This Artist Makes Mesmerizing Collages From Produce You Can’t Find in Supermarkets

Celebrating the diversity of tomatoes, corn, and other crops.

“Those were just drops of honey, they were so incredibly sweet,” says German artist Uli Westphal. “Those were really magnificent. And they were tiny, like the red currant berry.”

The tiny fruit in question isn’t a ripe raspberry or cranberry. It’s a tomato. The red currant tomato, to be precise, a wild counterpart of the larger, more commonly cultivated Roma and beefsteak varieties sold in supermarkets. The dainty red currant is one of the many unique cultivars featured in the Lycopersicum series, Westphal’s sequence of collages of tomatoes arranged from bright-green to red-black, from multi-lobed to currant-tiny, all photographed against a stark white background.

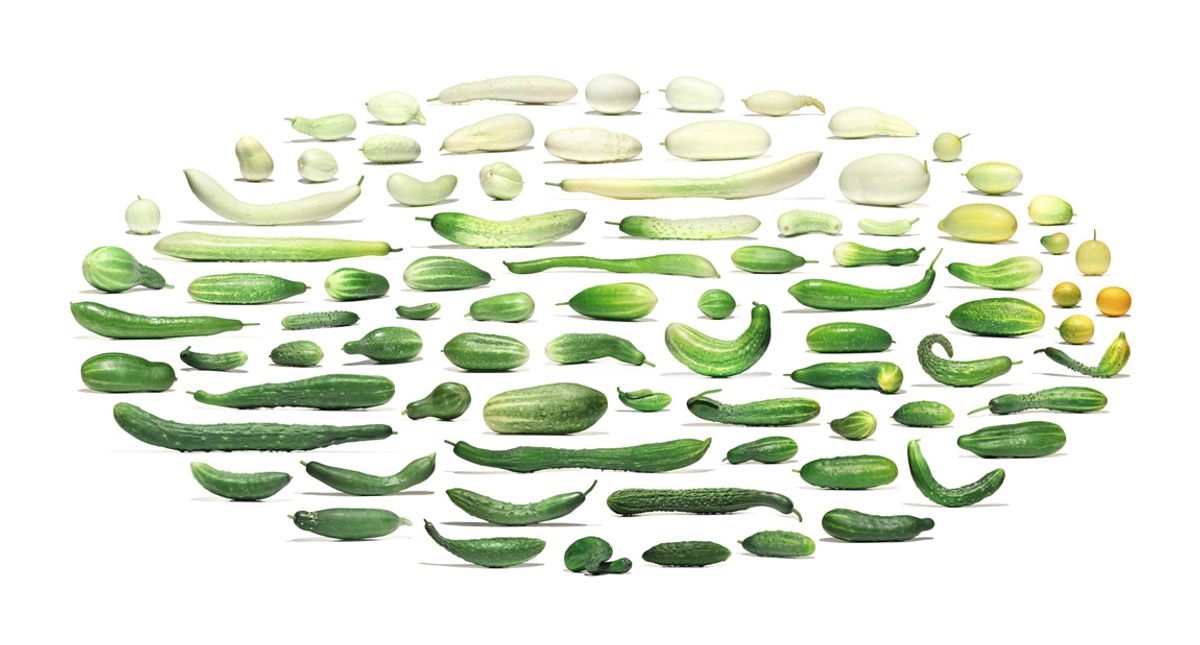

Tiny tomatoes aren’t the only unique produce Westphal has photographed over the years. A Berlin-based artist dedicated to using his camera to document agricultural biodiversity, Westphal has been discovering, photographing, and tasting unique produce since 2006. In 2010, he began The Cultivar Series, a constantly-expanding collection of collages featuring stunning rainbows of produce, from pears to corn, arranged painstakingly according to species.

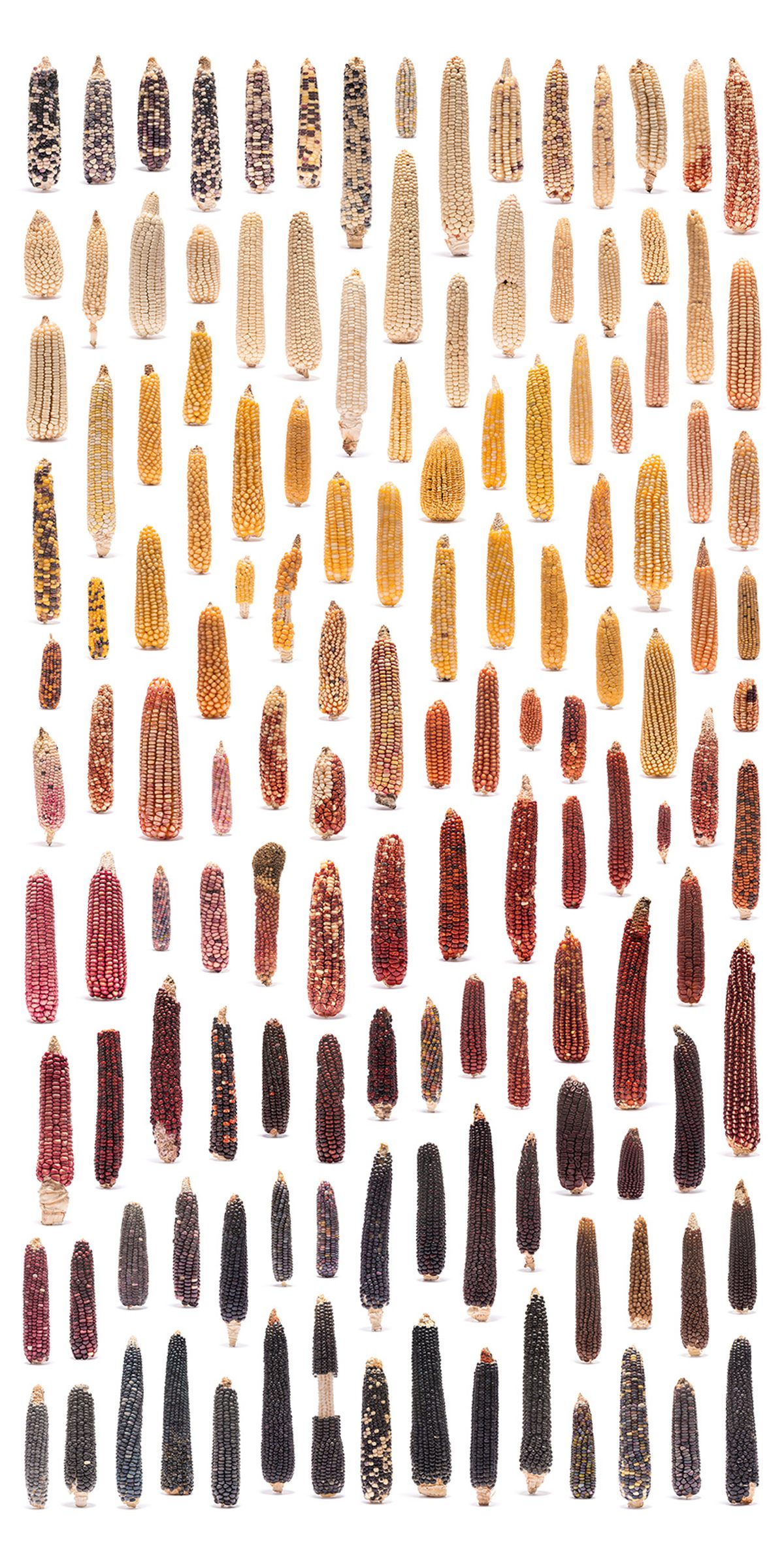

Almost taxonomic in their precision, Westphal’s images aren’t just beautiful. They’re also documentation of the vast diversity of cultivated crops that critics of industrial agriculture feel monoculture, or the standardized cultivation of one variety of a plant, has left behind. Some scientists worry that the growing standardization of the global food supply, evident in the increasing cultivation of a limited number of crops, could have a negative effect on food security and human health.

Concern about food security is a central motivation of Westphal’s work. He also worries that declining biodiversity limits people’s visual and taste experiences of food, and threatens valuable cultural knowledge. Developed over millennia of careful breeding, cultivars are a living record of human beings’ relationship with the environment.

“Especially in agriculture, there has been some sort of coevolution between humans, plants, and animals that has happened over thousands of years,” says Westphal. “Everything we eat, it’s still a biological organism, but it’s also something that we have cared for and that we have shaped.”

This passion for produce inspired Westphal to begin photographing fruits and vegetables in 2006. Intended to document the unique, sometimes otherworldly diversity of produce shapes, Westphal’s Mutatoes series celebrated the “ugly” fruits and vegetables unlikely to be sold at supermarkets. Soon, Westphal became interested not just in unusually shaped produce, but in the vast diversity of cultivars that yield it.

Now, Westphal scours seed banks and farmers’ markets in search of unique cultivars. When he spots a new specimen, he photographs it at precisely the same angle, with exactly the same lighting and white background, as the others in his collection. He then digitally adds the image to a collage of similar fruits or vegetables in a hypnotic and ever-expanding visual record of human agricultural achievement. His collection thus far includes corn, tomatoes, beans, cabbage, sweet potatoes, and peppers, among others.

Westphal doesn’t just photograph this produce. When he can, he takes a sample and cooks with it, or collects and plants its seeds. At one point, his greenhouse held over 60 distinct varieties of cucumber.

While the sheer beauty of vibrant pink corn and bulbous green tomatoes is entrancing enough, each of Westphal’s collages also reveals stories of the farmers who developed the cultivars and the communities who enjoy them. For Westphal’s 2018 series, Zea mays, he visited two seed banks, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico and Native Seeds in Arizona. The banks preserve tens of thousands of unique cultivars in cold storage, conduct workshops with growers, and provide seeds to help farmers across the world grow more diverse and sustainable crops.

Westphal photographed the banks’ stunning collections of corn, including many cultivars that were developed by people indigenous to the North American deserts. He recalls Hopi blue corn, whose indigo ears were bred to thrive despite the parched climate of the American southwest. Planted more than a foot beneath the ground, the seeds soak in existing groundwater before pushing up through half a meter of soil to the sun.

This aura of perseverance animates Westphal’s work. His two-headed tomatoes and gnarled ears of corn reveal that even those plants that differ from our preconceived notions of beauty are works of art. When talking about the most wondrous fruits he’s ever seen, Westphal mentions the Buddha’s hand citron, a yellow-green citrus fruit whose tentacle-like strands curve creepily from the branch. But he also mentions the lowly citrus bud mite, a parasite that causes lemons to grow in lumpy, twisted shapes. While farmers may call the mite a pest, Westphal calls it an artist.

“The parasite is really working as a sculptor,” Westphal says. In other words, it makes beauty out of the quirks of agriculture, just like Westphal himself.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook