The Essential Guide To Secret Museums

Prepare to marvel at these hidden museums considered unfit for public viewing.

From a Soviet weapons cache in an unrecognized country to a gruesome display of human anatomy on restricted display in a forbidden gallery, this guide will take you through some of the world’s least-known museums and collections. While a tour of the Louvre or the Smithsonian would entail buying a ticket, waiting in line, then marveling at famous attractions alongside hordes of other camera-flashing tourists, a visit to one of these museums will offer an experience much more clandestine. Below are seven of the world’s most notorious and secretive museums.

1. The Black Museum

LONDON, ENGLAND

Our tour begins in London.

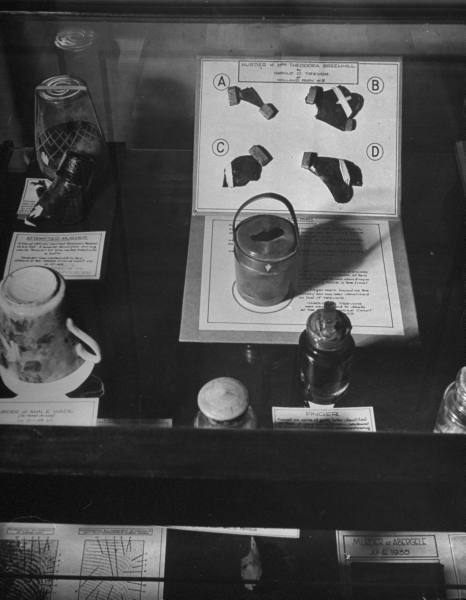

Officially known as “The Crime Museum of Scotland Yard,” this extensive collection of criminal and judicial memorabilia is better known as the Black Museum.

Established unofficially in 1874, the Black Museum started off as repository for property confiscated from prisoners. Taking advantage of the 1869 Prisoners’ Property Act, an inspector named Neame had intended the small exhibition of murder weapons to serve an educational purpose for police officers — giving practical instruction on the detection and prevention of crime.

The collection was housed at Scotland Yard, under the watchful eye of London’s Metropolitan Police Service. It grew fast and by the next year was granted official museum status by the government, with a permanent guard on duty. Over the following years the museum saw a steady increase in visitors — many of them high-ranking commissioners and captains of police. The expanded collection by then featured tools used in famous crimes, as well as a range of decommissioned execution equipment.

In 1890, the Black Museum followed the Metropolitan Police Office as it moved to the newly built Thames Embankment. There it stayed for almost a century, slowly expanding. Visiting rights remained notoriously hard to acquire. Then, almost a century later, it was moved to Room 101 at New Scotland Yard.

The grisly contents of the Black Museum are arranged across two areas — the first a replica of the original museum, housing period weapons and execution equipment: shotguns disguised as umbrellas, hangman’s nooses, and letters allegedly penned by Jack the Ripper. The other half of the museum is focused on 20th century crimes. Exhibitions include the ricin pellet used in 1978 to kill Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov, as well as a fake diamond from the Millennium Dome heist, and even the stove that serial killer Dennis Nilsen used to boil the heads of his victims.

To this day, the Black Museum remains closed to the public. While officers from any of the country’s police forces are welcome to visit by prior arrangement, the infamy of the Black Museum makes for a rather long waiting list. In recent years there has been a movement in favor of open entry at the museum (not least for the money-making potential it would bring to Scotland Yard), but the idea is yet to be backed by official approval.

2. Gabinetto Segreto

NAPLES, ITALY

Moving from the gruesome to the gratuitous, our next museum takes us to Italy.

One of Europe’s most notorious secret museums, the Gabinetto Segreto (or “Secret Cabinet”), represents a sordid collection of erotica excavated from the ashes of Pompeii.

The relics were gathered in the late 18th century, under the guidance of Charles III of Spain. When Naples changed hands the saucy sculptures and titillating frescoes were relocated to the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

The ancient Romans were far more liberal with their sexual imagery than could be said for Western Europeans in the 19th century. As a result the collection from Pompeii–featuring stone penises, erotic mosaics, statuettes depicting acts of bestiality, and more nudes than you could shake a phallus at–did not receive a warm welcome in the “civilized world.”

King Francis I of Spain visited the National Archaeological Museum of Naples in 1819 with his wife and young daughter. The king was so appalled by what he saw that he ordered all erotic material to be locked in a secret cabinet: the Gabinetto Segreto.

But of course, scandal brings intrigue; and soon enough, wealthy European gentlemen were queuing up to bribe the museum staff, eager for a glimpse at these naughty murals, paintings, and statuettes. By 1849, the collection was bricked off altogether, its very existence becoming shrouded in mystery for over a century.

It wasn’t until 2000 that the cabinet was finally opened up to the public, backed by popular demand — and in 2005 it was moved to its own separate gallery. Visitors to the Naples museum can now view the murals depicting illicit trysts between gods, phallic charms and wind chimes, countless nude figures and, perhaps the most notorious item: a detailed sculpture of a mischievous satyr, locked in intercourse with a female goat.

3. CIA Museum

LANGLEY, VIRGINIA

Meanwhile, on the other side of the planet we find a closed museum curated by America’s most notoriously secretive government organization: the CIA Museum in Langley, Virginia.

According to the official website, “the CIA Museum supports the Agency’s operational, recruitment and training missions and helps visitors better understand CIA and its contributions to national security.” This impressive collection of artifacts numbers over 3,500 individual items, with recent additions including an Al-Qaida Training Manual retrieved from Afghanistan in 2001, as well as Osama bin Laden’s own AK-47.

The items on display at the CIA Museum cover weaponry, uniforms, and equipment associated with the CIA and its staff, as well as similar effects pertaining to other intelligence organizations the world over. The museum also features a wealth of high-tech spy gadgets developed for use by these organizations, including pigeon spy cameras.

At present the CIA Museum maintains three permanent exhibitions. The North Gallery was dedicated in 2002 on the 60th anniversary of the OSS — or “Office of Strategic Services,” a precursor to the CIA itself. The exhibition contains personal effects of founder Major General William J. Donovan, in addition to intelligence equipment of the time; ranging from a German “Enigma” machine to the OSS’s own inventions.

The Cold War Gallery houses objects of that era hailing from the United States, East Germany, and the former Soviet Union. Opened in collaboration with private collector Keith Melton, this is just a sliver of the 7,000 items that make up the world’s largest private collection of intelligence equipment.

The third gallery is located in the Fine Arts Exhibit Hall, and goes under the title of “Analysis Informing American Policy.” This particular installation celebrates the 1952 creation of the Directorate of Intelligence.

According to the official website, all items at the CIA Museum are “held in trust” for the American people; the museum does not, however, open its doors to visitors. Instead it organizes frequent public exhibitions, usually conducted in association with the Presidential Libraries or other museum institutions. These displays are targeted at promoting better understanding of the craft and history of the intelligence services, and their role in what the museum dubs, “the broader American experience.”

4. Shanghai Museum of Propaganda Posters

SHANGHAI, CHINA

The Shanghai Museum of Propaganda Posters started out as a small private collection before growing to become an extensive museum incorporating more than 5,000 individual prints. It is, however, famously hard to find.

Located in the basement of an apartment block in a suburb of Shanghai, a few scant signs will direct you to the museum if you know where to look.

The collection focuses primarily on the first 30 years of the People’s Republic of China, with Mao Zedong’s rise to power followed by China’s “Great Leap Forward.” Lithographic prints align Mao’s face with those of other key communist figures: Marx and Engels, Lenin and Stalin. Others show scenes of battle — such as one particularly striking pop art visual in which the combined forces of China and North Korea — represented by strong, handsome soldiers — disarm a grotesquely disfigured American G.I.

Other posters show signs of peace and prosperity: the proletariats of a socialist utopia stand tall and proud, fists in the air, or are pictured with a well-read copy of Mao’s Little Red Book.

The majority of pieces on display at the Shanghai Museum of Propaganda Posters come with English translations:

“Help North Korea to fight America, rescue neighbour and self-salvation!” reads one.

Another proclaims: “Long live the great Marxism, Leninism and Maoism,” while a third reads, “Catch up and exceed UK in 15 years.”

An image of olive-skinned arms plunging a sword through beasts dressed in the flags of Britain and the US, is captioned: “All the Arab people unite, stop the war of aggression.”

Aside from the main collection of propaganda posters, other exhibitions in the museum include examples of the calligraphic denouncement posters, or “big character reports,” which ordinary citizens were permitted to display in the post-revolution years; as well as a feature on Shanghai pin-up girls, as popularized by advertising posters in the 1930s.

5. Siriraj Medical Museum

BANGKOK, THAILAND

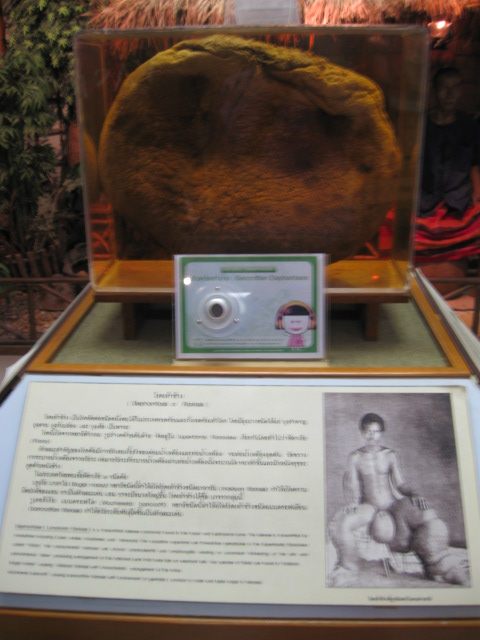

Our next museum takes us to Thailand, for a graphic exploration of the inner-workings of the human body.

This particularly grotesque collection is housed within Bangkok’s Siriraj Hospital. As the oldest and most prestigious hospital in the country, the Siriraj cares for the health of the Thai royal family. King Rama IX spent the last several years of his life in the hospital until his death in October of 2016.

Established in 1886, the reputation of the Siriraj Hospital attracts students and scholars from across Southeast Asia; and numerous museum-style exhibitions have been established on-site. The Siriraj Medical Museum, also known as the Museum of Death, is divided into sections covering prehistory, anatomy, parasitology, forensics, pathology, and the history of Thai medicine.

While each of these exhibits contains its fair share of curiosities, it is the anatomy section which is most likely to turn heads (and stomachs.) Displays include jarred fetuses, parasitic worms, the deformed scrotum of a man suffering from elephantiasis, a dissected nervous system, and the skeleton of the museum’s own founder, bequeathed to the collection in his will.

Meanwhile, the forensics exhibition features a selection of well-preserved human corpses–many intended to demonstrate the anatomical effects of different modes of death. You’ll find the corpses of drowned and strangulated men, in addition to the mummified remains of one of Thailand’s most notorious serial killers: the cannibalistic child catcher, Si Ouey Sae Urng.

Throwing a new shadow of horror across the collection, there has been some debate in recent years concerning the source of the corpses at the Siriraj Medical Museum. Officially, most of the bodies are sourced from Japan, bought for educational purposes. However, new information suggests that the dismembered bodies may once have belonged to political prisoners in China. Exposé pieces from local websites have been removed by the government, and it’s possible that fear of a scandal has contributed to the limited information made available about the museum.

Whatever the truth is, the Siriraj Medical Museum remains one of Bangkok’s most bizarrely fascinating attractions; and, while the museum is open to the public it’s generally overlooked by travel guides, which along with its obscure location and secretive collection earns it a place on this list.

6. Musee D’Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouviere

PARIS, FRANCE

Our next location is another museum of anatomy. However, while some of our more adventurous readers may have found their way into Bangkok’s Medical Museum, we’re willing to bet you haven’t seen this one.

The Musée d’Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière can be found on the eighth floor of the Faculty of Medicine, at René Descartes University. The collection is quite unique–an assortment of more than 5,800 items, which are guarded under lock and key.

Inside the museum’s halls are anatomical figures painstakingly formed from wax, animal specimens, skulls, skeletons, and a large collection of preserved brain specimens. The latter display includes the brain of Paul Broca: the very anatomist who started the collection and lent his name to a region of the cerebral cortex responsible for governing speech.

The collection was begun in 1794 by the revered professor of anatomy, Honoré Fragonard (you can still see some of his anatomical oddities today, at the nearby Musée Fragonard in Maisons-Alfort). What started as a single cabinet at the Faculty of Medicine grew to incorporate those relics of science that had survived the sacking of academic institutions inspired during the French Revolution. It also attracted the fresh work of rising stars in the fields of science and medicine.

In 1844, the cabinet became a museum. Mathieu Orfila, dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris, was inspired by what he saw on a trip to London’s Hunterian Museum; in 1847, the blossoming museum was named the “Musée Orfila” in his honor. By 1881, it contained almost 4,500 specimens.

Sadly, the museum did not fare well with the dawn of the 20th century. Wax models created by master surgeon Laumonier were burned for light, and the extensive catalogue was in time reduced to mere hundreds of items. It wasn’t until 1947 that any attempt was made to restore the collection. Professor André Delmas joined the dwindling museum with the lymphatic models of Professor Henri Rouvière, formerly on display as part of the “Musée Rouvière.” He combined his own name with those of Rouvière and the museum’s founder, to form the new Musée d’Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouviere.

Since then, the museum has become something of a holy grail amongst students of anatomy. The collection now features such diverse installations as Broca’s casts of bird, mammal, and human brains; the skulls and death masks of 19th century criminals and the mentally ill; displays of brain malformations in rat specimens; detailed models of the human lymph systems, liver, kidneys, and trachea; as well as the famous Spitzner collection: a macabre series of 19th century anatomical wax models.

Despite snowballing interesting in the collection, the museum remains off-limits to both tourists and researchers alike.

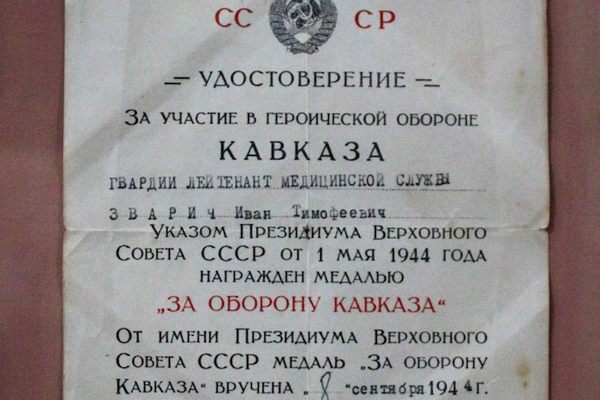

7. Bendery Military Museum

BENDER, MOLDOVA

The last museum on our list takes us to Eastern Europe, in one of the strangest places you’ve probably never heard of. The Bendery Military Museum with its extensive collection of militaria is tucked away in consecutive carriages of an old Soviet steam train; parked beside a disused station, in a small town, in a country that, according to the rest of the world, doesn’t exist.

Welcome to Transnistria: a breakaway Soviet socialist republic on the border between Moldova and Ukraine, formed after the 1991 Fall of the Soviet Union. While Moldova joined the West, the Transnistrian leadership were hesitant to break ties with the former USSR — and so this micro-nation of just 2.3 million inhabitants staked their independence.

Moldova did attempt to reclaim the territory between 1990 and 1992, a conflict that would become known as the War of Transnistria. However, the region had served as one of the main arms manufacturers for the Soviet Union, and so despite its diminutive size, Transnistria had one of the largest stockpiles of weaponry in Eastern Europe. The territory remains fiercely independent, and yet universally unrecognized, to this day.

The military museum in question is located in a town called Bendery, right on the border with Moldova. Within, visitors are treated to a rare collection of military artifacts pertaining to the Ottoman occupation of the area, Bendery’s role in both WWI and WWII, and of course the later War of Transnistria. Exhibits include a large collection of weapons, moth-eaten uniforms, and cabinet after cabinet full of maps, certificates, and other documents — many of them sent from Moscow, and bearing Stalin’s own stamp of approval.

Each one of the museum carriages is presided over by a cheerful babushka, who will gladly talk you through each one of the rare and peculiar exhibits in Russian. Not a single word in the museum appears in Latin script, let alone in English. The Bendery Military Museum is free to enter and relatively easy to find (once you’ve crossed the heavily militarized border, of course). However, the language barrier means that the information contained within this train will mostly remain a secret even from the handful of non-Russian tourists who actually make it this far.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook