Every Major Trope of the American West Can Be Found on One Ranch

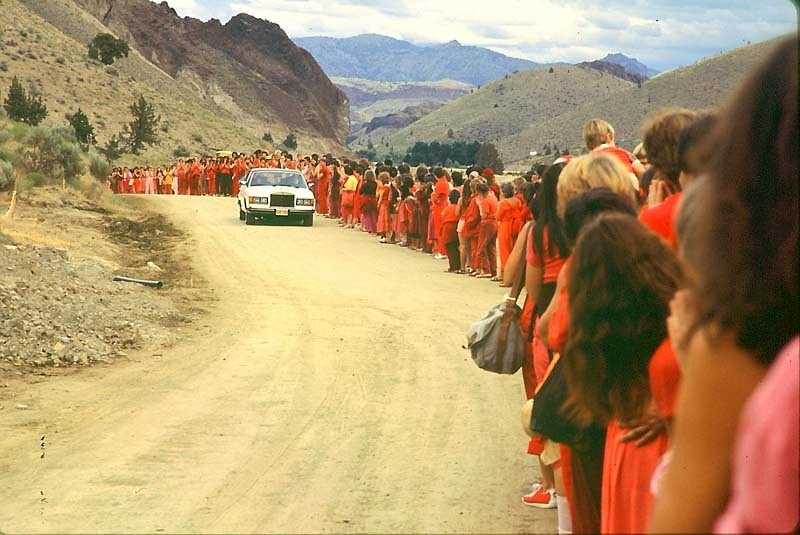

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh in his Rolls Royce, driving by his devotees in the summer of 1982. (Photo: © 2003 Samvado Gunnar Kossatz/WikiCommons)

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh in his Rolls Royce, driving by his devotees in the summer of 1982. (Photo: © 2003 Samvado Gunnar Kossatz/WikiCommons)

Last fall, the Washington Family Ranch found itself unable to go forward with an expansion to its luxe compound. Already, it had water slides and club houses, zip lines and go-carts and, like most nondenominational ministries, lots of multimedia equipment. The ranch is run by Young Life, an evangelical Christian organization based in Colorado Springs that works with impoverished or at-risk teens. The Washington Family Ranch, located in the sparsely populated high desert of north central Oregon, is the 74-year-old ministry’s biggest camp of all.

Young Life has been pushing to expand the ranch since the late 1990s, after they were deeded the ranch by a Montana billionaire looking to unload an otherwise barren and unprofitable piece of land. But Oregon State has continually placed restrictions on these plans, and citizens of the tiny neighboring hamlet of Antelope are wary, too.

That’s because this particular ranch has been site of tension, in one way or another, for the past 120 years. During that time, the land has been the stage of a fatal shoot-out between settlers and Native Americans, and also a movie set for the 1975 John Wayne vehicle “Rooster Cogburn.” More notoriously, it’s been the site of the New Age “city” Rajneeshpuram, home to thousands of ecstatic, red-clad followers of the guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. In 1984, a few of these disciples ended up carrying out the largest domestic bioterrorism attack in U.S. history.

The sign for Rajneesh, in 1985. (Photo: Ted Quackenbush/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The sign for Rajneesh, in 1985. (Photo: Ted Quackenbush/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The property was first settled as the Muddy Ranch. “The Big Muddy,” as it is affectionately called, sprawls out over 64,000 acres of dusty hills, covered by sage and juniper and a wandering steer here and there. Kentucky settler Howard Maupin founded neighboring Antelope in the 1860s where he worked as postmaster and operated the stage coach.

Shortly after he arrived, the U.S. Military signed a treaty with the Paiute Indians which pushed them out of the mountains surrounding Antelope, and into reservations further west. When Paiutes started defecting from the reservation not long later, finding the treaties unfair, Chief Paulina was among those who set out to reclaim their territory in the Blue Mountains.

One night, Maupin, reinforced by a posse, shot and killed Chief Paulina just outside of Antelope, and in some accounts is said to have tacked his scalp above the stage coach as a warning. When a Paiute medicine man found out about the murder, he came to Antelope and put a curse on Maupin “and his land forever.”

Over the following years, the ranch served as a cattle and sheep concern, and eventually, a new stop on the stage coach line. Then, for a good deal of the mid-20th century, the Muddy Ranch was dormant as American rangeland practices shrunk to outsourcing and Big Ag.

In the 1970s, Katharine Hepburn and John Wayne found themselves tromping around the Muddy Ranch filming “Rooster Cogburn,” a tepid sequel to “True Grit,” the story of a hard-drinking, disgraced U.S. Marshall questing to get his badge back, accompanied by his “spinster” sidekick seeking her father’s revenge. In that great American tradition of re-enacting the history of the West, Hepburn and Wayne took the law into their own hands, battling bandits and road warriors from the fortress of a homestead.

Later, when the followers of the Bhagwan Rajneesh bought the property and stories began to spread of tensions between locals, People predicted “a showdown stranger than any the Duke envisioned.”

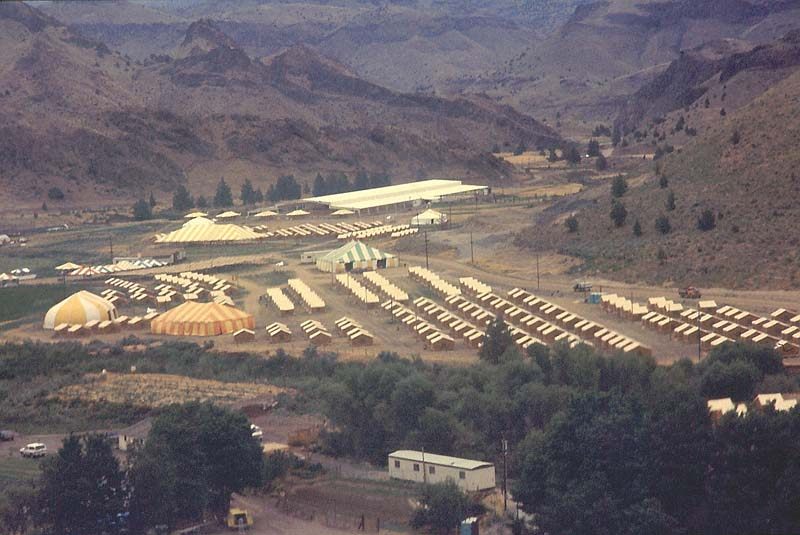

Tents at Rajneeshpuramin 1982. (Photo: © 2003 Samvado Gunnar Kossatz/WikiCommons)

This September is the 30th anniversary of the dissipation of Rajneeshpuram, the utopian city established on the Muddy Ranch. For a time in 1984, Rajneeshpuram was not only the fastest growing city in Oregon, but potentially the fastest growing city in America, according to the Chicago Tribune. At its peak, there were between 2,000 and 3,000 permanent residents, though it was built to house 6,000, and around gatherings and festivals the population reportedly rose into the tens of thousands.

But just a year later, this intentional community met its dramatic end when its two most powerful leaders, the Bhagwan himself and his fearsome spokeswoman, were charged respectively with immigration fraud, conspiracy, attempted murder, and organizing the single largest domestic bioterrorism attack in America.

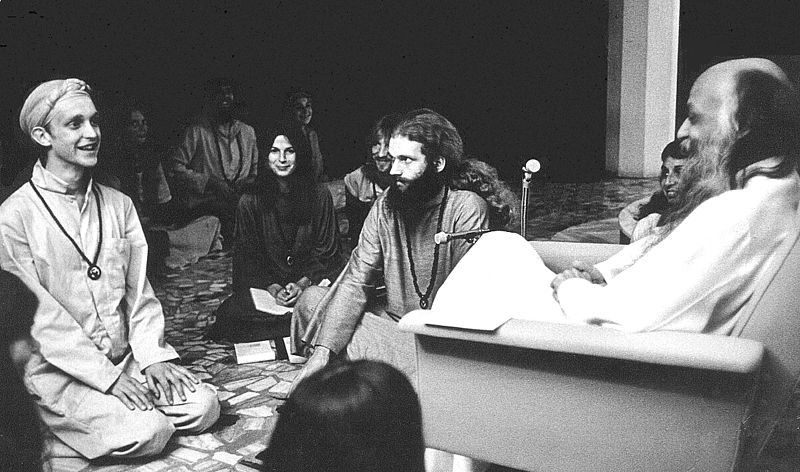

The Bhagwan and his disciples arrived in Oregon during the summer of 1981, having already developed a strong following in his ashram in Pune, India. Many Westerners were drawn to his philosophy, which mixed Buddhism and continental thought, and encouraged the practice of free love and meditation. Olof Soderback was among the early followers in Pune and remembers fondly “gardening there for a year” and meeting his wife.

The 2,000 or so disciples immediately began building permanent housing—small outbuildings and tents, and then more lavish quarters for the “enlightened one” himself. They got to cultivating farmland, and setting up security details at the front of the ranch near the main road. There were daily devotional gatherings, meditation sessions, and “encountering sessions,” where the philosophy of free love was often practiced. And the Bhagwan began collecting Rolls Royces, in which he’d be chauffeured daily through the gauntlet of his devotees.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and disciples in Poona (present-day Pune), India, in 1977. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and disciples in Poona (present-day Pune), India, in 1977. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Within three years, they had become incorporated as a municipality: Rajneespuram. At the time, the Chicago Tribune ran a profile on the community, describing a “technologically impressive, ecologically sound 2,000-acre city with an airport, shopping center, hotel, disco, restaurants, a blackjack casino, transportation system, newly built dam and lake and near self-sufficient agricultural production” staffed by the hardworking, red-clad devotees who lived in simple cabins and A-frame tents. The Rajneesh also bought up, over time, one-fifth of the property in Antelope, which included in its sweep a general store and café that they reintroduced as an all-vegetarian spot called Zorba and the Buddha.

Though Soderback didn’t live on the compound in Oregon, he did visit once and remembers staying with his wife in A-frame tents built on wooden platforms. “This was much more a rustic pioneering camp [than the ashram in Pune],” Soderback says, “where everybody was just working, working, working. Work was the meditation.”

Needless to say, the residents of Antelope weren’t happy about this massive influx of disciples. And the state of Oregon began to level complaints and lawsuits against Rajneeshpuram’s unsanctioned use of land and lack of building permits. Plus, by then, Rajneeshpuram had its own police force that, in addition to patrolling the compound, also patrolled the streets of Antelope armed with Uzi submachine guns.

A 1985 photo of Krishnamurti Lake, along the road to Rajneeshpuram, with a dedication stone to Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. (Photo: Ted Quackenbush/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

A 1985 photo of Krishnamurti Lake, along the road to Rajneeshpuram, with a dedication stone to Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. (Photo: Ted Quackenbush/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Many of the more aggressive occupation efforts were allegedly fueled by the Bhagwan’s mystic spokeswoman, Ma Anand Sheela, who by then had been given control of much of the activity of Rajneeshpuram. Soderback attributes the expansionism of Rajneeshpuram to “Sheela’s great admiration for American business and American money,” adding that he was ousted shortly after arriving for his visit. “If you didn’t behave exactly according to her rules, you were out.”

In an attempt to gain voting power to have sway in decisions about land use in Wasco County, where Rajneeshpuram was located, Sheela and other higher-ups arranged to bus in thousands of homeless people to vote. They also carried out a mass salmonella poisoning of eateries in the heart of the county seat. Rajneeshee delegates surreptitiously drizzled infected liquid into the Taco Time salsa bar and other restaurants, a strike which left 751 people infected and successfully stifled voter turn-out on election day. Eventually, these acts would lead to the dissipation of Rajneeshpuram.

Soderback remembers that the last time he saw the Bhagwan, he “was in the Rolls Royce, and there was a plane overhead that was pouring out rose petals that were just falling down on his car. But at the same time the rose petals were falling, we walked out of there, never to return.”

Eventually, Sheela and her henchmen were charged with a variety of crimes, including attempted murder. The Bhagwan was charged with immigration fraud (from arranged marriages) and conspiracy, but fled to India after being let out on bail. He settled into a quiet life with his disciples there, dying of a heart attack just five years later.

Air Rajneesh in 1987, which was used to transport passengers and cargo. (Photo: RuthAS/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In an ironic twist, Young Life began to develop the same piece of land into their own compound in 1991, a $300 million dollar “Christian ranch” where inner-city kids were carted to lavish water parks and rural splendor for summer fun and worship. When they arrived, it was still what the New York Times called “the first ever New Age ghost town.”

Young Life got the property through the Montana billionaire Dennis Washington, a mining and construction magnate listed in Forbes as the 87th richest person in America. He had purchased the Muddy Ranch in 1991 for almost half the price the Rajneesh bought it for, and then he sat on it unsure of what to do because of all the land use restrictions. For a while, he and then-Governor John Kitzhaber talked about turning it into a state park, and then, maybe, a youth correctional center.

When Young Life got the land it seemed, at first, like it was going to be a technical challenge to engineer their dream ranch on the land. But they had a few lucky breaks. The Statesman Journal reported that the camp’s plans to build a man-made lake were stymied by the fact that the arid environment would cause evaporation at 10,000 gallons per day. But then the group happened across a natural spring below the new swimming pool that pumped exactly 10,000 gallons a day. Moreover, when the camp’s sports field needed a large quantity of sand to prevent mud, someone tooling around on the property found a huge sand deposit.

And finally, when they couldn’t decide what to do with the Bhagwan’s lavish former quarters, “a 1997 range fire decided matters,” wrote the Statesman Journal. “A finger of the fire raced down the ridge and torched the residence, the only one of 300 Rajneeshpuram buildings to burn.”

In the same article, a Young Life camp leader at the Washington Family Ranch marvels that “this place is a gift,” and a camper, having just completed the ropes course, professes that “God’s grace definitely changes lives at Washington Family Ranch.”

A plaque at the post office in Antelope, Oregon. (Photo: Travis L/ WikiCommons CC-BY-3.0)

A plaque at the post office in Antelope, Oregon. (Photo: Travis L/ WikiCommons CC-BY-3.0)

But miracles and blessings aside, Young Life had to push for several years for clearance to develop 40 more acres of land. While the State Legislature did eventually pass a bill to rezone the land, another land management agency stepped in and set up rules that limited capacity and sewer system connectivity.

The latest concerns drift more to the delicate ecology of the high desert, the preservation of indigenous artifacts, and not wanting to set “a precedent for circumventing the land-use process by making accommodations to special interests,” says Representative Mitch Greenlick. Many of the 50 or so Antelope locals are ranchers, after all, whose livelihoods depend upon that sweeping rangeland.

It would just be a run-of-the-mill land-use squabble, so typical of the rural American west, were it not for the fact that many of the current residents still remember having been run out of town or poisoned with salmonella by Rajneeshees; or that John Wayne had blessed the land with his cowboy boots; or that the Pauites cursed it with their blood.

So while the expansion plans of Young Life may be still developing, the spirit of the Muddy Ranch continues to live on, against threats of drought and scarcity, cleaving to enlightenment.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook