A Newly Digitized Menu Collection Shows Off America’s Lost Railroad Cuisine

Once, Americans rode the rails for charbroiled steak, golden French toast, and prunes.

Ira Silverman was always on the go. In the late 1960s, the train enthusiast enrolled in Northwestern University’s Transportation Center in Evanston, near the great national rail hub of Chicago. This proximity gave young Silverman and his classmates opportunities for research, adventure, and unparalleled feasting.

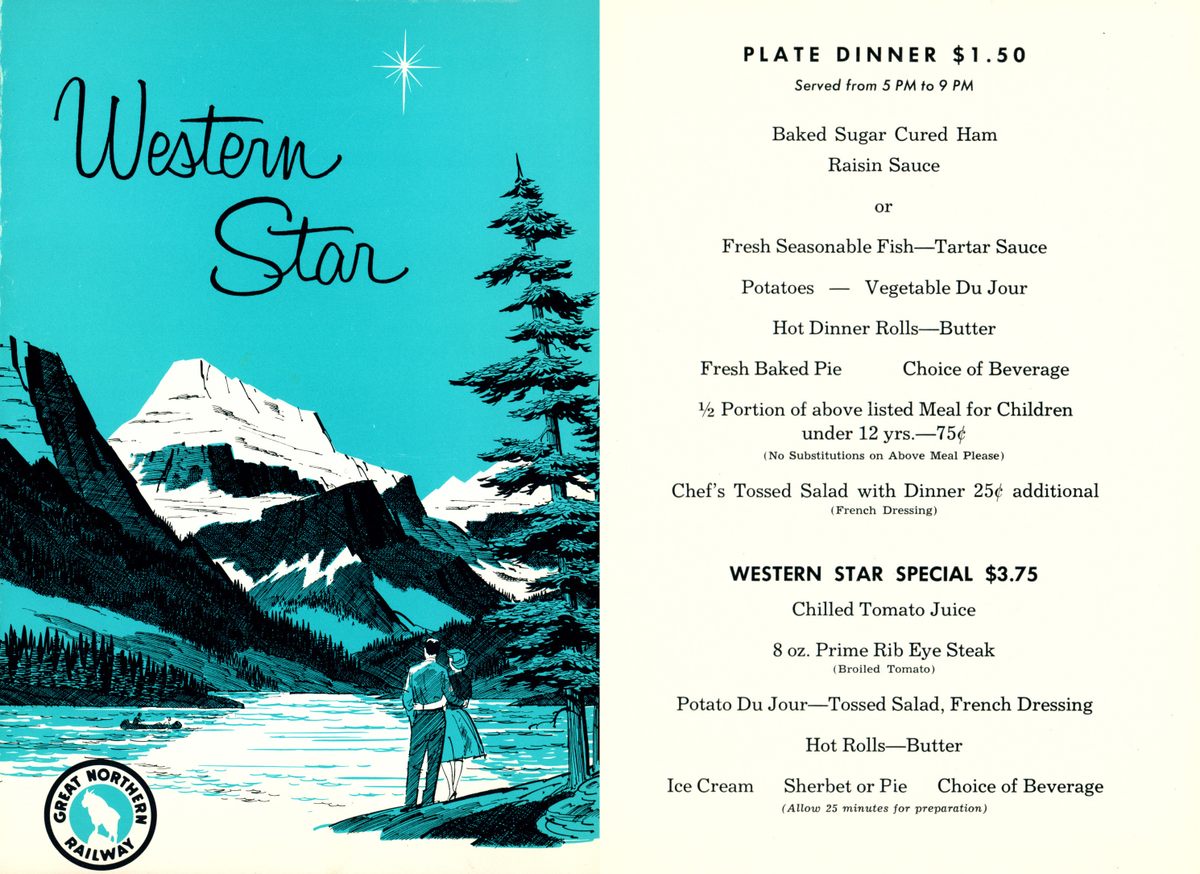

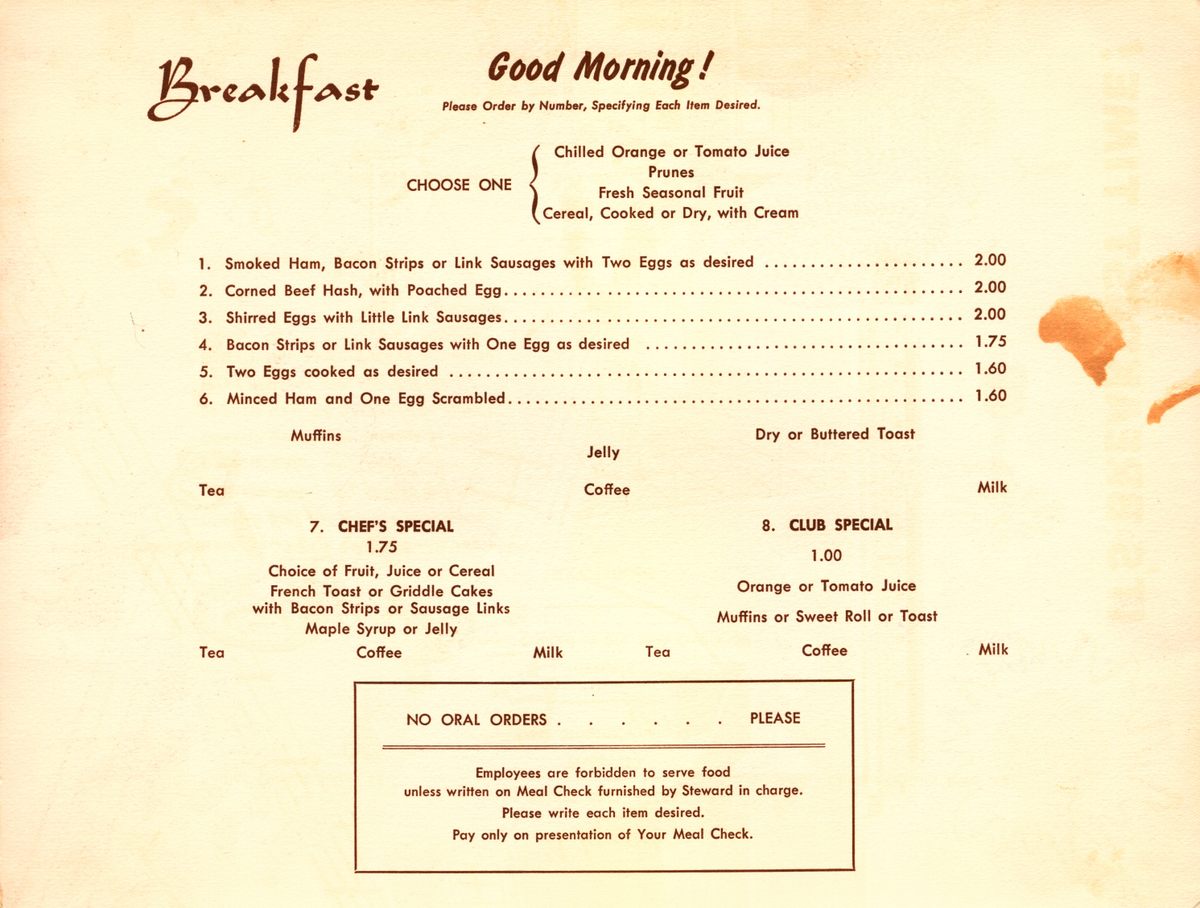

As graduate students in railroad transport, they regularly hopped on privately operated railroads that carried them to distant cities. But they always made sure to catch the evening return train, so that they could relish meals in a dining car while watching the shifting American landscape. With standard fare such as charbroiled steak, lamb chops, and fresh filet of sole, the experience probably far surpassed eating on campus.

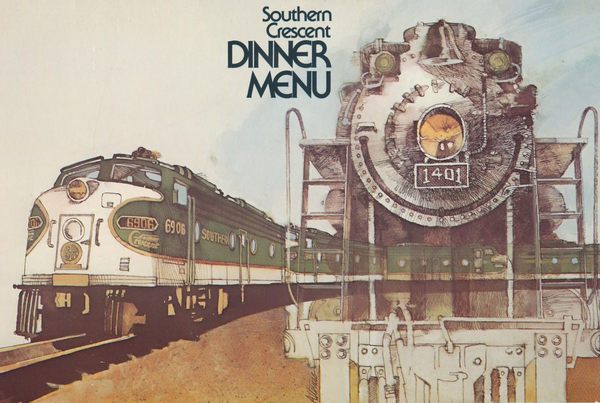

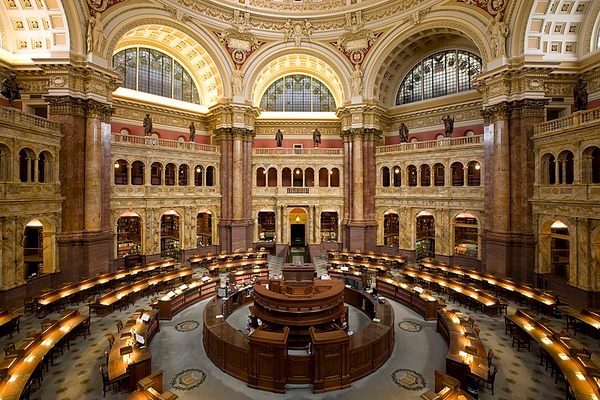

Silverman, now 73, clearly cherished these memories. He began collecting dining car menus, eventually amassing an archive of 238 menus and related pamphlets. After a long career in transit, he donated the collection to his alma mater’s Transportation Library, which recently digitized it in its entirety. The pages (almost all, impressively, unstained) offer a mouthwatering journey down the rabbit hole of deluxe railroad dining, when well-heeled travelers expected to sit at tables draped in white linen and indulge in outstanding meals plated on china.

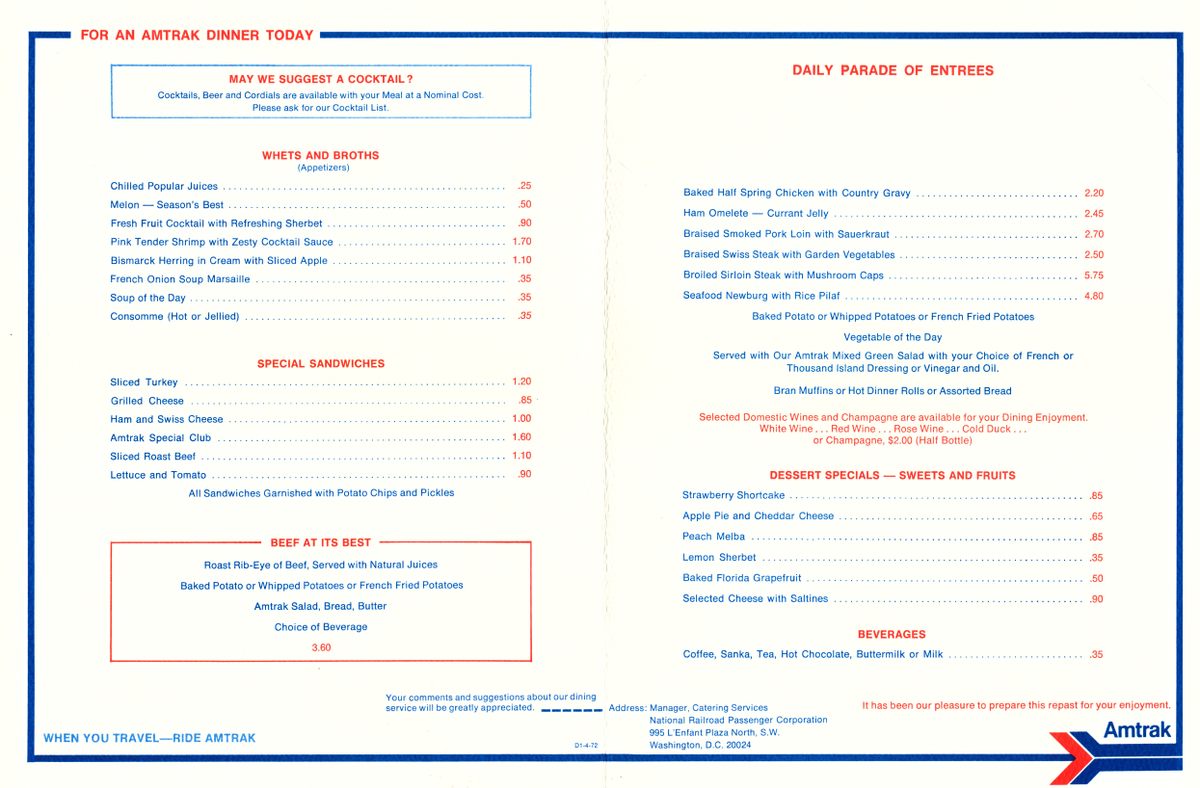

With Amtrak’s announcement that it is gradually eliminating the traditional dining car on its routes as a cost-saving measure, that experience—already simplified over the decades—might become a thing of the past. It’s part of a long slide that’s seen dining cars say farewell to fresh French toast, a perennial train favorite across the country, and hello to prepackaged chicken fettuccini.

“The mid-20th century seems to have been a golden age of railroad dining,” says Rachel Cole, Northwestern University’s Transportation Librarian. “It was never something that railroads profited on, but they used it to compete against each other and attract passengers. They took a lot of pride in offering selections that would be rivaled in restaurants.”

Some railroads would entice riders to the dining car with signature dishes. The Northern Pacific advertised its Great Baked Potato, a monstrous spud that could weigh anywhere between two to five pounds. It was served with a Northern Pacific-branded spoon and an appropriately sized butter pat. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad offered a popular “Help Yourself” salad, drizzled with Catalina dressing and blue cheese that a server would lug around in a huge bowl at dinner. Aboard a Gulf, Mobile & Ohio train, passengers seeking extra extravagance could order a special chicken sandwich embellished with hard-boiled egg, Thousand Island dressing, and caviar. The curious combo cost $2.25, or about $18.40 in today’s dollars.

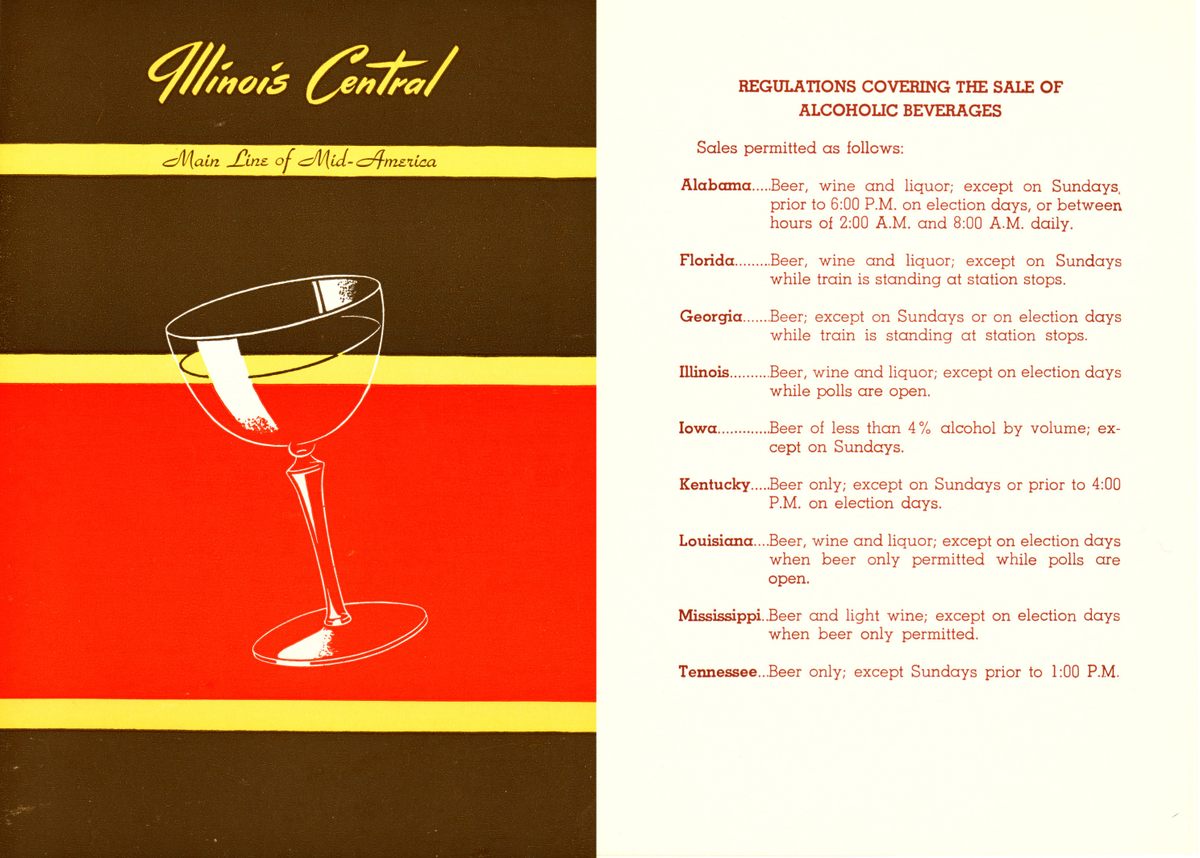

Then there were the drinks. Libations ranged from a classic martini to a Rob Roy to a complimentary bottle of rosé with dinner on the Penn Central. The Southern Pacific hosted a “Cocktail Time” with free hors d’oeuvres (plus a “Coffee Hour” in its lounge) which it plugged as “an excellent opportunity to get together for an enjoyable interlude.” A New York, New Haven, and Hartford menu teased: “For a real appetizer, enjoy antique bourbon on the rocks.” To accompany their chosen booze, adults could also purchase cigarettes, cigars, and playing cards. Unsurprisingly, aspirin and Alka-Seltzer were often included on the bill of fare.

The Ira Silverman Railroad Menu Collection is particularly rich in menus from 1960 to 1971, the final decade of privately operated long-distance train travel in America. By then, people had been devouring freshly prepped meals aboard trains for nearly a century. It all started in 1868, when George Pullman’s Palace Car Company introduced a railroad car with a small kitchen and two dining areas. (Almost exclusively, Pullman employed formerly enslaved African-Americans as porters and dining car waiters. They were paid poorly and endured blatant racism on a regular basis.) Railroad dining reached its pinnacle in 1930, as author James D. Porterfield notes in Dining by Rail: The History and Recipes of America’s Golden Age of Railroad Cuisine. That year, 1,732 dining cars were registered with the Interstate Commerce Commission, a former government agency that regulated the services of transportation carriers.

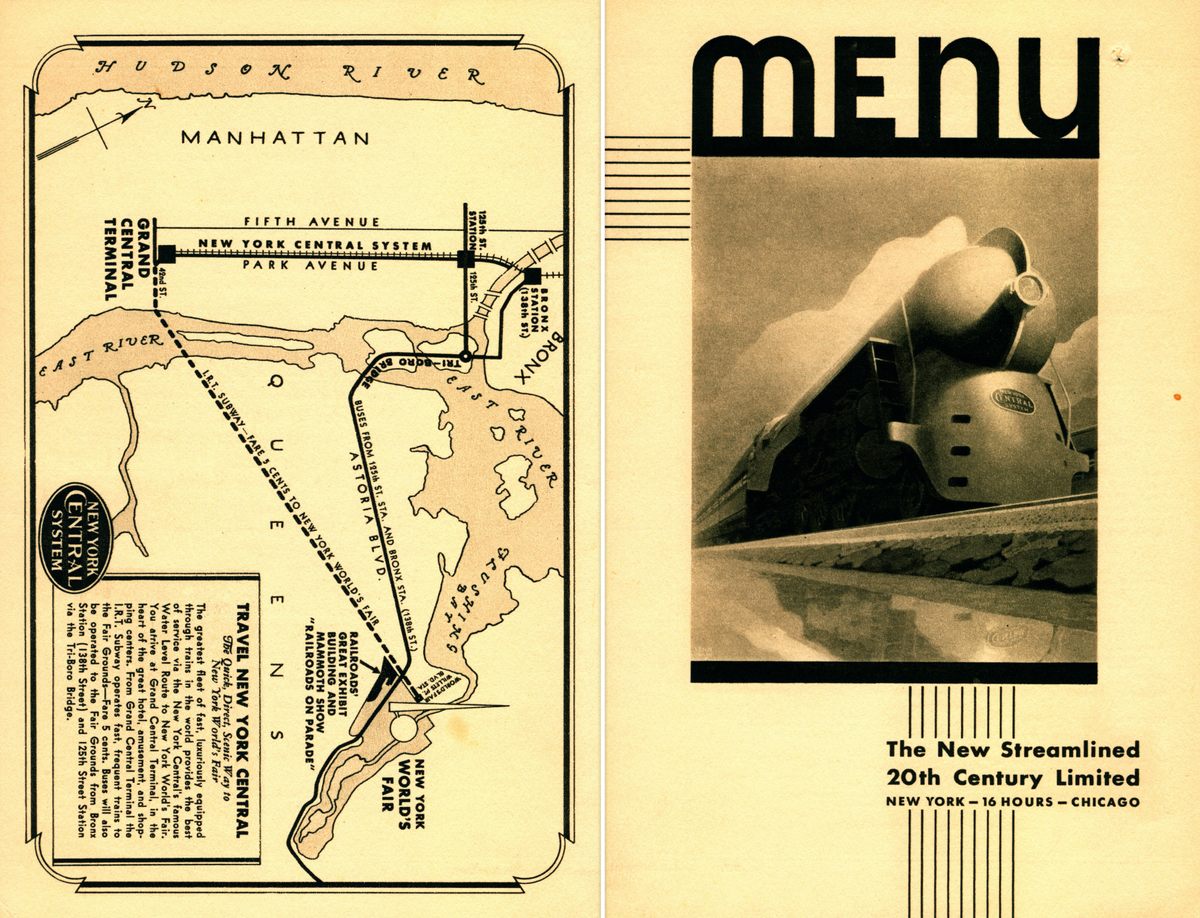

The earliest menu Silverman acquired was once perused by passengers aboard the famed 20th Century Limited train, which traveled between New York City and Chicago. It dates to 1939, one year after luxury Art Deco cars by industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss were added to the route. The train, majestic and futuristic, adorns the menu’s front cover; the back features a map illustrating connections from Grand Central Terminal to the World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows. Inside, an array of classy options speaks to an exemplary railroad dining service. Diners could opt for an opulent six-course dinner featuring English loin chop with kidney and fresh mushrooms, or exercise more freedom with the à la carte menu, which boasted genuine Russian caviar on toast and grilled French sardines. (Cary Grant, playing an adman in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, orders a brook trout with his Gibson on the 20th Century Limited.)

“You come across four- or five-course dinners pretty often,” Cole says. “Jellied, mid-century things also come up very often.” Among the smaller plates on the 1939 menu, for instance, are a cup of jellied consommé and jellied tomato madrilene—a cold tomato-based soup.

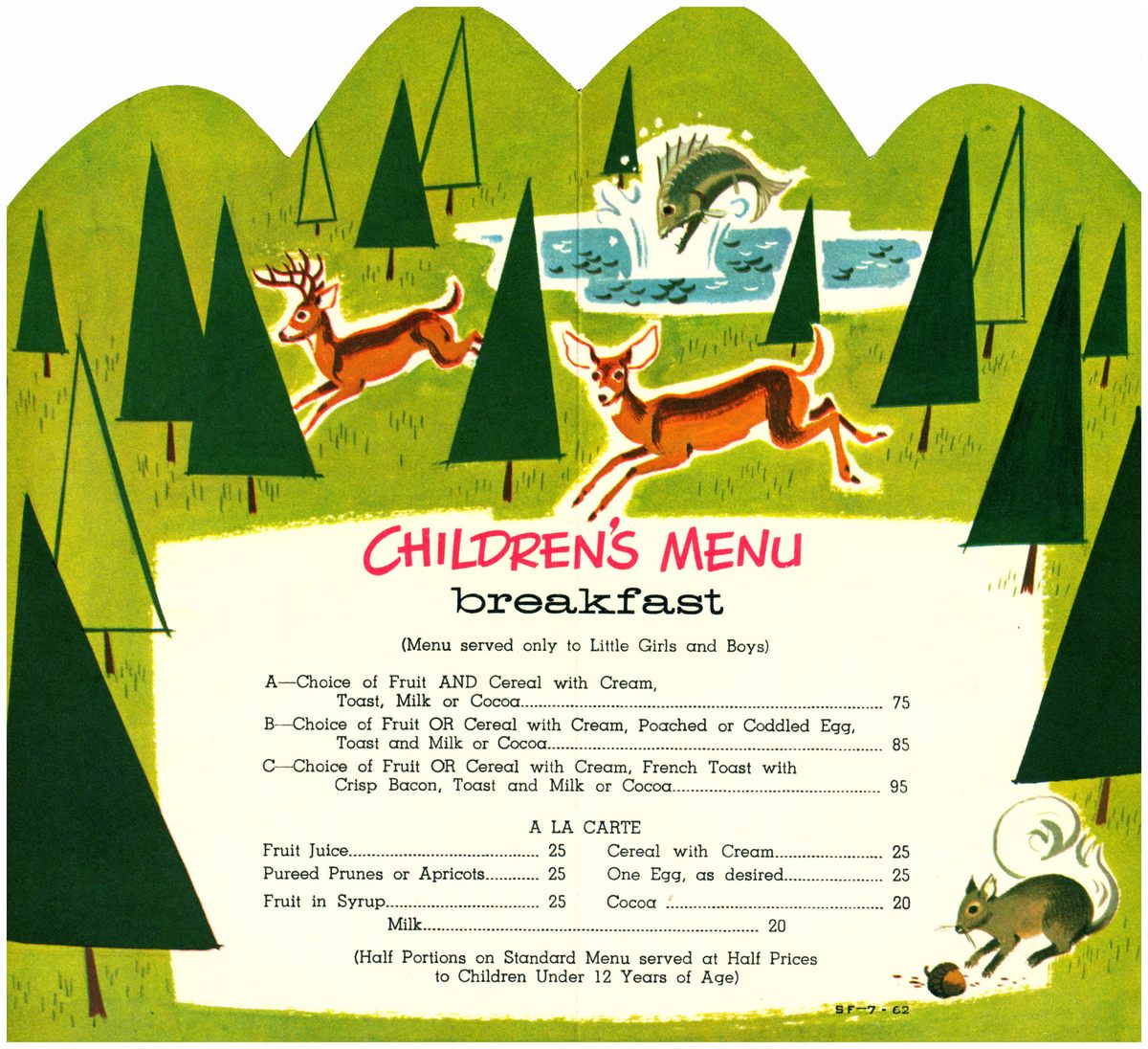

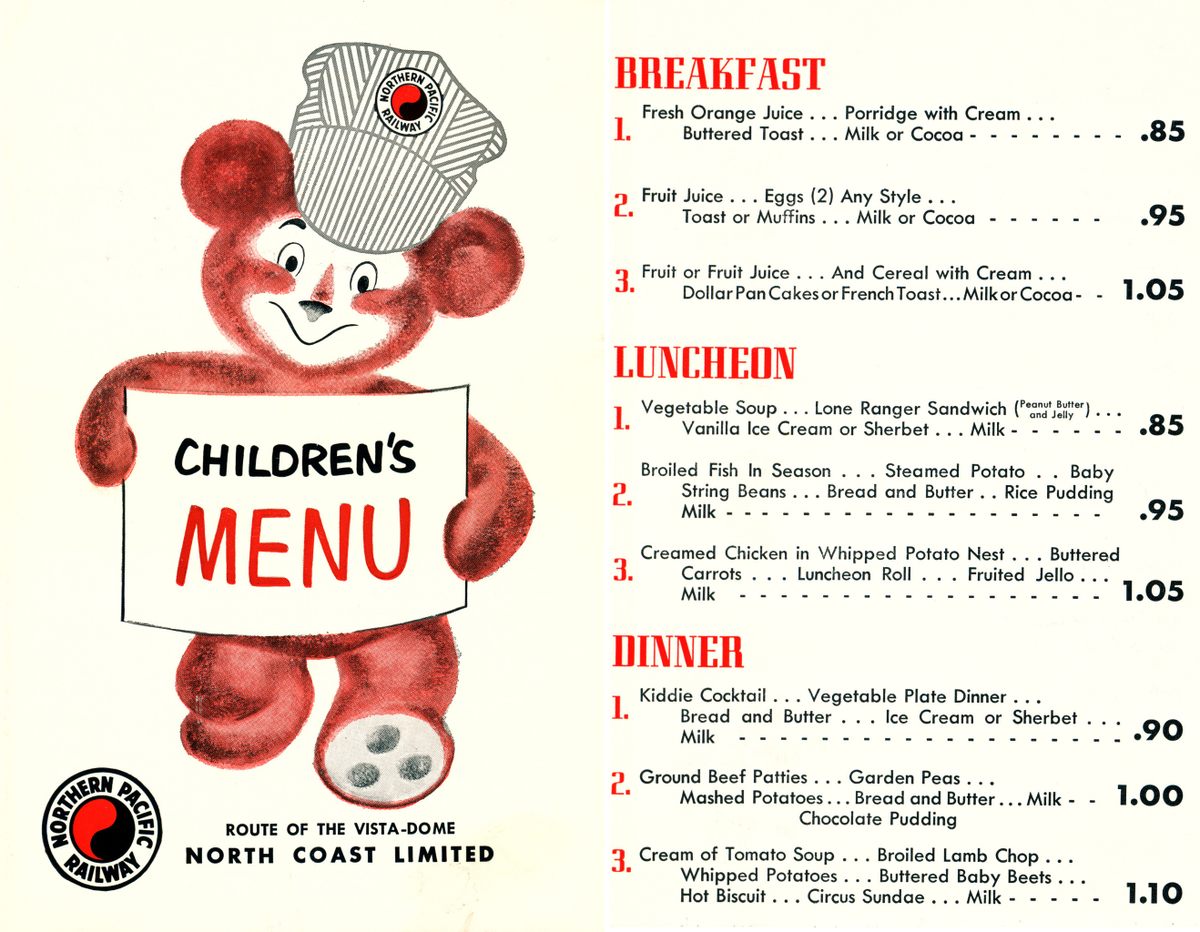

Many common railroad dishes would be considered offbeat to the 21st-century Amtrak rider. Long gone are the days when Welsh rarebit (fancy cheese on toast), kippered herring with eggs, and preserved figs were de rigueur. Plus, prunes often popped up, prepped in myriad ways: juiced, steamed, stewed with cream, cooked in syrup, and, for kids aboard the Union Pacific, puréed. Minors on that fleet would perhaps have preferred to slurp down a milkshake—available in chocolate, strawberry, or pineapple—or save room for freshly baked pie.

As Cole notes, “Children’s dining experiences were more sophisticated than we might imagine today.” She points out that menus for those age 12 and under offered much more than peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, instead featuring items such as grilled lamb chops, roast beef, and seasonal fish.

Gene Arenson, a self-described “lifelong railroad fan and advocate,” still remembers the first dining car meal he had, when he was a high school student. “It was a nice steak dinner with a baked potato and dessert, on the San Francisco Zephyr from Chicago to San Francisco in 1974,” he says. “In fact, I remember the server. His name was Ernie—quite a colorful guy. He took excellent service. But to be able to look out the window while you’re eating … you can’t describe it.”

This past August, Arenson launched a Change.org petition urging Amtrak and Congress to keep traditional dining car service on all long-distance trains. The railroad service, which on October 1 began cutting the amenity from long-distance routes east of the Mississippi River, replaced it with a “flexible dining menu” with ready-to-serve meals for sleeper car customers. The change, according to Amtrak, will save the company $2 million annually. Plus, as its executives have argued, millennials apparently aren’t comfortable with the idea of sharing tables with strangers.

“To me, that’s just malarkey,” Arenson says. “I’ve spoken to other people, and they’ve all agreed that that’s not an issue.” The new meals, he adds, are “glorified TV dinners. They look sloppy, never appetizing, and loaded with fat and sodium. Meanwhile, coach passengers are now at the mercy of the café car, which is a glorified 7-Eleven.”

Many railroad advocates, he adds, fear that the cuts will eventually roll over onto the West Coast trains, too. Arenson has since been working with congressional representatives and the National Association of Railroad Passengers to call on Amtrak to rethink its strategy. “People are expecting to get what they pay for,” he says. With him are 146,647 signatories so far, many of whom have left comments describing the timeless romance of the dining car that draws them to train travel.

As for Amtrak’s claim that millennials are killing the dining car, Cole adds that it’s worth remembering that Silverman started collecting menus when he was a young person. “He took train rides just to enjoy the dining car experience,” she says. “I think that continues today. There are a lot of young people who enjoy that experience as much as he did.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook