Classical Depravity: A Guide to the Perverted Past

Detail of the Borghese Vase (via Louvre)

“Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three,” wrote Philip Larkin wryly in his 1967 poem “Annus Mirabilis.” Antiquity thought otherwise.

Gods and mortals, men and women, satyrs and nymphs, all kaleidoscopically fell into and out of lust. Across the Mediterranean in the classical world, sexual norms were radically different to those in contemporary Western society. The phallus might well contend with the Parthenon as the symbol of classical civilization.

The Temple of Dionysus, Delos (via Gradiva/Wikimedia)

Ancient Athens was not only the brightest cultural light of antiquity, but also, as Eva C. Keuls puts it in The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens, “a society dominated by men who sequester their wives and daughters, denigrate the female role in reproduction, erect monuments to the male genetalia, have sex with the sons of their peers, sponsor public whorehouses, create a mythology of rape, and engage in rampant saber-rattling.”

Nor was Athens an exception. In Alexandria, in 275 BC, a 180-foot-long gold-plated phallus was paraded through the streets of the city, flanked by elephants, a rhinoceros, and a giraffe — and decorated, as the Greek Athenaeus noted, with ribbons and a gold star. Those who failed to join in such festivals enthusiastically were more likely to attract criticism than those who did:

Someone at the court of King Ptolemy who was nicknamed ‘Dionysus’ slandered the Platonic philosopher Demetrius because he drank water and was the only one of the company who did not put on women’s clothing during the Dionysia. Indeed, had he not started drinking early and in view of all, next time he was invited, and had he not put on a Tarantine wrap [women’s clothes], played the cymbals, and danced to them, he would have been lost as one displeasing to the king’s lifestyle.” (Lucian, Calumnies, 16).

Rome, needless to say, took these aspects of Greek culture and ran with them — the young Julius Caesar was known as the “Queen of Bithynia,” so fond was he rumored to be of cross-dressing. But that isn’t to say that there weren’t taboos, and strict and unforgiving moralities — or limits which most were disinclined to transgress. A benign drunken phallic procession was one thing — an emperor’s debauch could be quite a different matter.

Here are six sites from the perverted past — some have been shocking for over 2,000 years, while others were once upon a time no more controversial than the corner grocery-store.

VILLA JOVIS

Capri, Italy

Reconstruction of Villa Jovis by C. Weichardt (1900) (via Wikimedia)

In the northeast of Capri, atop a cliff looking out to sea, are the remains of a place of sexual legend. The mere mention of Villa Jovis, home of the Emperor Tiberius for many years, could made even the most debauched Roman blush.

It was completed in 27 AD. Tiberius retreated there from Rome, governing the Empire from behind its walls until his death ten years later. Tiberius was brilliant, depressive, and increasingly isolated — an ancient Howard Hughes, brooding on the world and disliking what he found. Secluded in Villa Jovis, his pastimes — reported and almost certainly exaggerated by hostile later authors — grew increasingly elaborate:

Teams of wantons of both sexes, selected as experts in deviant intercourse, copulated before him in triple unions to excite his flagging passions. The villa’s bedrooms were furnished with the most salacious paintings and sculptures, as well as with an erotic library, in case a performer should need an illustration of what was required. Then in Capri’s woods and groves he arranged a number of nooks of greenery where boys and girls got up as Pans and nymphs solicited outside bowers and grottoes: people openly called this “the old goat’s garden,” punning on the island’s name. He acquired a reputation for still grosser depravities that one can hardly bear to tell or be told, let alone believe. For example, he trained little boys (whom he termed tiddlers) to crawl between his thighs when he went swimming and tease him with their licks and nibbles. (Suetonius, Tiberius, 44).

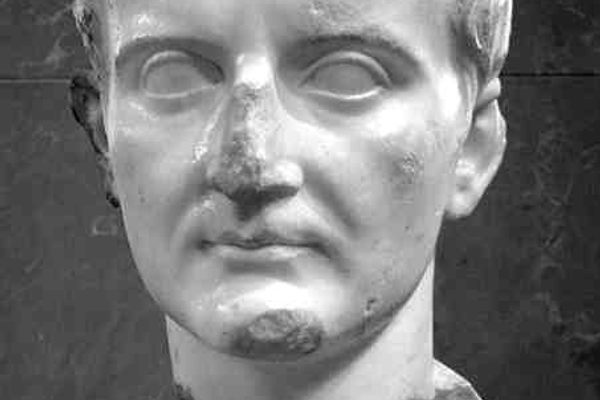

Bust of the Emperor Tiberius at the Louvre (photograph by Catchpenny/Flickr user)

Many of the most outrageous stories of Roman imperial excess are almost certainly invented; gossip spread by authors writing generations later. We should not put too much faith, for instance, in stories of Messalina, wife of the emperor Claudius, competing with a prostitute to see how many men each could have sex with in one night (Messalina won, with 25, according to Pliny.)

Therefore how many of the legends of Villa Jovis are true or not is uncertain — but, for obvious reasons, it has fascinated later authors and artists ever since Tiberius’ death. Today, streams of tourists still climb the steep slope to gaze at its ruins, peer over the cliff-top (from where errant subjects were hurled, the legend has it), and wonder just how the afternoons passed, when all the world’s depravities were gathered under one roof.

Ruins of Villa Jovis (photograph by Satoshi Nakagawa)

THE THESSALONIKI BROTHEL

Thessaloniki, Greece

Almost all of our sources on love and sex in the ancient world have one thing in common: they were produced by men, and for men. Recovering women’s perspectives is exceedingly difficult, and an ongoing challenge for scholars. For “respectable” women, the great Athenian leader Pericles says in his Funeral Speech, the greatest glory is simply to disappear: “not to be talked about for good or for evil among men” (Thucydides, 2.45).

Yet Pericles himself is said to have fallen in love with one of the most remarkable and visible women we know of from the ancient world — the brilliant courtesan Aspasia:

Aspasia, as some say, was held in high favour by Pericles because of her rare political wisdom. Socrates sometimes came to see her with his disciples, and his intimate friends brought their wives to her to hear her discourse, although she presided over a business that was anything but honest or even reputable, since she kept a house of young courtesans. […] Twice a day, as they say, on going out and on coming in from the market-place, Pericles would salute her with a loving kiss. (Plutarch, Pericles, 24).

Fresco from a brothel in Pompeii (via Wikimedia)

Ancient Greek, it’s frequently said, has many more words for “love” than English. That’s true. It also has many more words for “prostitute.” Few — very, very few — of these prostitutes had the independence and security of Aspasia, or other educated and prosperous hetaerae.

At the other end of the scale were the pornae (from whom we get the word “pornography”). It’s a word for which any English translation must be both dismissive and degrading; “street-walker” or “bus-station whore.” Their lives were not bright things. Often slaves, rarely with any control or agency of their own, they were frequently confined in brothels.

Ancient Greek erotic art (via Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

A number of ancient brothels have been excavated – most famously in Pompeii. In Thessaloniki, a brothel dating from the second century BC was discovered in 1997 attached to a public bathhouse, in the ancient agora, or marketplace of the city. This was an exceedingly well-equipped house of debauchery: on the ground floor was an elaborate dining room and a direct link to the bath-house — while above, there was a warren of tiny rooms.

Most eye-opening were the artifacts: a large phallus-shaped alabaster vase, jars with phallic mouths, even parts of an ingenious hand-cranked sexual aid (briefly displayed in a side-room of the local museum, but now gathering dust in storage). It’s one of the few windows we have into the everyday sexual life of an ancient city.

SEXUAL CURSE TABLETS

Agios Tychon, Cyprus

Curses of all kinds were big business, across the ancient world. Threatening tomb-curses were a feature of many Egyptian burials, and they lingered to trouble overzealous Victorian archaeologists. For example: “Anyone who does anything bad to my tomb, then the crocodile, hippopotamus, and lion will eat him.”

Collected together, they make for fearsome reading: “I shall seize his neck like that of a goose.” “His face shall be spat at.” “A donkey shall violate him, a donkey shall violate his wife.” “He shall be cooked together with the condemned.”

Greeks and Romans would scratch these messages to the gods onto sheets of lead now known as curse-tablets, and promise rewards if the gods did their vengeful bidding: “may [the thief] neither piss, nor shit, nor speak, nor sleep, nor stay awake, nor have well-being or health, unless he bring what he has stolen to the temple of Mercury.”

An ancient Roman curse tablet found in London (via British Museum)

Many of these curses were explicitly erotic in nature, impotence and sexual misery wished on many a target. Ovid, having disappointed a lover, did not hesitate to blame a witch: “Perchance ‘twas magic that turned me into ice.”

Love-magic can be traced all the way back to Homer’s Odyssey, where Calypso weaves spells to make Odysseus forget his home. There are, as John Gager notes in Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World, “spells to curse rivals, to divorce or separate couples, to cause a downturn in a pimp’s business, and to attract a lover.” Gager points out the vivid urgency of these tablets: “Bring her thigh close to his, her genitals close to his in unending intercourse for all the time of her life.”

Amathus, Cyprus (photograph by Shonagon/Wikimedia)

In 2008, while excavating the city of Amathus, on the south coast of Cyprus, archaeologists found a curse which went straight to the point: “May your penis hurt when you make love.”

This was inscribed once again on a lead tablet, in Greek. Perhaps most surprising was the date of this tablet — the seventh century AD, hundreds of years after the sack of Rome, and the spread of Christianity across the Mediterranean world. While many of the old pagan beliefs had disappeared or been suppressed by this period, it is clear that people’s love of — and need for — sex-curses had not gone anywhere.

THE TEMPLES OF KHAJURAHO

Chhatarpur, India

Temple carvings at Khajuraho (via Wikimedia)

No guide to sexuality and the past could be complete without Khajuraho. In Madhya Pradesh, far distant from the old imperial cities of India, are a remarkable group of temples, eye-popping in their erotic intensity. They were built, it is believed, between 950 AD and 1150 AD. Women, men, and questionable beings embrace athletically and relentlessly in their carvings.

Khajuraho is sometimes said to have been “discovered” by British colonial officers during the 19th century — though as the temples were well-known to Indians for centuries beforehand, such accounts are problematic. Nevertheless, Khajuraho’s fame in the Western world was sparked in great part by the 1860s account of Alexander Cunningham.

Cunningham, while fully aware that he should seriously disapprove, was entirely enraptured. He described “a small village of 162 houses, containing rather less than 1,000 inhabitants,” overshadowed by gigantic sacred sites: “All of these [sculptures] are highly indecent, and most of them are disgustingly obscene. […] The general effect of this gorgeous luxury of embellishment is extremely pleasing.” In his published illustrations, however, the faces of the temples — alive with carvings in reality — are blank, subdued, and nonthreatening.

The temples of Khajuraho (via Wikimedia)

Despite its remoteness, Khajuraho has become one of the most popular attractions in India. Scholars still puzzle over the purpose of its erotic carvings — which comprise only around 10% of the total number of sculptures: were they a sex-education manual for cloistered young men, a Tantric text, or something very different? And when exactly — was it at the point of Cunningham’s arrival? — was it that Khajuraho became “obscene,” part of the perverted past?

GABINETTO SEGRETO

Naples, Italy

Mosaic of a satyr and a nymph from Pompeii’s House of the Faun (via Museo Archeologico Nazionale)

Ancient sexuality has a long history of making people uncomfortable. Explaining that 180-foot-long, gold-plated Alexandrian phallus was not a task which many scholars fancied in Victorian London, for instance. The 19th century was one of the great periods of rediscovery of the classical past: from sculpture, to poetry, to archaeology, to history, knowledge became sharper and more fascinating. But it was also one of the greatest periods of censorship; antiquity was systematically mutilated to fit with contemporary Christian morality.

The “Venus Kallipygos” — or “Venus with the lovely ass” — from the Gabinetto Segreto (via Wikimedia)

The forthright lewdness of many ancient authors was hacked down into a school-room whine: “I have carefully omitted,” wrote one editor of Aristophanes, “every verse or expression which could shock the delicacy of the most fastidious reader.” Even Gibbon, known for his appetites, put all of his most salacious footnotes in the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in Latin — so much so that one historian remarked that Gibbon’s sex life was mostly lived out through his footnotes.

But one of the most notorious cases of censorship came when Pompeii began to be systematically excavated. There were stone phalluses by the dozen, erotic mosaics, an entire ancient brothel, phallic wind-chimes, and a particularly detailed carving of a satyr having sex with a female goat, her cloven feet pressed up against his chest as she gazes back at him, with an expression rarely found on the face of a farm-animal.

The Gabinetto Segreto’s goat (via Wikimedia)

King Francis I of Naples visited Pompeii in 1819 with his wife and young daughter. He was given the complete tour, and promptly ordered the censorship of an entire ancient city’s erotic life. All vaguely sexual objects were whisked away from public view. Metal shutters were installed over frescoes. Access was restricted to scholars or enterprising young men, prepared to pay the going rate to bribe the guards.

Predictably, this censorship cemented the fame of Pompeii’s secret history, and the forbidden collection became a semi-obligatory stop on young aristocrats’ Grand Tours. Remarkably, the Gabinetto Segreto, as it was known, remained hidden throughout the 20th century, and was only opened to the public in 2000. Today, at last fully acknowledged, it remains Pompeii’s best guilty pleasure.

BABYLON

Hilla, Iraq

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon by Maerten van Heemskerck (1498-1574) (via Wikimedia)

“The perverted past” is always at least half-invented: later cultures look back, and judge, and condemn. Nowhere is this truer than in Babylon — city of whispered sin, and ever-taller tales.

One of the oldest and most storied cities on earth, Babylon was first settled around 4,000 years ago. From a small city-state, it grew to a seat of empire, wealth, and power. Nebuchadnezzar II turned Babylon into perhaps the most astonishing city on earth, its walls lined with a hundred gates, its Hanging Gardens one of the wonders of the ancient world (though their historical form is disputed). Tales of Babylon — and Babylonian depravities — spread across the world:

The Babylonians have one most shameful custom. Every woman born in the country must once in her life go and sit down in the precinct of Venus, and there consort with a stranger. Many of the wealthier sort, who are too proud to mix with the others, drive in covered carriages to the precinct, followed by a goodly train of attendants, and there take their station. But the larger number seat themselves within the holy enclosure with wreaths of string about their heads […] and the strangers pass along them to make their choice.

A woman who has once taken her seat is not allowed to return home till one of the strangers throws a silver coin into her lap, and takes her with him beyond the holy ground. When he throws the coin he says these words: “The goddess Mylitta prosper thee.” (Venus is called Mylitta by the Assyrians.) The silver coin may be of any size; it cannot be refused, for that is forbidden by the law, since once thrown it is sacred. The woman goes with the first man who throws her money, and rejects no one. When she has gone with him, and so satisfied the goddess, she returns home, and from that time forth no gift however great will prevail with her. Such of the women as are tall and beautiful are soon released, but others who are ugly have to stay a long time before they can fulfill the law. Some have waited three or four years in the precinct. (Herodotus, Histories, 1.199, trans. Rawlinson).

The site of Babylon, viewed from Saddam Hussein’s summer palace (via Wikimedia)

In October of 331 BCE, Babylon fell to Alexander the Great, and Alexander would die there, in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, eight years later. Babylon’s greatness was soon a memory — its inhabitants scattered, its temples devastated in the wars which followed. The city swiftly passed into legend. The “whore of Babylon,” an allegory of the Roman Empire, marched through the Book of Revelation: ”Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth.” Herodotus’ narrative of the sex temples of Babylon was taken up, unquestioned, by generations of scholars — yet most now agree that it was, at least in great part, fictional; a tale of the “perverted other,” told to raise eyebrows and pulses amongst his Greek readers.

Each generation reinvents the sexual histories of the past, to suit its own desires. From Victorian censorship, to contemporary fascination with “the perverted past,” the history of many of these places is the history of our own shifting and often uncomfortable relationship with ancient sexuality. They show us a different world — they demand we look it straight in the eye, and acknowledge what it is: as potently erotic as it is profoundly alien.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook