The 1930s Film Parodies Starring Only Dogs

The “Barkies” were popular with audiences, but drew ire from animal welfare groups.

The early sound era of film was like the Wild West when it came to making movies. It was into this experimental milieu that a series of short films that used all-dog casts was produced between 1929 and 1931.

Professionally trained canines were the stars of the “all-barkie” Dogville Comedies. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer produced the nine shorts as parodies of Hollywood’s hits. The films were shot with silent film and dubbed over with human speech, utilizing the voices of the creators Jules White and Zion Myers, as well as their colleague Pete Smith. According to Jan-Christopher Horak, the director of UCLA’s film and television archive, it is likely that other contracted MGM actors and actresses also lent their voices to the films, although none of that work was credited.

To a modern viewer, it can be hard to tell who the audience of these films were. It might seem like a canine cast is best suited for children, but the plots were often mature, featuring adultery, murder, and even cannibalism.

So how did these films come to be made? To understand that, one must also understand the way the studios were operating in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In this era, shorts would play before a full-length feature. They were primarily produced by independent companies and distributed through the studios. As the popularity of the shorts grew, studios brought on some of those independent producers to develop in-house work.

In 1929, according to film historian Rob King, MGM hired Jules White and Zion Myers to organize their new short subjects department. White had close connections in Hollywood. In King’s recent book Hokum!, he writes that Jack White, the older brother of Jules, was a top comedic shorts producer who helped Jules secure work as an assistant film editor before being recruited by MGM. A young Myers began working at Universal as a secretary in the early 1920s, when his sister Carmel was a rising silent film star. One of his co-workers there was Irving G. Thalberg, who would go on to become a legendary figure in American filmmaking. When Thalberg became an executive at MGM in the 1920s, Myers was able to secure a job at the company as a shorts director.

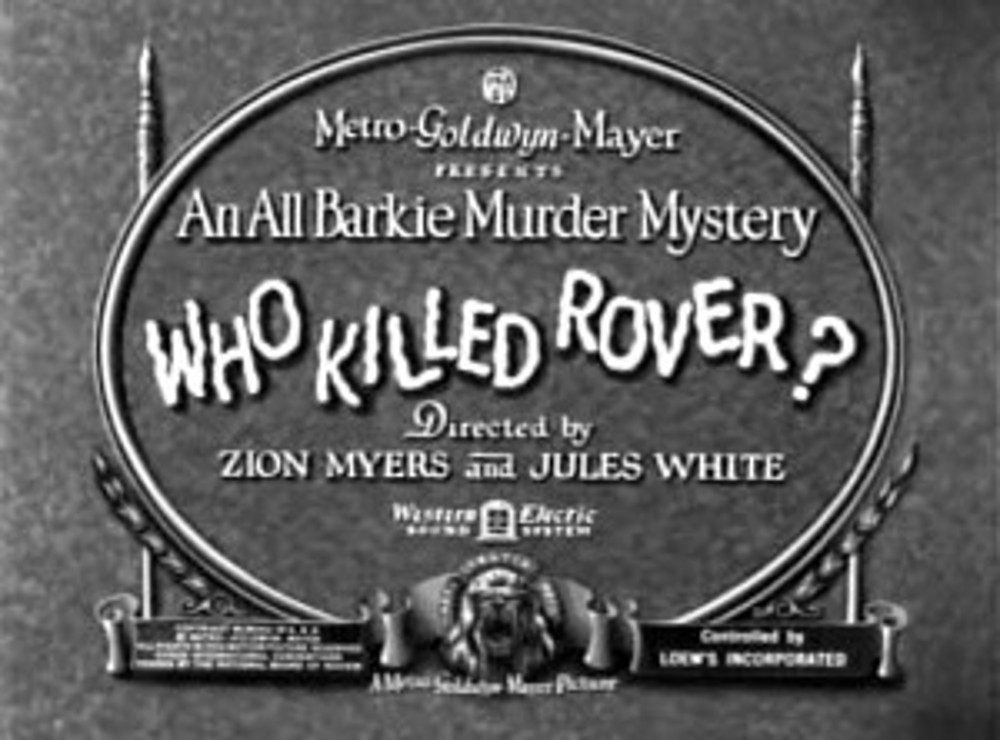

The Dogville shorts started with 1929’s College Hounds, a parody of Buster Keaton’s College that features a huge doggie football game. The next film was Hot Dog, about a murder in a seedy cabaret after a jealous husband finds out his wife has been cheating on him. The subsequent films all had equally punny names. There was the murder-mystery Who Killed Rover? and a Broadway parody called The Dogway Melody. Those were followed by The Big Dog House, All’s Canine on the Western Front, Love Tails of Morocco, Two Barks Brothers, and Trader Hound, a riff on MGM’s Trader Horn.

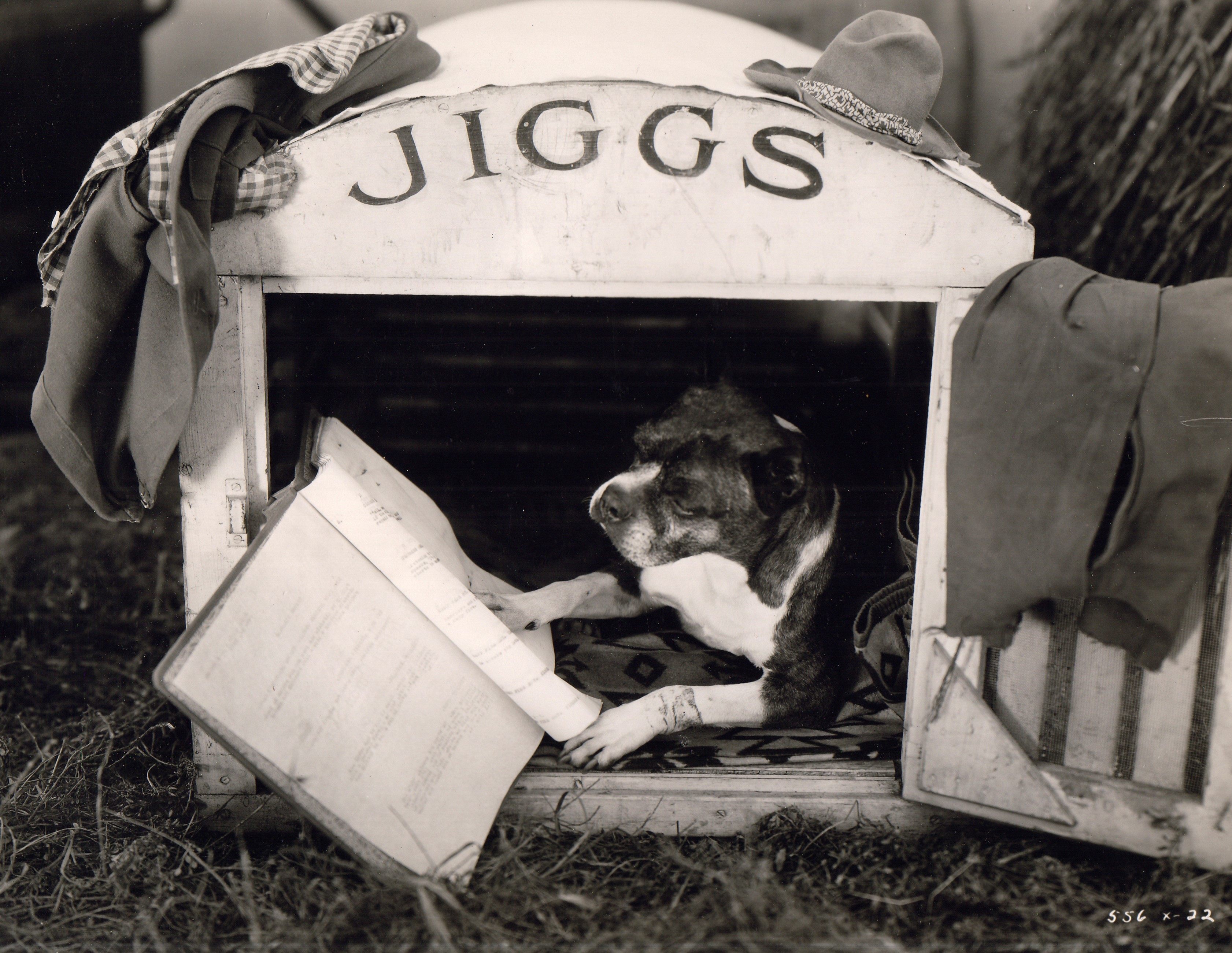

Some of the dogs came trained from renowned Hollywood animal trainer Rennie Renfro. Renfro had a ranch in Van Nuys where he reportedly trained roughly one hundred dogs for films over the course of his long career. Renfro worked closely with Myers and White to direct each short. Since they shot on silent film, the directors often shouted their commands to elicit the desired behavior from the dogs.

Other techniques were utilized as well, especially when it came to making the canine performers appear as if they were speaking. According to a January 1931 article in Popular Science Monthly, a director or Renfro himself would stand in front of a dog and wave various lures to focus the canine’s attention. The human would then open his hand repeatedly to entice the dog to open its mouth. Another method to imitate speech involved giving the dogs toffee to make them chomp.

The same Popular Science Monthly mentions the directors’ preference for stray and mixed-breed dogs “because they are not high strung and can get along better in groups than the animal ‘prima donnas’ of breeding.” The directors also used “veteran” animal actors, as they were less likely to miss cues or run off set altogether. Rumors have long circulated that those veteran dogs, including Renfro’s beloved Buster, received special treatment, including their own waiting areas, exercise tracks, and air conditioning, which was rare even for human actors at the time. But these claims cannot be verified.

Although shorts were typically not reviewed, the Dogville Comedies appear to have been well-received based on trade papers of the time. According to Warner Bros., “a nationwide theatre owners poll in 1930 rated the Dogvilles as the best short subjects over more legendary comedy and musical series.”

Even Jules White would later say that his favorite project of his entire career was “the dog things.” “All the stars at MGM would come over and watch us film them,” he said in a 1982 interview with The Los Angeles Times. He recalled that Greta Garbo liked to admire the cute dogs and was a frequent visitor to the set.

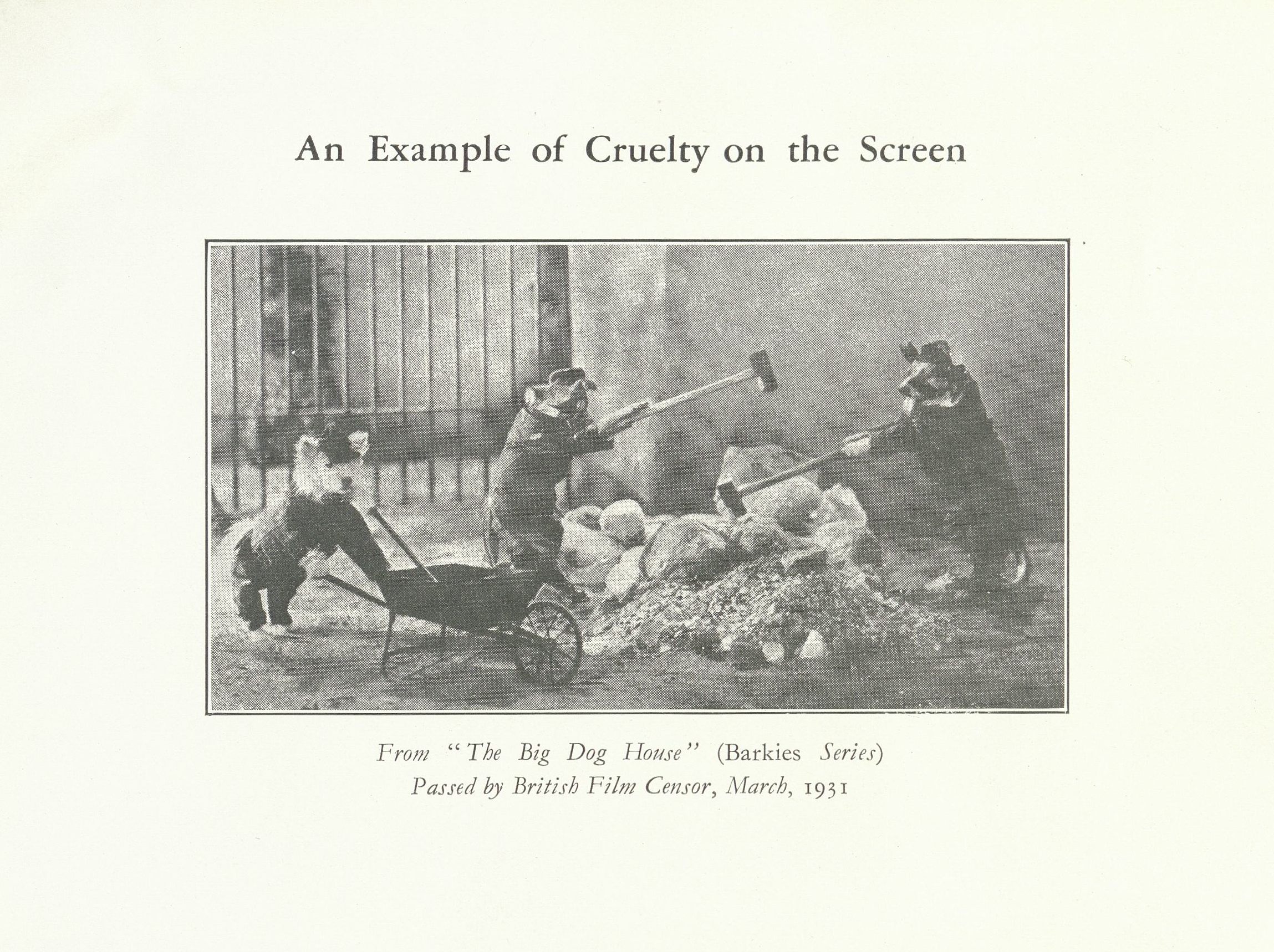

But not everyone was charmed by the “Barkies” and a backlash ensued. The dogs do not look comfortable as they walk on their hindlegs in stiff costumes, apparently held upright by piano wire. The Performing and Captive Animals’ Defense League wrote to the British Board of Film Censors to protest the release of these shorts. Several films in the series were thus banned by the British censor citing animal cruelty.

All-animal casts were not entirely novel. Released between 1923 and 1924, Dippy-Doo-Dads were Hal Roach-directed silent films featuring monkeys as the stars. A smaller company called Tiffany created a series of chimp comedies in the early 1930s using the same template as the Barkies. They may have been the product of sibling rivalry, as they were actually produced by Jack White, brother of Jules.

The creators stopped making the Dogville Comedies in 1931 after the controversial Trader Hound, banned by U.K. censors for its hints at canine cannibalism. White and Myers were offered other jobs developing the shorts department at Columbia Pictures, where White went on to make film history with the Three Stooges. Myers continued directing and writing comedic shorts and films, even writing the scripts and creating stories for some of the Stooges productions that White directed, such as 1948’s I’m a Monkey’s Uncle.

Today, the Barkies find themselves relegated to a footnote in the history of early talking pictures. But for almost two years, man’s best friend was also the silver screen’s biggest star.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook