How Childhoods Spent in Chinese Laundries Tell the Story of America

The laundry: a place to play, grow up, and live out memories both bitter and sweet.

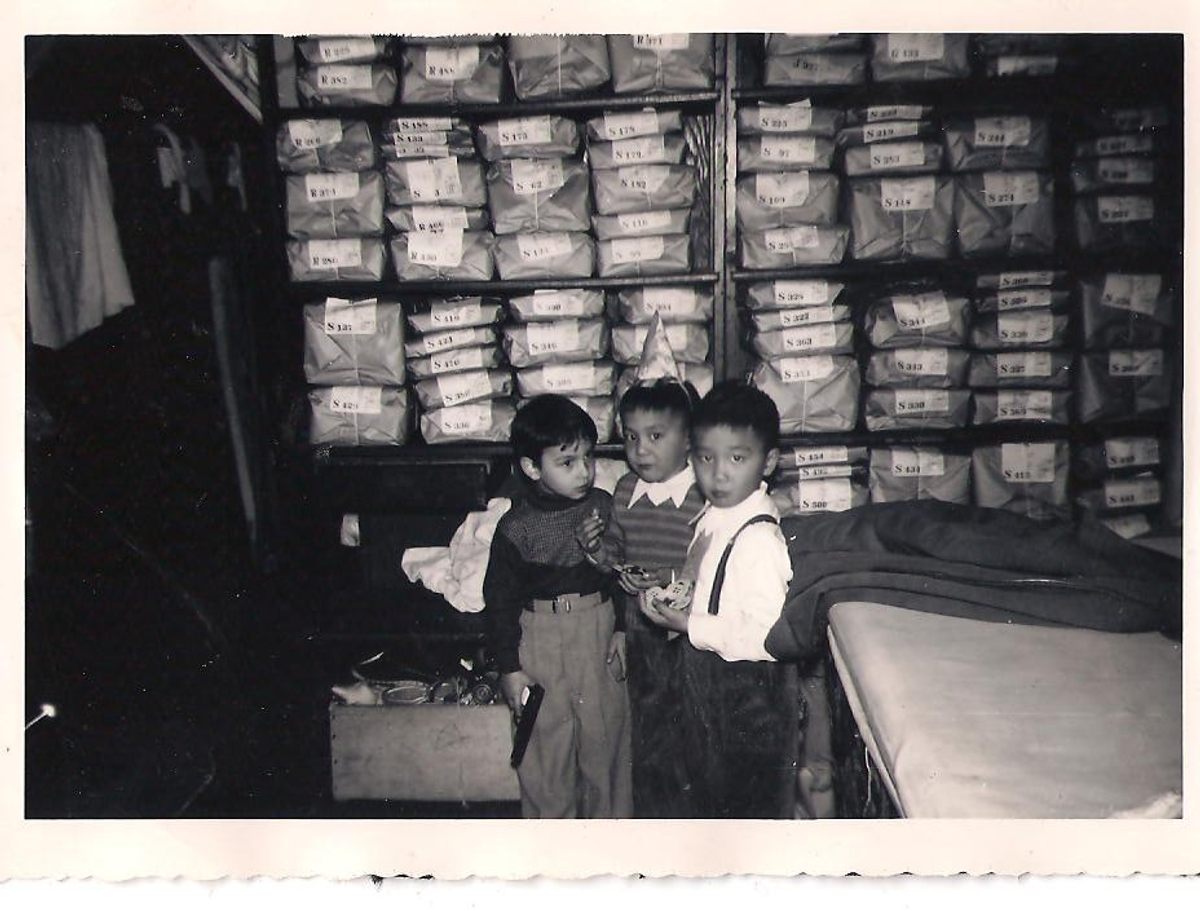

When 81-year-old Debbie Gong Chiu was a child during the 1930s and ‘40s, her father used to tell her to sit in front of their family laundry and wait for the midwife, who would “bring the baby in the black bag.”

“Most of us were born at night,” says Chiu, who is an older sister to five brothers. “[My mother] would work a full day, even though she had pains and everything, then finally they called the midwife. Then the next day she’d be working again, and she’d tell me to watch the baby.”

The family lived in the back of their laundry in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, on Driggs Avenue near the Williamsburgh Savings Bank. It was a Hasidic Jewish area, and on Saturdays, neighbors would come get Debbie’s brother Richie Gong—one of those babies from the black bag—to do tasks prohibited on the Sabbath. “That was how I made money,” says Gong, now 76. “They’d give me a quarter or nickel to turn their lights on or off, or turn on the gas.” For some reason, there was also a rabbi who used to come in, get handed a bowl of white rice by their father, and eat it sitting behind the counter, where he couldn’t be seen from the street. Chiu has no idea how the relationship developed, given that her father didn’t speak English. All he spoke were the few words he needed to interact with customers: “Dollar two cents.” “Okay okay okay.” And of course: “Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday – Sa-ta-nee!” Saturday sounded to her father like Toisanese for “slaughter you,” Chiu explains, so “every time he said it he would laugh.” (Like most Chinese in America back then, Chiu’s parents were from an area of China that spoke Toisanese.)

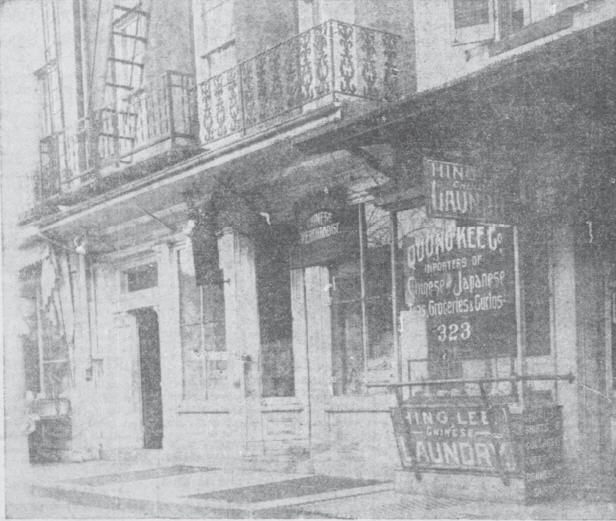

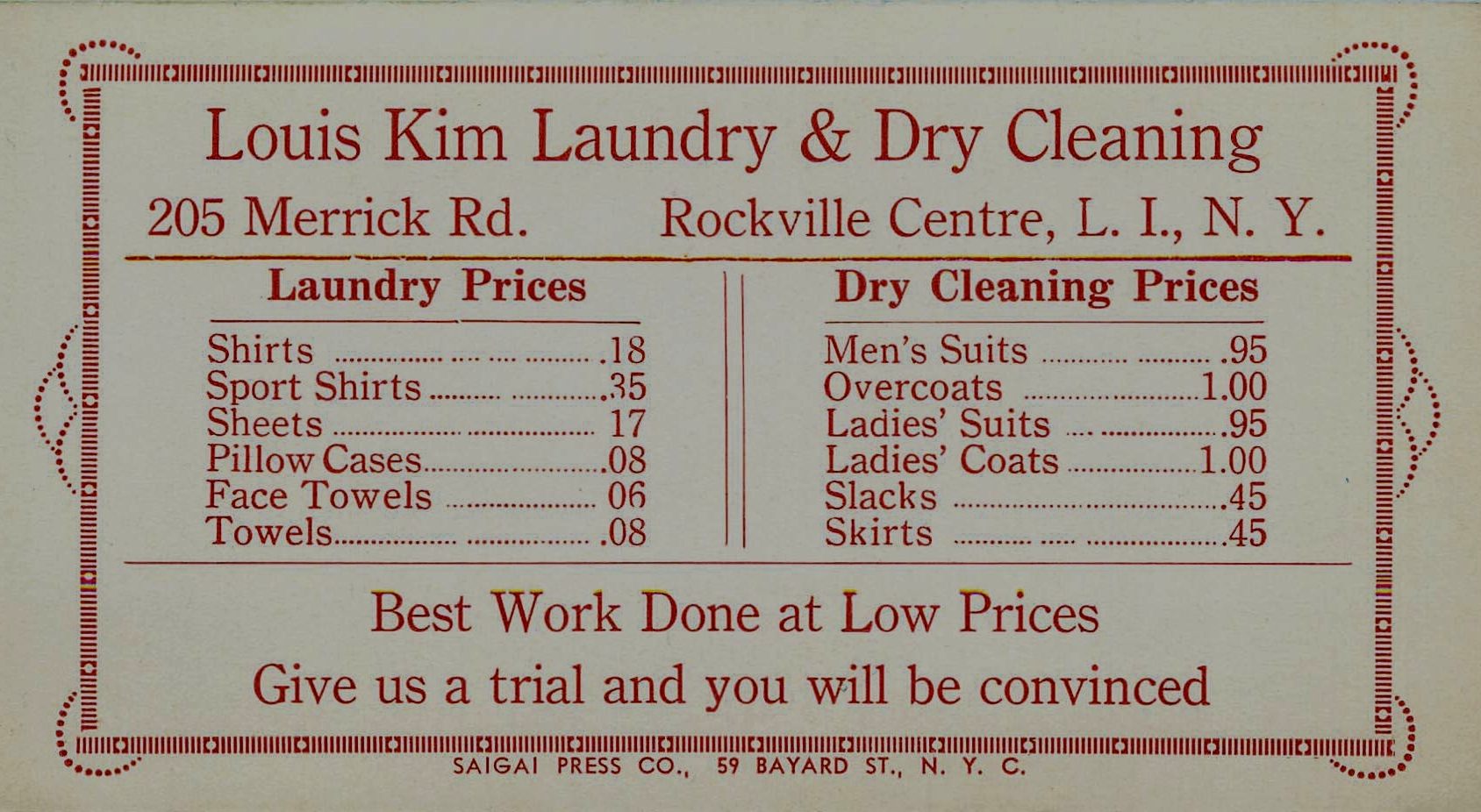

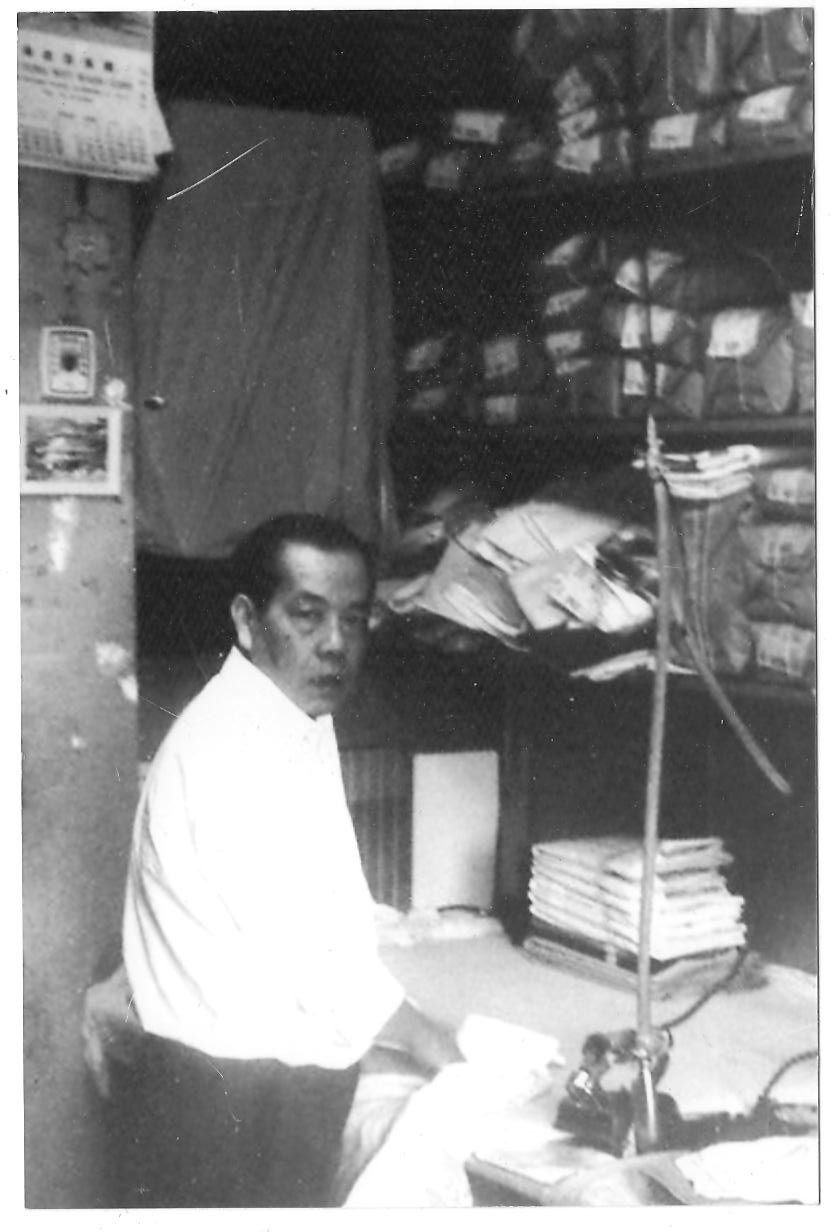

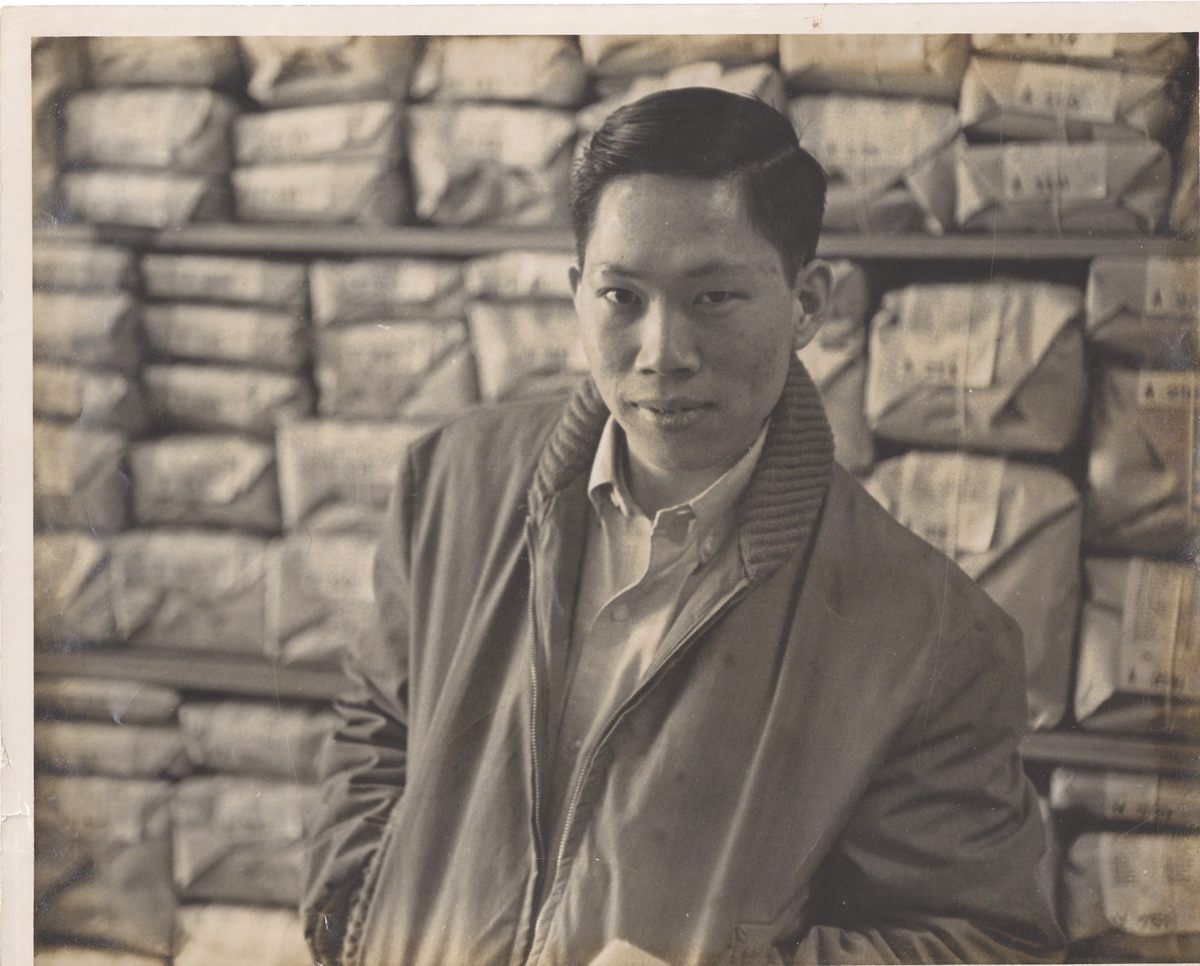

Theirs was one of thousands of laundries across the city owned and operated by Chinese immigrants. Such businesses were so prevalent—at the beginning of the Great Depression, there were an estimated 3,550 in New York City—that they constituted an industry unto themselves, referred to and advertised as “Chinese hand laundries.” For the adults who toiled in them, it was tough, smelly work: it hurt your back, ruined your hands, required touching dirty underwear and used handkerchiefs, and was considered demeaning enough that many hid the true nature of the work from relatives in China. (In letters home, they referred to the laundries as “clothing stores.”)

But for the children who grew up in them, these laundries were home: places where they played, grew up, and lived out memories both bitter and sweet. Their recollections of the days before home washing machines tell not only the history of Chinese in America, but that of New York City—and the country—at large.

Just ask 75-year-old Ray Lee,* who grew up with four siblings in a laundry in Harlem. On Saturdays, he and his neighborhood friends used to sit on Seventh Avenue waiting to see the boxer Sugar Ray Robinson’s famous pink Cadillac, passing on its way to the Hotel Theresa. The hotel hosted big band parties on Saturday nights, and was a center of African-American social life throughout the 1940s and ‘50s. “Sometimes if he got caught at a light we’d yell out to him, and he’d honk his horn at us,” Lee recalls. “And he would double-park his car and never get a ticket.”

Young men often came into the laundry on Fridays and asked to take out just one white shirt, so they could go out for the weekend. The next week, they’d come for the rest. Some people never came back—they couldn’t afford to—and in those cases, Lee’s father sold the clothing to a rag dealer. Lee’s mother did a lot of something called fan lian in Toisanese, which means “turn collar.” She’d remove a worn collar, flip it over, then stitch it back on so the shirt looked new again. “We were all poor back then,” says Lee. His father often bartered services. “The superintendent of our building installed wooden shelves for us, and my father didn’t know what to pay him, but all he wanted was fried rice. So my mother made him a big pot, and he said, ‘Oh this is delicious!’”

Lee’s father taught college in China, then was a merchant in Cuba, but like many other non-English-speakers, could only find manual labor work in the United States. At one point, Lee says their bathtub was taken away, because his father failed to pay a bribe to a housing official who said they couldn’t live in the laundry. “We had to improvise how to bathe. Then eventually we put back another tub because the guy never came back.” Other times, police officers would come by, make an accusation, “and you gave them five or 10 dollars and they would disappear. It was a corrupt area where they knew they could take advantage of immigrants,” says Lee.

For more than a century, Chinese in America were synonymous with laundries in the American imagination. As recently as the 1970s, a Calgon commercial portrayed a Chinese-American couple who owned a laundry and washed clothes with the help of “ancient Chinese secrets” (a.k.a. Calgon detergent).

The link began during the Gold Rush: there were few women available out West to do laundry, and white men generally considered the work beneath them, so laundry was shipped all the way to Hong Kong for an exorbitant $12 per dozen shirts, and took four months to come back. Later, it was sent to Honolulu for $8 per dozen. (Both options were cheaper than shipping it back East.) Chinese entrepreneurs in San Francisco spotted an opportunity. The first known Chinese laundry was opened by one Wah Lee in 1851, who charged $5 to wash a dozen shirts.

As more Chinese arrived out West, white resentment began to build against them, flaring into violence when the economy worsened during the 1870s. In Los Angeles, a white mob killed 17 Chinese men on one night in 1871. Accounts vary as to the killing methods, but all or almost all were reported to have been lynched. In other towns, Chinese were burned or driven out at gunpoint. Whites who hired Chinese were attacked, too. Over time, Chinese were pushed out of mining and other “men’s” work, and into safely undesirable industries like laundry. In 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred low-skill Chinese immigration and further cemented their ghettoization into an industry that required little training, English, or startup costs. The 1920 Census showed nearly 30 percent of all employed Chinese in the United States working in laundries.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place when Chiu’s and Lee’s parents came to this country. For that reason, many laundry workers arrived as “paper sons” and daughters, i.e. under citizenship papers purchased in other names from other Chinese. The Act was finally repealed (but replaced with a tiny quota of just 105 Chinese immigrants per year) in 1943, due in large part to World War II, when the U.S. needed China as an ally against Japan. The negative perception of Chinese in the country began to shift, and more opportunities opened for increasing numbers of Chinese —including the children of laundry workers.

One such child was 69-year-old John Chang, a pharmacist and retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army. Chang’s parents had laundries in Manhattan, then the Bronx (“I went from Grand Street in Chinatown to Grand Concourse in the Bronx”), then Hastings-on-Hudson, a small town north of the city where they fell in love with the trees and fresh air. It was the 1950s, and the Korean War was ending. “My father being Asian, they assumed he was Korean, and they broke his window. They broke his window several times,” says Chang. His father had been a parachutist in WWII, and posted his military discharge papers in the window. After that, the vandalism stopped.

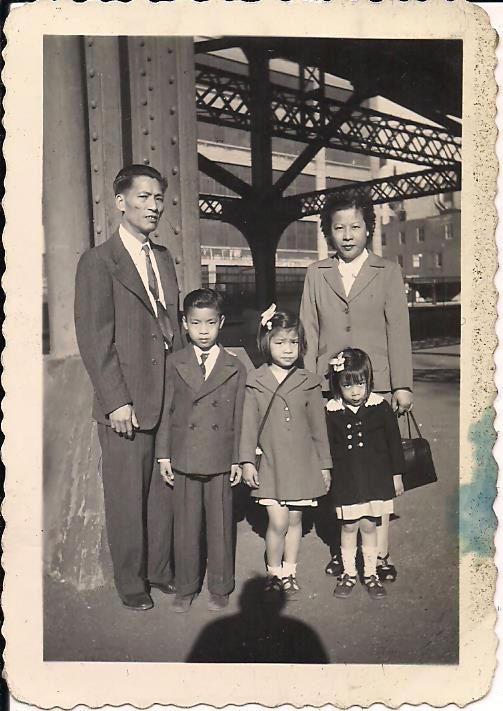

More of Chang’s recollections, along with those of Chiu, Gong, Lee, and many other former laundry children, are collected in New York City Chinatown Chinese, a book self-published earlier this year by Jean Lau Chin, a 73-year-old psychology professor at Adelphi University in New York. Chin grew up above her parents’ laundry on Marcy Avenue in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It was called the Louis Tong Hand Laundry and customers called her father Louis, assuming that was his name. “He always greeted them in return and never corrected them,” says Chin.

On Sundays, the family would visit the Lau clan association in Chinatown, where members of the same village gathered to reminisce. Jean’s was usually the only family in the room; the others were bachelor laundrymen with wives in China. U.S. immigration laws initially kept them apart; after 1949, so would the Chinese Communist revolution. When asked what he did, her father used to say, “What is there to do? I work a laundry!” Jean recalls. The other laundrymen would lament, “The lo faan [whites or foreigners] will not you let do anything else.”

In another book called Learning from My Mother’s Voice, Chin translates several years of oral histories she recorded from her mother Fung Gor Lee, who, after fleeing to Hong Kong during the Japanese invasion of Nanjing, China, arrived in the United States to join her husband in 1939, as a paper daughter, and died in 1995 at age 84: “We all wanted to come to America. The stories we heard sounded like paradise …We expected the streets to be paved with gold. Our stomachs would be full. We would never go wanting. All we had to do was work. Little did we know how hard that was to be, and that we would all be working in a laundry … I never realized how difficult it was until I got here.”

She goes on to recount her life in America: three months detained on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, an early miscarriage, giving birth to three children, strange occurrences in the laundry that convinced her it was haunted, her guilt over the time a rat bit Jean’s thumb in the crib (leaving a scar Jean still has today), the anxiety she felt for the son she’d had to leave behind in China and would not see for 50 years.

With time, her American children grew up, went to college, and got white-collar jobs. They bought big homes in the suburbs, and had children of their own. American immigration laws changed, and the son in China came to the U.S. Meanwhile, household washing machines became ubiquitous, and clothes got cheaper and more casual. By the 1980s, it even became fashionable to wear ripped jeans and wrinkled clothes. Chin recalls a time when her nephew stuffed his freshly washed clothes into a basket to get the perfect set of wrinkles.

“My mother noticed how wrinkled they were; from her days as a laundrywoman, she ‘took pity’ on him and ironed all his shirts smooth. Ever the respectful grandchild, my nephew dared not correct her. When [she] found the clothes she had neatly ironed wrinkled up back in the basket, she was confused,” writes Chin. “She shook her head in disbelief when I explained that this was the fashion.”

*Correction: We originally referred to Ray Lee as “Raymond Lee.” Ray is his full first name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook