There Are People Who Pay Thousands for the Empty Pill Bottles of Dead Celebrities

Stars in question have included Elvis, Truman Capote, Michael Jackson, and Marilyn Monroe.

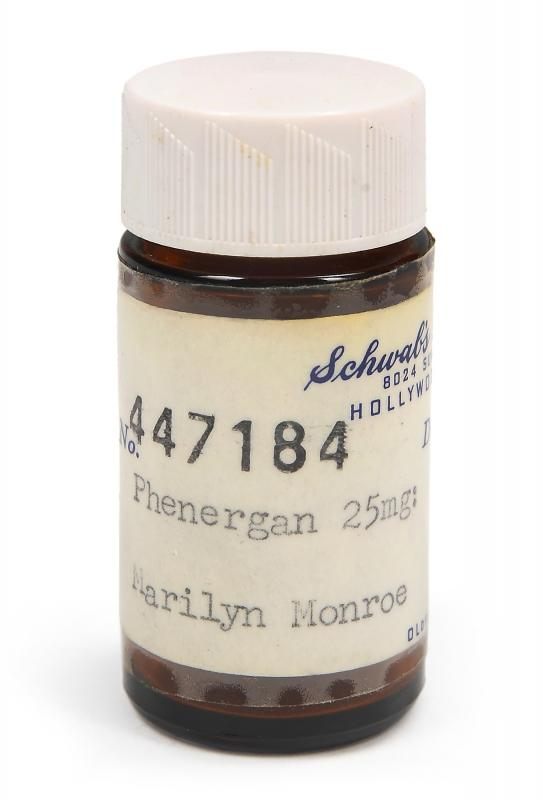

Deceased celebrities who grew too fond of prescription drugs left behind evidence of their habits, in the form of pharmacy bottles. These macabre artifacts now widely circulate at auction houses.

Fans collect the containers to better understand which chemicals coursed through the bloodstreams of the stars and in some cases ruined careers and lives.

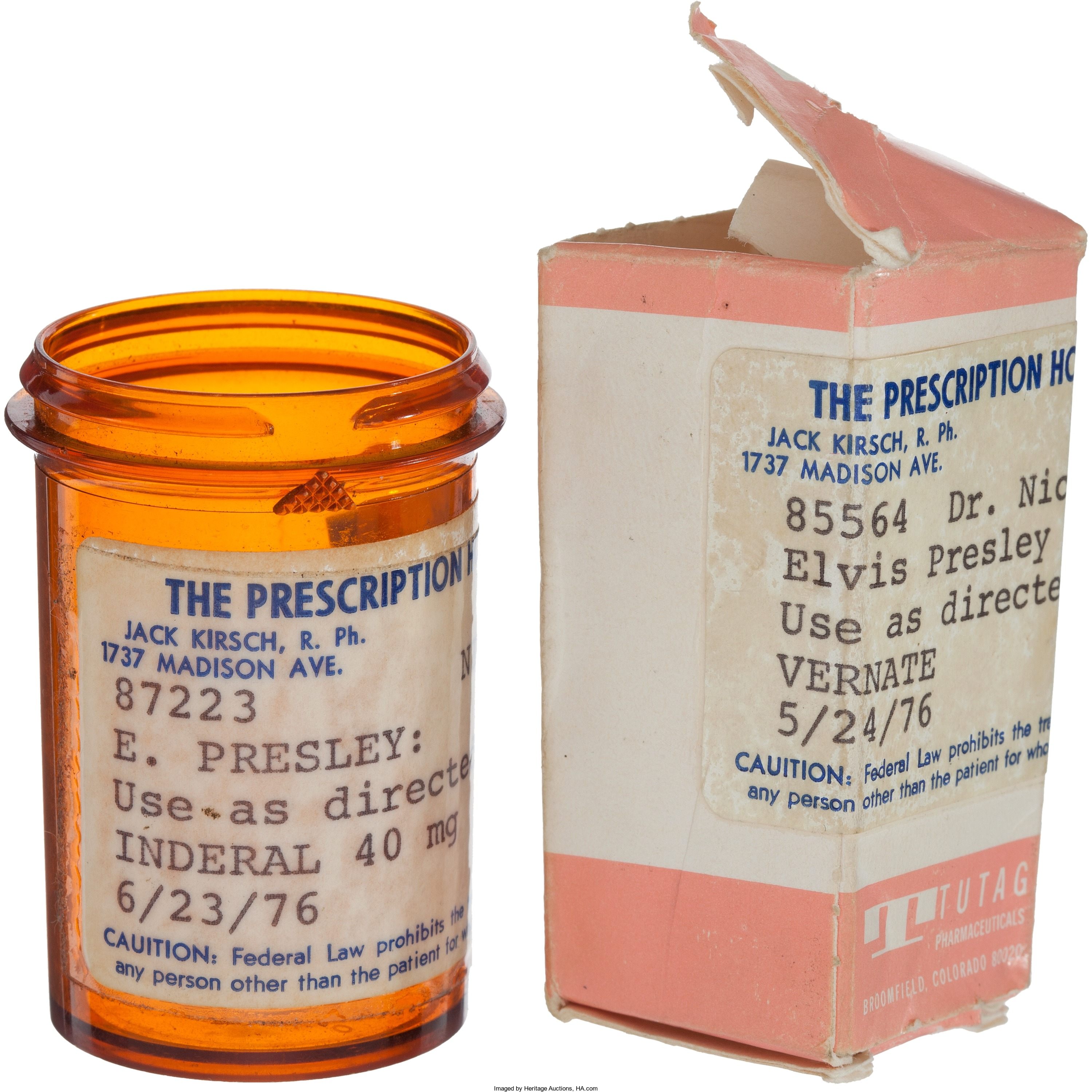

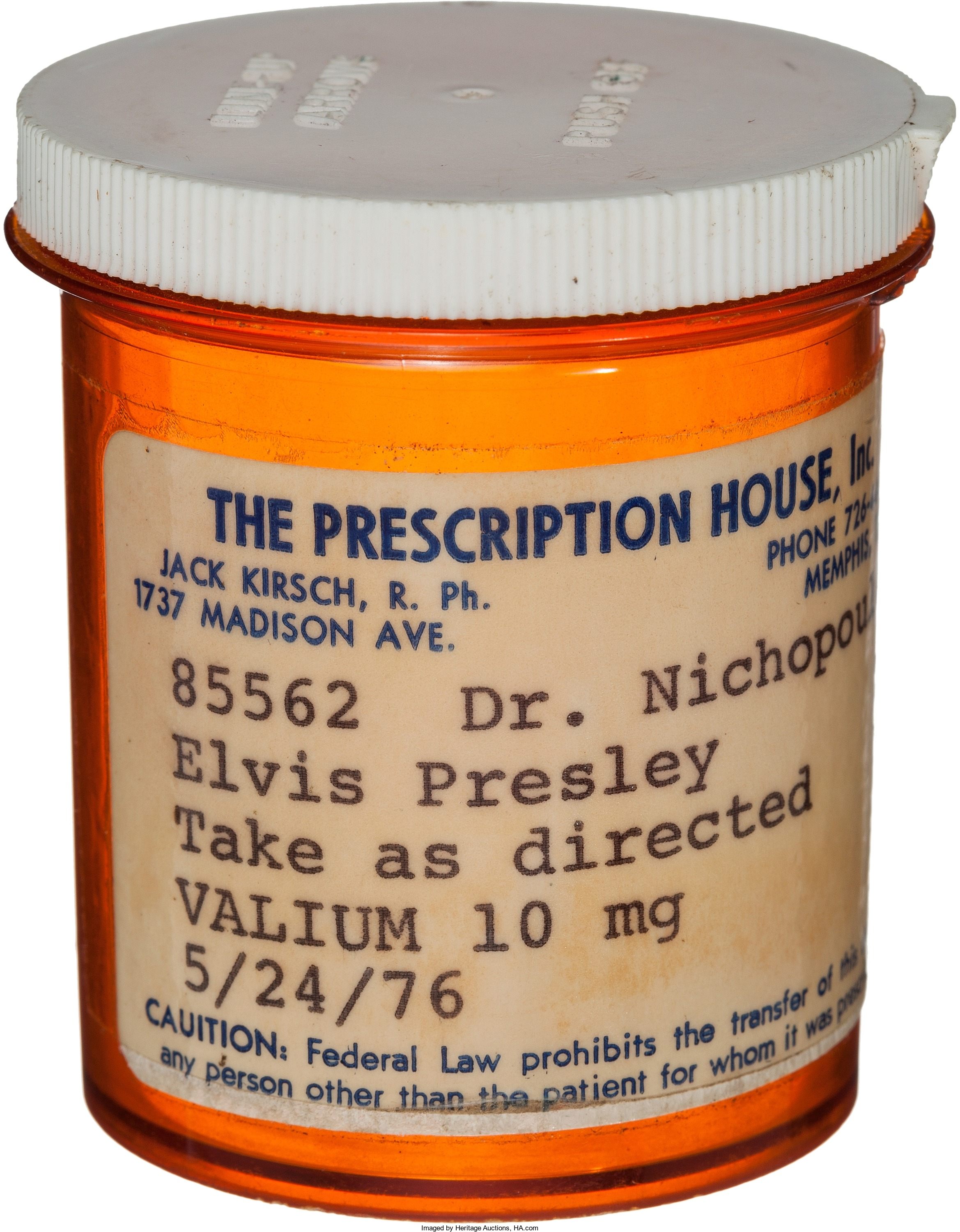

In the last few years, Heritage Auctions in Dallas has offered bottles from the 1970s that originally contained Elvis Presley’s doses of valium, Dexedrine, tetracycline and the beta blocker Inderal. Julien’s Auctions in Los Angeles has offered a smattering of Elvis’s medication bottles from the 1970s, two of which sold for over $6000 each, as well as containers for Michael Jackson’s pain relievers, assortments of Truman Capote’s prescribed drugs and Marilyn Monroe’s barbiturates and anti-allergy pills. Vessels for non-lethal drugs prescribed for Jack Kevorkian have come on the market, too.

Auction lots in this niche field typically sell for a few thousand dollars each. (The three empty Elvis bottles auctioned by Heritage sold for $4,062.50, $3250, and $3,883.75.) They do not contain the actual meds—reselling those would be illegal. Museums, however, are allowed to keep vintage pills on hand—the Smithsonian, for instance, owns Charles Lindbergh’s stashes of barbiturates and anti-malarial quinine from the 1930s and Apollo astronauts’ sleeping aids.

Still, some of the bottles for sale are not entirely empty. A vial for William Burroughs’ methadone supply, which surfaced in 2013 at PBA Galleries in San Francisco, was adapted by a subsequent owner into a mini-memorial for the author. It is filled with dirt and pebbles picked up at Burroughs’ grave in St. Louis, plus a bullet shell from his gun (presumably not the weapon with which he accidentally killed his second wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951). The whole lot—pebbles, pill bottle, bullet shell, and all—sold at auction for $1,320.

Darren Julien, the owner of Julien’s Auctions, says some of the Elvis prescription containers on the market were originally brought to light by a fan who combed through the performer’s trash. When the clearly labeled bottles go on display at homes, museum galleries or auction sale rooms, he says, “people are mesmerized.”

The market has become so feverish that some living celebrities take precautions to protect themselves from any souvenir hunters scrounging in their garbage bins. When they throw out prescription medicine containers, Julien says, “they take off the labels.”

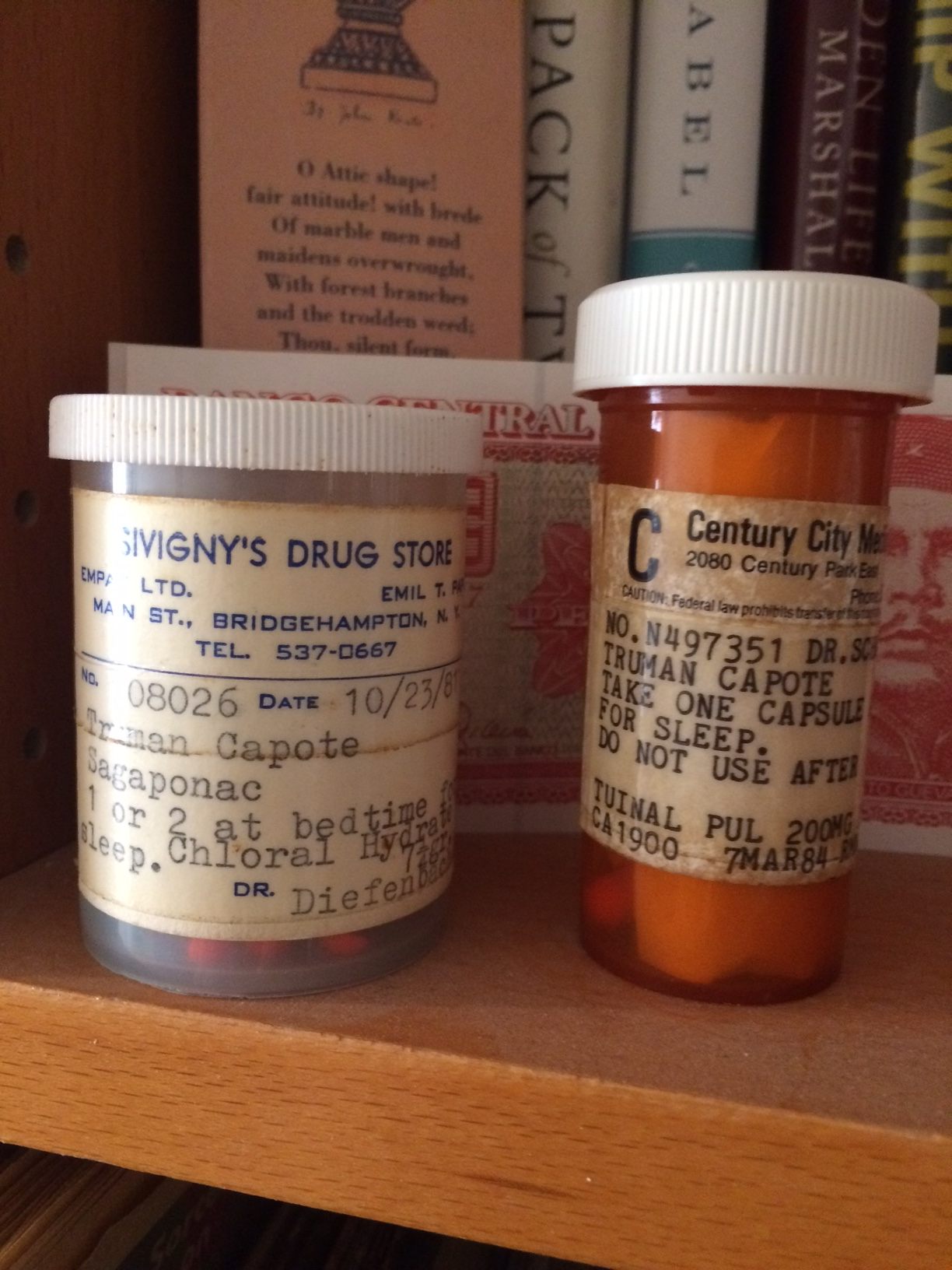

Margaret Barrett, the director of entertainment and music memorabilia at Heritage, owns two of Capote’s bottles, which originally contained the sedatives chloral hydrate and Tuinal. A cocktail of similar prescription meds was found in his bloodstream when he died in 1984, at 59. Ms. Barrett says “he added other drugs to both containers,” and he sometimes tucked handwritten instructions inside noting the quantities of each that he was supposed to take.

She keeps the containers on a bookshelf at her home, casually tucked alongside the books. Visitors at first often assume that the prescriptions were meant for her, and they try to avert their eyes, so they will not appear to be nosy about her health problems.

But she reassures her guests that “you cannot help but look.” She compares people’s curiosity about the Capote artifacts to just about everyone’s covert practice of checking on the contents of their friends’ medicine cabinets.

Other intimate medical artifacts of pop culture idols, including Elvis’ x-rays, have also drawn customers’ attention at auctions.

“It’s a weird world I’m in,” she says.

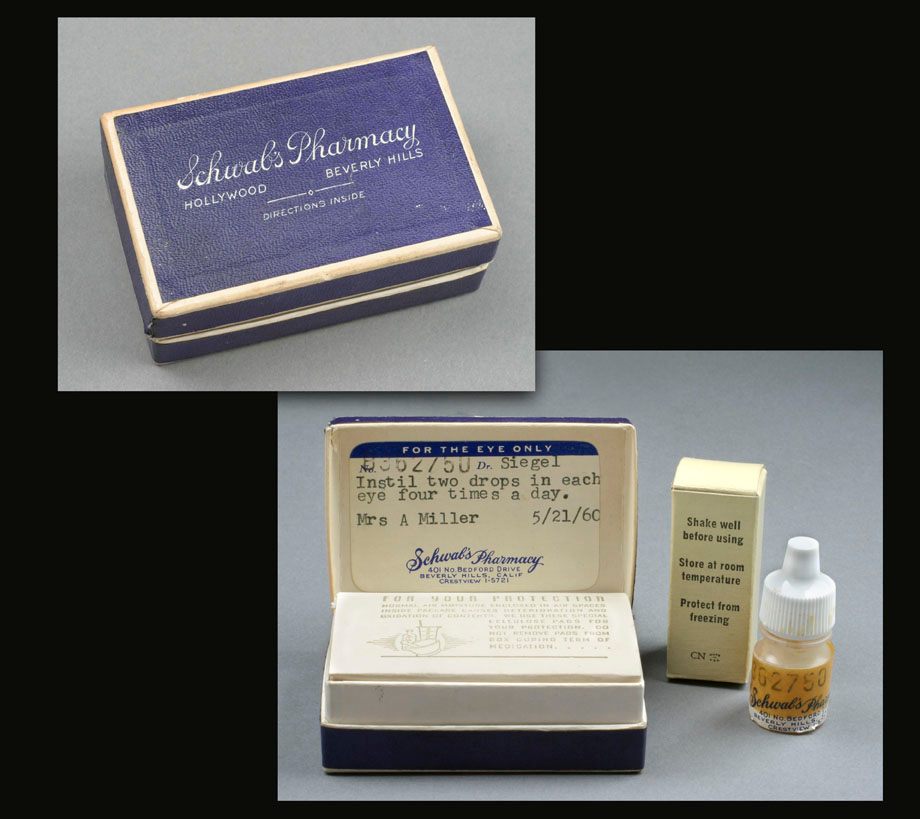

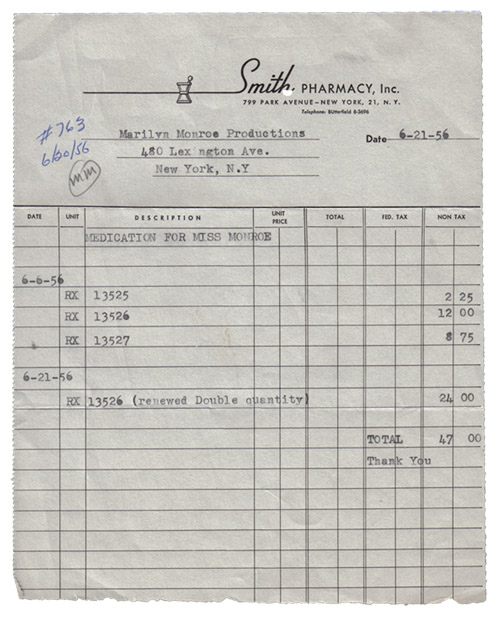

Scott Fortner, a major buyer and scholar of Marilyn Monroe’s former possessions who loans widely to museums, owns bottles for her prescription eye drops and anti-allergy pills. He has bought related paperwork, too, which he stores in a metal file cabinet that Monroe used in her homes. Her telegram to her Beverly Hills psychiatrist (at times she went to therapy sessions every weekday) wishes him and his wife a happy anniversary. An invoice from her Manhattan pharmacy lists one of her drugs as “renewed Double quantity.” Fortner has also acquired jars of her face creams, and in recent months he carefully salvaged strands of her hair that he found strewn on one of her favorite jackets in his collection.

Because of his focus on objects that she owned, he says, he is not much interested in medical records such as her chest x-rays that hospital staff may have taken home. And he would firmly draw the line against acquiring anything as invasive, prurient and morbid as the pair of breast enhancers that were retrieved from the trash at the mortuary where Monroe’s funeral was organized. They are said to have been destined for use on her embalmed corpse.

Fortner points out that there is plenty of other illuminating and emotionally powerful material to collect instead, which she would have wanted her fans to know about. Throughout her tumultuous career, while shedding husbands and movie personas again and again, she somehow remembered to preserve her own memorabilia down to the drugstore receipts and eyedroppers.

“She saved everything,” Fortner says. “She didn’t throw anything away.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook