The Painstaking Process Behind Those Wild WWI Naval Paint Jobs

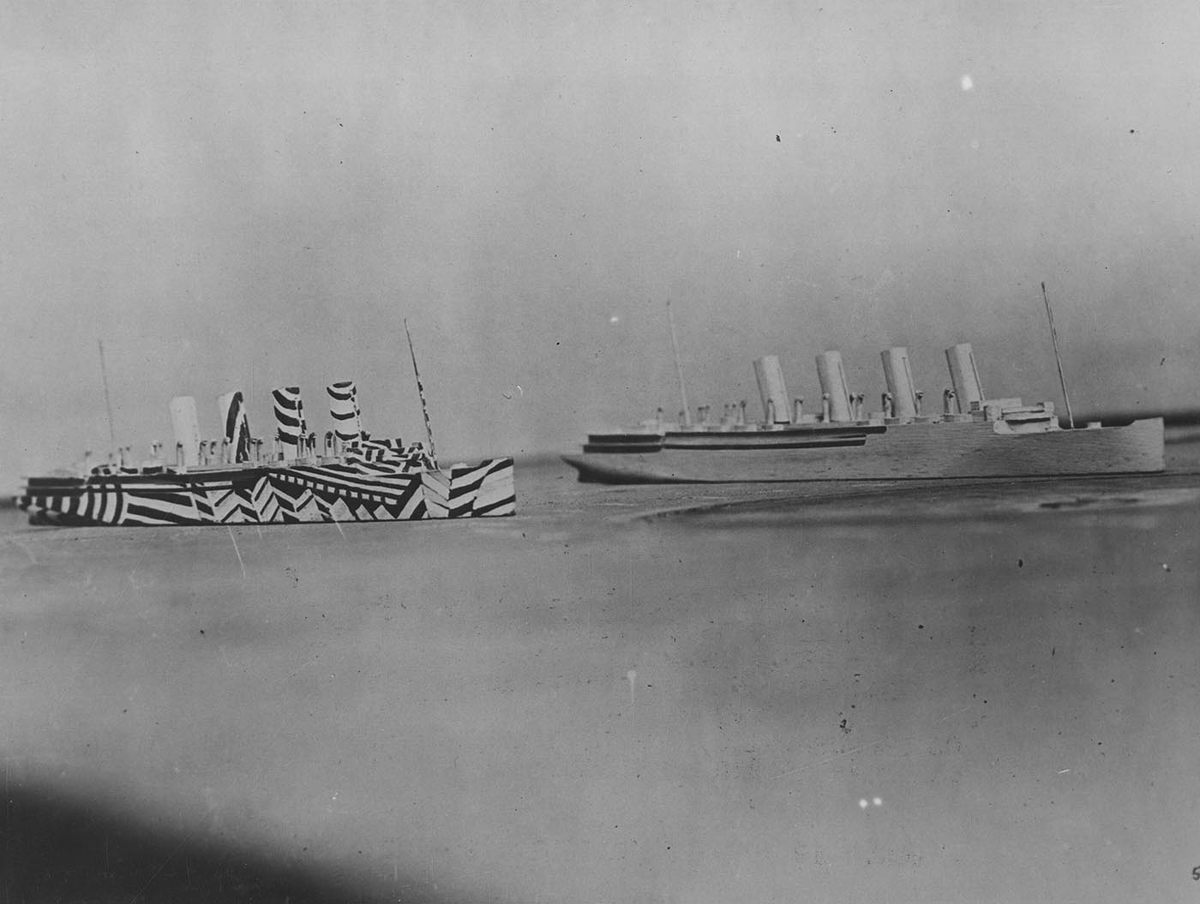

“Dazzle” paint was first tested on tiny model ships.

There were plenty of new, sometimes bizarre opportunities for camouflage in World War I: searchlights disguised as shrubbery, lookouts concealed as trees, and the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps dressed in suits that blended seamlessly into the landscape. But at sea, the U.S. Navy required a different type of visual trickery: what came to be known as “dazzle” paint.

The idea was for ships to be seen, “but seen incorrectly,” explains Jennifer Marland, Curator of the National Museum of the United States Navy. If paint could be used to distort a ship’s angles, the thinking went, that would “make it difficult for the ship to be targeted efficiently by a submarine.”

German submarines posed a devastating threat to the Allies. After a hiatus in unrestricted attacks following the sinking of the RMS Lusitania, the German Navy recommenced open U-boat warfare in February 1917. In the second half of April of that year alone, an average of 13 ships were sunk per day. It was around this time that the British artist and Royal Navy volunteer Norman Wilkinson had the idea for dazzle paint.

“Strong, distracting lines would mask the bow, stern, and sections that might be used to estimate the range, speed, or course of the ship,” says Marland. “Submarines only had a few moments at periscope depth to fire their torpedo before they risked being seen. The aim was to make the estimation of where the ship would be so difficult that the torpedo would not be fired, or would be fired and miss.”

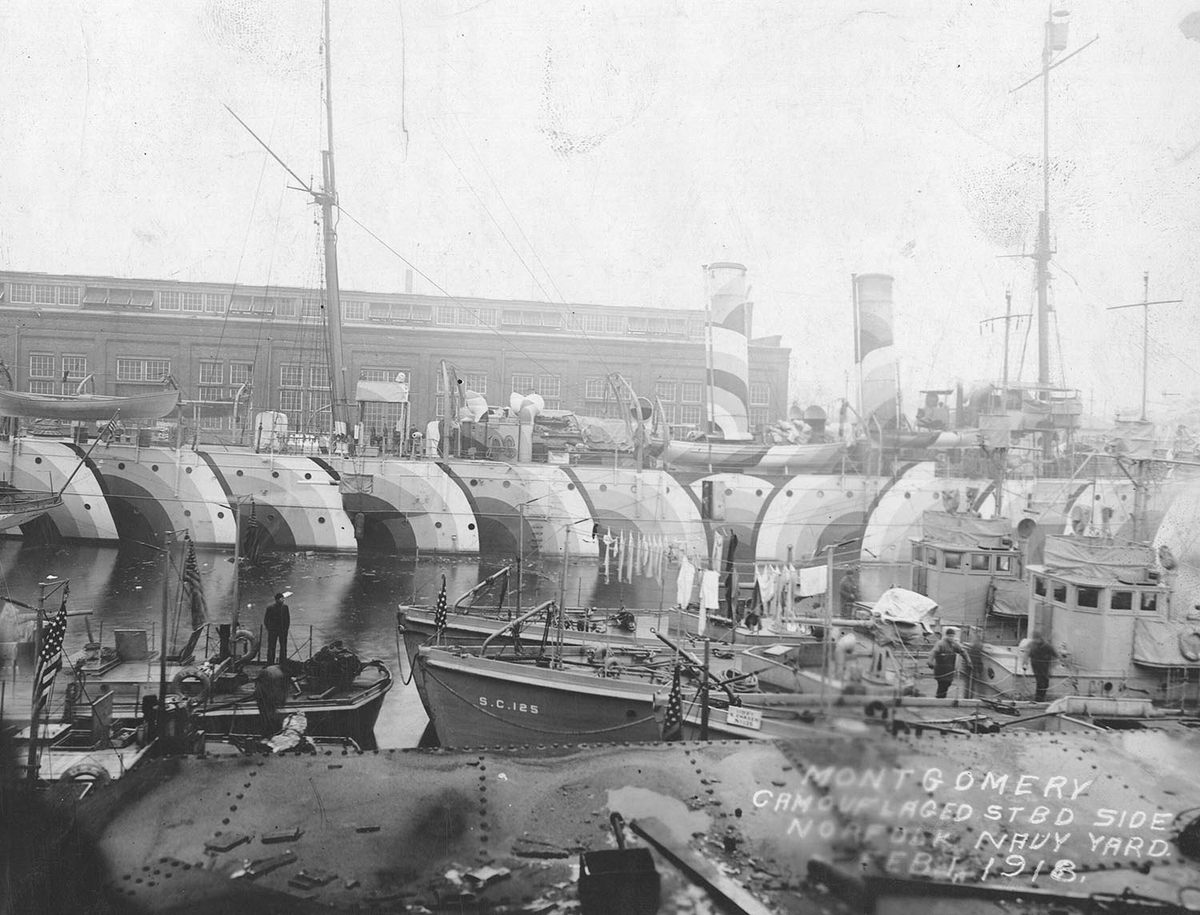

These distracting lines might include patterns on the smokestacks to obscure what direction they were facing, or curved shapes along the hull to create the impression of a bow wave. “The idea was that no design would be completely reused,” explains Marland. “Each side of the ship was different, but the aim was to obscure vulnerable parts of the ship so that there would be similar ideas of what to obscure by class.”

Before these patterns could be applied, they needed to be designed and—crucially—tested. Lieutenant Harold Van Buskirk was in charge of the U.S. Navy’s adoption of the British dazzle paint system. After receiving the blueprints of a ship, the Camouflage Section constructed a wooden scale model. The model was then tested using a turntable, a periscope, and a mirror to mimic the correct conditions.

“The tests replicated the view of the ship through a submarine periscope,” says Marland. “The tester had to estimate the range, speed, and course of the model ship and then fire a simulated torpedo. If he misses the model, the paint design is a good one.” Once approved, the Emergency Fleet Corporation of the Shipping Board applied the design onto the ships, under strict instructions not to depart from the color or pattern scheme.

In 1919, Van Buskirk calculated that torpedoes sank less than one percent of dazzle-painted vessels. However, there were other factors to consider. “Dazzle was adopted in Britain around the same time as convoys were also adopted,”explains Marland, “leaving the advantages of one protective measure over the other difficult to fully analyze.”

The lengthy process by which designs were tested on model ships is documented in a collection of photos now held by the U.S. National Archives. These records show the artists of the Camouflage Section—which included Everett Warner—carefully applying paint to wooden models, rooms full of tiny painted ships, and their real-life counterparts covered in geometric patterns. The one thing these black and white photo don’t reveal, however, are the colors of the dazzle paints, which took on a range of contrasting hues.

The National Archives started digitizing this collection about four years ago; the last batch went online in 2017 (one of the many amazing collections made available on the internet that year). AO has unearthed this selection of dazzle-paint archival images.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook