China’s Reincarnation Database Has Verified The Existence of 870 Living Buddhas. But How?

Two monks chatting (probably about this new government list) inside a Tibetan Buddhist monastery. (Photo: Luca Galuzzi/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.5)

While government regulation of reincarnation might sound tricky, China’s Communist Party has gone ahead and given it a go. On January 18, they published an official list of 870 “living Buddhas” who, in Tibetan Buddhism, are believed to be the reincarnations of prominent lamas or religious leaders. The list is available to anyone online, and includes each lama’s name, photo, monastic title, date of birth, certification, and resident monastery.

The number of “living Buddhas” has been increasing at a rapid clip since autumn. In September 2015, China’s State Council released a white paper enumerating 358 “living Buddhas.” By December, there were 360. Now, the final count in the database is 870, which makes one wonder how so many were added so quickly. But then there’s the most salient question: how can reincarnation— a purely religious concept with no scientific criterion—be “verified” in the first place?

Lucy Hornby, China correspondent for the Financial Times, believes the Chinese government likely just chose ”living Buddhas” dwelling in the country’s most important monasteries for its list. “No doubt there is some politics around who got left out, but many expect this to just be a preliminary list that could ultimately be expanded,” Hornby says.

The living Buddha official government database asks you first to enter phone number, verification code, and password before granted entry. (Photo: Screen shot)

And, as with most things, money can help one become a “living Buddha” in China, where local politics are still heavily reliant on bribery. Robert Barnett, a Tibet scholar at Columbia University, has been told that each local official has a quota of “living Buddha” permits that he can divvy up in his region. Tibetans have posted photos to WeChat, a social media platform, showing fake lamas openly giving gifts to top party officials.

“Before, if you had a piece of paper that had been bought from a monastery or faked, it wouldn’t be that credible, except maybe in China rather than in Tibet,” explains Barnett. “Now, there is an official government-issued piece of paper worth a lot of money, that you can go online and check, representing real financial value.”

As for the previously unregulated religious economy of fake Buddhas, Barnett says these posers may number in the thousands. He mentions a Chinese citizen on the mainland who had set up a private phone line for people to call if they had questions about the legitimacy of a certain “living Buddha.” The existence of this sort of “credit check” system, says Barnett, suggests the problem of fakes must be quite prevalent in China.

Indeed, fake “living Buddhas” have swindled money from practitioners and lured them into sexual activities, or worse, raised money for separatist groups, according to Zhu Weiqun, a Chinese political advisor.

Dorshi Rinpoche, a certified “living Buddha” from Amdo county, Tibet, told China’s Xinhua News that criminal activity involving impostors still occurs frequently; he says that in some remote monasteries, he’s heard of the honorary title being put up for sale and traded among businessmen. Even some westerners, including action star Steven Seagal, have been named “living Buddhas,” though their verification status is unclear.

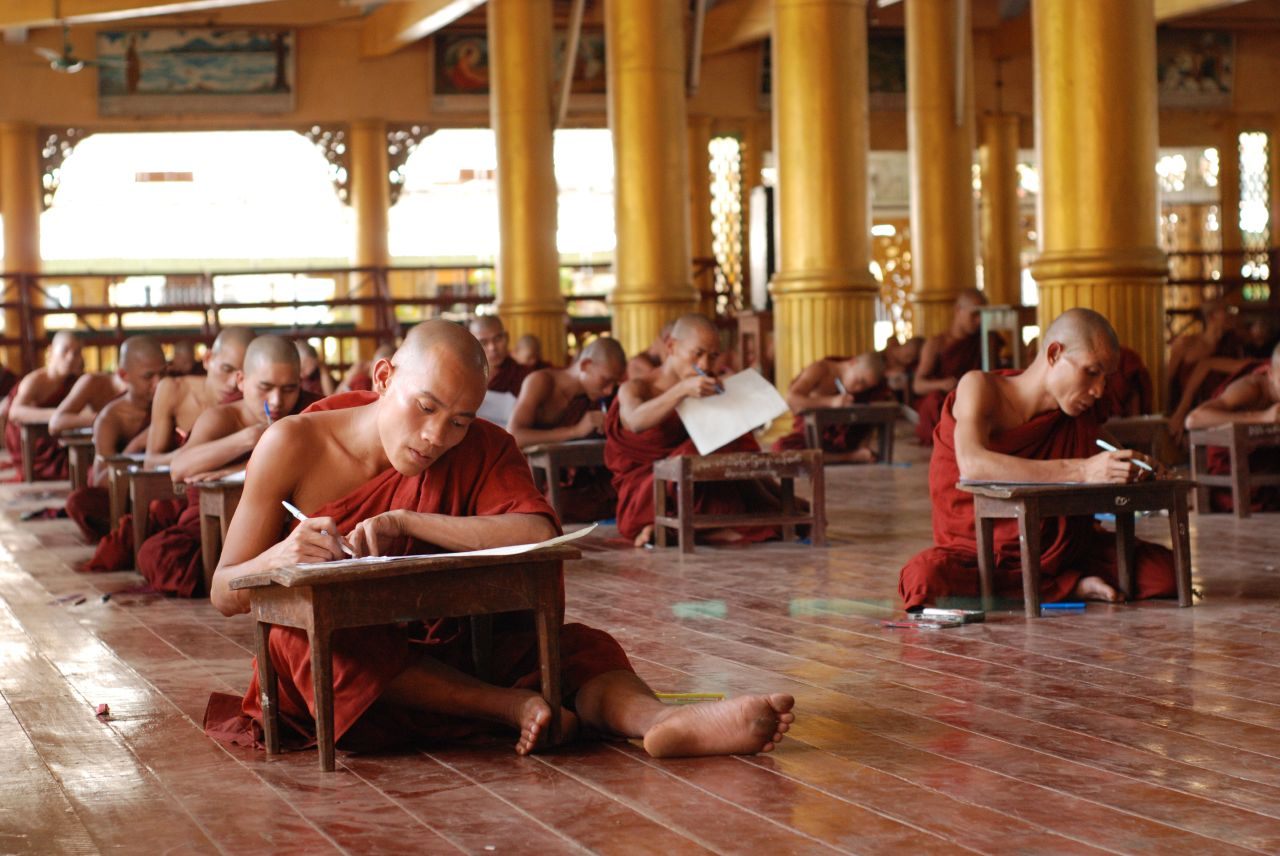

A proper tulku or Rinpoche would have received a proper spiritual education, like these monks in Myanmar. (Photo: magical-world/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

The most high-profile imposter was probably Chinese movie star Zhang Tielin, who in November held a lavish enthronement ceremony in Hong Kong that went viral in a video titled “The ordainment of Zhang Tielin.” Both Zhang and the “living Buddha” who ordained him came under fire; the latter afterward issued an online statement in which he switched to calling himself a yoga practitioner rather than a “living Buddha.”

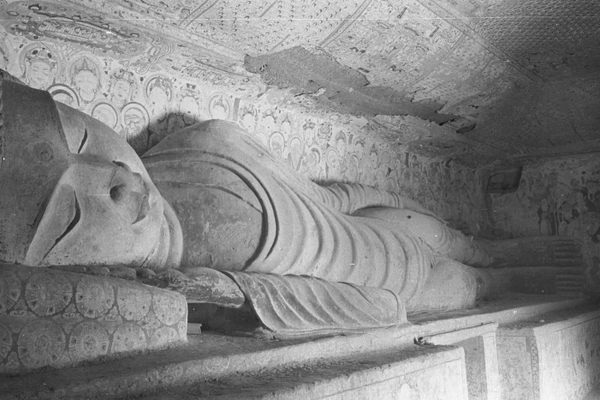

Barnett says that there’s actually no such thing as a “living Buddha” in the Tibetan tradition. He explains that the term was invented by the Chinese, probably centuries ago, to describe something that doesn’t exist in the Tibetan language and and for officials to use it now reflects a distinct lack of knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism. “Reincarnated lama,” he says, is a better translation, but the terms “tulku“ or “Rinpoche“ are even more accurate.

Barnett says that such fraud is largely about social rather than financial exploitation, since being a tulku or Rinpoche means a huge difference in status. “It means that you accomplished a high enough level of meditative achievement in your previous life,” he says, “that upon dying, you didn’t completely lose those qualities and abilities, such as concentration, awareness, compassion, and understanding.”

A reincarnated lama is thus recognized for possessing several lifetimes of wisdom, making him a fast learner and patient teacher. (Inheriting the estate and wealth of the person you are said to be a continuation of is an additional perk.)

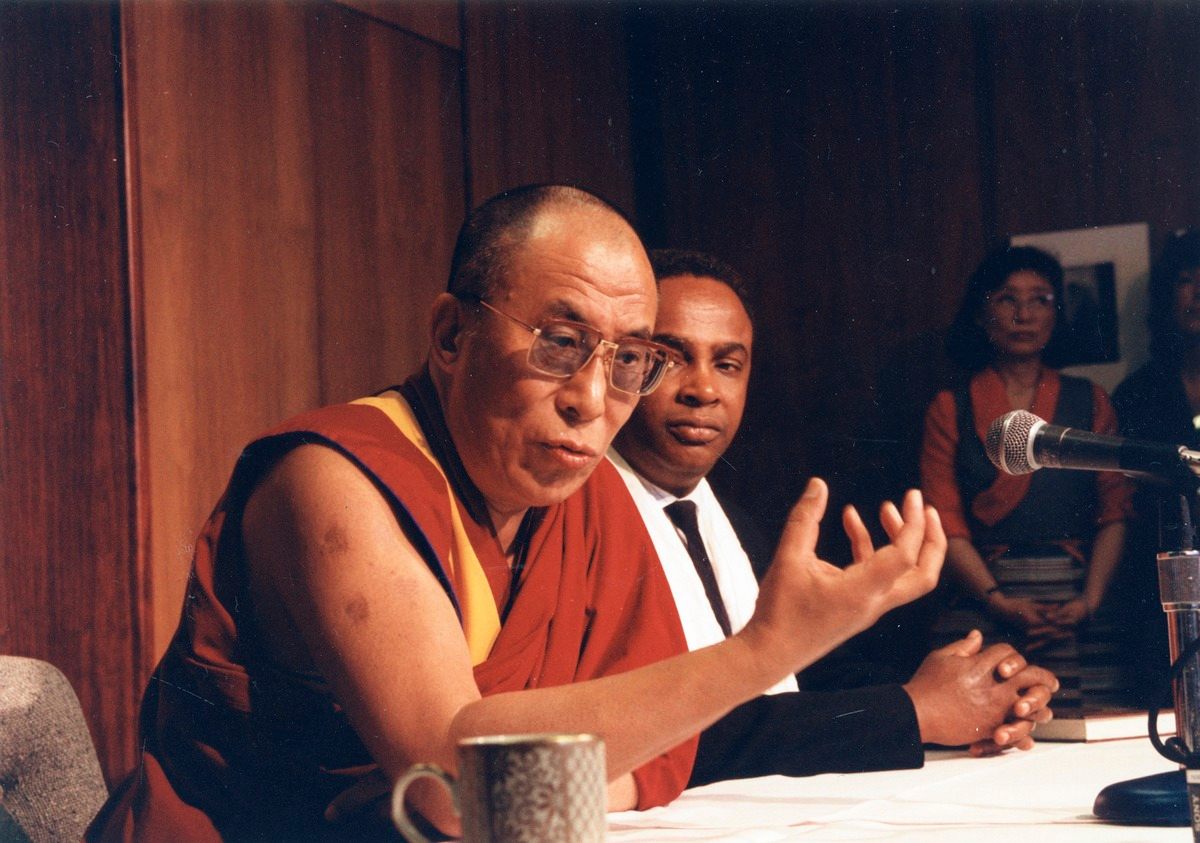

The Chinese government needs to ensure the next Dalai Lama is as excited about China as these kids. (Photo: AlexaHR/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The tradition dates back to the 13th century, though not all Tibetans are followers. In its purest form the selection of a tulku or Rinpoche involves ceremonies, search teams, dreams, visions, confirmations, and finally, enthronements. Proper lamas are guided and mentored from a young age, like the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama’s website states that certain reincarnated lamas have been “recognized through inappropriate and questionable means,” which has damaged the teaching of the Buddha.

The Chinese government—the largest explicitly atheist institution in the world—has steadily increased its religious legislation, whether regarding Christianity or Islam or Buddhism. In previous centuries, Chinese emperors served as spiritual arbiters, confirming important selections regarding reincarnation. Similarly, in 2007, the State Administration for Religious Affairs said all reincarnations of “living Buddhas” must receive government approval, insisting that only the government can decide who reincarnates, whether they reincarnate, and who will be selected.

The Dalai Lama was exiled from Tibet in 1959 after a failed separatist uprising. (Photo: Seattle Municipal Archives/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Dalai Lama might in fact be at the root of what this list is all about. Many observers say that China is trying to exert control rather than solve the problem of fraud with which many Tibetan Buddhists are concerned.

Barnett, who has been banned from China for nine years now, says that the country wants to ensure that they are the ones to choose the next Dalai Lama, not Tibetan leaders or religious figures. However, the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, has said that perhaps there is no longer a need for a Dalai Lama, and that perhaps he won’t reincarnate.

Sorry, Gyatso—looks like the Chinese government might be calling the shots on that.

Correction (2/17): The headline originally referred to 370 Buddhas. It has been changed to 870.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook