And it worked. He had a small army of spotters and scouts helping him break the record —many of whom didn’t recognize him as he whizzed past, thinking it was an unmarked police cruiser.

Toman reclaimed the record, and as the world opened back up, the roads became just as clogged as before. Traffic may mark the end of the century-long tradition of daring and dangerous one-upmanship: “I think most of the major runs are over with,” Yates says now.

Bolian, who’s married with a child and mostly retired from road racing, sees the 25:39 mark standing for a long time. “I don’t think it’ll get any faster, because I don’t think the world will turn the highways off ever again,” he says. “At least, I hope not.”

*Correction: An earlier version misidentified one of the drivers who broke the Cannonball Run record in 2013. They were Ed Bolian and Dave Black.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook