Inside the ‘Chitlin Circuit,’ a Jim Crow-Era Safe Space for Black Performers

It’s where legends like Tina Turner and Ray Charles launched their careers.

“Sometimes you play for the chitlins, that’s what you would get,” said Bobby Rush, a blues musician and self-proclaimed “King of the Chitlin Circuit,” in a 2021 interview for the Nashville Tennessean. “We played so well in Argo, Illinois, not Chicago, a suburb of Chicago, the guy [gave] us two plates of chitlins and four hamburgers.”

Rush was describing his experience on the informal network of Black-centered entertainment venues brilliantly nicknamed “The Chitlin Circuit.” Chitlins, short for “chitterlings,” are fried or stewed animal intestines, usually from hogs. An iconic dish in African American food traditions, they have a working-class vibe, even though the dish has shown up at high-class affairs. It’s a fantastic and meaty metaphor for the ad-hoc collection of churches, jook joints, nightclubs, restaurants, and theaters that inspired dreams of fame and fortune for many noteworthy Black entertainers such as Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Jimi Hendrix, and Tina Turner. It’s hard to name a Black entertainer in the 20th century who didn’t perform on the circuit, which inspired many myths and misconceptions. To this day, the Chitlin Circuit remains a potent symbol of resilience in African American creative culture.

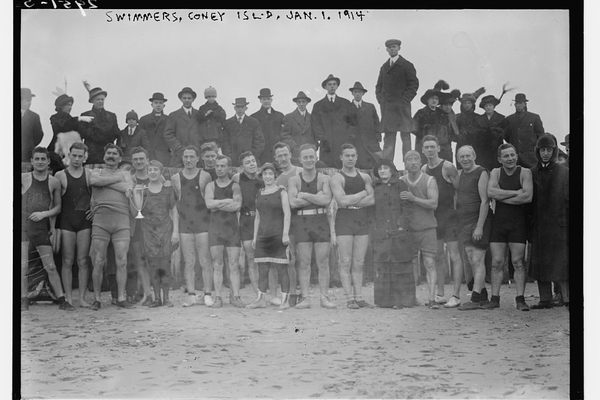

The Chitlin Circuit’s enduring mystique owes much to the fact that its early history is relatively undocumented. The circuit’s early roots can be traced to vaudeville, the nickname for a type of popular entertainment that emerged in the 1800s, as well as the venues where such performances took place. The term originated in France but migrated to the United States. Run by whites, vaudeville’s comedies, dance routines, minstrel shows, musical acts, and staged plays were more about pleasing the masses rather than high art. In the late 1800s, B.F. Keith and E.F. Albee are generally recognized as the first people to organize a standardized system of venues in the United States where talent was booked for specific engagements at vaudeville venues.

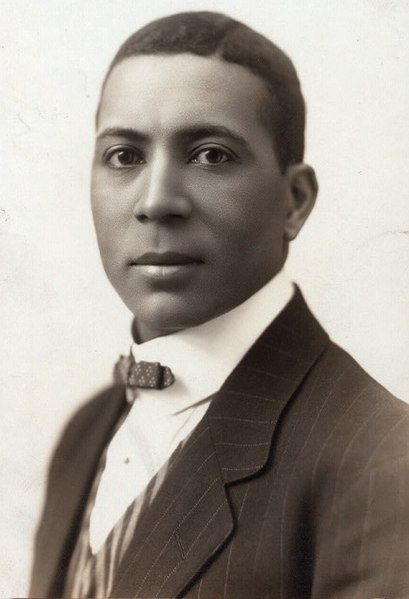

Unsurprisingly, African American performers languished in an industry controlled by white booking agents. They had little leverage—Jim Crow segregation limited where they could perform and safely travel. In 1911, an African American man named Sherman Dudley created his own theatrical touring company, purchased numerous entertainment venues, and unionized African American artists. Dudley’s circuit thrived for several years until the white-owned-and-operated Theater Owners’ Booking Association (TOBA) was formed in 1921. TOBA dominated the southern states market and squeezed out competition from Dudley. Seeing the writing on the wall, Dudley merged his circuit into TOBA and eventually managed the company’s Washington, D.C. office. TOBA dissolved in the 1930s, primarily because of the Great Depression and alleged mismanagement by the main principals.

After TOBA’s demise, Denver and Sea Ferguson, two African American siblings based in Indianapolis, Indiana, formed the Ferguson Brothers Agency, whose national network of venues directly booked performers. This was the origin of the Chitlin Circuit. Even after the Fergusons’ thriving agency shut down in the late 1940s, other circuits evolved, sometimes relying on the longstanding and personal relationships that Black entertainers had with Black-owned venues. They often lacked the organization and national reach of what the Ferguson Brothers had created, but they still gave Black creatives regular access to Black audiences.

The circuit meant different things to different people. For many Black artists, the circuit recalled the hardscrabble life that legendary blues singer “Little” Milton Campbell, Jr., shared with Living Blues magazine. “I don’t know who started that phrase, but I think that they were talking about places such as I played last night,” Milton said in an autumn 1974 interview. “The kind of places that will keep you eating, will keep you making a decent buck, if you’ve got something on the ball, whether you’ve got hit records or not. If you’re hot—if you got hot records, you’re going to work. And if it gets big enough, you’re able to work anywhere. And in this business, if you know the right people, you can be promoted into the upper-class and the better joints.”

Patti LaBelle echoed the “hard times” vibe of the circuit where she earned $9 a week early in her career by singing at churches and run-down establishments. “It wasn’t even the chitlin circuit,” LaBelle derisively told the Philadelphia Inquirer in a 1984 interview. “It was sardine houses.” Apparently, there were lower places to go than the Chitlin Circuit, but entertainers understood it was a rite of passage. Other Black artists, such as Bobby Massey of the O’Jays, a popular rhythm and blues (“R&B”) group in the 1970s, saw the circuit through a racial lens. “The chitterlings circuit is any place white people don’t go to see black people,” Massey said in a 1977 newspaper interview.

“Chitlin Circuit,” as a coined term, floated around in Black culture for decades until it went mainstream in the late 1960s thanks to syndicated newspaper interviews with Black artists such as B.B. King, Lou Rawls, and Ike and Tina Turner. Rawls vividly described performing in cafés and beer joints where he honed his attention-grabbing entertainment skills. “I started talking [before singing a song] because it was the only way to get people’s attention. For years I played night clubs, working the chitlin circuit. These clubs were very small, very tight, very crowded, and very loud. The only way to establish communication was by telling a story to lead into a song.” Rawls’s bluesy opening soliloquies became one of his trademarks.

Attempting to achieve the same goal, an accomplished tap dancer named Saxie Williams, by then in his late 70s, reminisced in a 1980 newspaper interview: “I worked the so-called chitlin circuit, which were black nightclubs. I did a novelty act where I’d pick up tables and chairs with my teeth and dance. It was sensational and I didn’t need a partner. I did that act for about 10 years.”

Not everyone waxed nostalgically about the circuit. Actress Tichina Arnold, known for her role on the popular television show Martin, said in a 2003 syndicated newspaper article: “No matter how you presented it and explained it to me, I’m like ‘That’s the Chitlin Circuit and I don’t want to do it … [n]ot because it’s theater (that requires a long commitment and prevents screen actors from taking higher-paying jobs), but because of what came along with it. There were a lot of actors that had bad experiences, and it got a bad name for itself.” Other artists spoke of being underpaid, and sometimes not paid at all after a performance.

To understand how this network got its nickname, one needs to understand a thing or two about chitterlings. Chitterlings are animal intestines, usually the small intestines, cooked and eaten. African Americans spell this dish in various ways, but “chitlin” and “chitlins” are the most common. As African American newspaper columnist John Robinson once wrote, “Chitlins are as black as the blues, as funky as the bump, as ethnic as Cape Cod turkey and Wonder bread (Yankee), lox and bagels (Jewish), or corned beef and cabbage (Irish). To have chitlins at your family gatherings is to declare yourself so black, culturally speaking, that compared with you, Aretha Franklin seems like Katherine Hepburn.”

Over time, chitlins secured iconic status in African American cuisine because of their connection to the experiences of enslaved people. One of the high points of the year in the antebellum and agricultural South was the hog-killing. Pigs are easy to raise, and were the most prevalent source of meat in the South. During antebellum hog killings—held when the weather cooled in order to reduce spoilage—hundreds of hogs could be killed, and that work was usually and forcibly tasked to enslaved African Americans. Even after Emancipation, neighboring plantations and farms often pooled their financial and labor resources to efficiently slaughter, process, and preserve as many hogs as possible. After the slaughtering, much of the pig was either pickled, salted, or smoked for preservation. This included highly valued cuts of meat such as bacon, hams, and shoulders, and variety cuts like ham hocks and pigs’ feet. This was a feature of rural English life transplanted to the American South by British colonists.

After all that hard work, it was time to celebrate. The slaveholder marked the occasion with a feast, and everything that couldn’t be preserved was cooked and consumed. Ephemeral delicacies like chitterlings made their way on the table, except when used as a casing for sausage. In the African American context, chitterlings now became chitlins. Traditionally, and hopefully, chitlins are meticulously cleaned and either stewed in a seasoned broth or dipped in batter and fried. Because it was tied to special occasions, chitlins have long been considered a delicacy. To this day, chitlins regularly appear on restaurant menus and on holiday tables in private homes.

The slaveholders’ practice of saving the prestigious cuts of meat for preservation for their household and leaving everything else presumably for immediate consumption of the enslaved has fueled the widespread belief that chitlins were something that “white people didn’t want.” Even though plenty of white southerners ate chitlins, and still do to this day, the idea that chitterlings were wholly created for enslaved African Americans has died hard.

This narrative is partly true and partly false. Much of the writing about chitlins and the Chitlin Circuit describe the dish, since it’s made from intestines that are little valued in much of the United States, as the part of the animal that white slaveholders did not want. But this is a myth—Americans and Europeans have held chitlins in high esteem for generations.

That tale begins with deer hunting in the medieval period, when it was a pastime reserved for European royalty and aristocracy. Poor people could only hunt under severe restrictions and usually with the permission of the ruling authority. After the hunt, they relished the internal organs, also known as the innards or offal, including the heart, intestines, liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen, and sweetbreads. In time, the chitterlings of domesticated animals were more widely consumed by the wealthy.

As late as the 1700s the intestines of cows and pigs were a high-end food featured in British cookbooks, particularly The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse, which was published in 1747. In that highly influential cookbook, Glasse includes a recipe for beef chitterlings that is a clear relative of French chitterling sausages called andouillettes. Glasse also informs her British readers that the beef chitterling recipe is a summer-months substitute for the pork version of the dish. Why? Because hog-killings, as described above, were saved for the fall and winter months.

The chitlins-as-unwanted-leftovers belief has led to two enduring and diametrically opposed narratives in Black culture. For many, chitlins symbolize edible white supremacy, and they are bewildered that African Americans continue to eat this dish given its history, and that it must be cleaned of feces and creates a distinctive, arguably disgusting, smell when cleaned and cooked. For others, chitlins are a triumphant delicacy: Black cooks took the very worst things that slaveholders forced upon them and made it delicious.

These varying perspectives have made chitlins the most polarizing dish in the African American cuisine known as “soul food.” You’re not going to meet someone “sitting on the fence” about chitlins. They either love them or hate them. Reminisces of numerous Black entertainers make clear that chitlins were not always on the Chitlin Circuit menu. Neither was being paid in chitlins a uniform practice. Yet enough people, through shared experiences, connected life on the circuit to the southern delicacy, and the nickname stuck.

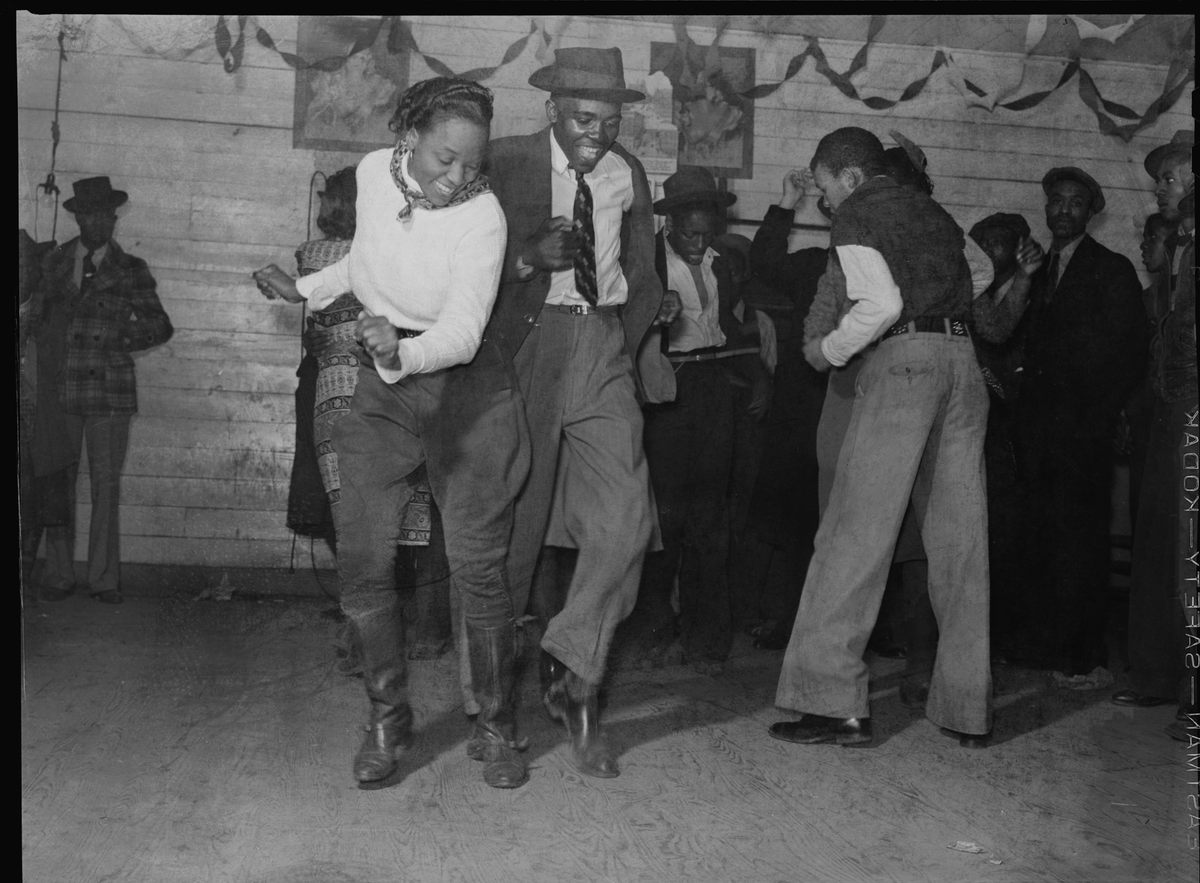

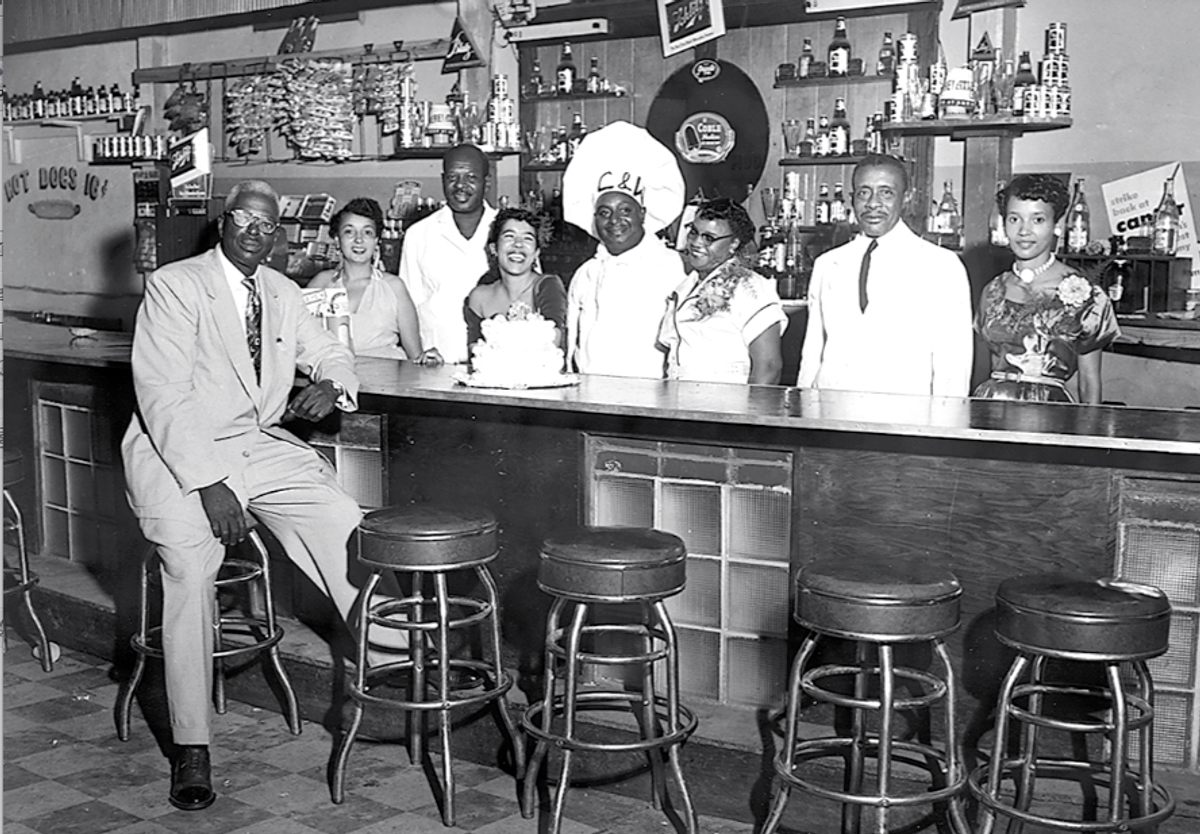

The Chitlin Circuit’s venues ranged from rudimentary juke joints in rural areas to nightclubs, restaurants, and higher-end theaters in larger cities. For decades, the circuit was strongly associated with blues, jazz, rock, and soul musicians and singers such as Billie Holiday, B.B. King, Denise LaSalle, and James Brown. Entertainers felt they had “made it” if they performed at one of the highly coveted venues: Atlanta’s Royal Peacock, Baltimore’s Royal Theater, Chicago’s Regal Theater, Detroit’s Paradise Theatre, Harlem’s Apollo Theater, and Washington, D.C.’s Howard and Lincoln Theaters.

Since the 1990s, Black entertainers and media have expansively interpreted The Chitlin Circuit to include more media genres and platforms and as a throwback to its vaudeville roots. Its geography is not limited to the American South and the Northeast, but now includes the entire country. The type of entertainment featured has expanded to author presentations, comedy, gospel music, plays, poetry, spoken word performances. Some even argue that media outlets such as radio, television, and digital platforms catering to predominantly Black audiences should constitute a “Chitlin Circuit 2.0.”

Perhaps the most compelling origin story for its name is that chitlins are a perfect metaphor for the plight of the Black artist getting started in any creative endeavor. Chitlins are very labor intensive to prepare because they take a long time to clean and cook. One must also clean pounds of chitlins to get an appreciable amount to serve. Is that experience too far removed from the performer who hones their craft for years, out of the limelight and sometimes in terrible conditions, all in pursuit of stardom? In both cases, that hard work seems hardly worth it until one experiences the wondrous and soul-satisfying results. Little Milton gave a beautiful, bluesy benediction to this subject when he expressed to Living Blues magazine: “Some of us are still grinding. I’ve been able to work whether I’ve had records, hot or not. To be truthful to you, I owe everything that I have, popularity and everything, to the chitlin circuit.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook