The Ninety-Nines Was Amelia Earhart’s Club for Female Aviators

Runner-up name choices included Gadflies, Noisy Birdwomen, and Homing Pigeons.

In 1929, two years after pilot licensing began in the United States, there were 9,098 men licensed to fly, and just 117 women. Women who flew were often characterized as “girl pilots,” while newspaper reports focused on the color of their hair, or how they balanced aviation with housekeeping.

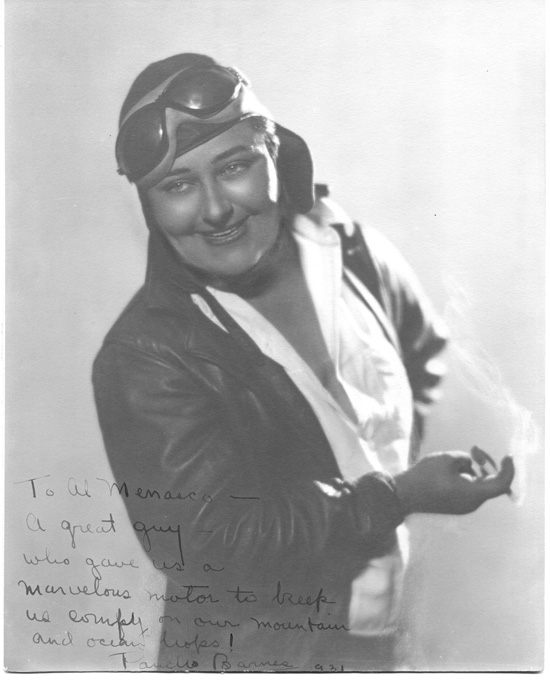

Across nine days of August of that year, 20 women competed in the first ever Women’s Air Derby, starting in Santa Monica, California. Despite being a treacherous race across the continent, in which only 15 participants made it to the finish line, press coverage and even the regulations tended toward sexism. Pilots were not permitted to use any aircraft deemed too powerful for a woman: Opal Kunz was barred from flying her own plane, a 300 HP Travel Air, and had to find one with less horsepower to race. After the humorist Will Rogers noticed pilots adjusting their make-up before take-off, he observed: “It looks like a Powder Puff Derby to me!” To the irritation of Amelia Earhart and other competitors, that name appeared time and time again in newspaper reports—even after both female and male pilots (one was flying with Earhart) died over the course of the event.

The race had not gone to plan. There were whispers of sabotage, attempts to shorten or cancel the race, and consistent claims that women should either not fly at all, or limit themselves to short-haul flights in less powerful aircrafts. And so, beneath the grandstand at the finish line in Ohio, six women expressed an interest in forming some kind of club for female aviators: Amelia Earhart, Gladys O’Donnell, Ruth Nichols, Blanche Noyes, Phoebe Omlie, and Louise Thaden. Eventually, this club would be known as the Ninety-Nines.

Since there were so few female pilots at the time, most knew, or were aware, of one another. Many of those in the Derby had met before, and were friends as much as they were competitors. “They felt their camaraderie called for a more formalized bond,” writes the author and pilot Gene Nora Jessen—an organization where they might support one another, lend a helping hand with professional opportunities, and record their achievements as female pilots.

A letter was duly sent out to all 117 licensed female pilots—86 responded. “It need not be a tremendously official sort of an organization,” the letter stated, “just a way to get acquainted, to discuss the prospects for women pilots from both a sports and breadwinning point of view, and to tip each other off on what’s going on in the industry.” They would have a constitution, a name, and a pin to wear on their jackets. In early November, 26 of these women met over tea at Curtiss Airport in New York state. Against the roars of aircraft, they elected a temporary chairperson, gave chrysanthemums to a pilot recovering from a crash, and determined membership criteria. (Any woman with a license was welcome to join.)

Later that year, Kunz explained in a letter to a fellow female aviator why such a group was so critical. It wasn’t, she wrote, that there was any conflict with male pilots. “This is exactly the opposite to the facts. We want no militant girl pilots. We are not fighting for anything.” Instead, the Ninety-Nines wanted women in aviation to be treated as equals, “rather than spoiled as something rare and very precious.” Instead of overblown headlines about minor female achievements, they wanted women to be treated as peers and given identical opportunities to the men who did, as she wrote, such “marvelous things in the air … We believe that our girls can and will learn to fly as well as the average man, better than many, but it does not seem likely that we will ever equal the remarkable skill of countless men fliers both in our own country and abroad.” That same year, Earhart is said to have proclaimed: “If enough of us keep trying, we’ll get someplace.”

Over the next two years, the group elected Earhart as president and finally landed on a name. Gadflies, Noisy Birdwomen, and Homing Pigeons were all discussed and discarded; instead, they decided to take the name from the number of founding charter numbers. As this number grew, they were first the Eighty-Sixes, then the Ninety-Sevens, and finally the Ninety-Nines. (Women who joined after this point were not considered founding members.)

Cooperation within the group was not always easy to come by. Many of these women were iconoclastic and fiercely independent: It took many months before formal leadership was put in place, delayed further by the death of Neva Paris, the group’s election organizer, in a crash in Georgia. Even then, some were unhappy about the direction the group had taken. Kunz founded a parallel group with more of a focus on military defense, devoted to training female pilots to replace men killed at war. The short-lived Skylarks, whose purpose has since been lost to time, was another competitor, founded by five of the original 26 pilots.

The late 1920s, Jessen wrote in a 1979 history of the group, were “aviation’s adolescence: a time to prove oneself and shout to the world, ‘Here I am!’” Women aviators had even more to prove. The Ninety Nines were there to support one another, but they were also codified evidence that female aviators had every reason to exist and would continue to do so, whatever the cost.

For these women, even tremendous success did not necessarily equate to being taken seriously in a professional context. Early female pilots sometimes received inflated salaries for the publicity they brought in—but after their star dimmed, that experience seemed to count for very little. Ruth Elder was nicknamed the “Miss America of Aviation” and set a record in 1927 for the longest flight ever made by a woman. But despite this fame, her career eventually led her to a desk job as the secretary to an aviation executive in Culver City, California.

In July 1941, a year before many American women began to contribute to the war effort, the Ninety-Nines held a critical meeting in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A letter to U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt promising “to serve individually and collectively” was drafted up and sent. Earhart had disappeared some four years earlier: That year, they chose the first recipient of a scholarship in her name, set up to support an aspiring female pilot’s advanced flight training. This once-informal group now had the resources to train up-and-coming pilots, a temporary national headquarters alongside the National Aeronautics Association, and their own song. (Its rousing chorus ends: “Keep that formation over the nation/with the song of The Ninety-Nines.”)

The same meeting resulted in women pilots being welcomed to the volunteer Civil Air Patrol, where they were able to make a substantial contribution as aviators, flight instructors, and at air warning posts. The Ninety-Nines began to train more and more women to fly, with the launch of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots, a civilian women pilots’ organization that at its height had 1,074 members. (It was dissolved after the end of the war.)

“Paradoxical as it may be,” Nessen writes, “during the darkest hours of war, some of the brightest pages in the history of women in aviation were written.” Women pilots had more opportunities than ever before to fly powerful aircrafts, lay smoke screens, and take part in photographic and radio-controlled missions. All of this they did exceptionally well, setting a new safety record in military aviation. In short, your plane was less likely to crash if it had a woman at the helm.

The helmets and goggles of the founders are a distant memory, but the Ninety-Nines still exists, and thrives, today. It has well over 5,000 members from around the world, including students on their way to the skies, and provides scholarship and training opportunities for young women who hope to be pilots. It still has good cause to do so: Women are still a rare sight in cockpits, making up about three percent of commercial pilots. From 1975, its permanent headquarters have been in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, with the second floor museum dedicated to founding and historic members. In that early letter, Kunz wrote: “It should be an inspiration to all American girls to learn to fly, to develop skill, and fit ourselves for the splendid work ahead in aviation.” The same spirit applies today.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook