A Fond Farewell to Britain’s Prefab WWII Bungalows

Built in a time of crisis and intended to be temporary, they have created long-lasting communities.

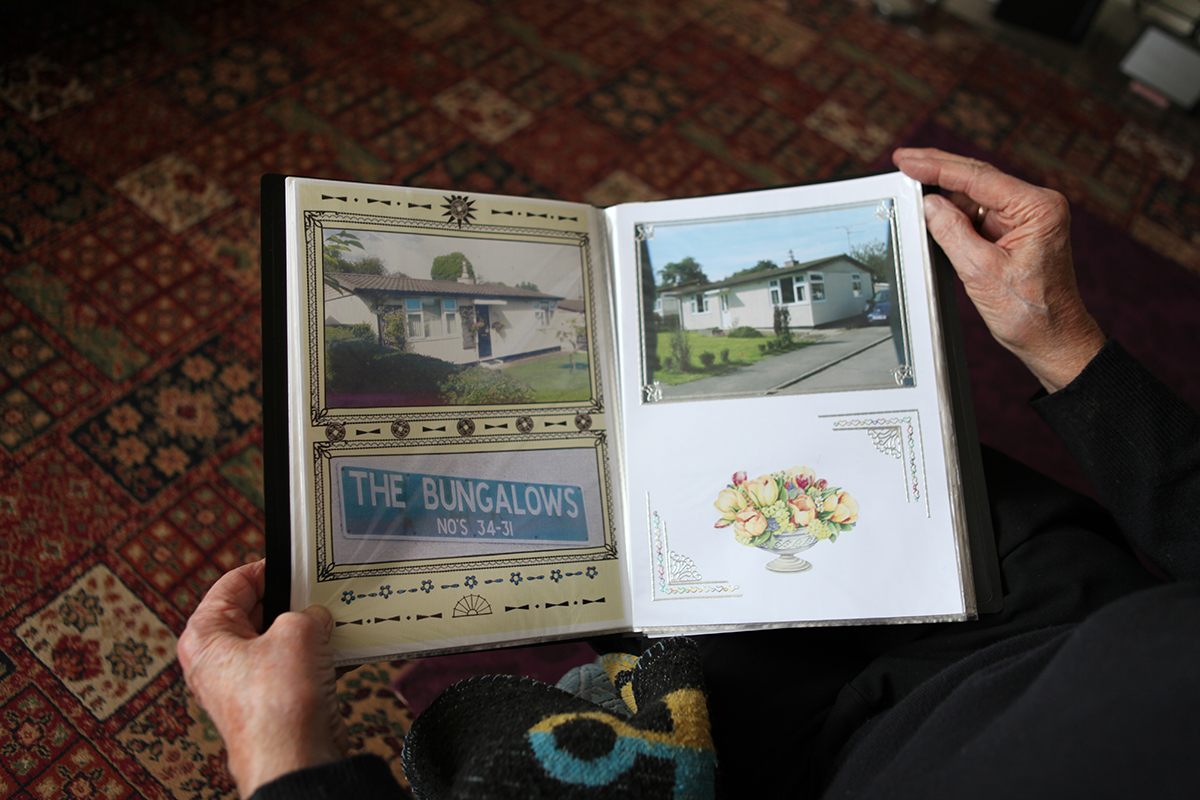

For decades, residents of the Excalibur Estate, London’s last community of post-World War II, prefabricated houses, have been fighting against property developers and hostile local authorities to save their lovely bungalows from demolition.

This fight has proven to be in vain, as, driven by rising land values, Lewisham Council started to pull them down in 2014 and “regenerate” the estate, destroying a unique architectural and social entity. Standing on a land—in Catford, southeast London—now worth a fortune, more than one hundred bungalows are still lived in and cherished. Before they all go, here is a look at the last prefabs standing—and their residents.

Britain was bombed heavily during the war. The Blitz and the continuous bombing of ports and big cities destroyed three million homes, resulting in a housing crisis. By March 1944, there were still more raids to come. Vicious weapons such as the V-2 rockets relentlessly damaged the country, killing civilians and destroying more homes.

To address what he called the “housing problem,” then British Prime Minister Winston Churchill declared in 1944 that he would “attack” it “by what are called the prefabricated, or emergency, houses.” The government, he said, hoped to “make up to half a million of these, and for this purpose not only plans but actual preparations are being made during the war on a nationwide scale.” The war government launched the Temporary Housing Programme as a military operation.

Because of inflation and increased costs of materials, Churchill didn’t ultimately reach that 500,000 dwellings target, but, beginning in spring 1946, just over 156,000 prefabricated houses were erected all over the U.K. from Spring 1946. They were assembled in record time—each one took between eight hours and three days to build. One set an actual Guinness World Record, having been constructed in a mere 42 minutes.

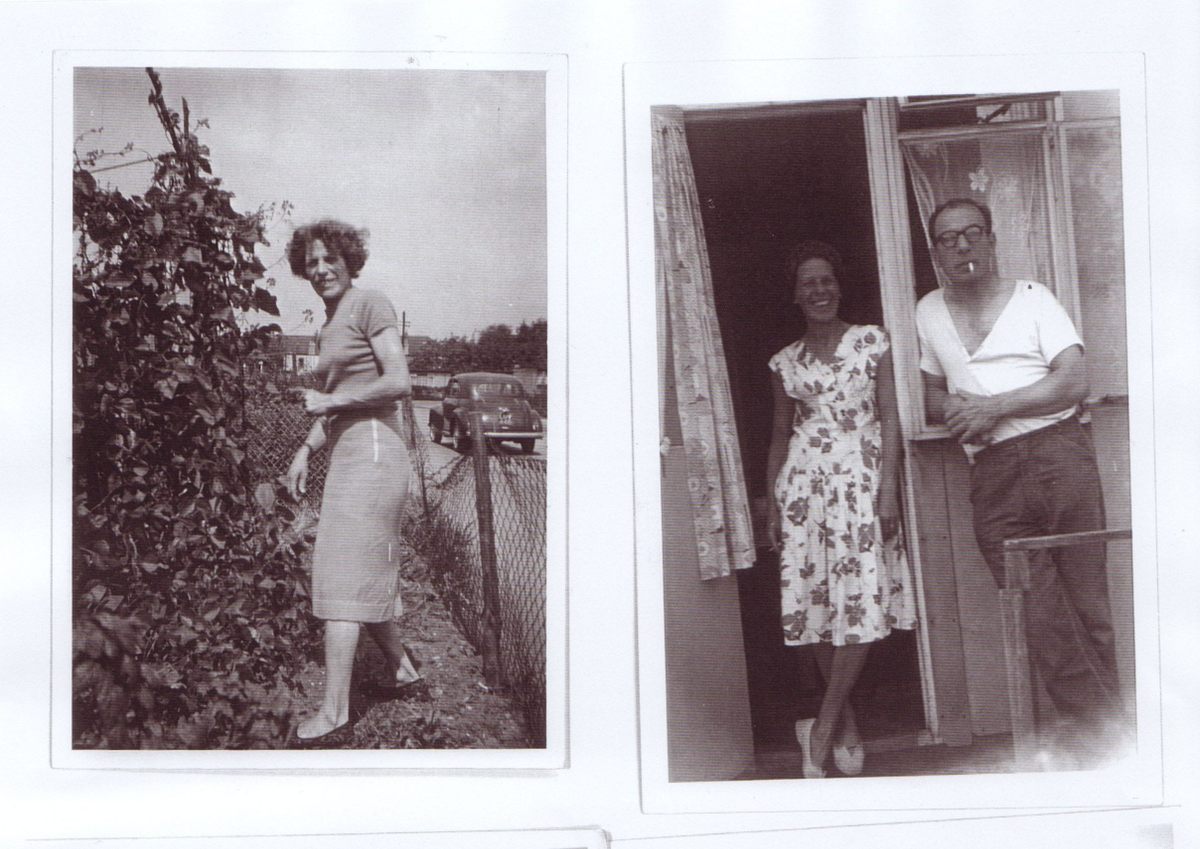

Prefabs sprouted everywhere: on wastelands, parks, bombed-out streets, and even in cemeteries. Some were gathered in little groups, some cleverly laid out on estates like the Excalibur Estate. Built to rehouse servicemen coming back from the war and their families, prefabs were luxury. They had clever designs, all mod cons and the same layout: two bedrooms, a hallway, a living room, a bathroom, interior toilets, constant hot water, and a fitted kitchen—with a fridge, a luxury that only 2 percent of British households had at the time. The homes were all detached so people could grow vegetables, as food rationing that began during the war lasted until the early ‘50s.

Churchill and his war government anticipated a post-war housing crisis as early as 1942 and wanted to implement a successful and efficient housing program—hence the choice of prefabs, which didn’t require any labor skill and could be erected in no time. Prefabs were a national success: residents immediately loved them and strong communities grew out of this successful social housing scheme, which was only temporary and supposed to last 10 to 15 years.

More than 70 years later, there are still thousands of these “palaces for the people,” as they are dubbed, lived in and much loved. A few are also preserved in museums and about 30 are listed by Historic England, a government body dedicated to heritage preservation. But sadly, the Excalibur Estate is doomed to disappear.

Below are some of Excalibur’s residents, in their own words. To find out more about post-war prefabs, visit The Prefab Museum, a museum dedicated to them and prefab life.

Jim Blackender and his wife Loraine lived in their prefab for more than 20 years. They moved out in 2012 after the local authorities offered them a house in Rochester, Kent. Blackender lead the fight against Lewisham Council to preserve the estate, but the battle ended up in a ballot in 2010, in which 52 percent of voters chose “regeneration” of the estate. Regeneration was synonymous with demolition and replacement with double- and triple-story dwellings.

“I liked everything about the prefab,” Blackender said in 2013. “It was the people, the location. When we moved in 20-odd years ago, there was a really strong community. But it’s been left to rot, the Council should have been carrying out repairs, but hardly anything has been done to the estate. It’s depressing to watch it fall into disrepair.”

“The rich, they have their museums, their castles, but for us the poor, there is nothing, they erase our culture.”

“I love my prefab,” said Eddie O’Mahony in 2002. “I wouldn’t swap it for Buckingham Palace even if it included the Queen!” O’Mahony was one of the first residents of the Excalibur Estate. He moved in with his wife and son in June 1946, when the estate was still being built by German and Italian prisoners of war. He bought his prefab in the ‘90s and said, in 2014: “The demolition is breaking my heart. Quite honestly it will be the end of me if I have to move. I close my eyes when I pass the ones that are boarded up. I’ve loved this place from day one.”

O’Mahony passed away in December 2015. He was still living in his prefab.

Christine Gregory’s prefab is a piece of art and eccentricity. There is stuff everywhere—and cats. Twelve of them live with Christine, who is nicknamed the “cat lady of Catford.” She is one of the last residents of the estate and is determined to stay in her prefab: “They are lovely. You just have to do them up a bit from time to time”.

“They are going to pull the prefabs down,” said Ted Carter in 2012. “And of course, the reason is the land is worth millions of pounds now. And instead of 186 prefabs, they are going to put 400 dwellings, whatever a dwelling is.” Ted’s prefab was a living museum full of old radios, as Carter was an expert in repairing them. He passed away in February 2017. He was the last resident of his street.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook