Maps Have the Power to Shape History

A groundbreaking female cartographer charted the evolution of the United States—and the dispossession of Native Americans.

In 1828, Emma Willard was 41 years old—only slightly older than the United States of America itself, if you start counting from 1789, when the U.S. Constitution came into force. Of course, there were others ways to count, too. The country was a solid 45, if you mark time from the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War and recognized American sovereignty, and a little over 50, if you start counting from 1777, when the Articles of Confederation were signed. In 1828, the story of the country was still malleable, only just being formed into a shape that would harden into history. Willard’s contribution to that process was to make maps.

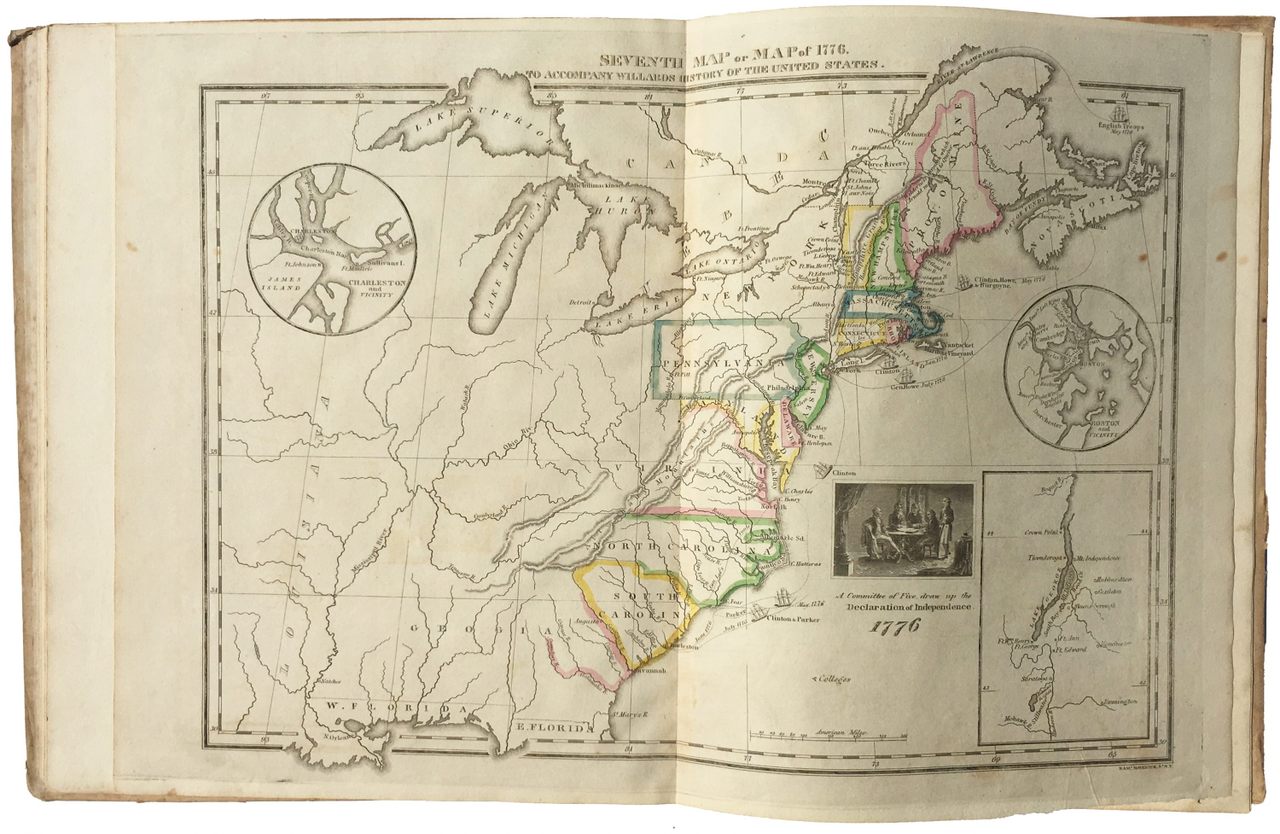

Willard is one of the first, perhaps the very first, female mapmaker in America. A teacher, pioneer of education for women, and founder of her own school, Willard was fascinated with the power of geography and the potential for maps to tell stories. In 1828, she published a series of maps as part of her History of the United States, or Republic of America, which showed graphically how the country, as she understood it, had come to be. It was the first book of its kind—the first atlas to present the evolution of America.

The book began with map (below) that was unusual and innovative for its time. It attempted to document the history and movement of Native American tribes in the precolonial past. Willard’s atlas also told a story about the triumph of Anglo settlers in this part of the world. She helped solidify, for both her peers and her students, a narrative of American destiny and inevitability.

“She’s an exuberant nationalist,” says Susan Schulten, a historian at the University of Denver and the author of Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America. “She’s extraordinarily proud of her country.”

It’d be wrong to call Willard a feminist, but she believed in the intellectual potential and education of women. At the time, education for girls was limited to certain “softer” subjects—geography among them—but Willard knew that girls could tackle philosophy and natural sciences with as much rigor as boys. Before she was 20, she was running a school; before she was 30, she had founded her own. Her school was the first in the country to educate woman at a college level, and Willard’s textbooks were some of the best-selling in America.

But her maps were among her greatest innovations. At the time, as Schulten writes, “Americans discovered that maps could organize and analyze information.” Willard believed that maps should capture information about the sweep of history, a story that unfolded across time and space. She created maps as a pedagogical tool, with the idea that an image could help cement lessons in the minds of her students. (She believed, like most educators of her time, in the power and precedence of memorization.) Her historical atlas was one of the major and influential results of these efforts.

In all, her atlas included 12 maps, though that number varies a little across editions. The one depicting the movements of tribes she called an “introductory” map, outside of historical time; American history, as she conceived it, began in the period from 1492 to 1578, when European exploration of the land across the Atlantic began. Each map that followed moved along the story of Anglo settlement and increasing control of American land, highlighting key events, from the Pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth Rock to the Treaty of Paris to the War of 1812, and culminating with the division of states at that time.

But that introductory map of tribal movements already hints at this ending. The boundaries of the future states are already there, in faint outlines. Even as she gave Native American peoples more attention than her contemporaries had, she helped to form a story that wrote them out of American history.

“She often framed the native tribes in terms of respect, sometimes as welcoming the colonists while other times as constituting a formidable obstacle; but more generally she accepted the removal of these tribes to the west as inevitable,” Schulten writes, in an article about Willard’s mapping of “settler society.”

After the first map, once “history” begins, the tribes appear only when they’re in conflict with or otherwise influencing Anglo-American society. In later versions of her historical atlas, Willard had illustrators depict Chief Powhatan as a “great-man-child” and other native people as stupified by European technology. Though it’s possible to imagine that Willard’s inclusion of tribal movements in her book represents a critique of settlers’ attitudes toward native people, ultimately her views are typical of Americans of her time: God meant for “civilized” people to take this land from “savages.”

What’s innovative about Willard’s work, cartographically speaking, is the way she tried to represent time. “Even though she sees it as inevitable that natives will disappear, she’s collapsing centuries onto a single image,” says Schulten. “She’s trying to map time in a different way as a prelude to what comes next. It’s really an argument that has everything to do with Anglo-America’s vision of the country. She’s a pioneer in that respect.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook