Donald Trump Can’t See Through Dirt

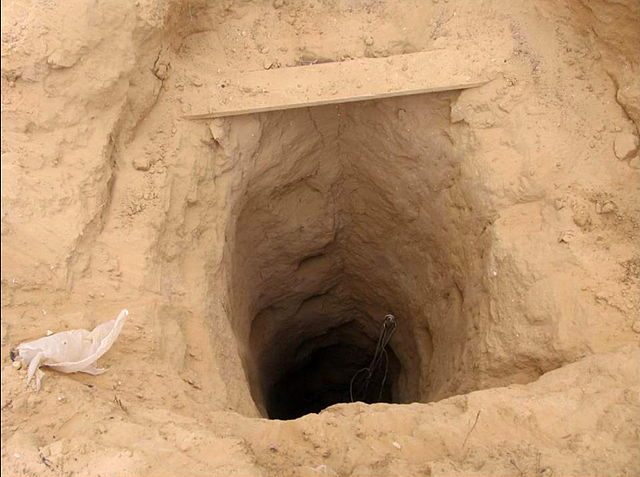

A smuggling tunnel in Gaza (Photo: חובבשירה/Wikimedia)

Presidential candidate Donald Trump wants to build a wall along the border of Mexico and the U.S., and although there are many possible objections to that plan, there is one that has not been discussed enough.

Tunnels.

There are tunnels under the United States border with Mexico. There are tunnels under Israel’s border with Gaza. Illegal, underground, cross-border tunnels have been found between Ukraine and Slovakia, Turkey and Syria, Hong Kong and China. Some of these tunnels are large and well-equipped: one tunnel that crossed the U.S.-Mexico border had an elevator built into it.

Starting in the 1990s, the U.S. border patrol started finding smuggling tunnels running under the border. Since then, the problem has grown, and the border fence that’s been erected along parts of the border only exacerbated the problem. In 2012, the Department of Homeland Security reported that there had been an 80 percent increase in tunneling since 2008, and in the winter of 2015, enforcement officials found a tunnel 905 feet long, the longest tunnel ever discovered in the Tucson, Arizona area.

After two decades of practice, drug organizations in Mexico are very, very good at building tunnels. And tunnels are very hard to find.

Proponents of a border wall are not much bothered by this. “We can mitigate the tunnels by making our walls and fencing wide with a road in the middle, like the Israelis build, “ says William Gheen, the leader of Americans for Legal Immigration PAC, who is amenable to the wall idea. “We can also place sensors on our walls and fences to alert us to tunnel digging activities.” When asked about the possibility that people would simply go under the wall he proposed, Trump argued that “seismic and other equipment could detect and stop any underground tunnels,” the Washington Post reported.

Even with today’s best technology, detecting tunnels using technology is difficult, expensive, and far from reliable. But one Israeli company, just this past summer, may have figured out how to do it.

A drug tunnel in Arizona (Photo: DEA)

The border patrol has tried to use technology to find illegal border tunnels for many years. In 2009, the Department of Homeland Security launched a Tunnel Detection Project, to improve its ability to find tunnels without relying on police work or happenstance. The department’s advanced research division would use “sophisticated ground penetrating radar” to scan the ground and identify tunnels, which could then be monitored or destroyed.

But making that sort of technology work in the field is difficult, and in 2012, the Inspector General’s office reported that U.S. Customs and Border Patrol “does not have the technological capability to detect illicit cross-border tunnels routinely and accurately.” The border patrol’s initial research into existing technology had found that no commercially available system fit the agency’s needs. One of the main issues is that tunnel detection technology is hard to use covertly: any efforts to detect a tunnel could alert smugglers, who CBP might want to detain, rather than scare off, to the operation. On top of that difficulty, the technology available today cannot reliably find tunnels by scanning the ground.

Why is it so difficult to find a tunnel? “Nature has made soil very good at keeping secrets,” says Carey Rappaport, a Northeastern University professor who heads the Center for Subsurface Sensing and Imaging Systems. The best way for human beings to get a sense of what’s happening underneath the ground, besides just digging a hole, is to send down waves that will reflect back with some information. Tunnel detection technology might rely on sound waves, microwaves, or even cosmic rays. When these waves hit air—which would be in ample supply in a tunnel—they behave differently than when they hit soil, and by analyzing how these waves behave, it should be possible to identify the big, empty spaces that tunnels create underground.

The problem is that there is a lot going on underground besides just tunnels snaking through soil. “There are layers of rock. Tree roots. Under the topsoil, there’s not such nice soil underneath,” says Rappaport. “All these things will mix the signal up and give a false alarm.” The picture that ground-penetrating radar or other technologies deliver is far from clear: Rappaport compared the experience of trying to find a tunnel in this noise to trying to find one particular disco balls in a room full of disco balls, using just a flashlight. “You can rule out some things,” he says. “But there’s a lot of light bouncing around, and picking out the light that you’re looking for is a challenge.”

The entrance to a tunnel in Gaza (Photo: Israel Defense Force/Wikimedia)

Until this year, these technical challenges had kept any massive tunnel detection system from being deployed. But earlier this year, media outlets in Israel started reporting that a defense company there called Elbit Systems had created a tunnel detection system that was both effective and reliable—no false alarms.

There are few details available about this technology. It’s based on a system of sensors and algorithms that parse the sensor data to flag underground activity. That’s about all the information that’s available publicly. When asked what makes this technology more effective than what’s been tried in the past, a spokesperson for Elbit Systems replied, “Unfortunately we will not be able to give details about the technology.” But the Israeli government has enough confidence in it that the pilot program is being expanded to cover the 51-kilometer border between Gaza and Israel, at a cost of $1 to $2 million per kilometer, Jewish Business News reported.

“Having better algorithms always helps,” says Rappaport. The more that the particular geological conditions of the area can be taken into account, for example, the more accurate the results will be. And the Department of Homeland Security is taking a similar approach, collecting information on the geology of the 50 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border where tunneling is most common.

Even with excellent, functional detection technology for tunnels, smugglers will still burrow under the border. “Tunnels will always be a problem in certain areas,” Gheen, the immigration activist, says. Rappoport calls it “an incurable cancer.”

“There have been a lot of technological efforts to try to solve this problem,” he says. “But although the results are better and the devices are better, deep tunnels are a very effective way of hiding things.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook