Dark Crystal: The Secrets of Swarovski

A Swarovski crystal. (Photo: Alexander Baxevanis/flickr)

A Swarovski crystal. (Photo: Alexander Baxevanis/flickr)

There are gems, there are crystals, and then there’s Swarovski.

The improbably successful Austrian crystal manufacturer is the epitome of shopping mall luxury. It sounds foreign, exclusive, precious. Yet you can buy a pair of Swarovski earrings from Amazon for $17.60. The same total carat weight in diamonds, in a very similar setting, would cost you somewhere north of $5,000, depending on quality and provenance.

Swarovski makes glass and yet the company has managed to create for itself a brand that carries weight in the luxury world, something no other manufacturer of non-gems has ever even tried. How in the world did that happen?

Swarovski, which celebrates its 120-year anniversary this year, is a steward of a centuries-old Bohemian tradition, making use of natural resources in the Czech Republic and Austria. It’s a phenomenally innovative design studio and an impressively creative chemical laboratory, all in one. And, of course, it’s the beneficiary of absolutely genius marketing.

Swarovski doesn’t talk about their process. They won’t tell anyone what they do to the glass, how they make it. But everyone agrees that Swarovski’s lead glass is the best that’s ever been made.

A kind of glass Bambi. (Photo: Politikaner/Wiki Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

“Glass-making, of course, is a very very ancient technique,” says Stefanie Walker, a jewelry historian who works for the National Endowment for the Humanities and teaches at the Bard Graduate Center (among other places).

To talk about Swarovski, she says, we have to first talk about sand. Sand is primarily composed of silica, which properly is called silicon dioxide. You make glass by melting sand and other chemicals. Sand melts at 3090°F, so some of those chemicals, as you might expect, are used to lower that melting point to make the whole process a bit easier. Others are used for stability, to ensure the glass won’t dissolve in water, and for various aesthetic reasons.

Glass is not a crystal; as science teachers like to say, glass is a particular type of liquid, so its internal structure is all a jumble. A crystal, like quartz, has a very strict molecular structure that allows it to grow, almost like connecting Lego blocks. To cut a true crystal, you have to “cleave” it, lop it off, at a weak point. To continue the Lego comparison, if you wanted to reduce or reshape a Lego construction, you wouldn’t attempt to break an individual block; you’d have to remove blocks where they connect to other blocks. That’s why gems have a particular array of shapes: creating a spherical diamond has become kind of an engineering challenge, because the crystal simply does not cut that way.

Glass is more like a popsicle. It’ll hold its shape, but you can make that shape whatever you’d like, and can change that shape by melting and reforming it whenever you’d like. Cutting glass can be tricky, but it doesn’t work the same way cutting crystals does.

Outside the company’s headquarters. (Photo: BKP/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Because the key ingredient for making glass is so cheap (free, really) and abundant, glass has a long history. Glass beads, the earliest example of decorative glass, have been found dating back about 3,000 years. But as techniques and technology inches (and sometimes spurts) forward, glass-making has become more and more advanced. Around the 16th century is when glass-making really became an art, if not a totally above-board art. “When you talk about the 16th century, or the Renaissance, you have people talking about fakes, glass fakes, for valuable gems, all the time,” says Walker. But parallel to the development of counterfeit diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds is the concept of glass jewelry for its own sake.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, that concept exploded thanks to a development called glass paste. Previously, glass would be hand-formed by chipping away at it to get the desired shape. That sort of glass was cheaper than diamonds, but still fairly labor-intensive. Glass paste, on the other hand, is the first example of really high-end, beautiful glass jewelry. A French jewel designer named Georges Frédéric Strass in 1724 came up with the idea to mix in a bit of lead with the glass, replacing carbon that had been there before. This had two major effects. Glen Cook, chief research scientist at the Corning Museum of Glass, says: “Lead glass is actually quite easy to melt and shape, in terms of the temperatures needed and the skill required,” though he’s careful to note that it’s still pretty far outside the range of at-home DIY projects. And even better, lead glass has a very lovely sort of shine and luster—almost like diamonds.

Crystal Dome of Swarovski Crystal Worlds, Wattens. (Photo: Zairon/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lead glass, sometimes (and technically incorrectly) called crystal glass, became hugely popular after its invention, especially in the Victorian era in the mid- to late-1800s. “Even aristocrats or wealthier people would be happy to wear glass paste jewelry,” says Walker. And jewelers began to really mess around with the possibilities of a beautiful, easily manipulated, and extremely inexpensive gem; they added colored lacquer to the settings to give the glass a color, or even inserted a bit of metallic foil underneath to increase their shine.

But fashions changed, and in the late 1800s, the claw setting became very popular.

The claw setting grips the gem while exposing as much of the gem’s body as possible, so you can get light flowing through the entire gem. Jewelers may have even pushed this style to fight back the wave of crystal glass, because at the time, crystal glass didn’t hold up to the scrutiny of that kind of full-through view. But the glass-makers responded, and the most important was Daniel Swarovski.

Bohemia, an area now part of the Czech Republic that borders Austria, has a very very long history of glass-making (and it remains one of the top three producers of silica in the world). Bohemians created lots of innovative techniques and processes for making glass; in the Renaissance, it was Bohemians who discovered that potash, potassium-heavy plant ashes soaked in water, when combined with chalk, could make for an easily workable and spectacularly clear glass, an innovation still used today. Bohemian glass was and still is widely known for its artistry and craft, and Daniel Swarovski’s father owned a glass-making factory. Young Swarovski was obsessed with glass, and in 1892 patented a new electric cutting machine, powered by hydroelectricity from the alpine waterfalls in the Austrian alps, for cutting glass.

In 1895 Swarovski founded the Swarovski company, originally called A. Kosman, Daniel Swartz & Co. (Swarovski changed his name due to rising anti-Semitism; as both a protective and marketing measure, it seems to have worked). The company’s factory was set up in the tiny town of Wattens, Austria, at the foothills of the Austrian Alps, to take advantage of the mountain’s hydroelectric possibilities.

What makes Swarovski’s crystals better than its competitors? It’s all about brilliance.

Swarovski Crystal Worlds park. (Photo: Costel Slincu/flickr)

The word “brilliance” is a shortcut to describing to the path light takes through an object, and how it appears to us during that process. “Brilliance refers to a property of glass that is related to two things scientists call the ‘refractive index’ and the “dispersion” of the glass,” says Cook. “The science here starts to get pretty complicated quickly, but the short of it relates to how much light is bent, or ‘refracted,’ when it passes through an object, and how much light of different colors are bent compared to each other or ‘dispersed.’”

Some gemstones are naturally very brilliant, meaning they have a high refractive index and high dispersion, “giving an illusion of the gem being larger than it actually is, and it becomes colored strongly as the light is broken into many rainbows,” says Cook. Diamonds are very brilliant. So is zirconia. And so are Swarovski crystals. The specific shape and the chemical makeup of Swarovski (which, again, they won’t share) combine to make them pretty spectacular. Though you’d be hard-put to find a jeweler who’d agree with you. “If you look closely, in the light, in particular, a well-cut diamond is always going to have more fire and more brilliance than a glass crystal,” says Walker. But that, really, is debatable, and also flexible: there’s only so much you can do to a diamond, but a synthetic material like Swarovski crystal has no limits. There’s no particular reason to assume that synthetic crystals won’t surpass diamonds in brilliance at some point.

Swarovski’s strength is two-fold. In sheer engineering muscle, the company is unmatched; its crystals aren’t just used for jewelry, but also for optics (binoculars, military stuff), abrasive tools, and intelligent, LED-based road lighting systems. But it became a household name thanks to its marketing and design department. In the mid-1950s, Swarovski worked with Elsa Schiaparelli to design custom-made Swarovski crystals for Schiaparelli’s jewelry. Chanel soon followed. Swarovski’s ability to create, basically, anything a designer wants, is unmatched in the fashion world; a jeweler can’t just make you a perfect cube of a sapphire, a neon orange sphere, or a dress made of a thousand rubies. But Swarovski can.

Rockefeller Center ornament. (Photo: karlnorling/flickr)

The company’s biggest new break came when they partnered with Alexander McQueen for his Spring/Summer 1999 collection. The collection is a perfect example of late 1990s/early 2000s prosperity run amok; it is a raucous, gaudy collection of thousands of sparkly perfect glass crystals, cubic headdresses, and exposed nipples. It brought Swarovski to the attention of Hollywood and New York: here were affordable, but wildly ostentatious gems that are somehow approved by the fashion cognoscenti. For the first time in centuries, it was cool to wear what is, in effect, costume jewelry.

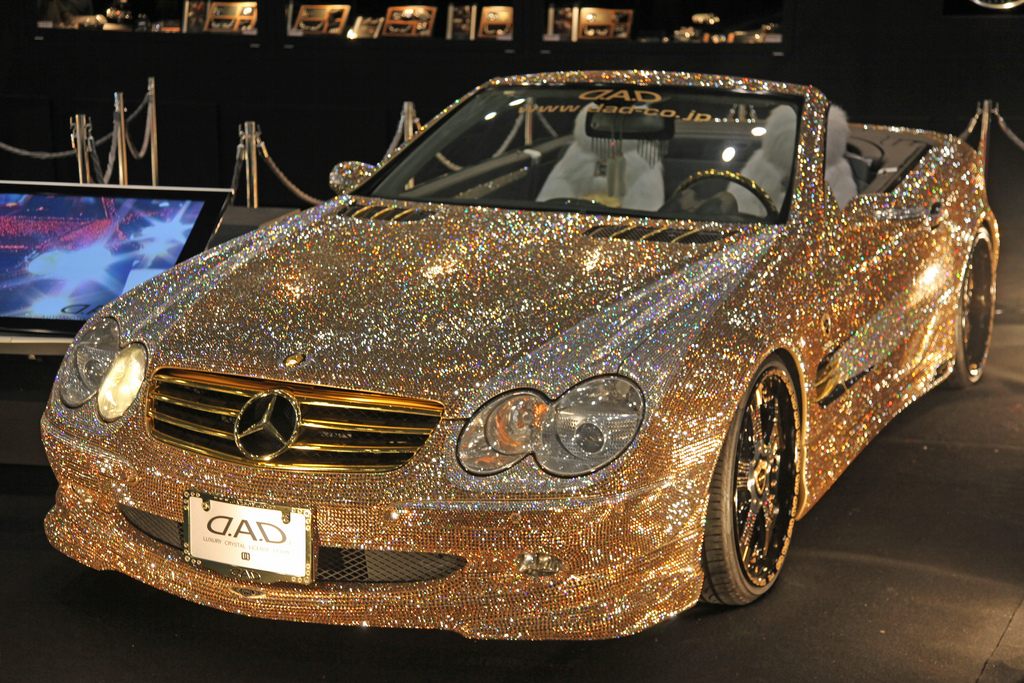

In 2009, speaking to Metro UK about her new pink Bentley convertible (estimated cost: $400,000), Paris Hilton said: “It has Swarovski crystals everywhere. It’s the Paris pink from my brand.” Paris Hilton and Swarovski crystals go together like Britney Spears and denim. Swarovski’s designs following the McQueen show in 1999 were very of the time: aggressive, outsized, luxuriously in-your-face. This was the era of the Swarovski-studded Motorola Razr cellphone. In 2006, the New York Times wrote, “For many people who had never given much thought to crystals, confusing the multifaceted beads with, say, sequins, ‘Swarovski’ is now inextricably tied to fashion.”

Swarovski Merc at Toyko Auto Salon. (Photo: Chris Brown/flickr.)

Every major designer—Chanel, Louboutin, Louis Vuitton, hell, Ray-Ban even got in the mix—could afford to jump in and do their own crystal riff. And Swarovski was happy to provide the crystals. A giant museum, the Swarovski Kristallwelten, was built in 1995 in Wattens, where the factory is. The Kristallwelten is still one of Austria’s biggest tourist attractions.

The company is less in the limelight than it was 15 years ago, but it’s still a thriving business; it makes the giant crystal that sits atop the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree every year, Rihanna wore a sheer dress covered in thousands of Swarovski crystals to a fashion awards show in 2014, and the company has an annual revenue of over $3.3 billion. Perhaps its strength is that while the ’90s Swarovski fashions look pretty awful by today’s standards, the company’s wares, even though they’re nothing more than bits of colored glass, remain very pretty. Glass is, by definition, malleable.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook