What Should You Do With a Captured Nazi Flag?

During WWII, American soldiers brought the flags home as a remembrance. Now, family members and historians must decide what should become of them.

When Jaqueline Antonovich first saw the flag, her body flooded with fear. She would recognize that flash of red anywhere. Antonovich is a historian at Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania, and she had recently purchased a mid-1800s-era farmhouse in Allentown. Antonovich’s new house kept offering her small gifts from its long history—an antique glass baby bottle, an old trunk. And the flag, folded in an army-green metal box behind the kitchen’s wood-burning stove.

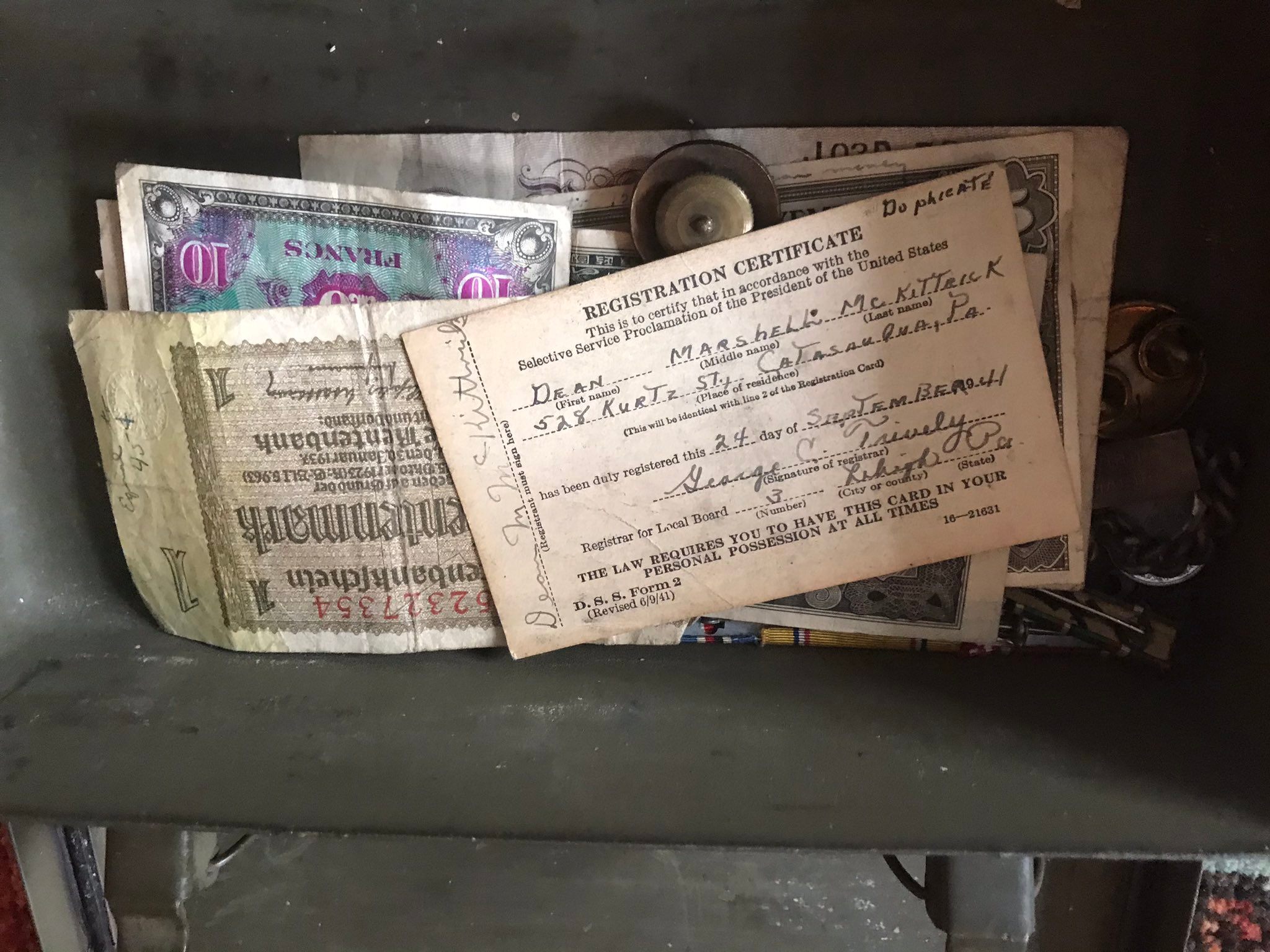

She found the box while dusting, a few days before Christmas 2020. She brushed away grime to reveal the words “Gas Casualty First Aid.” Antonovich, who is also co-founder of the digital history of medicine journal Nursing Clio, figured it was a World War II medic box, but when she opened it, she found dog tags and a registration card—and the telltale crimson.

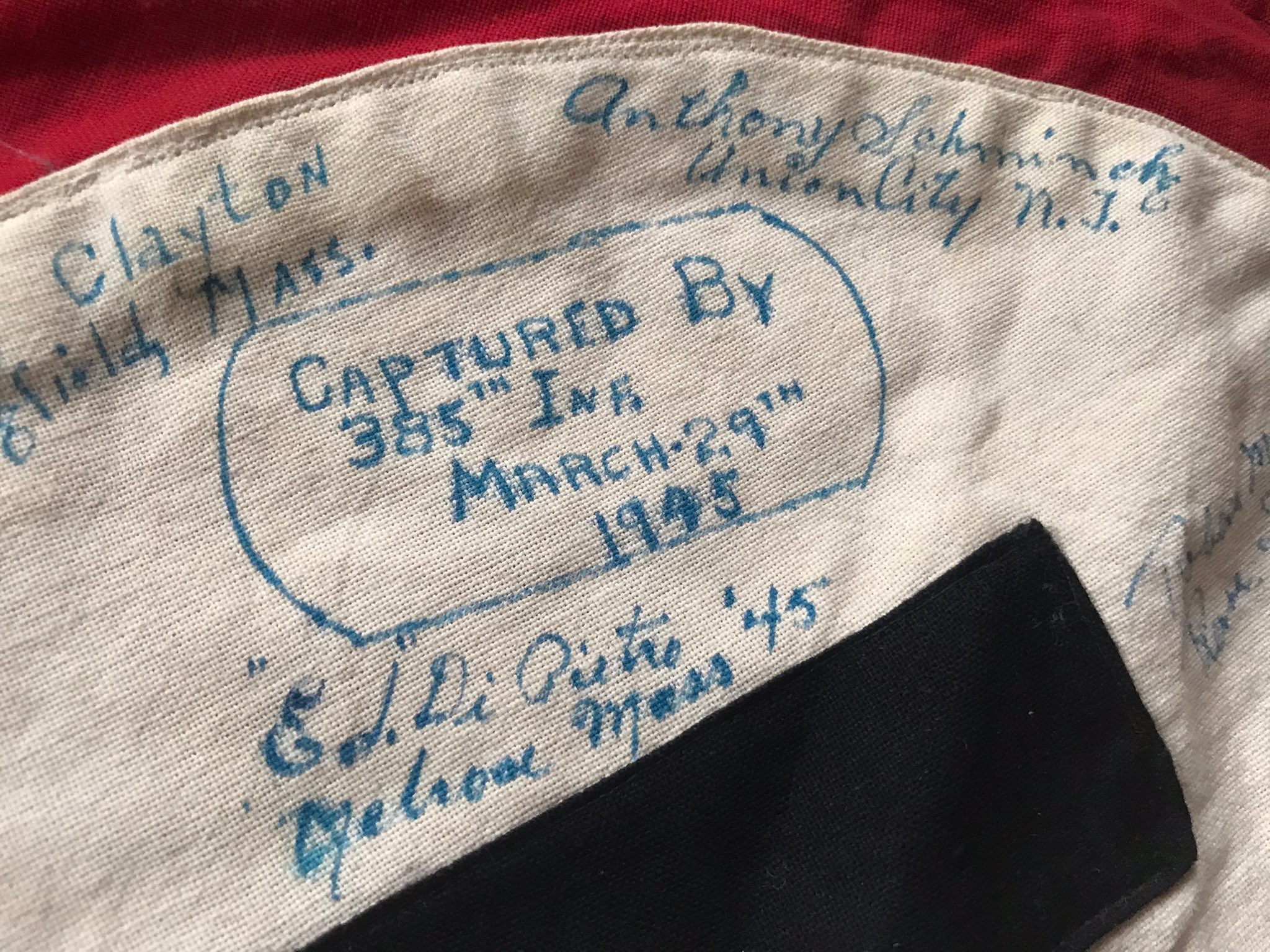

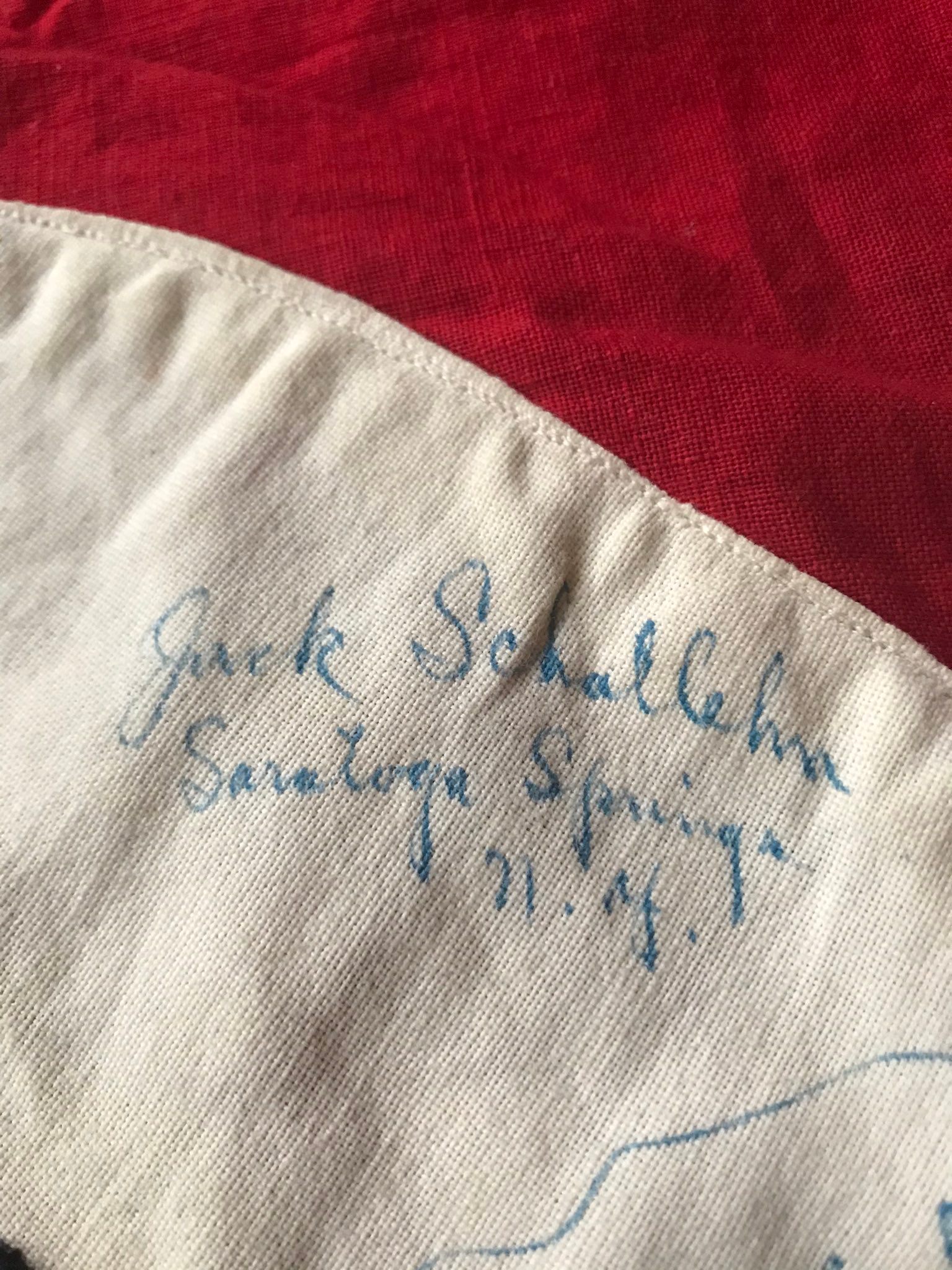

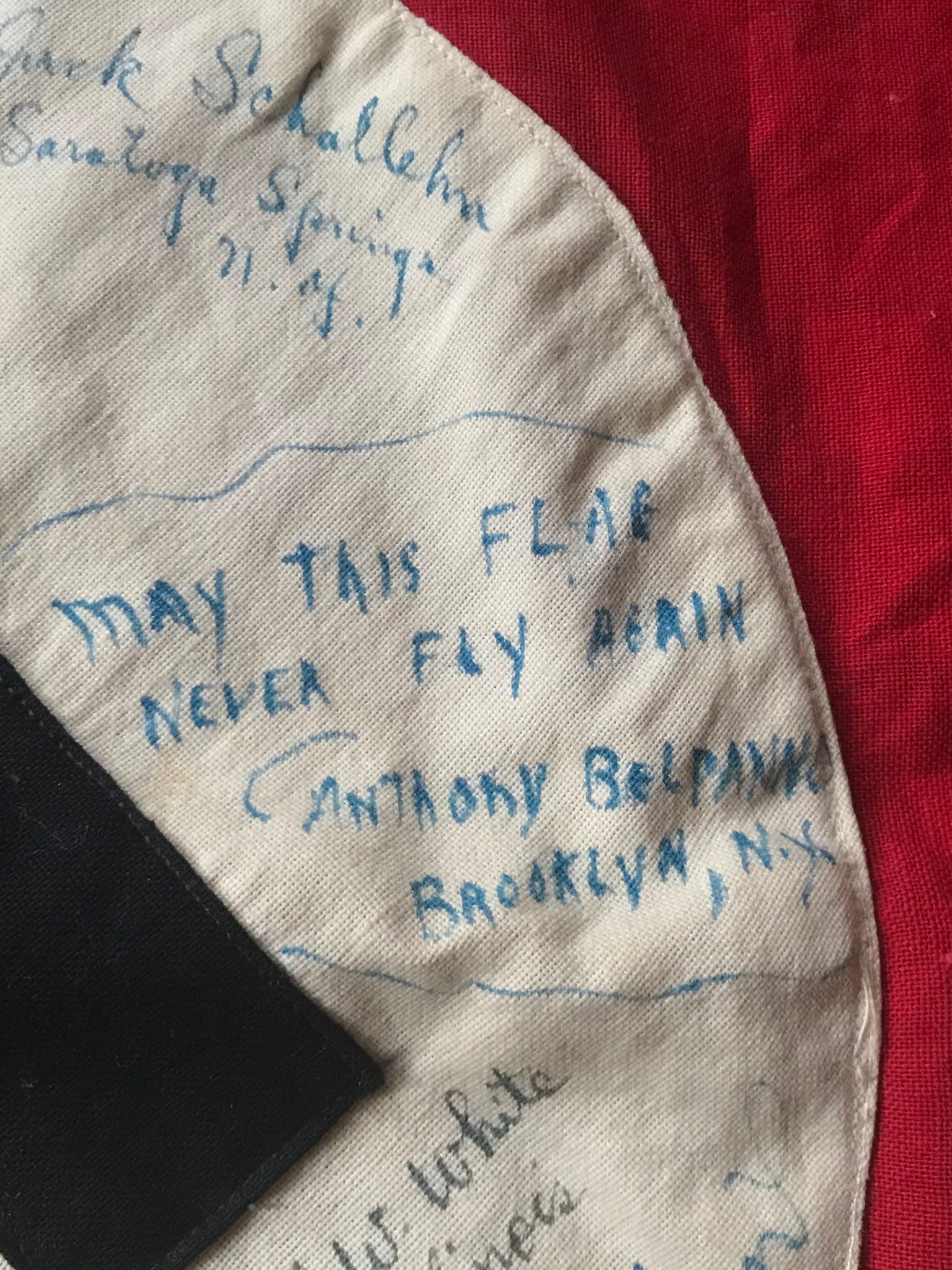

At first, the find was alarming. “I got really scared for half a second,” Antonovich says. But the flag wasn’t part of a racist collection: Upon closer look, Antonovich found that it was a memory of the defeat of the Nazi regime, signed by the American World War II veterans who had captured the flag in Europe. Among the names and hometowns of soldiers—Jack Schallehn from Saratoga Springs, New York; Anthony Belpanno, from Brooklyn—was a note, “Captured by 385th Infantry, March 29th, 1945.” The flag also bore a proclamation from Belpanno: “May this flag never fly again.”

Antonovich was floored. “I may have teared up,” she says. She posted news of the find to Twitter, sharing images of the signatures but not of the swastika itself, out of sensitivity to the violence of the symbol. Her followers were equally fascinated. Yet when Anotonovich’s giddiness at her historical find faded, she was left with a perplexing question: What should she do with it?

Anotonovich’s dilemma is not as rare as it may seem. According to Robert Citino, executive director of the Institute for the Study of War and Democracy at the National WWII Museum, signed Nazi flags are surprisingly common. “There’s a lot of those in the possession of Americans of a certain generation,” says Citino, whose father was a World War II veteran. “What it shows is the pride they took in their service and the pride they took in bringing down Hitler.”

Many Americans who served were young, and the war was their first and often only opportunity to see the world. For many of them, captured Nazi flags, weapons, and other objects became a mix of souvenir, trophy, and traumatic remembrance. Maggie Radd, vice president of collections and exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage - A Living Memorial to the Holocaust,* says that some Allied commanding officers routinely stripped captured Nazis of their weapons and regalia, and let junior officers take these objects home.

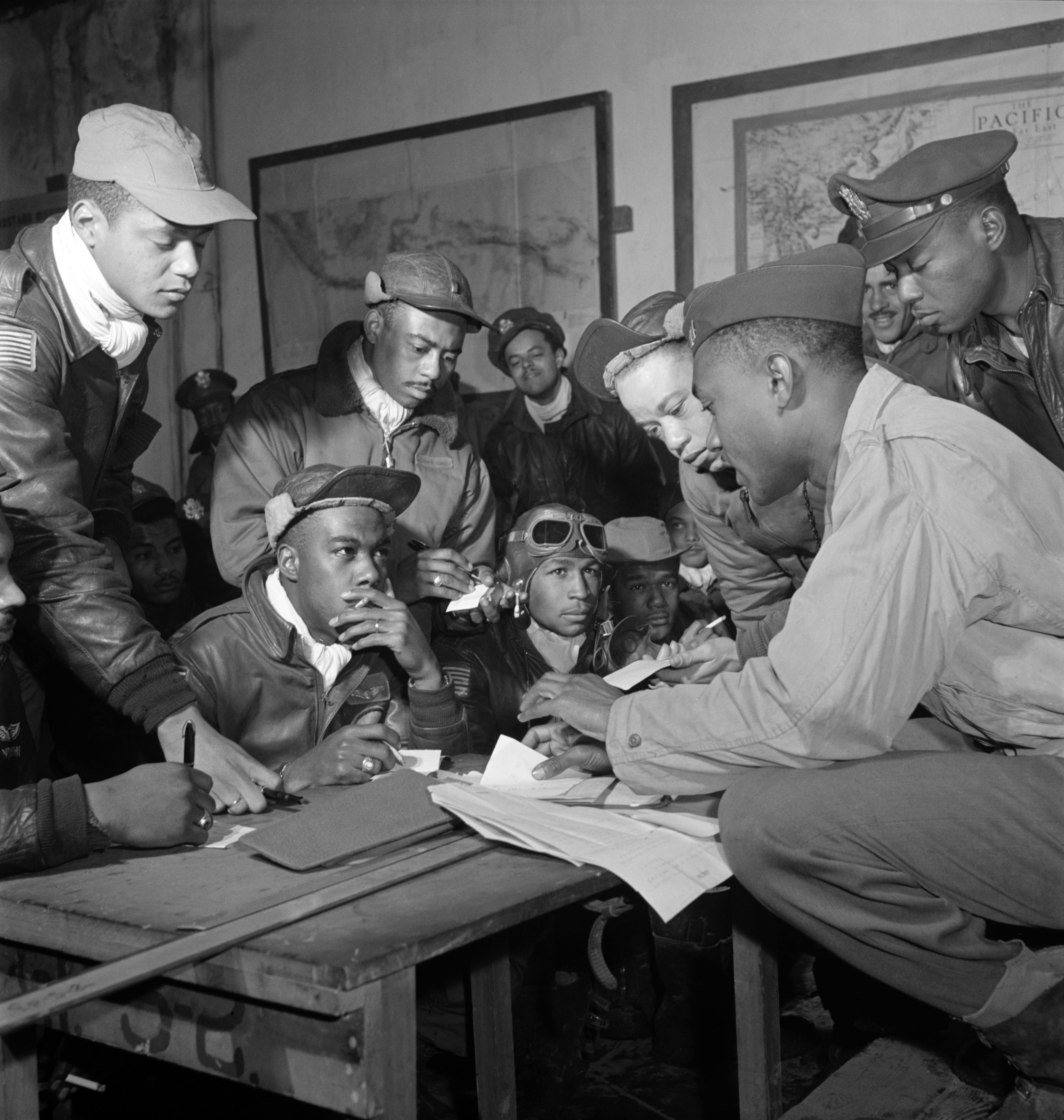

Captured objects carried different meanings depending on soldiers’ backgrounds. For Black soldiers, who were fighting a double war against Jim Crow at home and in the military, as well as fascism in Europe, Nazi symbolism may have been particularly loaded, says Matthew Delmont, a professor of history at Dartmouth College. “They helped to destroy an extremely racist ideology,” even while fighting in segregated units, he says. “And then, for so many of the Black troops, they just came home and kept fighting.”

Many of these artifacts wound up in museum collections—Citino estimates that, in total, the National World War II Museum in New Orleans has between 25 and 30 signed, captured Nazi flags in its collection—while others stayed with soldiers’ families. Zachary Levine, director of archival and curatorial affairs for the National Institute for Holocaust Documentation, says the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum receives emails from people wanting to donate a family member’s object every day. In Citino’s career teaching college courses on World War II, at least once a semester, he says, a student would bring an ancestor’s captured Nazi flag or even an SS dagger.

For family members, these objects can be a treasured reminder of a loved one’s time in the military. When Sheri Schrade read a news article about Antonovich’s find, “It just blew my mind,” she says. “I couldn’t believe it.” Schrade’s uncle, Jack Schallehn, had signed the flag.

Schrade remembered her Uncle Jack as a handsome man who lived in New York City with a roommate and occasionally came to visit her hometown, Saratoga Springs, to go to the racetrack. He had served as a medic in Europe; two of his brothers had also served in World War II. One of his brothers, Schrade’s Uncle Leonard, had been shot down over France, parachuted out of his plane, found refuge with a French family, and lived to return to France for the 50-year reunion of D-Day.

As meaningful as the signed flags can be, it’s impossible to separate them from the swastika’s meaning as a symbol of anti-Semitism and genocide. “It felt weird that I was in that house for almost three months, and it was in the house the whole time,” says Antonovich.

Curators and historians who routinely deal with Nazi objects echo the sentiment. Levine, who is Jewish and whose grandparents survived the war in Central Asia, says that walking among his museum’s collections is a visceral experience. Once, he was standing next to an IBM counting machine used to calculate numbers of murdered Jewish people, when “I was suddenly overwhelmed and chilled to my core because of the proximity to these materials,” he says. Radd says that, while handling artifacts of genocide, museum staff often have to take mental health breaks.

“I’m a historian; I consider myself educated; I write books with gigantic footnotes,” Citino says—but even with a deep understanding of the historical context surrounding it, he’d be unsettled by a Nazi flag. Though Citino says U.S. soldiers’ signatures transform the historical meaning of the flag—“it became American when they put their signatures on it”— that doesn’t mean he wants to live alongside one. “If I had a swastika flag up in the attic, and I just found it there, I wouldn’t want to keep it. No way I’d want to keep it,” he says.

Yet donating the flags can be surprisingly difficult. The Nazis were prolific flag-makers; during the Third Reich, they made millions of them. After the fall of the regime, an untold number of the flags remained. Many were in Europe; some were destroyed; some were kept by remaining Nazi sympathizers or, later, fell into the hands of neo-Nazis. Others traveled to the United States in the rucksacks of American soldiers. As a result, there are now so many World War II-era Nazi flags in the United States, many museums won’t take them.

In 2016, Jessica Goldstein faced a dilemma similar to Antonovich’s: What should she do with the Nazi flag in her parents’ attic?

Unlike Antonovich’s surprise find, Goldstein, who wrote about her experience for The New York Times, had long been aware of the captured flag. “My grandpa, my mom’s dad, was in the Army during World War II, and he saved everything,” Goldstein explains. He entrusted his relics to Goldstein’s mother shortly before he died. The cache included his dog tags, his discharge papers, and—folded in a two-gallon Ziploc bag in Goldstein’s mother’s attic—a captured Nazi flag, signed by the soldiers in his battalion.

Goldstein remembers first seeing the flag as a child. “The first time I saw it, it was bigger than I was,” she says. “It was the kind of thing that once you see it, you never stop thinking about.”

When Goldstein was in college, she interviewed her grandfather about his service. In 1945, he said, as the Nazi regime was crumbling, her 21-year-old grandfather and his fellow soldiers in the 460th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion traveled to Berghof, Hitler’s country estate in the Bavarian Alps. By the time they reached their destination, the war was over; the fortress was a shell of looted luxury. “They took everything, which I just love thinking about,” says Goldstein. “They unscrewed the lightbulbs. They raided the liquor cabinet.” And they took, and signed, the flag. Most of the soldiers who signed the flag were in their late teens and early twenties; looking at it years later, says Goldstein, felt like reading a yearbook.

Goldstein’s grandfather died in the summer of 2015. The United States was gearing up to elect Donald Trump. Overt displays of anti-Semitism and white supremacy were in a moment of ribald resurgence.

As racists increasingly incorporated Nazi iconography into 21st-century symbolism—swastikas and other Nazi symbols appeared at the deadly Unite the Right valley in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017—Goldstein couldn’t shake the thought of the flag in her family’s attic. “I just thought about it all the time,” she says. On one hand, she said, the flag, and others like it, “Are so obviously artifacts of evil.” It scared her to think that Hitler had likely stood in the same room as an object that was now in her mother’s house. On the other hand, she says, “The signatures are so obviously radiating triumph, and victory, and relief, and also youth.” Goldstein’s ambivalence around the object was intense. “It feels like the war in a microcosm.”

After Trump’s election, Goldstein decided it was time to do something about the flag. With her family’s blessing, she began researching museums that might take it. It was a much more difficult proposition than she thought. Due to the glut of artifacts Citino describes, most museums she researched were closed to donations of Nazi flags, with one exception: They would take flags signed by American soldiers. Goldstein ultimately ended up donating the flag to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

Antonovich had a particularly fraught time deciding what to do with the signed flag she found in her fireplace. She knew she didn’t want to keep it in her house, but she was unsure of an alternative: Keep it in her office as a teaching tool? Donate it to a museum? To complicate matters, unlike Goldstein, who associated the object with her grandfather’s service, Antonovich initially had no idea who Dean McKittrick—whose dog tags she found—was.

Citizen historians helped her solve the mystery. Within days of posting a thread about her find to Twitter, relatives of the flag’s signers began to get in touch. A local Catasauqua town council member saw one of Antonovich’s social media posts, and sent it to Brian McKittrick, who is also on the town council. Brian recognized his uncle’s name, and got in touch with Antonovich.

Dean McKittrick was one of five brothers and four sisters who grew up in Catasauqua. A couple of the brothers served in the military; Dean served in World War II as a medic. When Dean and his fellow soldiers captured the flag in 1945, Brian McKittrick was about a year old. Brian remembers his uncle as a lineman for the local power company who showed up for family get-togethers but didn’t talk much about the military.

“I never saw the flag, I never saw the box,” Brian McKittrick says. “Some people—when the war was over, the war was over,” he adds. “I think they just really wanted to forget it and move on with their life.” He doesn’t think his uncle ever showed people the flag.

Dean McKittrick and his wife didn’t have children. When they died, their niece, Brian’s cousin, became executor of the estate. It was her house that Antonovich had bought, after the elderly niece and her husband moved out—and when Antonovich purchased the house, she became the legal owner of everything inside of it, including the flag.

When Antonovich called Brian McKittrick, he said he thought the flag belonged in a university or a museum. The daughter of the couple who had previously owned the house, Brian’s cousin, initially agreed. Antonovich, too, leaned toward donation.

Antonovich’s feelings were intensified when, on January 6, 2021, a couple weeks after she discovered the flag, white supremacists sporting Nazi and Confederate symbols stormed the U.S. Capitol. The confluence of the two symbols wasn’t coincidental. As more recent scholarship reveals, “Nazi Germany really did draw on the methods of Jim Crow segregation in the South, and the methods of Native American removal and genocide,” Delmont says. Reflecting this, in the lead-up to WWII, some Black activists and journalists condemned the stars and stripes as just as racist as the swastika. Yet even while witnessing the horror of genocide in Europe, many white servicemembers were unable or unwilling to make the connection between Nazi ideology and American genocide and apartheid against Native and Black Americans. In several towns across Europe, white Southern U.S. troops flew the Confederate flag either alongside or instead of the American flag.

Antonovich has researched the role of doctors in the Ku Klux Klan, so the white supremacist and anti-Semitic symbolism of January 6 hit home—and deepened the dilemma about what to do with the flag. “I don’t think you can overlook the fascist impulse, or moment that we find ourselves in,” she says. She was haunted by the fear that, if she made the wrong choice, the flag may get lost and somehow find its way to someone who would fly it. In a museum, she figured, visitors could see the flag as a properly contextualized piece of history.

Antonovich had just begun to research potential institutions for donation when the daughter of the house’s previous owners, who was administering their legal affairs, got back in touch. She had seen the news coverage of the flag, and she asked for the family artifact back. (Through a liaison, she declined to comment for this story.) Antonovich was hesitant at first—she strongly felt the flag should end up in a museum. But she also wanted to respect family members’ wishes. She gave the family the flag.

If you find a WWII-era Nazi flag in your home, the museum professionals I spoke to suggest donating it. Radd advises first finding out as much as you can about where the object came from, since provenance is the most important factor in donation. Many museums, including the National WWII Museum, accept signed flags or flags with known historical significance. If your flag is unsigned, but you suspect it was captured by an American soldier from the period, Citino suggests getting in touch with your local history or military museum, which might be more receptive to these donations than large national museums.

Why preserve a Nazi relic at all? After all, desecrating Nazi flags is an act of defiance as old as the Nazis themselves, and contemporary activists continue to destroy racist flags as a form of protest. Radd, however, sees museum preservation of Nazi objects as evidence of brutality past—and a warning for the future. “We have to look at this atrocious period of time. It can’t be denied,” she says. Brian McKittrick, whose uncle helped capture and sign the flag Antonovich found, agrees. “We like to forget, but we never can forget,” he says.

If a museum won’t take your object, however, you may want to destroy it. “A curator might say, ‘You know what, I’ve got to tell you, it’s not rare, it’s not valuable, it’s not particularly interesting to us, I’d just discard it,’” Citino concedes. If you choose to do that, he adds, “Throw it in the garbage and make sure it’s not on display in the garbage can.”

Antonovich, for her part, still isn’t sure if giving the flag back to the family, rather than directly to a museum, was the right move. “I don’t know what the answer is,” says Antonovich. But she does know that the meaning of historical objects isn’t just about the abstract bigger picture—it’s also about what these objects mean to the people whose lives and stories they are a part of. “History is full of messiness, and it’s full of people with differing needs and wants and ideologies,” says Antonovich. “There’s never a clear-cut answer.”

Except for this: Almost anything you could choose to do with a captured Nazi flag—donate it, discard it, or keep as an anti-Nazi family memory—is better than raising it. The young men who captured McKittrick’s flag left it to history with just one instruction: “May this flag never fly again.”

* Correction: An earlier version of this story referred to the National Museum of Jewish Heritage; the correct name of the institution is the Museum of Jewish Heritage - A Living Memorial to the Holocaust.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook