The Strangely Quiet Afterlife of a Brazilian Prison Town

The tropical beauty of Dois Rios comes with an ugly history.

The village of Dois Rios is home to one church, two restaurants, zero grocery stores, and about 90 residents living among dozens of buildings that are being swallowed by the tropical forest. It sits 100 miles west of Rio de Janeiro on the southern coast of a rugged, largely untouched island called Ilha Grande, where a small plain breaks the mountainous landscape.

Despite the lush, encroaching canopy, the buildings are not hard to find. They are scattered among the eerily empty streets—cars are banned in Ilha Grande, and Dois Rios can be so quiet you can hear your footsteps—that stretch between the foothills and the white sandy beach, where two rivers flow into the Atlantic Ocean, giving the village its name (Dois Rios means “Two Rivers” in Portuguese). Tropical vegetation has grown inside many abandoned houses, making the paint flake and the ceilings crumble. The forest has reclaimed the old soccer pitch, now an impenetrable grove. The old main square has turned into a meadow, and the old obelisk in its center sticks out of the tall grass.

Locals go about tranquil lives at this edge of the world. “It’s a very quiet place,” says Moises, a middle-aged street vendor who asked to be identified with his first name. “It’s good for the second part of your life.” Moises makes a living selling food and drinks to the tourists who visit Dois Rios’s beach. They usually arrive from Abraão—the only sizable village in Ilha Grande, on the north coast—taking a two-hour hike on a dirt road that serves as Dois Rios’s only land connection.

As he holds a metal cup from which he sips chimarrão—a hot, bitter infusion that is southern Brazil’s answer to Argentinian yerba mate—Moises concedes that young people wouldn’t find Dois Rios exciting. “There are no jobs, there is nothing to do,” he says. There is also no phone signal, and he uses a yellow two-way radio to reach his supplier.

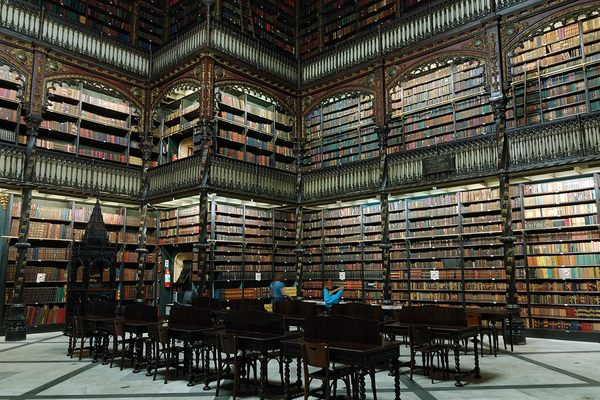

The reason why Dois Rios feels like a ghost town, but one that hasn’t quite died yet, lies in an imposing white building at the end of town, opposite the start of the dirt road to Abrãao. This place, which now houses a small museum, is what remains of one of Brazil’s most significant prisons, most recently known as the Instituto Penal Candido Mendes. Its walls keep Dois Rios’s darkest secrets.

Before 1884, most of present-day Dois Rios was covered by coffee and sugarcane fields where enslaved Africans were forced to work. More than four million enslaved people were taken to Brazil as part of the slave trade, and thousands were landed in Dois Rios and the rest of Ilha Grande. At one point, 5,000 enslaved people worked on one farm on the island, and slavery was widespread even among small landowners. In Dois Rios, many enslaved workers were diagnosed with fractures and illnesses connected to the brutal conditions.

It was against this backdrop, as Brazil prepared to abolish slavery in 1888, that authorities bought the land, and 10 years later decided it would be an ideal place for a prison.

“At the time, the concept of the prison island was very strong in the West,” says Gelsom Rozentino, an associate professor at Rio de Janeiro State University who runs the Dois Rios museum. Some of the world’s most famous prison islands were set up in the second half of the 19th century, including Alcatraz (which became a military prison in 1868), Devil’s Island (1852), and Pianosa (1858). Governments liked islands because they promised remoteness. Even today, getting from Dois Rios to Rio de Janeiro means embarking on a two-hour steep and muddy hike to Abraão, a one-hour ferry ride, and several hours on a bus. “It meant perfect isolation for the individuals that were considered dangerous for society,” Rozentino says.

Authorities built Dois Rios as a “prison town” where virtually every activity revolved around the prison and its hierarchy. Houses were assigned according to the officials’ pecking order, with the largest ones closer to the beach reserved for high-ranking officials. An austere order still governs the village today, and the streets follow a gridiron pattern. Even the palm trees and mangroves form meticulously straight lines.

Initially, the prison was planned as a “correctional colony”—a place where people with criminal convictions and political prisoners would be “scientifically” reformed through labor. In reality, it soon became a place of unspeakable suffering, especially in its early decades. Behind the 20-foot-high wall and the watchtowers, the incarcerated were treated as “subhuman,” says Rozentino. On one occasion, in 1955, a guard allegedly got away with hitting a prisoner with a machete, then shooting him in the foot three times as he ran for help.

“People don’t come here to correct themselves,” wrote Graciliano Ramos, an acclaimed author and leftist politician who was kept here in 1936. “They come here to die.”

Prisoners were often fed poorly, while forced labor, torture, and violence were rife. When word of prisoners’ conditions reached the continent, newspapers referred to the place as “a Ilha da Maldição”—the Isle of Damnation.

Over time, much of the life of the community outside the prison walls came to depend on prison labor. Incarcerated workers baked fresh bread for the whole island. They swept the streets, cleaned houses, grew vegetables, and collected the trash.

This is perhaps one of the reasons why Dois Rios became a village of paradox. Conditions in the prison could be hellish, but civilians remember the place as pleasant and well-run. “It was a great place to live,” says Shirleno Olivera, a private security supervisor in Rio de Janeiro who grew up in Dois Rios, where his father worked as a prison guard. “Everything was clean and looked after. Things worked.” To civilians, much of the suffering would have been invisible.

During World War Two, Dois Rios housed political prisoners whom Brazil perceived as dangerous. The conditions gradually improved, especially after the 1950s and 1960s. Some incarcerated people were even allowed to live outside the jail with their families, and built shacks at the edge of town. The children of prisoners “spent time with us, went to the local school, we played ball together,” Olivera says.

Over the years, many well-known prisoners did time in Dois Rios. Graciliano Ramos was jailed without a trial and wrote about his suffering in Memories From Incarceration. João Francisco dos Santos, the son of formerly enslaved parents who became a hustler, legendary capoeira street fighter, and flamboyant drag performer—hence his nickname, Madame Satã (Madam Satan)—remains an icon for the marginalized. After Dois Rios became a maximum-security prison in the 1960s and 1970s, Willians “the Professor” da Silva Lima, Paulo César Chaves, and Eucanã de Azevedo associated here in 1979. They set up what would become Brazil’s most notorious armed gang, the Comando Vermelho, which still controls large parts of Rio de Janeiro.

But eventually the deterioration of the building and the rise of prisoner’s organizations—which planned hunger strikes, protests, and riots—led the authorities to progressively abandon the prison. In 1994, much of the complex was demolished through a series of blasts. One former resident of the town described the detonations as a huge blow, as though “an atomic bomb exploded in my heart.”

For the community, conditions worsened. The bread supply, which depended on prison labor, was cut off. The school was discontinued. The cinema, workshops, and prisoners’ homes fell into disrepair. Because much of the island had become a state park, people could not use cars to move around. Life became tough. “Residents had to walk 10 kilometers [to Abraão] to buy groceries, and children did the same to go to school,” says Ede Quézia, a current resident and the daughter of the prison’s former head of security.

About half of Dois Rios’s population is thought to have left in the mid-1990s. The forest crept into town. A few years later, Rio de Janeiro State University threw the community a lifeline. It set up a research center on the island and turned what remained of the prison into a museum, providing the community with jobs. (Quézia also works here.) It looks after the streets and runs a twice-daily shuttle to the nearest school in Abraão.

The university’s intervention, together with the state park restrictions, seems to have frozen time there, creating a new kind of paradox. It has stopped the deterioration of the town, and allows its residents to carry on with the quiet lives they like. It also staves off development. Tourism is growing across Ilha Grande: Abraão has seen a boom in visitors and has become a pricey, coveted holiday resort. But the windfall hasn’t reached Dois Rios. Original businesses are allowed to stay open, but new restaurants, hostels, or pousadas—family-run inns that are typical in Brazil and Portugal—are not allowed. “There is nothing that can be bought or sold,” says Rozentino, the university professor. Almost all of the locals are either museum and university workers or retired prison officials who enjoy the quiet. Quézia says there is little community to speak of. “People are not really for getting together,” she says. “It only happens when we’re invited to some museum or university event, and even then only a few people go.”

She says she likes life among the dazzling beaches and the pristine waterfalls, but it can be difficult. For example, the university employs a nurse, but if someone falls sick, they must make their way to Abrãao or to the closest hospital in Angra dos Reis, on the continent.

Shirleno Olivera, the Rio de Janeiro security supervisor who grew up here, says he feels a deep sadness whenever he visits. “It’s very sad to arrive and see it in this state,” he says. He believes that people who see it today, lured by the surrounding nature, can understand little of what Dois Rios was—“what it really was,” he says.

They only see a sleepy, eerie village that the forest is starting to reclaim—a place that is no longer heaven, and no longer hell.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook