When Chinese Americans Were Blamed for 19th-Century Epidemics, They Built Their Own Hospital

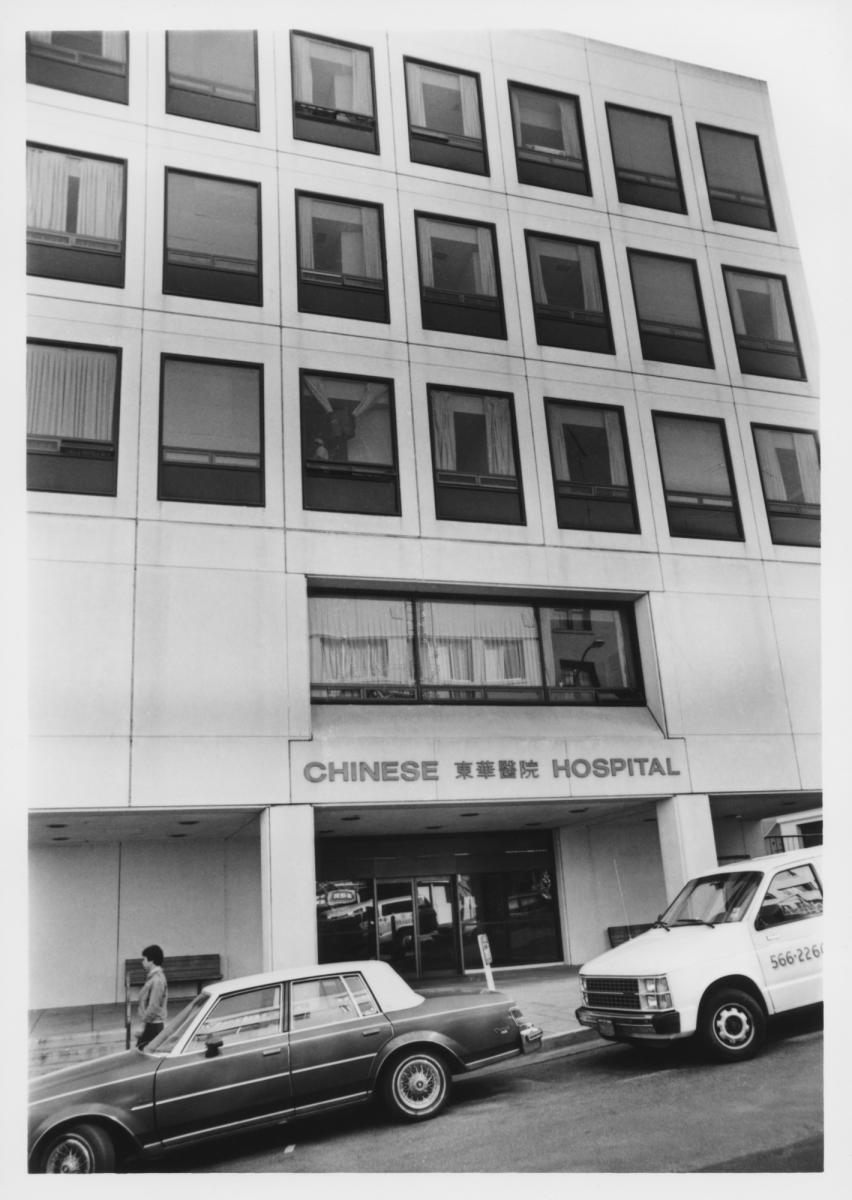

The Chinese Hospital in San Francisco is still one-of-a-kind.

California’s first Chinese immigrants arrived at a tumultuous time. From the 1860s to the early 1900s, a raft of epidemics, from smallpox to cholera, ravaged the San Francisco Bay Area, and especially Chinatown. Lacking scientific research on disease transmission, local health officials often blamed outbreaks on living conditions in Chinatown and the vices of its inhabitants. In 1877, the surgeon Hugh Toland told a congressional committee that Chinese sex workers caused 90 percent of syphilis cases in the city.

This history makes the recent uptick in anti-Asian discrimination, associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, seem searingly familiar. In 1885, San Francisco’s health officer declared Chinatown a “social, moral, and political curse to the community.” The Board of Health proposed draconian measures to quarantine and destroy buildings where infections had spread, demolishing many businesses and homes in the process. Public officials not only portrayed Chinese Americans as breeders of disease, but also denied the group access to health care, refusing to finance critical services in Chinatown and raising the cost of treatment for Chinese patients at municipal hospitals. As a result, the Chinese accounted for less than 0.1 percent of hospital admissions in the late-19th century, according to medical records from city and county institutions.

In response, the Chinese diaspora organized. Well-connected merchants of the Chinese Six Companies—a federation of mutual aid associations—decided to self-fund their own hospital. In 1900, the year the bubonic plague hit San Francisco, Tung Wah Dispensary opened its doors to Chinatown residents, becoming the first Chinese-American medical facility in the continental U.S. A quarter-century later, it became the Chinese Hospital, which now has locations all over the Bay Area.

Laureen Hom, a political science professor at CalPoly Pomona, wrote a case study about the origins of the Dispensary. Atlas Obscura asked her about the long history of discrimination and civic engagement in Chinese enclaves, and how they resonate in the time of the new coronavirus.

With practically no clinics in San Francisco’s Chinatown, how did the Chinese get treated for cholera, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases?

They relied on their own resources. Chinese immigrants from the same family lines or regions in China formed mutual aid associations, and provided the community resources the government denied. They maintained small, makeshift clinics for ailing members. People could also rely on folk healers who provided traditional medicine. These groups became the de-facto community governance in the face of exclusion.

How did the Chinese Six Companies get the funding and manpower to build Tung Wah Dispensary, which was later rebranded the Chinese Hospital?

When we learn about early Chinese history, we focus on working-class laborers. But there were also immigrants from the merchant class—what we would consider the elite. They became leaders of these associations and interacted with public officials to bring services to Chinatown. They were the middlemen. They also had transnational links with associations back in China, which was another way to pull in resources.

What kind of services did the Dispensary provide, and how did life change after Chinatown finally had a hospital of its own?

The introduction of new medical technology was a source of tension in treating Chinese patients, so Tung Wah Dispensary tried to provide both traditional and Western medicine, which was unique. There were three white physicians, and interpreters. Other health care facilities didn’t have that sensitivity. But the results were kind of mixed. The Chinese knew of the high mortality rates at other hospitals and were reluctant to go to what they thought of as the “Death House.” Many saw the Dispensary as a last resort for medical care—a place where you go to die.

After the 1906 earthquake that devastated most of Chinatown, the association began the process of rebuilding the community. They wanted to provide better health facilities and more care, to make sure the Chinese Hospital evolved from the Dispensary. When it opened in 1925, the era was still one of exclusion, and building a hospital in Chinatown was a very important symbolic statement. At that time, Chinese immigrants were seen as “birds of passage”—not a permanent presence in the country. Creating any kind of institution is a way of asserting visibility. It also showed that Chinese people considered themselves Americans.

What are “yellow peril” and “medical scapegoating”?

“Yellow peril” describes this global phenomenon that was happening in the mid-19th century, from this rising fear that people of Asian descent were taking over Europe and the U.S. In the U.S context, it concerns new immigrants coming in and taking over jobs—starting with the Chinese in the 1850s to ’60s. (Today, it’s happening more with Latinx immigrants.)

Economic anxieties led to xenophobic policies to halt immigration. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made Chinese immigrants ineligible for citizenship. They weren’t seen as deserving of resources and services. Medical scapegoating came about through this mix of explicit racism and exploitation of their lack of legal status and social standing as non-citizens. It’s because they were racially excluded that they Chinese had to live downtown, near the industrial core, which was already dirty and deprived of basic services. The exclusion and neglect then fed into the belief that the Chinese were barbaric and unsanitary, and likely carriers of diseases.

What do health care services look like in Chinese-American enclaves today?

The Chinese Hospital in San Francisco is still the only independent hospital run by the Chinese community in the U.S. But the two other major Chinatowns now have their own health care facilities: Chinatown Service Center in Los Angeles [and elsewhere in Los Angeles County] and Charles B. Wang Community Health Center in Manhattan. These are federally qualified health centers that serve low-income groups in particular.

There have also been more social services agencies in Chinatowns since Tung Wah Dispensary came around. Los Angeles has the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, New York has Asian Americans For Equality, Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence. They’re nonprofits that have the cultural sensitivity to serve.

Chinatowns have not reported unusually high rates of COVID-19, but restaurants and shops emptied long before people were ordered to stay home. Do you see a connection between historical anti-Chinese sentiment and recent reactions to the coronavirus?

Chinatowns still have a large working-class population. When I see a lack of cases, I also think about the lack of testing and access to health care. Do these high-poverty regions have clinics that provide basic services? I think it’s indicative of a larger, structural problem. Even in newer Chinatowns like Flushing, Queens, or suburban Chinatowns like Irvine, California, business has slowed. It does have a lot to do with the negative association people have with Chinatown. There was a lot of misinformation, and our leadership didn’t do a good enough job clearing that up.

The makeup of the Chinese diaspora has changed dramatically since the 19th century. Many are young and American-born, and more outspoken against injustices. But many don’t live in or feel very connected to Chinatown. Could they learn from the lessons of the Six Companies and Chinese enclaves of the past?

These associations reflect an older immigrant history. Chinatowns are old, Cantonese areas. Since 1965 [with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act], Chinese immigrants have become more diverse and educated. These groups have lost their original role and became more symbolic cultural institutions. They represent a heritage. The concern in Chinatown now is about the generational shift, and having a new era of leadership. With young people, knowing Asian-American history, and the history of organizing by the associations, is important. That knowledge shapes how you want to be politically engaged. It shows you’re connected to a collective, social history, even if it’s not your own.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook