The 19th-Century Secret Society Preserving the History of the West

The irreverent, all-male E Clampus Vitus commemorates overlooked people and events.

On the northern edge of Virginia City, Nevada, where silver once honeycombed the rocky slopes like arteries beneath the skin, lies a historical plaque commemorating the burial site of Mary Jane Simpson. Like other miners of the mid-19th century, she lived her days in darkness, working the miles of treacherous tunnels beneath the town. But Simpson had a few things they didn’t, starting with four legs and a tail.

“Mary Jane Simpson was a mule in the mine in Virginia City,” says Virginia City resident and history buff Ken Moser. “This is an absolutely true story. She was incredibly intelligent, and she had a driver, but she didn’t really need him to know her way around. She understood all of it, she knew all the bell signals and lights.”

So when Simpson was killed in the boomtown’s Great Fire of 1875, the miners placed an inscription at her grave: “The within was only a mule, still she was nobody’s fule [sic]. Stranger tread lightly.” Over a hundred years later, in 1993, Simpson’s death was made official, with a permanent plaque installed by the not-so-secret fraternal organization E Clampus Vitus (ECV).

Mary Jane Simpson’s is just one of 1,641 obscure histories from Virginia City and the whole of the American West commemorated by E Clampus Vitus, stories that despite never appearing in official histories, nonetheless shaped not just those early days but everything that followed.

E Clampus Vitus was one of several brotherhoods that swept as many as 40 percent of American men into their fold during the “golden age of fraternalism” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, societies that included the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, the Knights of Columbus, and the Loyal Order of Moose. Men joined for a number of reasons. Not only did fraternal organizations provide social opportunities, but they also offered insurance, financial aid, business connections and, above all, political clout. Women, unsurprisingly, were not permitted to participate.

E Clampus Vitus emerged from West Virginia mining country sometime in the 1840s or 1850s; by 1853, the organization was oozing like tar across Doddridge County, according to early twentieth-century journalist Boyd D. Stutler. Founder Emphraim Bee traced the origins of the order to a Chinese descendant of Confucius. But, writes Stutler, “it was burlesque”—a farce and parody—“pure and simple.” Everything about E Clampus Vitus, from its heritage to its rituals, was a caricature of the self-serious fraternal organizations of the day.

Weary miners, many of whom may have felt out of place in the prim Oddfellows and Freemasons of the day, flocked to E Clampus Vitus in search of a light-hearted escape and the additional security a brotherhood could provide in a dangerous industry. Initiates today still “swear to take care of the widows and orphans—especially the widows.”

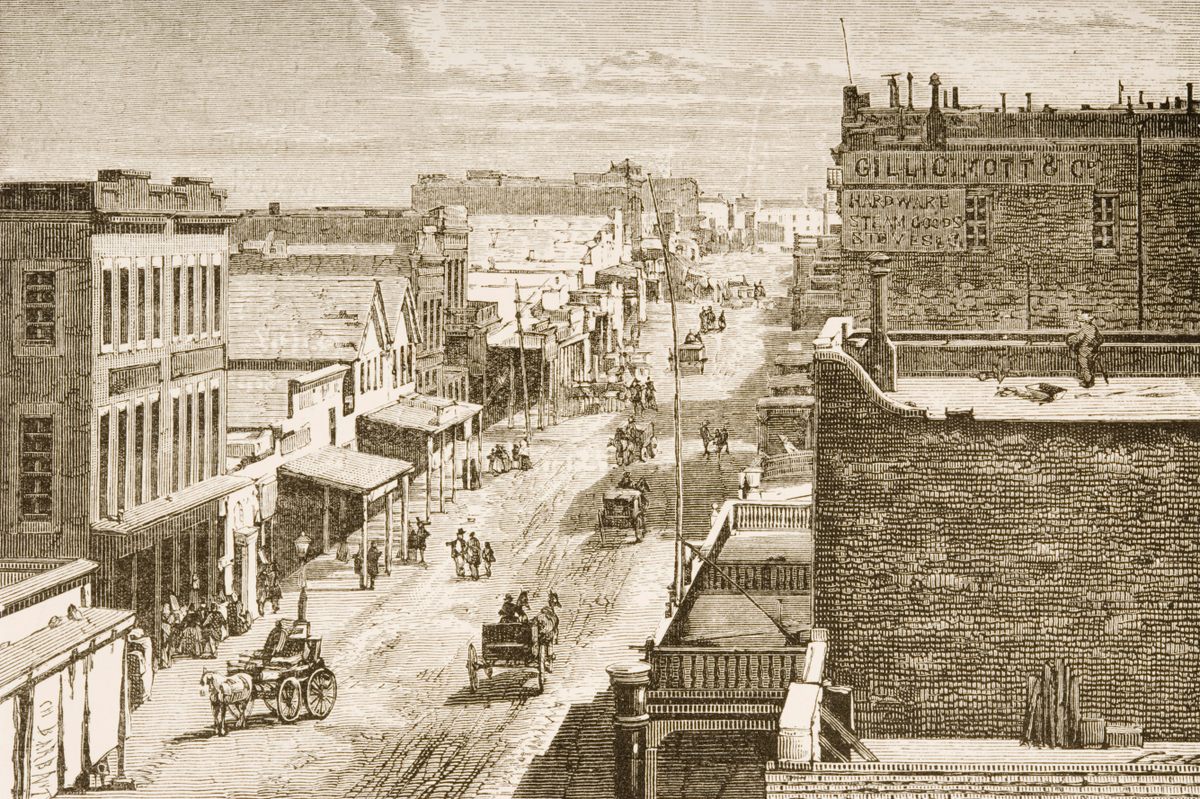

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1849, miners descended like ravenous mosquitos on the rigid mountain spine separating California and Nevada. E Clampus Vitus descended with them. Like a backdraft, it swept over dusty, half-baked mining camps in far-flung outposts like Mokelumne Hill, Sonora, Mariposa, and Murphys.

Whiffs of their absurd traditions weaseled their way into newspapers across the state in the 1850s and ‘60s, some of which were collected in Lois Rather’s 1980 book Men Will Be Boys: The Story of E Clampus Vitus and Seth Slopes’ 1979 E Clampus Vitus: Now & Then.

Instead of elegant badges, they pinned themselves with tin can lids. Instead of waving a flag, they flew a hoop skirt. They drank liquor—a lot of it. Initiates, referred to as “poor blind candidates,” were subjected to a series of humiliating tasks like climbing greased poles and being dipped into a vat of water by rope from the top of a church steeple. One memorable 1861 E Clampus Vitus parade sent 54 members in black masks and gowns and white sashes through the muddy, rain-soaked streets of Downieville near the California-Nevada border. The Noble Grand Humbug—a leadership position that rotated among chapter members—wore pink.

“E Clampus Vitus actually had quite a bit of clout,” says Moser, an ex-Noble Grand Humbug in Virginia City. “In order for people to do business they’d have to become a member to be considered. At one point, the California legislature was closed for a few days so that its E Clampus Vitus members could travel to the big convention.”

Almost every mining town in California had an E Clampus Vitus lodge in the mid-nineteenth century, Rather writes, so when the largest silver deposit ever found in the United States, the Comstock Lode, was discovered in Virginia City in 1859, an ECV chapter shouldn’t have been far behind. No one knows why it never made it in those early days, but E Clampus Vitus didn’t skip over the boomtown altogether.

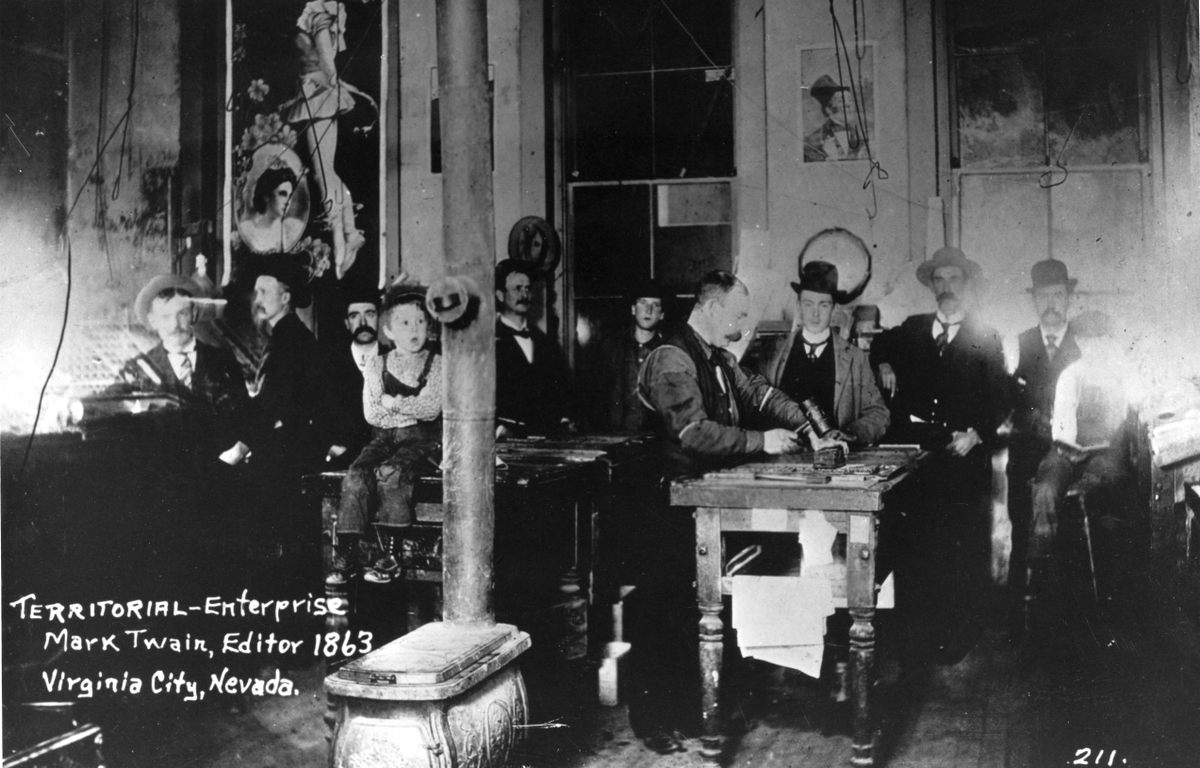

When he was hired at Virginia City’s newspaper in 1862, Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, had already gone through the rites of initiation in Angel’s Camp in California. It was there, at an ECV meeting, that he heard the tale he would turn into his 1865 short story The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County—or so the legend goes.

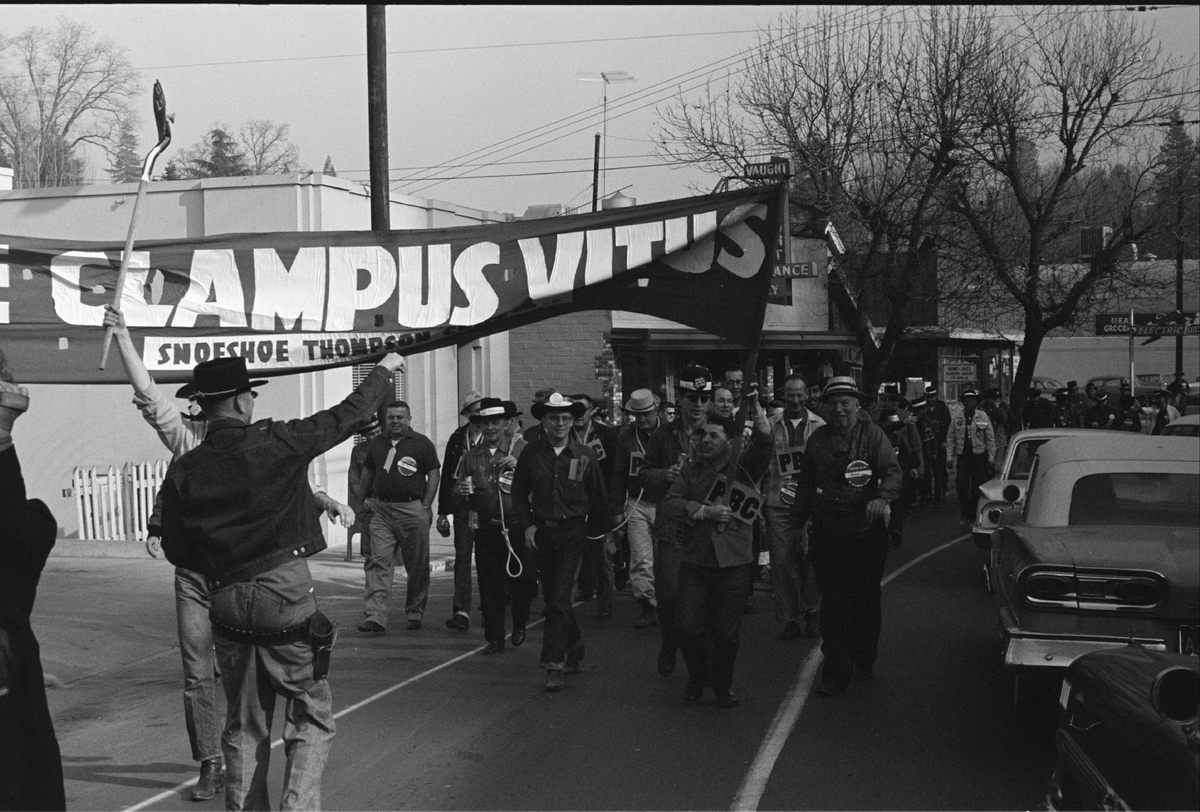

E Clampus Vitus fell out of favor slowly around the turn of the twentieth century. By the 1920s the once-robust brotherhood was essentially defunct. It was the knowledge of Adam Lee Moore, the last Noble Grand Humbug of the Sierra City Balaam Lodge No. 107,304, that saved the group from obscurity. When it started anew in 1930, E Clampus Vitus was just as absurd as it once was, but there was a new objective afoot: to recognize the history of the West which, like ECV had itself, was fading fast.

As if making up for the brotherhood’s absence in the days of the Comstock Lode, Virginia City chapter, Julia C. Bulette #1864, was the first lodge to be reborn on the Nevada side of the Sierra. They’ve erected a historical plaque almost every year since, illustrating the minutiae unique to Virginia City through time. It’s the only historical fraternal order whose membership is growing, according to Moser. He’ll be attending the confirmation of two more chapters—one in Spokane, Washington, the other in Lovelock, Nevada—just this summer.

Miners no longer make up the majority of the membership of E Clampus Vitus. Today, the brotherhood is predominantly made up of working- and middle-class white history buffs—teachers, firefighters, construction workers, small business owners and the like. Some join because their father or uncle or grandfather was a member; others join for the shenanigans or the beer-swilling, boy’s club environment or just for the historical preservation activities.

“A lot of people really see their identity as being part of the Clampers as really important in life,” says Matthew “Metric” Ebert, Virginia City’s previous Noble Grand Humbug. “People want to feel like they’re part of something. We’re a history gang with monuments.”

The historical figures and events ECV chooses to recognize are selected annually by the Noble Grand Humbug and approved by the chapter as a whole. In Virginia City, a number of them are dedicated to the intense but short-lived mining madness that built, and rebuilt, the town.

“The one we put up last year is on the Yellowjacket Fire in Gold Hill during the mining days,” says history teacher and current Noble Grand Humbug Travis Stransky. “It killed a bunch of miners and that fire burnt down there for some time.” They placed the monument on the side of the 1862 Gold Hill Hotel; its saloon was once frequented by Clemens, and rusted out mining equipment and rotting wooden scaffolding still sit among the scrub brush on the property.

The monuments contrast sharply with towns in which “a lot of preserving history has been done by wealthy white men,” says Ebert. In town, where horses occasionally wander onto A Street in the lingering afternoon heat, ECV plaques dot the Western false-front architecture. Many plaques recognize the lives or work of those on the margins of society, including Chinese laborers and sex workers. Julia C. Bulette, for whom the Virginia City chapter is named, was among the latter: a sex worker, accomplished seamstress and honorary member of the fire company who was brutally murdered in 1867.

This year, the Virginia City Clampers will commemorate the filming of the 1961 western, The Misfits in the Odeon Hall in Dayton, Nevada. “I’m a huge fan of old school Hollywood and to this day there’s nothing in downtown that says anything about the filming,” says Stransky, who selected and researched the site for approval by the chapter. “I tracked down the owner of the building in which Marilyn [Monroe’s] famous paddle ball scene was filmed.” In July 2022, they’ll dedicate the plaque, another arcane piece of the past rescued by E Clampus Vitus.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook