How a Massive Fatberg Went From Sewer to Science Museum

The underground menace is now a reminder that people should be kinder to their pipes.

Tracie Baker wasn’t sure what tools she would need for the dissection. Baker, an environmental toxicologist at Wayne State University in Detroit, studies the presence and effects of toxins and endocrine-disrupting compounds in water. She’d cut up fish before, but never anything quite like the tangled mess of fats, oils, grease, and trash that had arrived in her lab. It was two 10-pound chunks of fatberg, taken from a massive sewer-clogging bolus. Baker figured she’d need gloves, probably the thick rubber kind people use for washing dishes, and elbow-length seemed safest. Beyond that, she says, “We weren’t exactly sure what was going to work.”

Baker and her colleagues were trying to learn as much as they could about the fatberg, which had been hauled from a sewer in Clinton Township, a suburban Michigan community about 25 miles northeast of Detroit in Macomb County, while it was still fetid and fairly fresh. When they were done, it would be enshrined in a new exhibit at the Michigan Science Center.

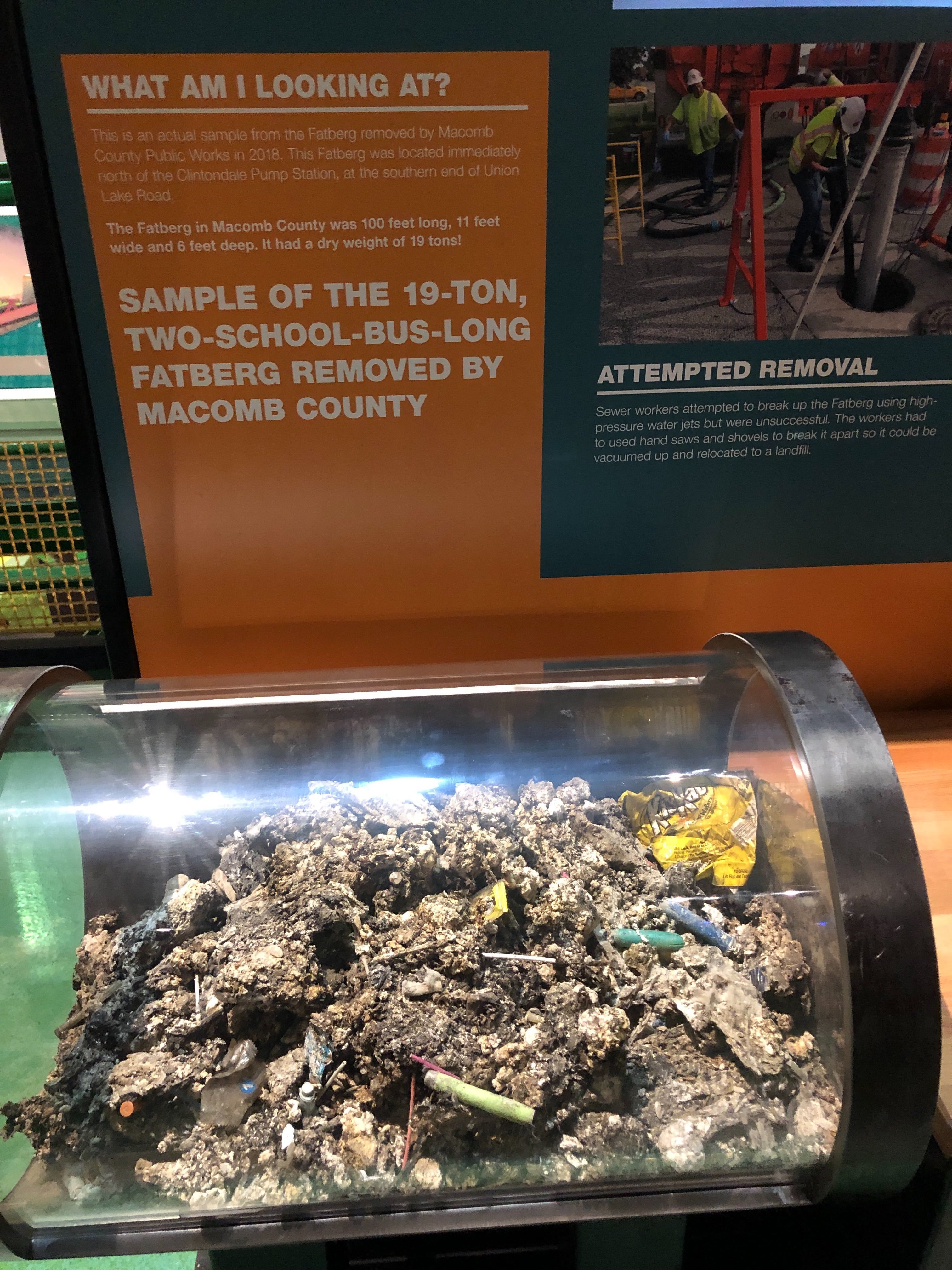

Crews from Macomb County Public Works encountered the fatberg during a routine survey. The situation wasn’t critical, but officials knew it needed to come out, says Dan Heaton, the office’s communications manager. Fatbergs are always unwelcome guests, and this one had really made itself at home. The 50-year-old sewer pipes are about 11 feet in diameter, and the fatberg was almost exactly as wide, six feet deep, and a startling 100 feet in length—same as two school buses. Its 19-ton bulk occluded the sewage pipe enough that officials worried it would mean a backup of hydrogen sulfide—“sewer gas”—that could corrode the pipes’ cement interiors.

It’s dangerous to send humans down into narrow, dark, gas-filled sewers, so crews generally enlist high-powered water jets first. These can be enough to get things flowing again—but they didn’t do much against the Macomb County monster. The public works team dispatched crews down into the belly of the system to attack it with hacksaws and axes. Little by little, the crew carved up the material and fed it into a wet-vac truck at street level. Extraction wrapped in September 2018, and in the light of day, Heaton says, the sopping slurry looked like an exceptionally unappetizing and “very thick stew.” The liquid portion of the blockage was sent on its “merry way to the treatment plant,” Heaton says, while the solids traveled to a storage area. A sample was calved for Wayne State researchers, and ultimately, traveled to the Science Center.

Pieces of the fatberg were worth keeping around for analysis because “so few fatbergs have been characterized,” Baker says. With the exception of a handful extracted in London, studied with gas chromatography or forensically prodded in front of television cameras, the usual approach to them is, “Let’s get this out of here, throw it in the trash, and move on,” Baker says. Along with her Wayne State colleague Carol Miller, a civil and environmental engineer, Baker applied for National Science Foundation funding to take a closer look at the Macomb County fatberg. The team wanted to know exactly what the mess was made of and how it might affect the ecosystem both inside and outside of the sewer.

But there was a bit of a delay—a few months between the time public works extracted the fatberg and when the researchers got to work. During that period, the festering thing was placed in two 10-gallon aquariums, wrapped in garbage bags. Baker and Miller had wanted something they could see through, and someone from public works had a couple handy at home, Miller recalls. But the tanks had a problem: They made for an inescapably humid environment. When the researchers received the tanks in the lab, the chunks looked like “gooey blobs,” Baker says—midnight black and wriggling with worms and larvae. The smell was overwhelming. When the researchers first opened the tanks, “We were in a small room,” she adds, “and everyone’s eyes were watering.” The team hurried the samples to a fume hood and let them dry out for a few weeks at room temperature.

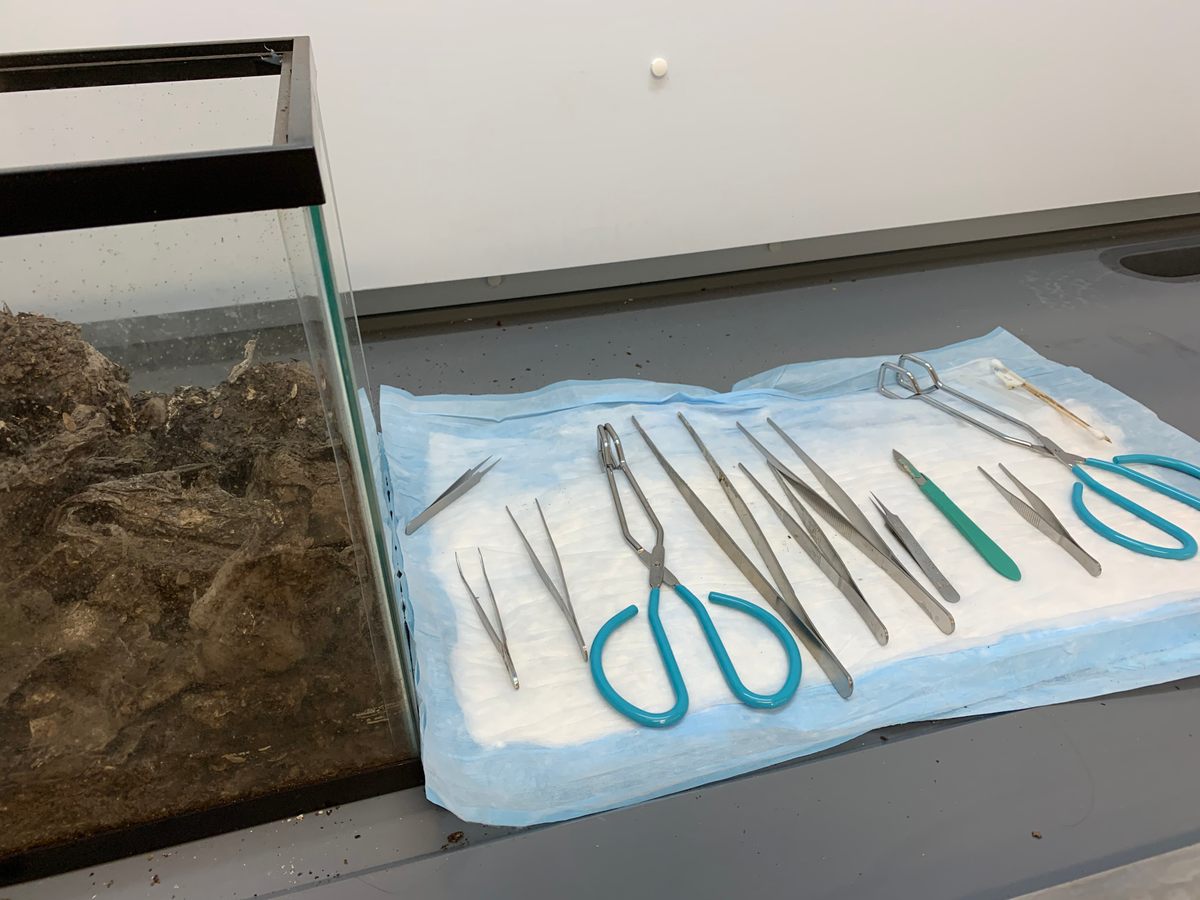

Once the fatberg was dry and as approachable as one could hope for, the team used a veterinarian’s X-ray equipment to peer inside so they could see if there was anything sharp in there. “We obviously didn’t want to get poked by something metal that had been in the sewer,” Baker says. She then reached for tweezers, scalpels, tongs, and scissors. One aspect of the project involved disarticulating the trash matrix to see exactly what had gotten trapped in it. Baker found plenty of wet wipes—the kind often cavalierly labeled as “flushable”—as well as tampon applicators, lollipop sticks, plastic coffee stirrers, and cigarette butts, plus a mustard packet, Kit Kat wrapper, syringe, and pen cap.

The researchers also assessed the composition of raw sewage, fats, and oils throughout the sample, as well as the microbial menagerie living it up inside. They found oleic acid, commonly found in cooking oil, as well as some bacteria that isn’t typically seen in sewers or feces, Baker says. They’re hoping to take a closer look at those interlopers later. The research “confirmed some things that we intuitively knew,” Miller says, especially that “much of the problem associated with fatbergs is really human-created.”

Next time around, if there is one, Miller wants samples from different parts of a fatberg, such as along the pipe wall and in the fleshy middle, and from the upstream and downstream ends. And Baker would want to brave the stench and dig through a still-wet sample to see how bacteria get along in the fresh oils and greases.

The fatberg chunks spent several months stinking up Baker’s lab. By the time they’d finished the dissection on the one piece—some of which they’ve held on to for future study—the other one was nice and dry, too. The researchers sealed it up in a box for its journey to the Science Center, where it has been on view since December 2019. Inspired in part by the Museum of London’s 2018 fatberg display, it is equal parts educational, titillating, and icky. Miller, Baker, and other collaborators contributed to the exhibit’s informative graphics and text about how ecologically troublesome fatbergs can be and how much they cost to remove ($100,000 in this case). And there is a simple request: Please, please, please, stop flushing trash down the toilet.

The segment on display is sealed in a cylindrical tube that looks like a sewer pipe, but clear, revealing the array of white and soot-gray gunk and the sprinkling of colorful trash inside. It looks a little like the jumbled contents of a vacuum-cleaner bag, or an oversized owl pellet.

As the exhibition evolves, Miller says, the organizers plan to add a game that some students at Lawrence Technological University* have devised. Players will be tasked with tidying up a messy apartment by deciding what goes in the trash and what can be flushed or washed down the drain. Players will also be able sift through a digital fatberg with a little “laser” to see where they went wrong, and where the trash wound up. The idea is to demonstrate, with a little scatological silliness, that if bad or uninformed choices can feed a fatberg, good ones can starve it.

In a way, the whole episode has turned Macomb County’s Clintondale Pumping Station into a fatberg field station. By examining the trash that’s intercepted there, the scientists are checking to see if the exhibit and other awareness campaigns are paying off in changing behaviors. They’re also examining patterns in where fats and wipes accumulate. Do they cluster near known restaurant corridors? Do wipes mound up near areas with a lot of little kids or elderly people, who may use many of the pre-moistened scraps? “We’re still doing a lot of sampling,” Miller says.

Meanwhile, Heaton says, the county will pilot a fatberg prevention project that’s a little like an IV drip of a substance similar to dish soap. The idea is that it could help prevent fat and grease from building up in the first place. “As interesting as a fatberg is,” says Heaton, “the goal is to never have another one.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that game was designed by students at Wayne State. It was designed by students at Lawrence Technological University.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook