Syrian Refugees Are Learning Stonemasonry to Rebuild Their Country

The apprentices hope to restore damaged buildings and monuments after the war ends.

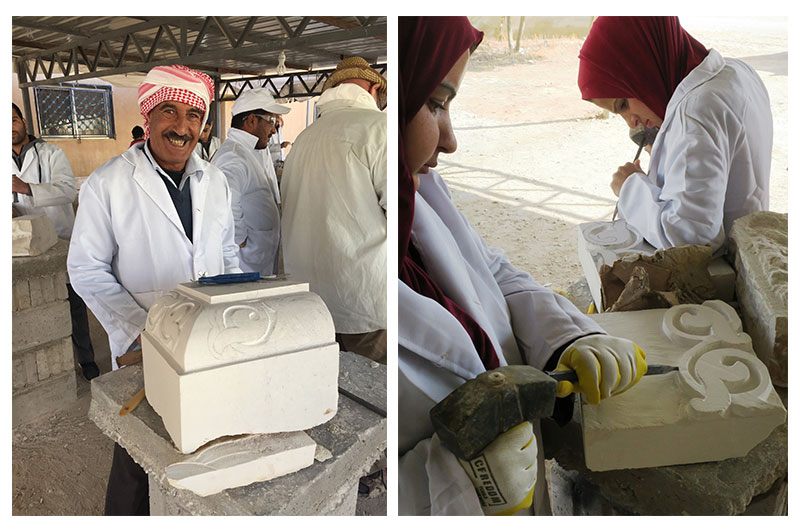

In Mafraq, Jordan, a group of Syrian refugees is studying the art of stonemasonry. They gather each day at 5 a.m. to learn how to hammer pieces of rock into the kinds of beautiful ornaments that once adorned the buildings of Aleppo, before the war reduced them to rubble.

The center where they train is just 12 miles south of the Syrian border. It is close enough that you can sometimes hear the low rumbling of bombs across the border. In time, these refugees hope to cross back over this border and start to restore their country’s cultural heritage.

The 42-week course began in September 2017. It is run by the World Monuments Fund, in partnership with the Petra National Trust, and is managed by a small team of architects with a background of conservation in the Middle East.

“In the future, it may be possible to return to Syria,” says Mahmoud Rafeeq Al Qasem, 40, a former timber trader from Homs. “There were many things that were destroyed; many monuments have been damaged. I could take part in rebuilding my country.”

Al Qasem is one of the 28 refugees taking part in the program – a group that includes both men and women. There are also seven Jordanians, included to combat the perception that local people are being shunned in favor of the country’s massive influx of Syrians.

This somewhat disparate collection of people—among them a former Syrian Army soldier, a taxi driver, a housewife, and a pipeline construction worker—spend their days either absorbing theory in a classroom or chipping away at blocks of limestone in an open courtyard. They study geometry and visit the ancient sites of Jordan, such as the ruins of the Roman city of Jerash, take lectures from local professors on geology and the history of Islamic architecture, and learn how to craft ornamentation out of rock and clay.

Since the war began in 2011, more than 5.6 million people have fled Syria. In Mafraq alone, there are almost 80,000 registered Syrian refugees, with another 80,000 at the Zaatari refugee camp on its outskirts. Those fleeing the country include doctors, teachers and engineers, but also stonemasons. They were already in short supply before the war, and their flight will complicate the challenge of rebuilding Syria’s historical architecture even after it becomes possible to re-enter the country.

“Before the war, we found it was straightforward enough to find professionals—architects, engineers, even conservation professionals—mostly outside of Syria, but also in Syria,” says Stephen Battle, who manages the training program. “But the thing we found the hardest was to find craftspeople—people with the skills in their hands for the conservation work and restoration work we were trying to do,” Before the war began, Battle had been working on the Citadel of Aleppo, a 13th-century fortress that once guarded the city.

“It raises the question of, if it was that difficult before the war to find skilled craftspeople, then what’s it going to be like when bullets finally stop flying? Given all the population displacement and loss of life, combined with the huge amount of extra work that has to be done, how does that equation square itself out?”

It would not be the first time that conservators have struggled to restore a country’s historical character following a conflict or disaster. In Iraq, for instance, many people in the cultural sector were Christian, and left in the aftermath of the war to avoid persecution.

“Our experience in Iraq was that there was an enormous number of well-trained archaeologists, many of whom are still in the country, but there is just not an archaeological conservator virtually to be found. That sector picked up and left,” says Lisa Ackerman, executive vice president of the World Monuments Fund.

Conservators are concerned that the character of Syria’s cities, with its ornamented limestone buildings and geometric patterns, should be maintained during any rebuilding efforts. The redesign of Beirut, following its destruction during the civil war in Lebanon, was criticized for transforming a bustling and charismatic city into a ghost town of slick glass buildings, designer stores and empty apartments. By contrast, following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the World Monuments Fund rushed in to protect the country’s post-colonial “gingerbread houses.”

Much of the training that the refugees are undertaking is based on photographs of buildings in Aleppo, taken before they were destroyed. But there will be no shortage of sites where a Syrian stonemason could apply their skills one day, including places like Damascus Old City, Bosra, and the Lady of Saidnaya Monastery.

Even if the opportunity to return to Syria doesn’t emerge any time soon, such skills are transferable, leaving them equipped to work on modern buildings where stone is used as cladding, for instance, as well as historic monuments. The program will wrap up this September, when the World Monuments Fund hopes to recommence with a new group.

Amid the disruption and dislocation faced by these refugees, stonemasonry has offered an opportunity to rebuild not only their history but also part of their identity.

“My life has benefited a lot from joining the course, and praise God I see myself developing from where I was to where I am now,” says Awaish Jumaa Al Jibra, 28, from Aleppo. “We’ll carry on using the skills when we go back to our country, to our neighborhood in Aleppo after the war, after all this.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook