Tattooing in the Civil War Was a Hedge Against Anonymous Death

Hidden tattoos captured soldiers’ pride and patriotism, but also had a practical use.

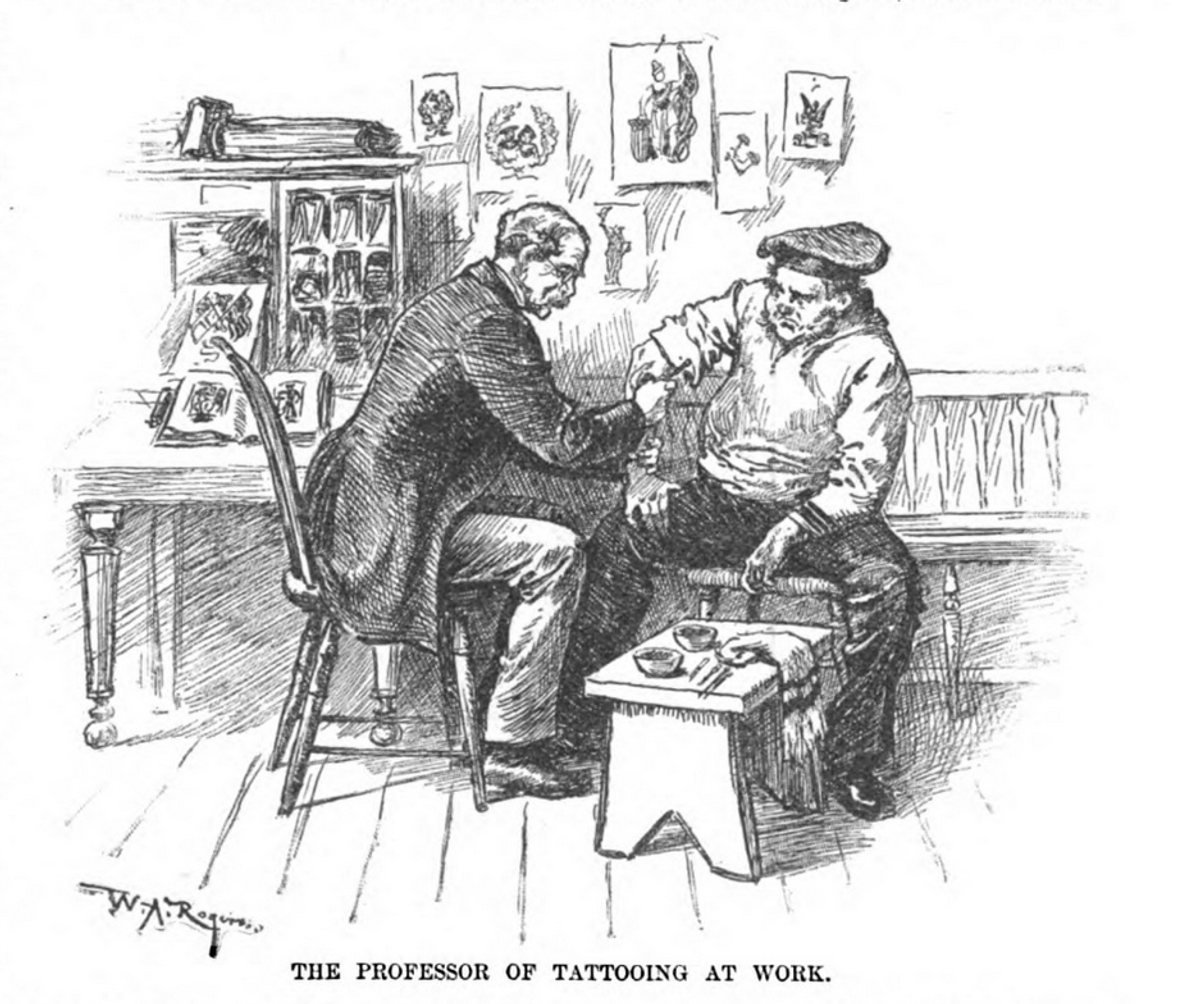

In 1876, on Oak Street between Oliver and James, a long-lost block of lower Manhattan that now lies underneath a housing project built in the 1950s, a New York Times reporter found the sign he had been looking for—“Tattooing Done Here.” Inside the shop, which he described as “a tavern with a well-sanded floor,” he found Martin Hildebrandt, the most famous tattoo artist in 19th-century America.

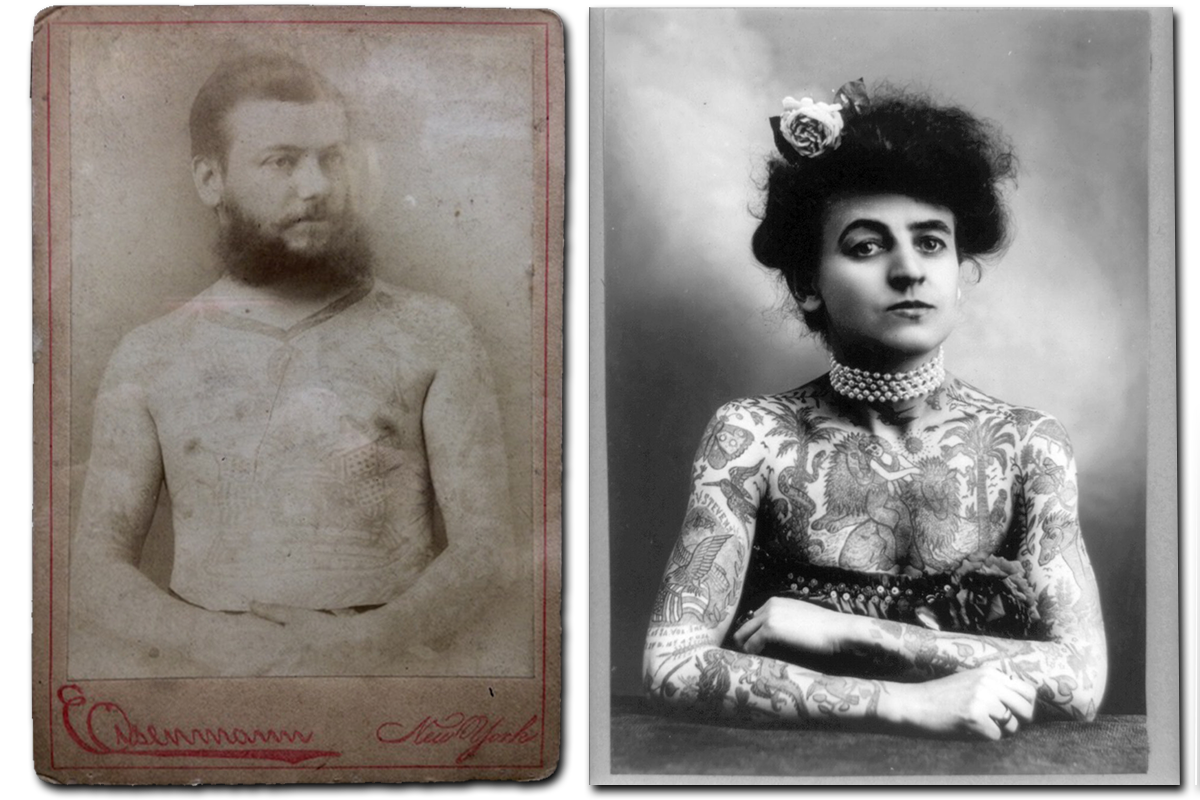

Short and talkative, with a crucifix inked on his back, Hildebrandt was happy to tell reporters about his unusual trade. As far as historians can tell, he was the first person in the United States to set up a permanent shop as a tattoo artist, at a time when body art was still a hidden practice in the country, associated with circus performers, faraway cultures, sailors, and native tribes.

But quietly Americans of all sorts were getting tattoos. Secret societies such as the Masons and Good Fellows had their members inked with special signs, and as Hildebrandt would tell the Times reporter, he’d worked on people from high and low society—from mechanics and farmers to “real ladies” and gentlemen. During the Civil War, when he’d served in the Union’s Army of the Potomac, Hildebrandt had initiated at least a brigade’s worth of soldiers into the culture of ink.

“During the war time I never had a moment’s idle time,” Hildebrandt told the reporter. “I must have marked thousands of sailors and soldiers.”

Hildebrandt is the only tattoo artist known to have spoken openly about creating Civil War tattoos. But other accounts and historical records hint that the practice of getting inked became more widespread during the war. “It probably means there were other tattoo artists; we just don’t know who they were,” says Michelle Myles, the co-owner of Daredevil Tattoo, a Lower East Side shop with its own museum collection of antique tattooing memorabilia. For the first time in American history, tattooing was becoming part of mainstream American culture.

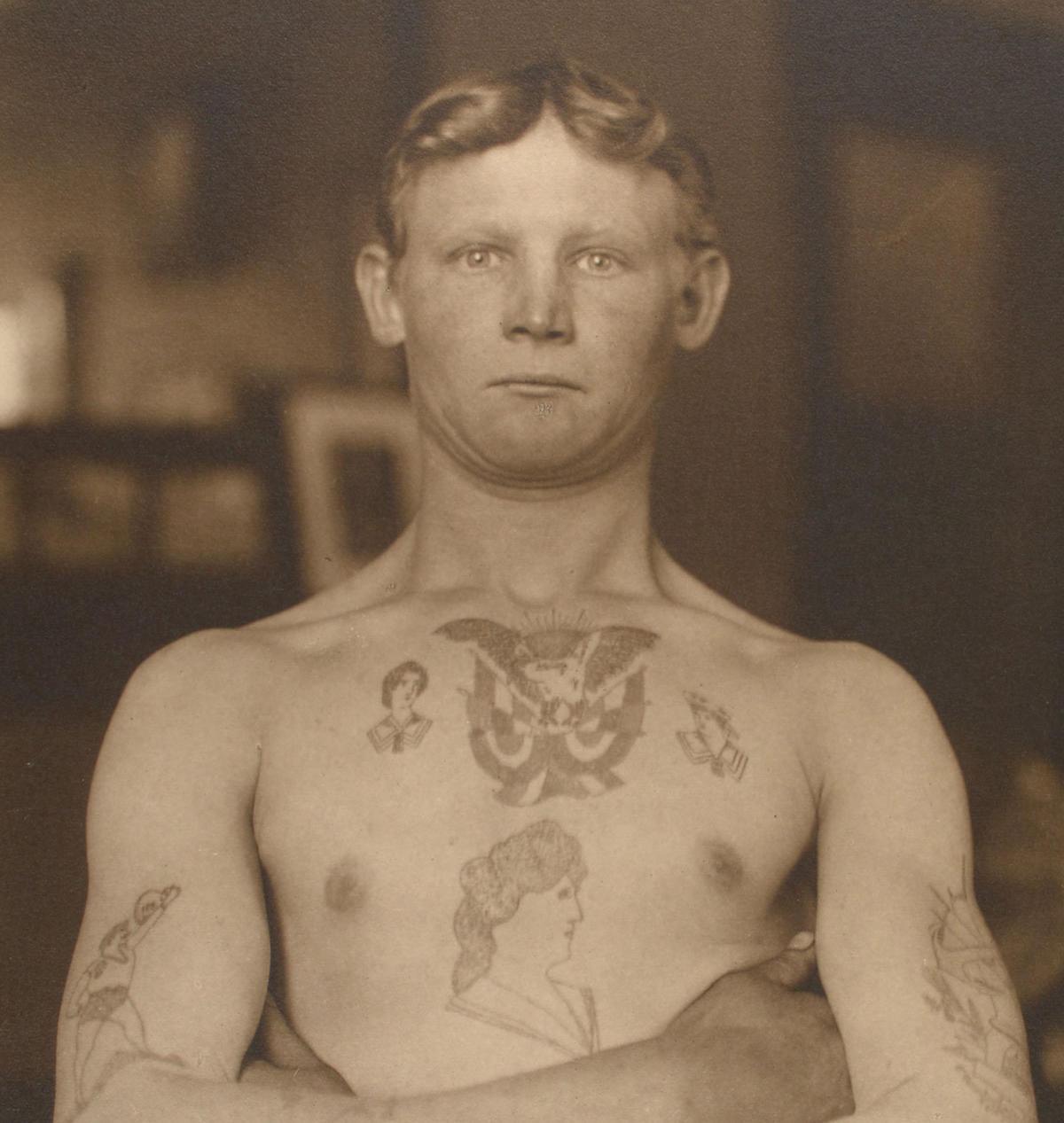

The Civil War helped tattooing begin a transition from the military to wider society, and ushered in the style of classic tattooing unique to America. Tattooing had long been widespread among sailors, but during the war men who would never have considered getting a tattoo before wanted a way to show their allegiance to their cause and to identify themselves in the event of death.

“Your stripes can get torn off in battle,” says Paul Roe, a tattoo historian. “Tattoos can’t.”

Tattoos have a long history as a means of identification in the military. In ancient Rome, mercenaries were marked with a permanent ink made from acacia bark, corroded bronze, and sulphuric acid to help in identifying deserters. Around the fourth century, the Roman military had a standard operating procedure for tattooing—a recruit would not be tattooed right away, but would “first be thoroughly tested in exercises so that it may be established whether he is truly fitted for so much effort,” the writer Vegetius noted. Even in the military, tattooing was a deliberate choice, not to be rushed into.

In the event of a soldier’s death, a tattoo could be a powerful tool for identification. During the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the defending king, Harold II, was disfigured beyond recognition while fighting the invading Normans, led by William the Conqueror. Edith Swannesha, who spent her life as Harold’s companion and is sometimes called his common-law wife, was summoned to identify his body. She was only able to recognize him based on his tattoos—the words “Edith and England” across his chest.

But despite the royal and military history of tattoos, for many centuries there was a taboo attached to the practice. Tattoos were used to mark slaves, criminals, and gladiators, and the Latin word “stigma” was used interchangeably to mean tattoo, brand, or scar—any permanent mark left on a person’s skin. In the United States, tattooing was associated with native tribes; when French and British traders met native people, they often recorded the markings on their bodies, instead of their names, in trading logs. This practice continued when Europeans recruited tribes as allies during colonial wars. For American settlers, tattooing would have been most closely associated with Native Americans or criminals, and deemed unacceptable for “civilized” people.

But that first started to change during the Revolutionary War. American sailors decorated themselves with symbols of their newborn country—the “goddess” Columbia, the face of George Washington, the American flag. For these sailors a patriotic tattoo served both as personal and group identification. “It was the old striving to frighten the enemy with magic representations of the tribe’s invincibility,” tattoo historian Albert Parry writes.

With the onset of the Civil War, these patriotic themes gained in popularity and began to shift from sailors to land-bound infantry. By this point in history, tattooing was not as uncommon as it seemed. There are accounts, for instance, of Irish workers bound for naval ships, who were already tattooed but had no previous maritime experience. At least among the Irish working class in New York, tattoos were not restricted to the military, navy or otherwise, and during the war the stigma began to lift.

There’s a story about Hildebrandt’s work in the Civil War that comes up in almost every account. He fought for the Union, but, people say, he crossed battle lines as an artist. The story, however, doesn’t seem to be true.

Myles, the Daredevil Tattoo owner, has looked deep into Hildebrandt’s history and tracked down every scrap of evidence she could find about his life. She has never found a primary source for that tale, but it endures, perhaps because it adds a touch of humanity to an inhuman time. Part of the myth, according to the Roe, the tattoo historian, is that Hildebrandt would charge soldiers in the South less, because they got paid less—a kind gesture in a grave situation. “I put the name of hundreds of soldiers on their arms and breasts,” he told a reporter in 1882, during another interview in that shop on Oak Street, “and many were recognized by these marks after being killed or wounded.”

In addition to identification and patriotism, tattooing during the Civil War was used to memorialize the experience of war and the lives of fellow soldiers. Much like the sailors who pioneered tattooing before them, these soldiers wanted to honor the memories of fallen comrades, show regimental pride, and demonstrate their love for their homelands. “A sailor may not wear his heart upon his sleeve, but he does wear it upon his chest,” Eleanor Barns of the Seamen’s Institute, an agency for mariners affiliated with the Episcopal Church, told Parry, the historian.

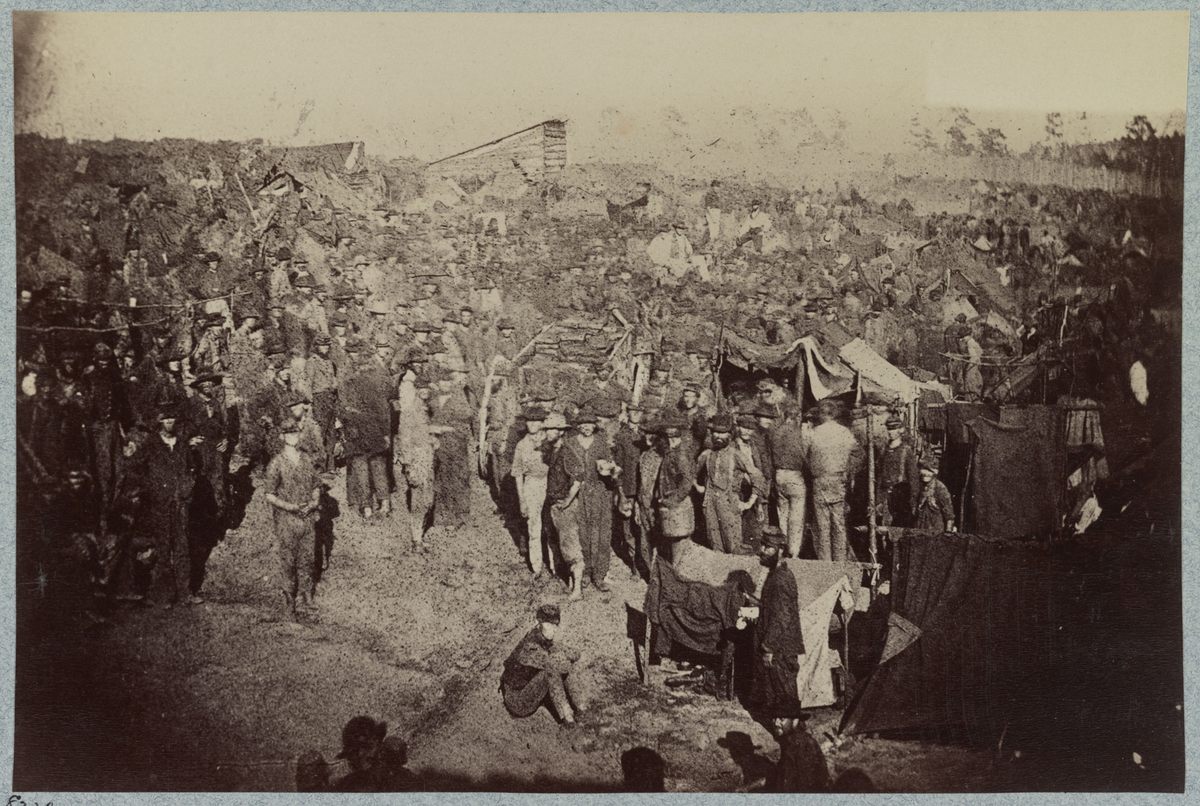

Tattooing can be excruciating, and in the Civil War methods were relatively primitive and conditions less than sanitary. After Robert Sneden, a mapmaker, illustrator, and Union soldier was captured one foggy night near Brandy Station, Virginia, he was taken to the notorious Andersonville POW camp, where a sailor named Old Jack tattooed the prisoners using “six to eight fine needles.” The going rate was $1 to $5 (anywhere from about $30 to $150 in today’s money).

“The ink is pricked into the flesh on arm or leg on the design there,” Sneden wrote in his memoirs. “The jabbing takes an hour or more. The arm soon swells up and inflames, which is painful for a few days only.”

Hildebrandt’s tattoo method was similar, and involved binding together a handful of #12 needles, roughly 0.35 mm in diameter, “in a slanting form, which are dipped as the pricking is made into the best India ink or vermilion [sic],” the Times reported when visiting his shop. “The puncture is not made directly up and down, but at an angle, the surface of the skin being only pricked.” Colorants could be made up of ink and wet gunpowder. After the tattoo was done, any excess blood and ink was washed off with water, urine (it’s sterile!), or alcohol, usually either rum or brandy.

Some of the most vivid accounts of Civil War tattooing come from works of fiction, written after the war but based heavily in fact. In 1887, Wilbur F. Hinman, who’d been a lieutenant colonel in the 65th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, published the novel Corporal Si Klegg and His “Pard”, in which he “attempted to present a truthful account of soldiering.” In the book, he described tattooing as a ubiquitous practice.

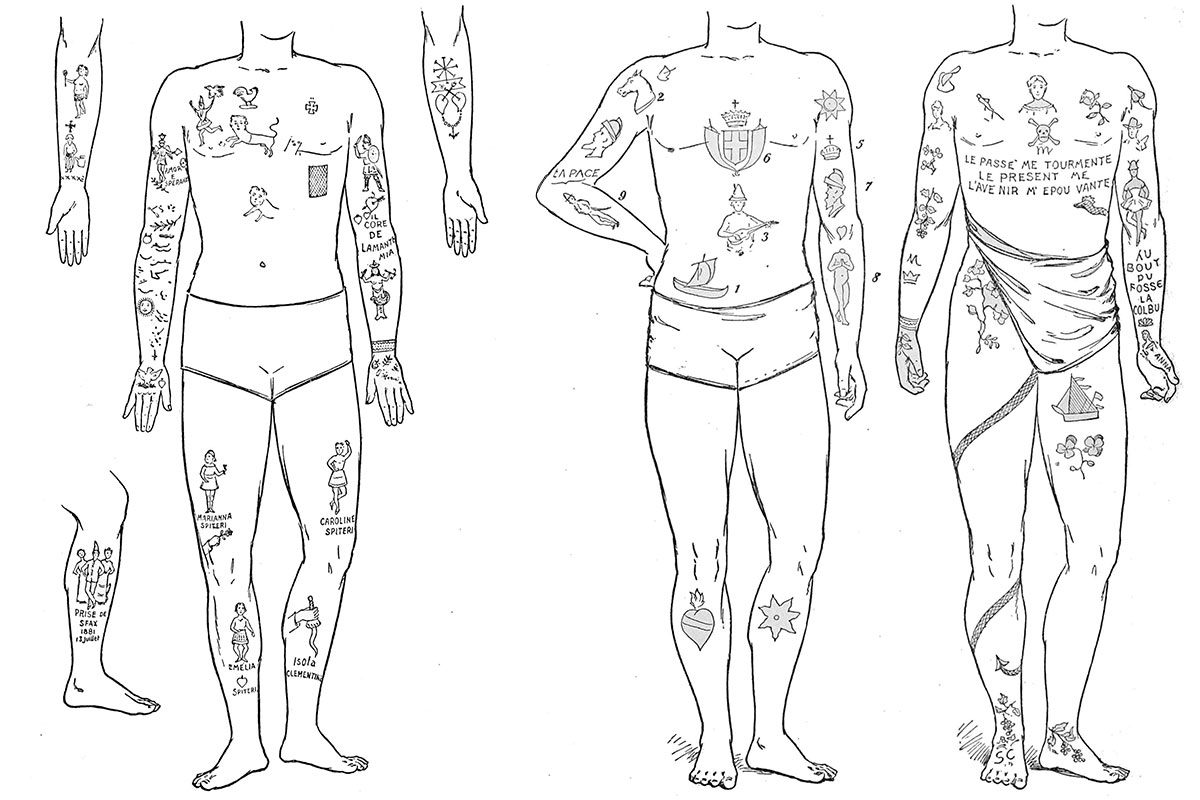

“Every regiment had its tattooers, with outfits of needles and India-ink,” Hinman wrote, “who for a consideration decorated the limbs and bodies of their comrades with flags, muskets, cannons, sabers and an infinite variety of patriotic emblems and warlike and grotesque devices.” Many a soldier, according to Hinman, had his name, regiment, and residence inked for identification. “It was like writing one’s own epitaph, but the custom prevented many bodies from being buried in ‘unknown’ graves,’” he wrote.

Sneden, the POW, described tattoos of “flags, shields, and figures,” along with “anchors, hearts, men’s names and regiments” and “crossed flags and muskets.” A sergeant reported that by 1864 it was becoming popular in his unit to have a tattoo of a goddess, Venus, or some other “half-covered women” as a memento of the war.

One ship’s crew reportedly had stars tattooed on their foreheads to celebrate victories, but such memorials could be dangerous provocations in future battles. In another account from the war, a cannoneer is killed because he has the words “Fort Pillow”— the site of a massacre of Union troops—inked on his arm. “As soon as the boys saw the letters on his arm, they yelled ‘No quarter for you!’ and a dozen bayonets went into him and a dozen bullets were shot into him,” writes amateur historian Mark Jaeger in Civil War Historian.

Though tattooing had become a widespread practice, after the war publicly visible tattoos were still an oddity. In the 1880s, Hildebrandt’s tattooed daughter toured as part of a circus troupe. But beneath their clothes, many men held the marks from the war—voluntary scars to commemorate a shared trauma, claims of individuality in the face of mass death, assertions of humanity that couldn’t be taken away.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook