Elizabeth Freeman Demanded Her Freedom—and Helped End Slavery in Massachusetts

A monument to the formerly enslaved woman will soon stand in the town she called home.

In 1773, a group of prominent citizens in the Western Massachusetts town of Sheffield gathered at the home of a farmer named John Ashley to draft what would become known as the Sheffield Resolves. The document, which argued against British tyranny and in defense of individual rights, began with the words, “Mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent”—perhaps informing the text of the Declaration of Independence three years later. But the fiery assertions laid out in Ashley’s upstairs study also had an impact on another form of tyranny, one taking place under Ashley’s own roof.

Ashley was the enslaver of at least five people, including a woman then known as Bett, who was likely listening as he and his friends discussed freedom and independence. Eventually, the contradiction would become untenable. In 1781, after Ashley’s wife wounded her on the arm with a red-hot fireplace shovel, Bett walked four miles to the home of Theodore Sedgwick, an attorney and future speaker of the US House of Representatives—and another signer of the Resolves—and asked him to represent her as she sued for her freedom.

Bett became the first Black woman to successfully sue for her freedom in the state, and the lawsuit directly contributed to the end of legal slavery in Massachusetts. But her achievement would become a historical footnote, even in the Western Massachusetts towns where she and her descendants made their home. Now, however, a handful of locals are working together to build a monument to this once-enslaved woman—and embrace a chapter of their region’s history that might have been more comfortably left in the past.

“I grew up in the Berkshires, but I never knew this story,” says Smitty Pignatelli, who represents Massachusetts’s fourth district in the State House of Representatives. Born in Lenox, just 17 miles north of Sheffield along the Housatonic River, Pignatelli learned about Elizabeth Freeman (as Bett christened herself upon gaining her freedom) during a local history event. In recent years, her story has been gaining more attention in and around Sheffield. The Col. John Ashley House, now a museum, is part of a local African American Heritage Trail, and since 2005 it has hosted an annual celebration on August 21, the date she won her lawsuit. But Pignatelli came to believe that Freeman deserved broader recognition.

“I realized a lot of my colleagues, including African American colleagues, hadn’t heard of her, either.” Pignatelli says. In 2020, the unveiling of a statue honoring Susan B. Anthony at her birthplace in nearby Adams gave him an idea, and he set about raising money for a similar monument to Freeman.

“I’m not a statue guy, but this felt different,” Pignatelli says. “This is a Black woman, 82 years before emancipation—with the courage she had, she deserves more than a park bench! And we don’t want the next Smitty Pignatelli growing up here not knowing this story.”

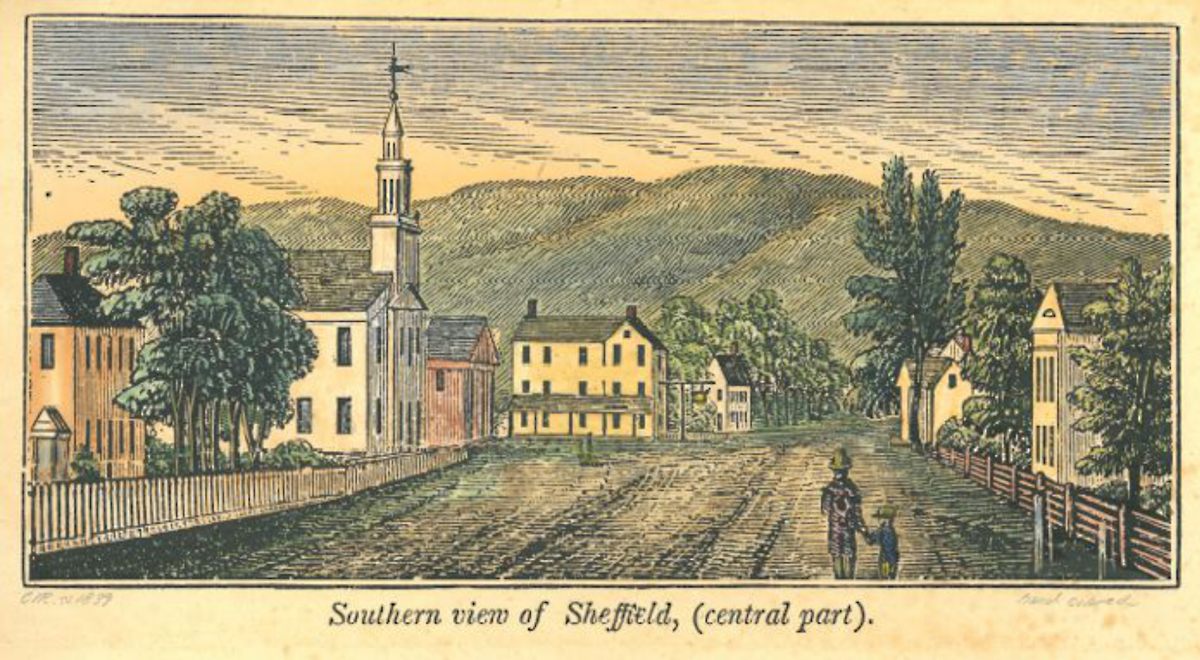

Joining forces with the Sheffield Historical Society and the Berkshire Taconic Community Foundation, Pignatelli secured state grants and recruited private funders to raise $200,000 for a 7.5-foot-tall bronze statue, commissioned from New Jersey sculptor Brian Hanlon, who is known for his lifelike memorials honoring sports icons, civil rights heroes, war veterans, and first responders. It will be unveiled this August at the center of Sheffield, next to the church Freeman attended and across the street from Sedgwick’s home.

“Everyone’s been super supportive of it,” says Paul O’Brien, president of the historical society. Members of the First Congregational Church of Sheffield voted unanimously to donate space for the statue, and the effort has gotten locals in this town of about 3,000 talking and thinking more about a troubling aspect of their history. “People say to me, ‘Well, how many slaves were there in Sheffield, and who were some of the other owners?’” O’Brien says. “There were church members who were owners—Ashley was not alone in owning slaves. It was a fairly common thing.”

In telling the story of American slavery, history books tend to focus on the South in the years before the Civil War, but while slavery was never a dominant feature of New England’s economy, many of its most prominent white families—going all the way back to Puritan leader John Winthrop—derived their wealth from enslaving Black and Indigenous people. Historians estimate that in the 1770s about 2 percent of Massachusetts’s roughly 250,000 residents were enslaved.

In New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America, Wendy Warren, a history professor at Princeton University, writes about the trade in slaves between colonies in New England and the West Indies, with New Englanders exporting captured Native Americans and importing enslaved Black people to work as farmhands, laborers, and household servants.

“When I ask my students to describe North American slavery, they inevitably bring up cotton, plantations, the U.S. Civil War, and abolition,” Warren writes, arguing that that impression is due to skewed history that focuses too narrowly on the antebellum South. “The clearing of trees, the planting of crops, and the catching of fish that enabled ‘New England’ to become a real entity, rather than a colonial dream, required labor, and in New England as elsewhere in the Americas, a not insignificant part of that labor was enslaved.”

Among the enslaved laborers who made New England what it is were Freeman and a man named Brom, whom she recruited to join her petition for freedom. They filed their suit, Brom & Bett v. John Ashley, Esq. in spring 1781. After Ashley refused a writ of replevin—a court order for the return of unlawfully held property—he was forced to appear before the Court of Common Pleas on August 21, 1781. Sedgwick’s argument for the plaintiffs rested on the assertion that the newly ratified Massachusetts Constitution had effectively outlawed slavery with the words, “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights…” The court agreed, ordering that Ashley release Freeman and Brom and pay them 30 shillings each in damages, plus court costs.

Brom’s life as a free man is unrecorded, but Freeman—after turning down a paid job offer from Ashley—would go on to work as a housekeeper and nanny for Sedgwick, whose children referred to her affectionately as “Mum Bett.” By 1803, she had saved enough money to buy a house and farm of her own in the nearby town of Stockbridge, where she settled with her daughter, son-in-law, grandchildren, and extended family. Two decades after Freeman died at about 85 in 1829, Sedgwick’s daughter, the novelist Catharine Maria Sedgwick, published a short biography of her childhood caretaker, quoting her as saying, “Any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me & I had been told I must die at the end of that minute I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman.”

Freeman got more than that one minute—and she did more than change her own life. Shortly after Brom & Bret was resolved, her case was cited as precedent in Quock Walker v. Jennison, a similar case in Worcester County, Massachusetts, in which an enslaved man had sued for his freedom. In a momentous April 1783 opinion, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice William Cushing declared slavery incompatible with the state constitution, as “there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature.” The decision for Walker marked the legal end of slavery in Massachusetts, making it the first state to abolish the practice outright. (Pennsylvania had enacted gradual manumission in 1780.)

“Freeman is part of the whole story—this is an American story, the movement that became the Civil Rights Movement,” says Wanda Houston, a singer and actress who is portraying Freeman in a one-woman show, Meet Elizabeth Freeman, by the Philadelphia playwright Teresa Miller. The play will be performed at the First Congregational Church of Sheffield, as part of festivities surrounding the statue dedication in August.

Born in Chicago, Houston has been a fixture in the Berkshire-area theaters since 2001, moving to the area permanently in 2011. She lives in Sheffield—“I love this little town and the people in it!”—and when she heard about Freeman, she realized she was “born for this role.”

“This is a story I’d never heard, even in Black history lessons,” Houston says. “There’s more of an African American presence here in the Berkshires than people realize. I know some things were politely hidden, at times, and no one needs to feel guilty about the history of slavery in New England, but this is the history, and it should be known. I am thrilled about making a difference in that, and in trying to get a story out there that people don’t know.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook