The Wire That Transforms Much of Manhattan Into One Big, Symbolic Home

The eruv, a nearly invisible holy boundary, must be intact every Friday.

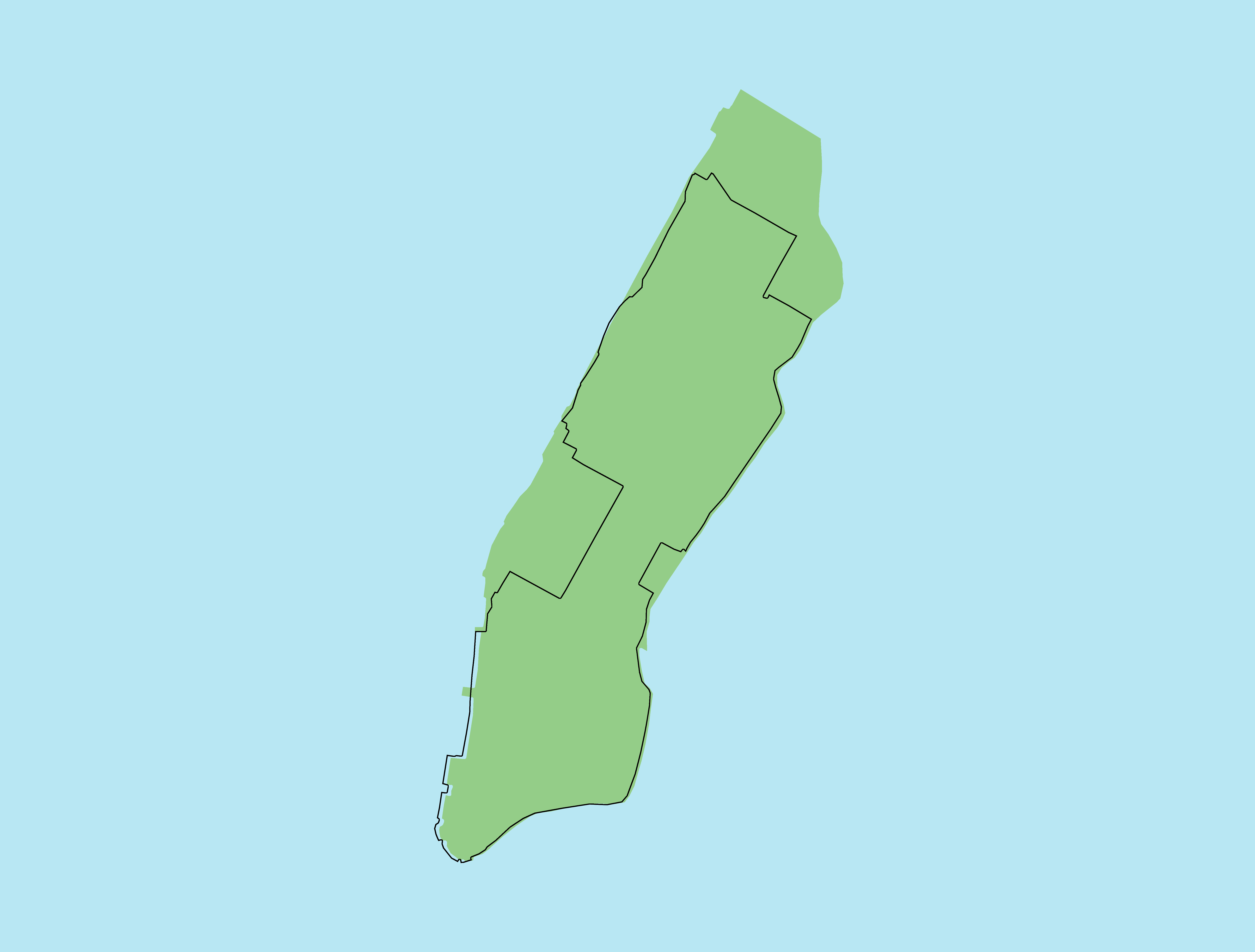

Every Thursday and Friday morning, Rabbi Moshe Tauber leaves his home in Rockland County, New York, at about 3:30 a.m. He arrives in Manhattan an hour later and drives the 20-mile length of a nearly invisible series of wires that surrounds most of the borough. He starts at 126th Street in Harlem and drives down, hugging the Hudson River most of the way, to Battery Park and back up along the East River, marking in a small notebook where he notices breaks in the line. Known as an eruv, the wire is a symbolic boundary that allows observant Jews to carry out a range of ordinary activities otherwise forbidden on the Shabbat.

Any necessary repairs must be finished before sundown on Friday, when Shabbat begins. The day of rest then lasts until the following day when there’s no more red in the western sky. Throughout that time, observant Jews are prohibited from performing many basic activities, and the observance of this law has been updated over time to reflect current technologies, such as cars, electricity, and keys. “Carrying from one domain to another,” or moving objects between public and private areas, for example, is forbidden. Eruvin (the plural of eruv) transcend this restrictive rule by serving as a symbolic border that links together many private spaces in the community, which in turn permits people to ferry around keys, children, and canes, or push wheelchairs and strollers.

But a single break in any part of the line voids that symbolic space. According to the 100 pages devoted to eruvin in the ancient Talmud, the boundary is only effective when the entire line is intact. And there are plenty of ways these breaks can happen. Sometimes it’s the elements, but more often construction is responsible. The wires, attached to telephone and light poles, can be severed or simply pushed down (the eruv must remain at the top of the pole) to make room for maintenance on other lines. And this is where Tauber comes in. “If they’re lousy they’ll just cut the lines and let it go,” he says. He’s been doing this carefully orchestrated monitoring since 2000. The repairs are “a secret operation,” chairman of the Manhattan Eruv Committee Rabbi Adam Mintz told the New York Post in 2015. That’s by design.

Tauber checks the lines so early in the morning in the interests of efficiency—driving around the island at any other time would be virtually impossible due to traffic. It was Mintz who suggested I go out with Tauber at “the ungodly hour,” but I opted to meet with him at about 8:30 on a Friday morning instead, at 110th Street and Lexington Avenue, where someone had removed the cap from the top of a light pole, leaving the eruv a few inches from the top. I watched as two cable workers made the repairs by snipping the wire and passing it through a hole at the top of the pole.

In Manhattan, the required repairs are almost always a thoroughly low-tech endeavor. Aside from the cherry picker used to get to the top of the poles, the only other necessary tools are a spool of wire and wirecutters. After 110th, I rode with Tauber down the Henry Hudson Parkway. He parked on a service road and ran off to tie a broken length of the wire back together. We then met back up with cable workers, on 58th Street and 11th Avenue, where the eruv wire was down for two whole blocks. One worker spooled out the line from the raised cherry-picker basket, while the other drove slowly down to 56th Street.

The eruv has only been down for the Shabbat once during Tauber’s tenure, when a 2010 snowstorm shut down most of the city on a Friday. Maintenance crews were unable to get to areas that needed to be fixed in time. For a while, the status of the eruv was reported by a Twitter account (it’s been inactive since last October) that essentially repeated itself on a weekly basis: “The Eruv is Up this Shabbat, October 13–14.” The account also notes November 1, 2012, when Hurricane Sandy caused damage to the eruv in 22 places. But everything was repaired in time for the holy day.

Eruvin have been around for 2,000 years, though Manhattan’s line has been in place, in some form or another, for just over a century. The term “eruv” is derived from the Hebrew word for “mixture,” and in Manhattan it’s a fitting title: The line encircling much of the island is a patchwork formed by 20 years of breaks and repairs. It’s only since the late ’90s that there has been a structured system for its maintenance. An early version surrounded the whole island, but no one seemed to know its precise boundaries, and everyone just sort of assumed someone else was in charge of maintaining it. When a group of rabbis in the ’80s took a boat around Manhattan to create a map, they realized that most of the wire was gone. Now it’s more tightly regulated, and subsidized by the community it helps to create.

Zachary Levine, Director of Exhibitions and Collections at the National Building Museum, says an eruv “creates a visual language that defines space.” The series of practically invisible wires becomes a necessity that “benefits the most vulnerable people of the community.” He sees it not only as a way for communities to come together, but also as a way for the more affluent to give back. The eruv is funded entirely by the Jewish community, with a considerable portion of that support coming from wealthy philanthropists.

For six days of the week, or to passersby outside the community, the eruv is just a simple, more or less invisible, set of strands across physical space. But during Shabbat, the holy day, it takes on an important meaning for those who rely on the symbolic border to expand the domain of their homes while staying true to their belief system. As Levine puts it, the eruv “doesn’t matter, unless it matters to you.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook