The Long Ethical Arc of Displaying Human Remains

A look at why museums exhibit Egyptian mummies, but not Native American bones.

The woman lies in a coffin of cracked wood and faded paint. The casket lid, set above the body, features a carved face, beautiful and serene, with lips slightly curled up towards a wry smile. Her dried corpse is tightly wrapped in strips of brown linen with slits left open for her eyes, nostrils, and mouth. When she died 3,000 years ago in Egypt, the woman’s kin no doubt hoped the body’s preservation in a tomb would ensure her soul’s eternal afterlife. Instead, she rests behind a glass case at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

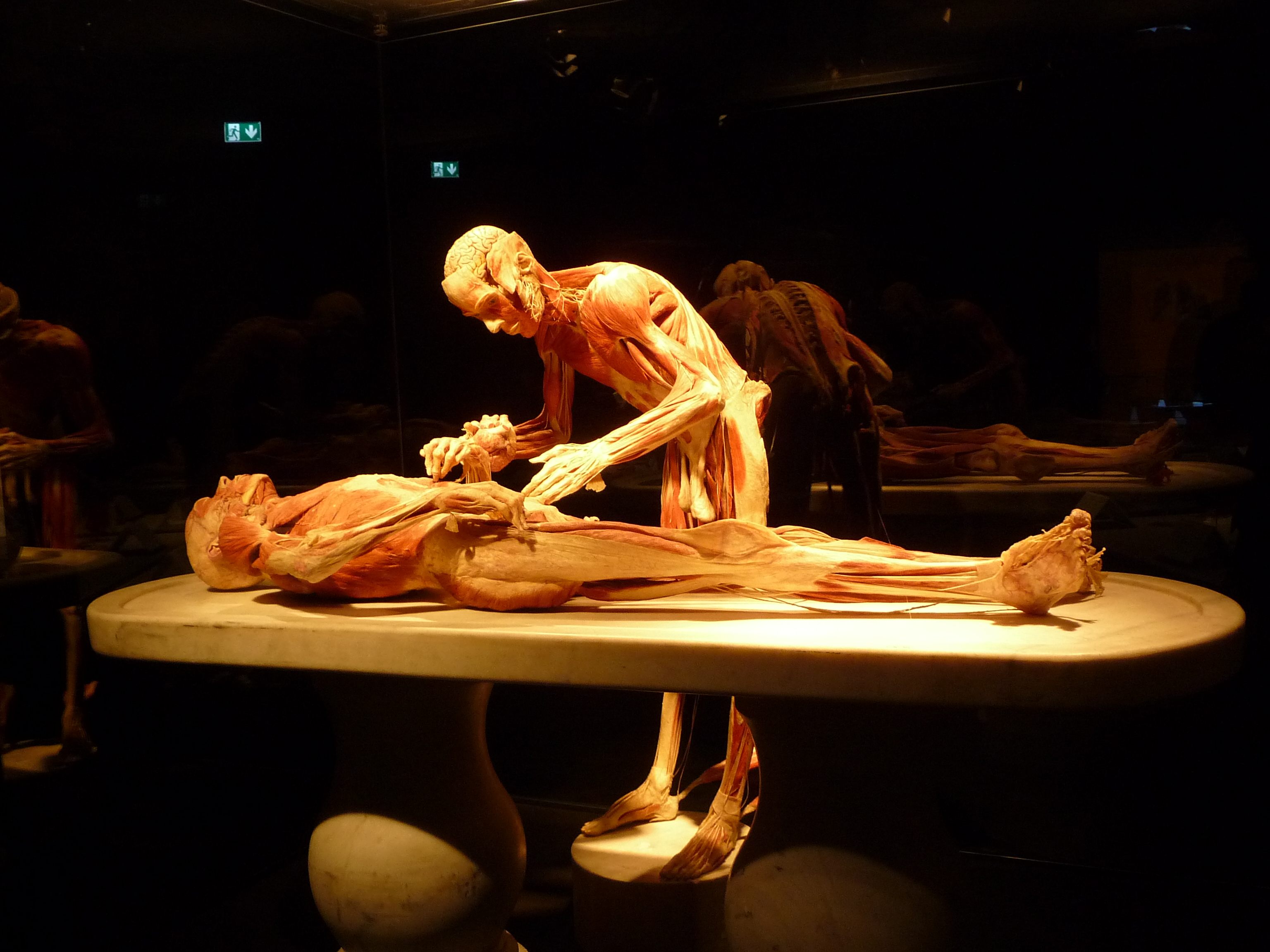

Museums have long been eager to exhibit human remains—one part history, one part morbid curiosity. Travelers around the globe can see bog bodies at the British Museum, a Viking who was cremated in his ship in Denmark, or an intact Neolithic burial at the National Museum of China. A new exhibit titled Mummies is currently showing at New York’s American Museum of Natural History. The blockbuster exhibit Body Worlds—which features plastinated cadavers set in theatrical poses—has been circling the globe since 1995. Forty million people have seen Body Worlds, more people than there are Canadian citizens.

But museum visitors today are unlikely to see Native Americans’ earthly remains. The Denver Museum of Nature & Science, for example, took its last Native American skeleton off of display in 1970. The lack of Native American remains on exhibit isn’t due to a shortage—U.S. museums alone still hold more than 100,000 Native American skeletons in storage areas.

When many museums continue to exhibit the dead from cultures around the world, why are Native American skeletons treated so differently?

In the 15th century, the world was a secret becoming known. European explorers, fed by the voracious colonial appetite to conquer the globe, came across previously unimaginable places that left them amazed and mystified. Europe was the center of their universe, so they were captivated by their first encounters with the Himalayas and Victoria Falls, hippopotamuses and dodos. They also stumbled upon cultures—alive and from the past, from the Maori to the Aztecs—that were, to them, exotic and baffling.

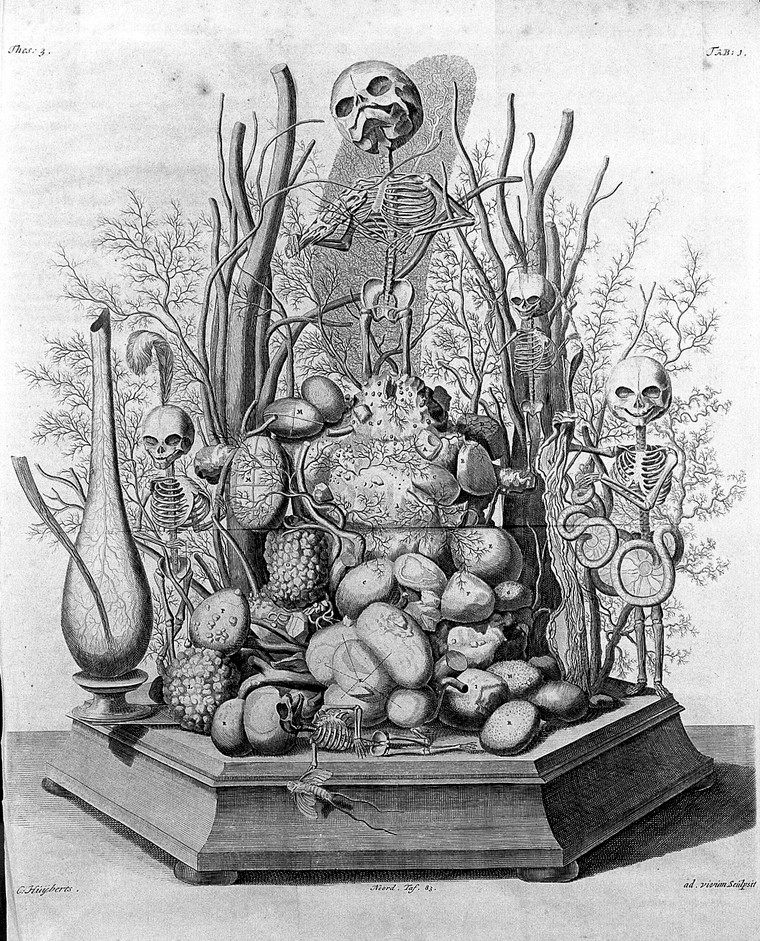

The birth of science provided one way for Europeans to unravel the mysteries of the world’s wondrous diversity. Early scientists sought to collect curiosities (these, troublingly, sometimes included people), to document and classify them. Nobles and scholars would then display their finds in cabinets for European viewers to contemplate. These exhibitions foreshadowed the modern museum’s tension between education and entertainment. Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch, for example, advanced the science of anatomy by developing new embalming techniques. But he also posed his human specimens—the skeletons of criminals and miscarried fetuses, which he gathered through his positions of doctor to the court and city obstetrician in Amsterdam—in bizarre tableaux to comment on life’s fleetingness. In one scene a skeleton plays a violin with a bow made of a dried artery, singing, according to Ruysch’s inscription, “Ah fate, ah bitter fate.”

In the mid-1800s, when museums evolved out of the cabinets of curiosity, skeletons remained an integral part of their displays. The interest in the remains of indigenous people was encouraged by early scientists, who studied human skulls in an attempt to prove their belief that Anglo-Saxons were racially superior.

In the United States, collectors focused on Native American skeletons. Native peoples had lived across the Americas for millennia, so their burials blanketed the continents. They were ripe targets for collectors, who gathered them in farm fields and in the path of construction projects. Native tombs also weren’t afforded the same respect or legal protections given to white graves. Native American burial grounds were emptied.

For example, the “father” of physical anthropology, Aleš Hrdlička, spent the summer of 1910 in Peru. He reportedly collected 3,500 skulls and skeletons. “One would think that to ravage the graves and carry away the bones of almost anybody’s ancestors would be a somewhat dangerous business,” a 1911 magazine reported from an interview with the scientist, who then worked at the Smithsonian. “But Dr. Hrdlička shrugs his shoulders.” In his long career, Hrdlička amassed the remains of more than 15,000 people.

Some of Hrdlička’s collections even more clearly violated the dignity of indigenous people. In 1902, Hrdlička was traveling in northern Mexico when he came across a massacre site of Yaqui Indians, killed by Mexican federal troops. He described finding 64 bodies, including women, children, and a baby. He chopped off the heads and hands of 12 victims. Hrdlička only lamented he could not obtain more. “Most of the skulls,” he later wrote, “whether from a peculiar effect of the Mauser cartridges or from the closeness of the range, were so shattered as to be of no use.” The Yaqui’s remains were sent to the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Native Americans had long tried to prevent the theft of their dead. But it was not until the 1960s, in the wake of the Civil Rights movement, that activists turned collections into a question of conscience: Why were U.S. museums filled almost exclusively with the bones of Native Americans? “When a white man’s grave is dug up, it’s called grave robbing,” as the Tohono O’odham activist Robert Cruz said in 1986. “But when an Indian’s grave is dug up, it’s called archaeology.” Native Americans chained themselves to exhibit cases, attempted citizen arrests of professors studying bones, and protested at archaeological sites.

Their objections boiled down to spirituality, racism, and consent. Native Americans from a range of tribes and regions agreed that museums were violating their religious freedom by not allowing them to spiritually care for ancestors; that the disproportionate number and display of Native Americans was steeped in a history of racism; and that Native Americans never gave consent for their dead to be disturbed. “The problem for American Indians is that there are too many laws of the kind that make us the archaeological property of the United States,” as the Cheyenne/Muskogee activist Suzan Shown Harjo wrote in 1989, “and too few of the kind that protect us from such insults.”

These arguments finally gained traction in 1990, when the U.S. Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which created a process for tribes to claim ancestral remains and artifacts. So far, museums have returned more than 50,000 Native American skeletons for reburial. In 2009, the body parts Hrdlička pilfered from Mexico were returned.

In contrast, a repatriation movement for Britain’s bog bodies, Vikings, or Neolithic Chinese skeletons has not really happened. The story of the most famous of all museum possessions—the Egyptian mummy—is a case in point.

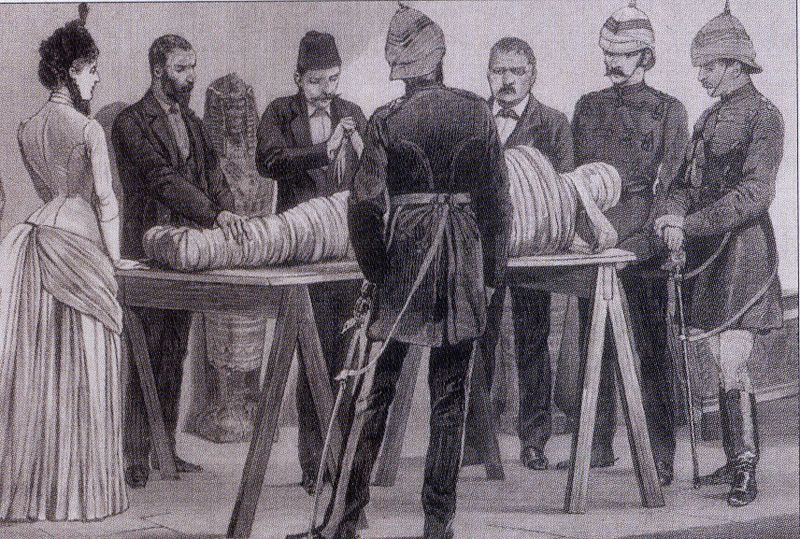

Egyptomania was born after Napoleon conquered North Africa in 1798, introducing Europeans to the treasures of the pyramids. Quickly, ancient Egyptians were turned into a fantasy of exotic otherness. Romantic poets and later the Victorians extolled the pharaohs for their beauty, ingenuity, and power. The need to directly experience this past turned to human remains. As Egypt became a common tourist destination in the 1800s, local dealers eagerly sold mummies as souvenirs. Public “mummy unwrappings” became commonplace in London, Paris, New York, and beyond. The Denver Museum’s mummy arrived in Colorado in 1904 when a local businessman returned home from a trip to Egypt.

Like the treatment of Native Americans, the collection of Egyptian skeletons is rooted in colonialism and a disregard for the wishes of the dead. But, while living Native Americans claim descent from their continent’s first peoples, the Islamic communities of Egypt do not claim continuity with the people who built the pyramids. And even if they did, mummies were gathered to glorify ancient Egyptians while Native American skeletons were long collected to dehumanize indigenous peoples. The modern-day Egyptian government has given its consent for the excavation of tombs.

The few demands for the return of ancient Egyptian heritage from Europe are based on nationalist arguments rather than religious freedom and human rights. Consider the new Grand Egyptian Museum, which will open in 2018 at the footsteps of the Giza pyramids, and present all 50,000 objects found in King Tut’s tomb, and hundreds of other funerary objects and remains. The museum will be a repository for looted items reclaimed from other countries. But the government doesn’t question that these returned pieces belong in a museum to serve an international and national public.

“We’ll be able to welcome guests from all over the world,” the museum’s General Director, Dr. Tarek Sayed Tawfik, said, “but mainly the Egyptians, because we want the new Egyptian generations to [have] pride in their ancient culture.”

So, why and when is it okay to display the dead?

The answer lies in how remains were collected and their connection to living people today. Viking warriors, ancient sacrifice victims preserved in England’s bogs, and China’s first farmers were all excavated with either the permission of descendants or from governments if no descendants are known.

When controversies erupt over exhibiting the dead, it’s likely because an institution has violated one or more of these concerns. In the early 2000s, Body Worlds was upbraided because of allegations that the corpses it was displaying were those of executed Chinese prisoners. Today, Body Worlds is largely uncontentious; it now only exhibits bodies donated by individuals who gave their explicit permission to have their corpse splayed open for all to see.

For Native Americans, the collection of their ancestors for museums has been an affront to their sense of dignity and spiritual beliefs. The repatriation of these remains is perhaps a minimum concession to that sense of self, culture, and continuity. As Apache/Nahuatl activist José Rivera once asked, “Do we have to be dead and dug up from the ground to be worthy of respect?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook