A Nun’s 450-Year-Old ‘Last Supper’ Makes Its Museum Debut in Florence

Plautilla Nelli was likely the first woman in history to paint the iconic biblical scene.

In the early 1990s, Jonathan Nelson was searching for a little-known but historic Florentine painting: “Last Supper” by Plautilla Nelli, an Italian nun who is said to have taught herself to paint in the 16th century. Nelson, an art historian, was working on the first-ever book about Nelli, but he wasn’t sure whether her painting of the famous Biblical scene still existed, or where, exactly, it had ended up. He tried the museum of Santa Maria Novella, a Dominican church where it was last seen in the 1930s. When he couldn’t find it there, he asked the father superior for permission to enter the Santa Maria Novella monastery.

“It was in the refectory used by the friars,” says Nelson, who now teaches at Syracuse University’s Florence Program. “I had to go see it right after lunch.” A refectory is a dining hall or cafeteria used by nuns or monks, traditionally decorated with a Last Supper, and this refectory, Nelson recalls, was far from monumental. “This was a simple, modern room that had this Renaissance painting on the wall, and beneath it was a Formica table that had the remains of the friars’ lunch,” he says.

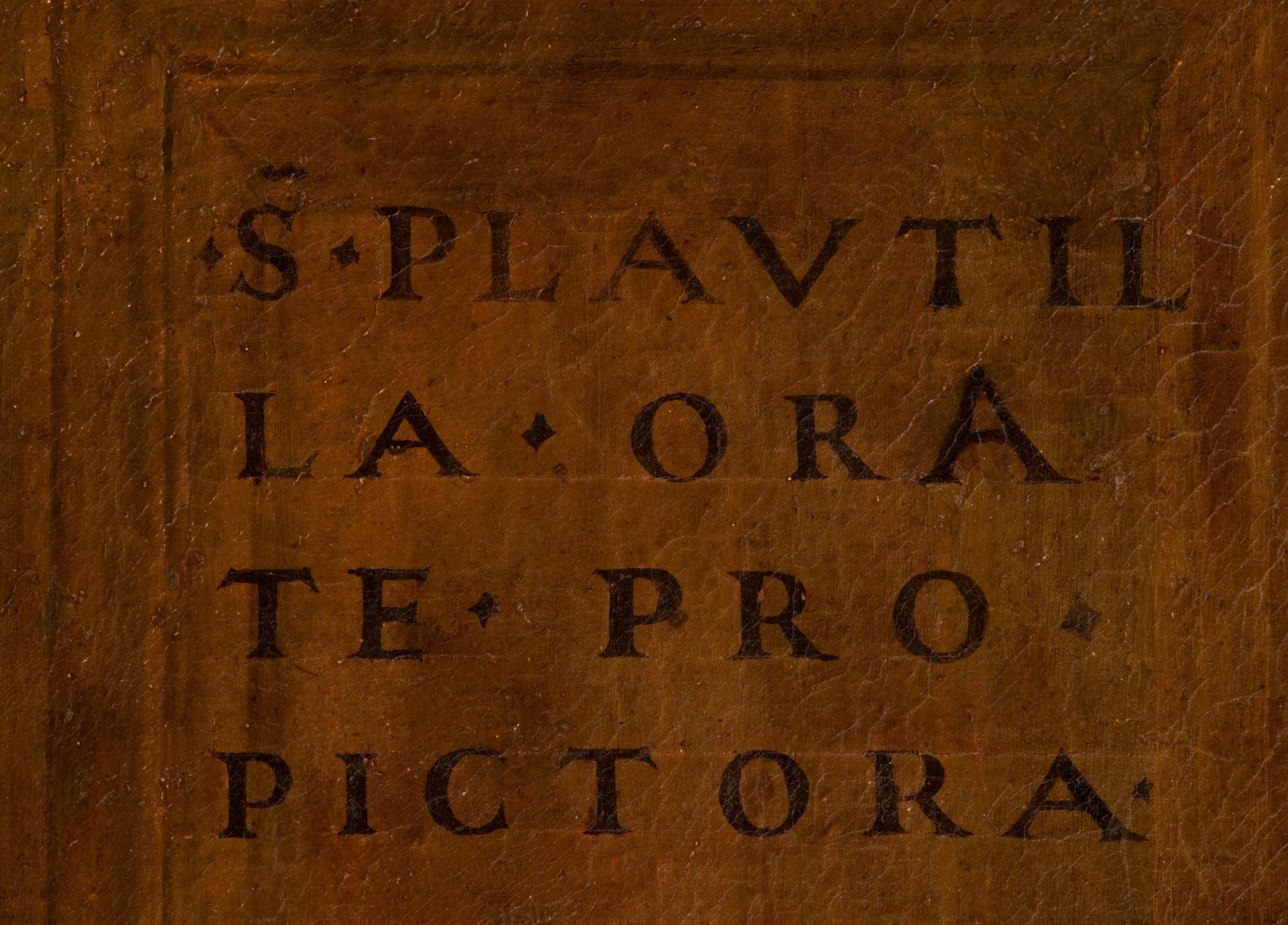

Nelson didn’t even notice Nelli’s signature in the painting’s upper left corner, until he returned to study the work with conservation-grade lighting. “It says orate pro pictora, which is ‘pray for the painter,’” he says. “So the scene you should imagine is that, with some dirty plates next to us, in a dirty, humble room, we’re looking at an unknown work that virtually no one had ever seen. And we found the artist speaking to us, asking us to pray for her. It was a moving moment.”

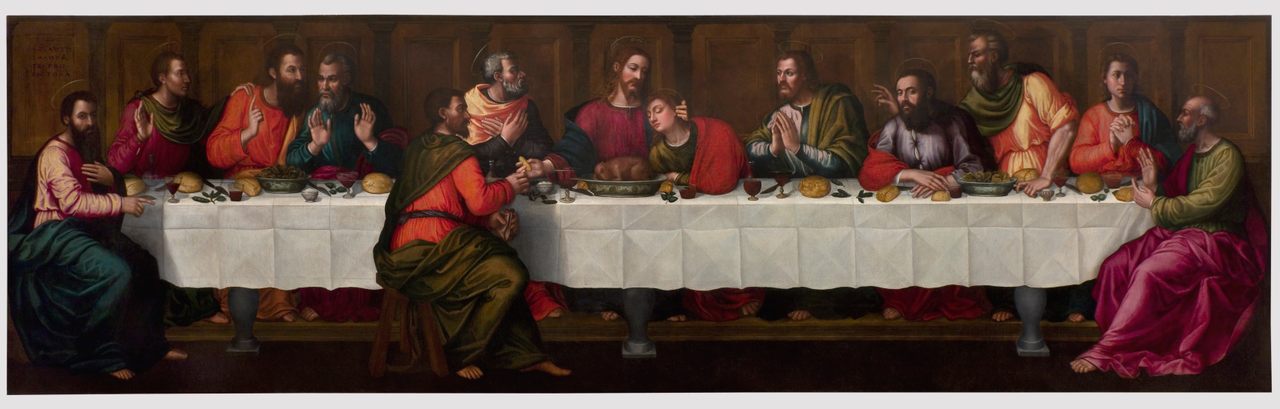

Nelli’s “Last Supper,” completed around 1568, was remarkable for several reasons. Of eight iconic paintings in Florence that showed Jesus dining with his 12 apostles, six were frescoes, painted directly onto wet plaster and nearly impossible to move. But this one was portable, painted on a canvas that had moved several times over the centuries. More strikingly, this was the first-known depiction of the Last Supper by a woman worldwide. Both these facts help explain why the painting still exists—and why it was just unveiled in public for the first time in 450 years.

Plautilla Nelli first picked up a paintbrush at Florence’s Santa Caterina da Siena convent, which she entered at age 14 in the footsteps of her older sister. The convent attracted many creative women from respectable Florentine families, and within its cloistered walls, Nelli and her sisters painted and sold manuscripts, devotional paintings, and embroidered textiles. Nelli is often described as Florence’s first woman painter, and she was either taught how to paint by another nun, or, more likely, taught herself.

Soon she was painting large, elaborate compositions, highly uncommon for women at the time. Her “Last Supper,” created for the refectory of Santa Caterina, was especially ambitious. At roughly 23 feet wide and six-and-a-half feet tall, the canvas was almost as long as Leonardo da Vinci’s famous take on the subject, and filled with life-sized figures. Nelli’s grand project would have required scaffolding and assistants, an expensive undertaking that the nuns proudly paid for themselves.

Nelli didn’t paint her “Last Supper” background to look like the dining hall it was designed for, a trick other artists used to make the scene relatable. Instead, she showed Jesus and his apostles dining on the same food that Santa Caterina’s Domincan nuns ate: a whole roasted lamb, bread, wine, heads of lettuce, and fresh fava beans—the last two dishes unprecedented in any depiction of Christ’s last meal. The fava beans were a wink to local cuisine, a Florentine specialty normally eaten by peasants (and nuns).

Giorgio Vasari, the early art historian, saw Nelli’s “Last Supper” when it was still surrounded by dining tables at Santa Caterina. “She shows that she would have done marvelous things if she had enjoyed, as men do, opportunities for studying, and devoting herself to drawing and representing living and natural objects,” he wrote in the 1568 edition of his book Lives of the Artists. Vasari’s comment recognizes Nelli’s talent, but also hints at the fact that Nelli was limited by what she could teach herself. Nelli couldn’t paint in the highly technical and physically demanding medium of fresco, which was then considered strictly a man’s job.

The nuns dined alongside Nelli’s oil painting for over two centuries—but then came a new era. In the late-18th century, Napoleon’s forces invaded Italy and began to suppress religious orders. In 1808, the Santa Caterina convent was dissolved, and Nelli’s “Last Supper” was almost lost to history.

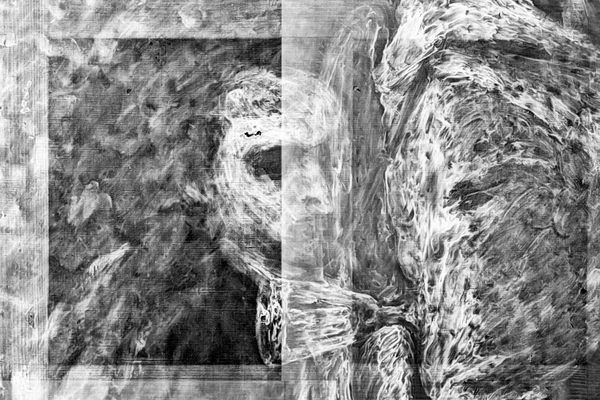

It is said that when God closes a door, he opens a window. When the powers-that-be shuttered Santa Caterina, Nelli’s masterpiece began a journey that would ultimately allow the public to see it. The helpfully portable oil painting was rolled up and moved to a still-active Dominican order, Santa Maria Novella, just a mile away. It migrated a few times within its adoptive home, first to the attic (where some damage and paint loss occurred) and then to a grand 14th-century refectory that would serve as a long-term home.

By the 1930s, it was in the smaller, more modern dining hall where Nelson spotted it. It remained there even after Santa Maria Novella’s historic refectory opened as a museum in 1983. “The monks wanted it in their dining hall, essentially,” explains Linda Falcone, director of Advancing Women Artists (AWA), an American nonprofit that identifies and restores art by women in Tuscany. “They chose to have it in their private quarter.”

The friars were supportive of restoration efforts on Nelli’s “Last Supper,” but they didn’t want to permanently release it from their refectory. “They saw it as part of their day-to-day life and were very concerned that I and other art historians and officials would want to remove it from their dining room,” Nelson recalls of the monks’ attitude when he saw the painting in the 1990s. “Which is exactly what happened.”

As it happened, AWA advocated for the restoration and relocation of the painting. Jane Fortune, the late founder of the nonprofit, embarked on a 10-year project to raise $220,000 for conservation, research its legal ownership, and negotiate its placement in a public space. In a strange twist of fate, Napoleon’s reforms not only closed Santa Caterina, but also provided the AWA with a legal justification for moving the painting to a museum: Under Napoleon’s law of suppression, the “Last Supper” became public property when it was removed from the convent.

It’s not easy to relocate a monumental painting in Florence—a city that can feel more like a museum than a metropolis, with every church, building, piazza, and bridge packed with original cultural treasures. For one thing, there’s the tricky matter of moving a wall-sized canvas. Not wanting to roll the “Last Supper” up like Napoleon’s henchmen, six art movers carefully conveyed the painting out of Santa Maria Novella’s refectory.

“They built scaffolding and had mechanical things to lay the painting flat and lower it,” Falcone recalls. “Almost like Legos, or a car jack.” The art handlers hoisted the painting into a truck and drove to a restoration studio, where they built more scaffolding to bring it in through a window. “There are two flights of stairs to get to the first floor,” explains Falcone. “The painting couldn’t make the turn.”

Of course, you can’t just hang a painting anywhere you want in Florence. “Whenever you put a painting in a public museum, there has to be a historical justification for it,” Falcone explains. The Santa Maria Novella Museum seemed like the most suitable new home, because it is part of the same church complex and has a refectory that is big enough to accommodate it. It will also share the space with another Florentine “Last Supper,” painted around 1582 by Nelli’s contemporary, Alessandro Lori. “It’s going to be placed in an environment in which the painting is dialoguing with other paintings of its time,” Falcone says.

Falcone hopes this dialogue adds to a different Renaissance narrative, one in which more women artists have a seat at the table. Nelli’s “Last Supper” is the only permanently exhibited original artwork by a woman at Santa Maria Novella, which has become a hub housing in situ masterpieces by Italian Renaissance greats such as Masaccio, Brunelleschi, and Ghirlandaio (made with help from his apprentice, Michelangelo). Starting in October 2019, visitors can buy tickets to see it any day of the week.

After the long and winding history of Nelli’s “Last Supper,” its installation in Santa Maria Novella’s museum was surprisingly straightforward. Nothing had to be cleared from the wall of the rectangular refectory to make room for her “Last Supper.” A 23-foot stretch of wall was already available, sandwiched between the historic monastery’s basilica and grand cloister. “The wall was waiting,” says Falcone. “It was waiting for Nelli.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook