Early Chinese Trick Photography Sent Chubby Babies Into Space

Inside a historian’s collection of endearing, goofy early 20th-century portraits.

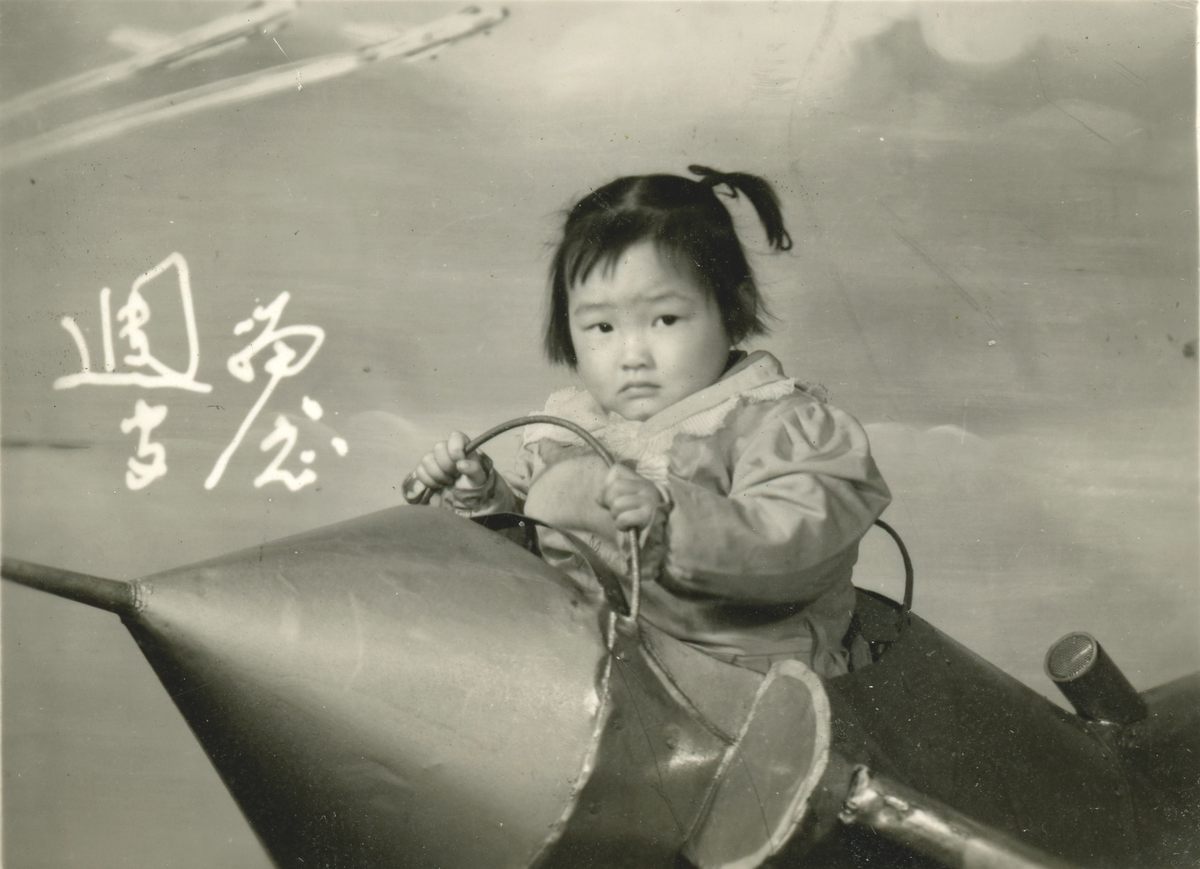

At first glance, the image seems set in space, or at least the set of a low-budget science fiction movie. A stubby Sputnik hovers in the background, next to a flat moon. A sleek metal rocket, labeled YI FENG 02, hangs in the foreground, but instead of an astronaut, it holds a serious-looking baby who gazes off in the distance, unperturbed by the lack of oxygen, zero air pressure, and freezing temperatures of space.

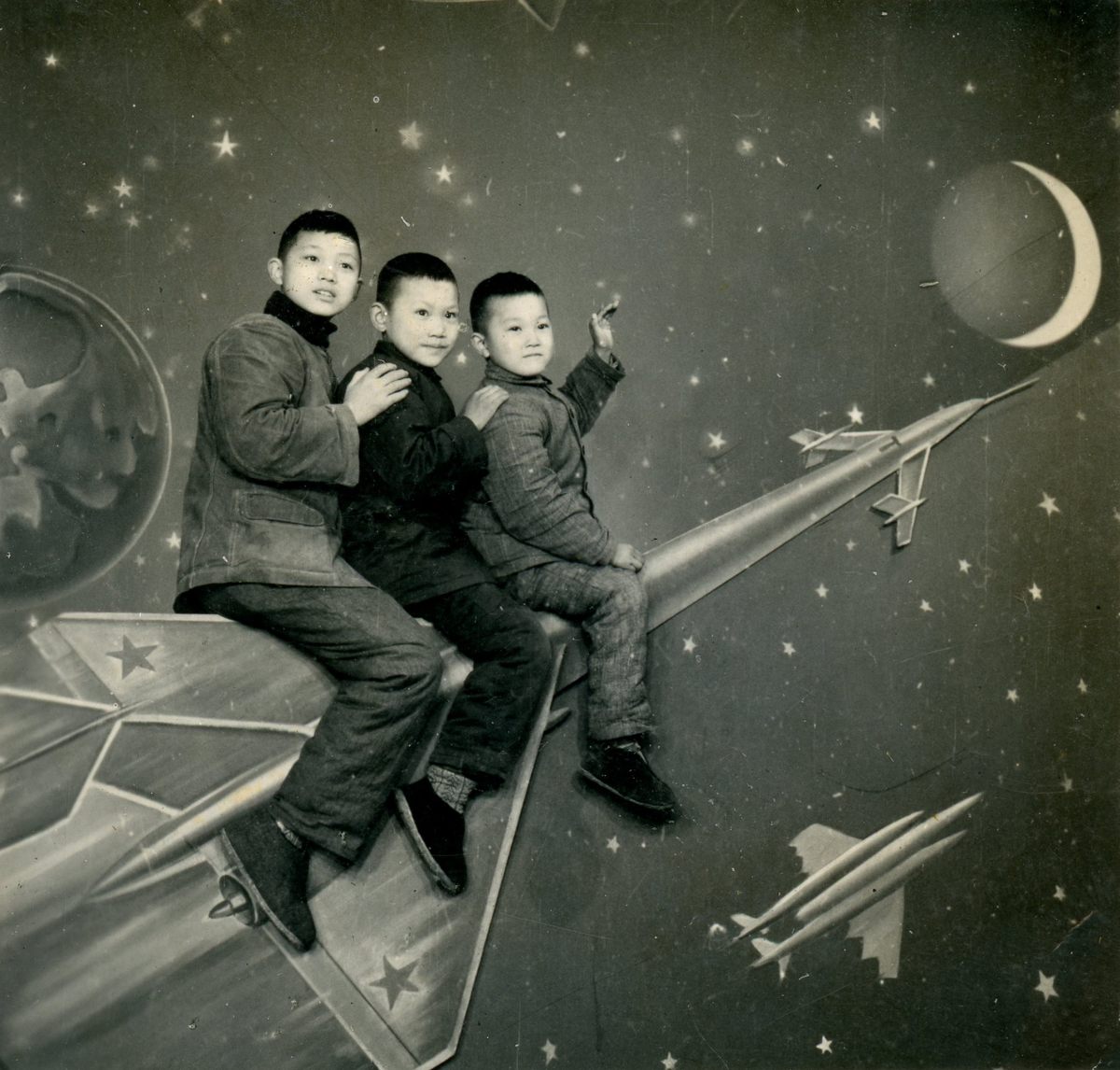

Fortunately for the baby, the image was taken in a professional photo studio. It’s a prime example of early staged and trick studio photography, which gained popularity in China in the mid-20th century. YI FENG 02’s rocket baby is one of more than 8,000 photos in the personal collection of Chris Steiner, an art historian at Connecticut College. Six years ago, Steiner started collecting examples of this kind of studio photography, on eBay and at special photo shows, to show his undergraduate students. But as his collection ballooned in size, he discovered some intriguing recurring themes. “Airplanes, balloons, people posing as fake cowboys, men posing with fake women,” he says.

Trick photography has been around almost as long as photography itself, long before Photoshop, as early as the 1840s, according to an overview from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibit on the practice, Faking It. Early methods of manipulation included painting photographic prints and negatives, making double-exposures, and bleaching parts of the photos. But Steiner felt drawn to a less technical kind of illusion that required no manipulation of the negative—only manipulation of the subjects and studio settings. “The photos you’re dealing with are not using double exposure, but instead props and painted backdrops, with some forced perspective and trompe l’oeil to create the ‘trick’ effect,” Christopher Rea, a cultural historian at the University of British Columbia, writes in an email.

These commercial, quasi-trick photos first emerged in the United States in Europe around the 1890s, Steiner says. The most famous backdrop of these studio photographs is the paper moon (Steiner’s instagram is devoted to the subject). The earliest examples in Steiner’s collection depict people posing in fake boats. “Then in 1907, you start to see people posing in fake airplanes, fake balloons, fake trains,” he says. The theme is so prevalent that it makes up one of the largest subsections in Steiner’s collection, which he has accurately labeled: “People posing in fake modes of transport.”

These photos proliferated in the first half of the 20th century, as the tools of photography became less cumbersome and expensive, and more widely available. Photography suddenly expanded from high-class portraiture to offer opportunities for regular people to play around: pretending to steer a boat, or putting an infant in a rocketship. “None of this is considered to be high art,” Steiner says. “A lot of people who collect high-end photography would never touch this stuff.”

The technology also moved overseas, resulting in an international phenomenon of people simply chuffed to pose in fake modes of transport—often ones they’d never have access to otherwise. Two years ago, Steiner found two eBay sellers based in Beijing who began posting eight or nine photos a week from Chinese studios, regional variations of the age-old theme. He’d stay online until an auction closed—every Saturday at 11 p.m.—to buy the ones he wanted, each around an inch-and-a-half long. (Steiner attributes the tiny size to the relatively high cost of the paper.)

For the most part, the images look like riffs on the American images he’d seen before, featuring men and women posing in fake airplanes or automobiles, but he also noticed dozens of images like nothing he’d seen before. “Babies holding flowers … on rockets?” he says. “I had no clue why.” He tried emailing the sellers to see if they had any information, but they could only offer a range of dates in which the images might have been taken. Some photos contain the label of the studio in which they’d been taken, such 3888 or Great Wall Studio. There were also babies—mostly boys—in planes and helicopters, smiling or frowning.

“Professional photo studios in China have made use of props like these fake [or] cardboard cars, boats, and planes since [the] early 20th century,” Tiffany Lee, an art historian at Swarthmore University who studies early Chinese photography, writes in an email. One 1912 price list from a Shanghai photo studio offered patrons both Western and traditional Chinese costumes, various photo manipulations, and the option to take a photo in a “flying vessel with two seats.” The photos were often taken to mark a special event, such as a birthday, according to Claire Roberts, an art historian at the University of Melbourne. “They are playful photos,” she writes in an email. “In the case of flying, perhaps to suggest the hope of lofty achievement.”

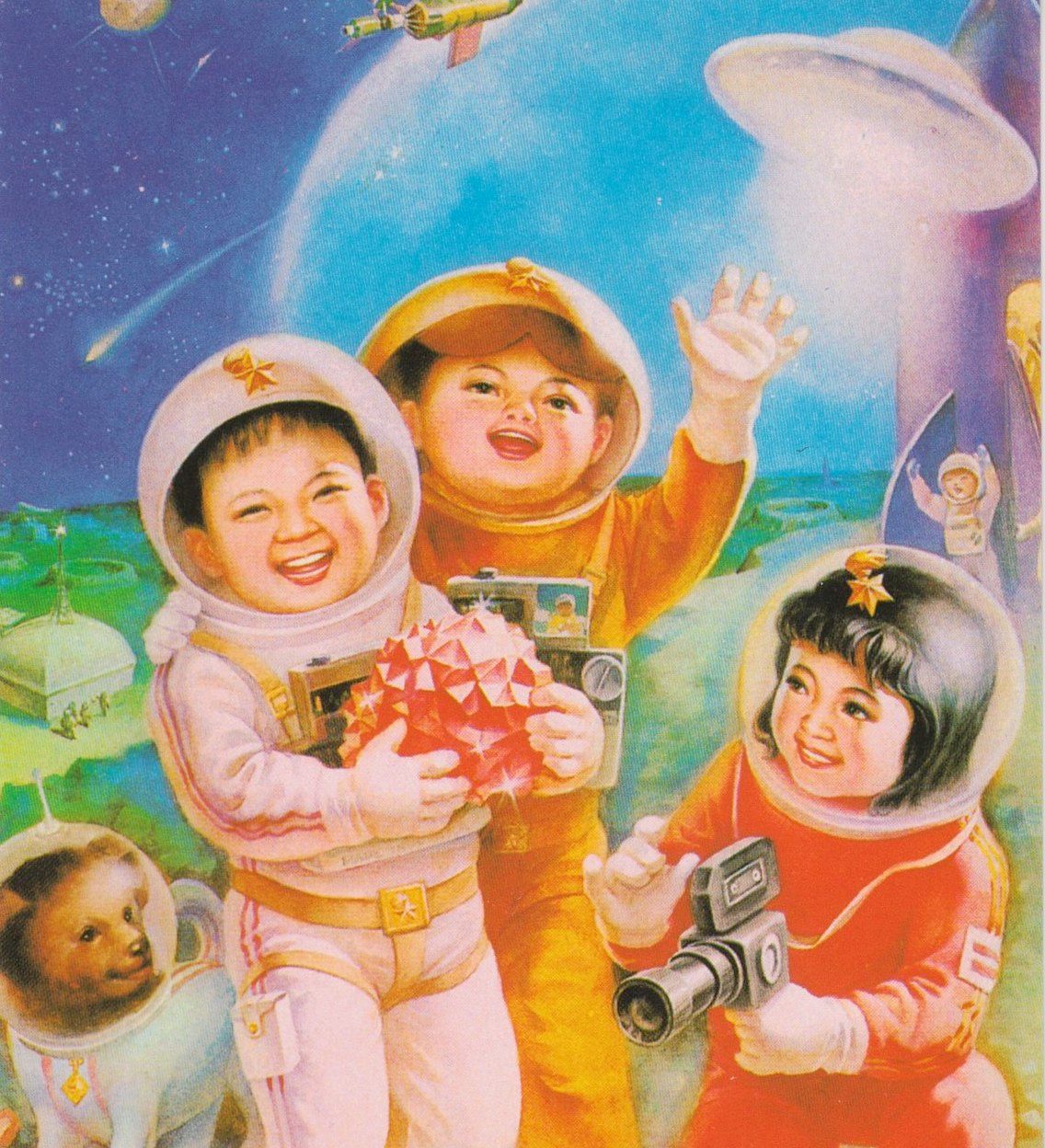

The chubby rocket babies also recall traditional Chinese nianhua, auspicious folk illustrations for the Lunar New Year, according to Rea. “These were works of art, printed in the millions, that families would stick on their walls,” he says. People would display their nianhua on their front gates, doors, and elsewhere throughout the house, meant to bring in prosperity in the New Year. Nianhua were soon appropriated in the 1970s by the Communist Party of China, which produced propaganda posters covered with images of children, often in planes and rockets, Lee says.

These images referred “specifically to (nascent) Chinese space programs in the age of Sputnik,” Rea writes. China was still allied with the Soviet Union at the time and saw the Soviet venture into space as proof of socialism’s technological superiority over capitalism, Nicolai Volland, a cultural historian at Pennsylvania State, writes in an email. It was like the old tradition of nianhua, just in a new medium.

Though trick photography was an international favorite, Steiner says he notices regional tropes such as the rocket babies. Some have clear histories, such as the Chinese qiuji tu, or “self-beseeching photograph.” These photos were double-exposed to show the subject twice—as a peasant and again as a rich person, so they appeared to be begging from themselves, Rea writes in The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China. Another popular set of images, this time from the United States, depicted people picking oranges, often accompanied by some variant of the message, “I’ll eat oranges for you and you throw snowballs for me,” and were sent either from California or Florida. “It was to gloat that you could get oranges in the winter,” Steiner says. “I had to stop collecting them because there are just too many.”

Other local themes leave Steiner guessing. For example, he has amassed a collection of postcards from towns in coastal Croatia in which people pose with their heads in the maws of ghoulish cartoon sharks. Steiner’s best guess? “Apparently great whites were present in the Adriatic, especially during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries,” he writes in an email.

Steiner hopes that the boxes and boxes of photos on his living room bookshelf will help move this chapter of photographic history out of the margins. “That’s one of the things that’s frustrating about all these photographs, [they] come to you with no explanation or no history,” he says. But even if the photos’ origins can’t be recovered, their humor is timeless. Meaning, it’s never not funny to see a chubby kid sitting on a rocketship, looking like he’d rather be anywhere else.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook