The Surprising Importance of Skunks in the History of Chicago

An Anishinaabe word for skunk likely inspired the city’s name.

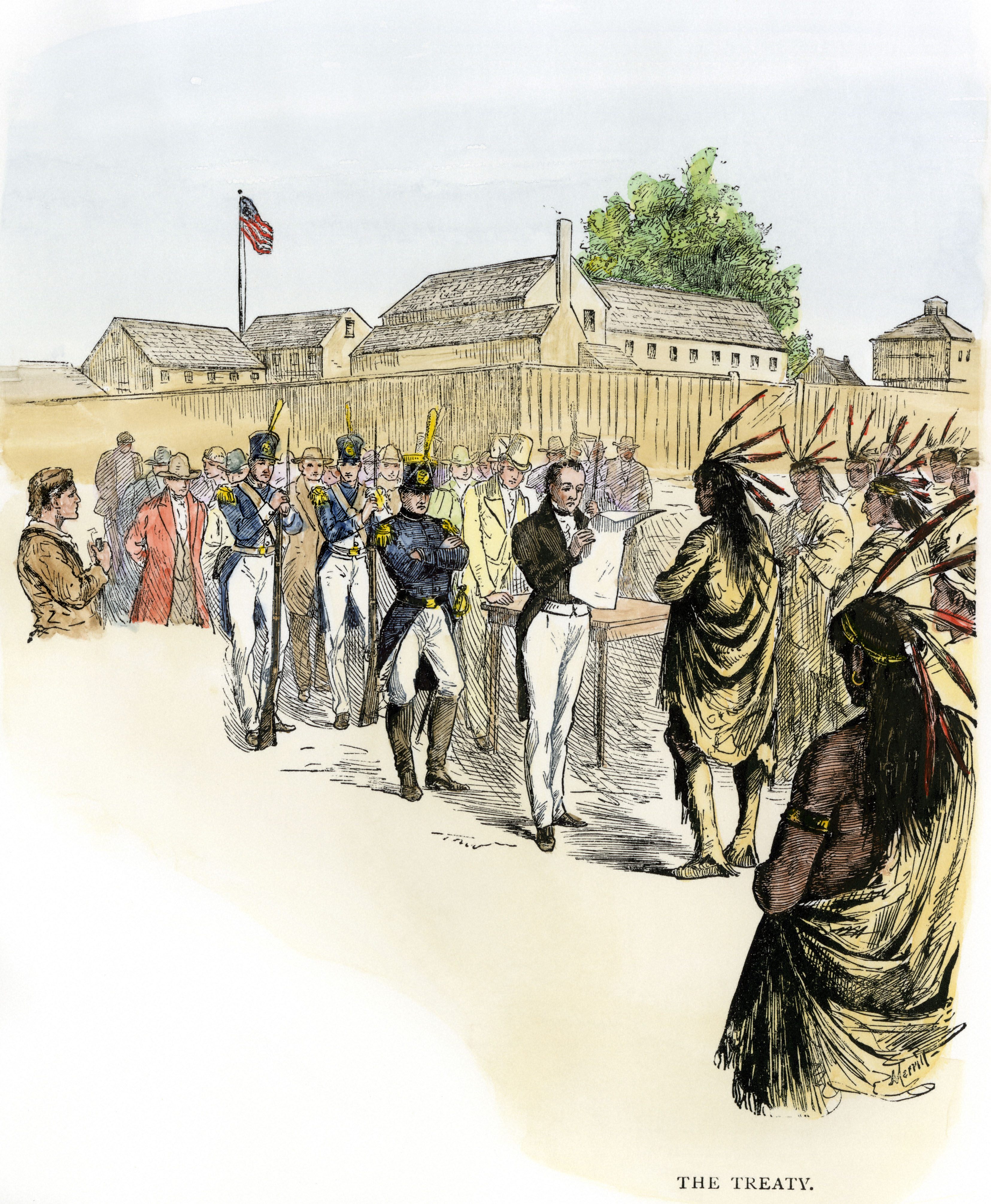

In September of 1833, bands of Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Odawa, and other Anishinaabe and Algonquin peoples gathered in a small fur-trapping town called Chicago, where a shimmering prairie met a vast inland sea. After weeks of coercion, they signed the Treaty of Chicago, transferring to the U.S. government 15 million acres of territory they had inhabited since time immemorial. Though the treaty forced them west, their names for that river—and the town it ran through—stuck.

According to some histories of Chicago, early French explorers derived “Chicago” from a sloppy transliteration of “shikaakwa,” the Miami-Illinois word for smelly wild onions, or “Zhigaagong,” an Ojibwe word meaning “on the skunk.” (Chemically, skunk spray and onions contain oily, sulfurous compounds called thiols, which make them both extremely pungent and difficult to wash away.) Telling the story of the 1833 treaty, Nelson Sheppo, an elder of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi, calls the place his ancestors gathered “skunk town.”

“The whole area of Chicago is named after that animal,” says Edith Leoso, tribal historic preservation officer for the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, whose reservation is in northern Wisconsin. She recalls stories of her Anishinaabe ancestors traveling from their homes on southwestern Lake Superior to the mouth of that smelly river each fall, right as young skunks were setting out in search of new territory. Leoso says that her people often trapped the furry omnivores for their sacs of highly concentrated musk, which Ojibwe medicine people use as a treatment for pneumonia.

The words for skunk and the area’s similarly smelling wild allium plant are inextricably linked in Algonquian languages; Margaret Noodin, an Anishinaabe language teacher, says some Ojibwe people call the plant “skunk cabbage” because of its stench. According to Kyle Malott, a language specialist with the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, the morpheme “zhegak” refers to the way a skunk’s tail stands straight up when threatened, just as the onion grows straight out of the ground. Given these linguistic connections, the plant- and animal-based theories behind the name “Chicago” may both be true.

One thing is certain: Skunks have been part of Chicago’s history since before it was “Chicago,” and 200 years later, they continue to thrive in its urban landscape. Rebecca Fyffe, the director of research for ABC Human Wildlife Control and Prevention, has been sprayed 31 times—six of which were direct hits to the face. Her company removed 832 skunks in 2015 and nearly three times that—2,491—in 2019.

“Skunks are somewhat of a plague of affluence,” Fyffe says. Most of her removal calls come from well-to-do residents with large, lush lawns. In spring and summer, the black and white critters emerge from their cold weather dens and hunt for grubs, digging cone-shaped holes in grassy areas from Northbrook to South Shore. Normally, diseases such as rabies and canine distemper keep skunk populations in check—in the ’70s, skunks were the state’s top carriers of rabies—but falling rates of infection seem to have caused a population explosion.

The boom is part of a natural cycle, says Stan McTaggert, who manages the Wildlife Diversity Program at the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. His agency says that, in 2010, private companies with wildlife-removal permits removed around 6,700 skunks from the Chicago area. In 2017, they removed more than 14,000. (Eventually, skunk diseases will probably pick up again, and those numbers will fall.)

Pestilence isn’t the only skunk-limiting factor—Chicago’s notorious winters also claim their fair share of skunks each year. The urban heat-island effect has drawn skunks deeper into the city in search of warmth: They’ve been seen crossing streets in Lincoln Park, foraging next to Metra tracks in Ravenswood, and burrowing in Graceland Cemetery. Liza Lehrer, assistant director of the Urban Wildlife Institute at the Lincoln Park Zoo, says that the region has historically been a haven for mammals drawn to its mix of prairie and woodland ecosystems.

Today, the Chicago River acts like a wildlife expressway, allowing skunks to travel from the suburbs closer to downtown. Climate change has also softened winters, which spares more skunk parents and results in more litters of up to a dozen baby skunks. “It doesn’t take very long for just a few more skunks in the spring to result in many more skunks occurring in the subsequent fall,” says Stan Gehrt, professor of wildlife ecology at Ohio State University.

Skunks are “bona fide New World animals,” writes Alyce L. Miller in her book Skunk. They were likely some of the first mammals that early European trappers encountered when they reached the Chicago River in the 17th century. They helped the city ride the fur trade to prosperity. By 1920, warm and durable skunk pelts had become the second most valuable fur export in the Americas after muskrat. Skunks still had a stinky connotation, so sellers marketed their pelts with refined names such as “Alaskan sable” and “black marten.” But following World War II, the U.S. Congress passed the Fur Products Labeling Act, requiring sellers to accurately label fur products, and skunks soon fell out of fashion.

Adam Ferguson, manager of the Negaunee Collection of Mammals at the Field Museum, cares for drawers full of taxidermy skunks. Their skins have been stuffed to give their pelts some semblance of a body shape, and their claws, still intact, are ghostly to touch. But their fur is as soft and luxurious as if they were still living.

On a chilly morning in January, while the city’s skunks rest in their winter dens, Ferguson lifts a Mephitis mephitis, or striped skunk, specimen from one of the drawers, its fluffy tail dangling in the absence of any supporting vertebrae. (Taxonomically, the species is aptly named after Mephitis, the Roman minor goddess of poisonous gases and bad smells.) His guess is that the mammals must have been pushed out to the fringes of Chicago as the city grew, but because they’re so adaptable to urban landscapes, they’ve managed to return.

For Leoso, the Ojibwe tribal historic preservation officer, the rich local history of skunks should be celebrated. Perhaps their historical importance, and their modern-day omnipresence, should lead us to treat them as neighbors, not nuisances. “They’re just coming back,” Leoso says. “Just let them go on their merry way.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook