How to Feed a Megacity Like the Aztecs

The chinampas that nourished Tenochtitlan may hold the key to better urban gardens.

When conquistador Hernán Cortés reached Tenochtitlan in 1519, he beheld a floating city. The temples and palaces of the Aztec capital gleamed white from an island in the middle of a vast lake, all spread under a searing blue sky. With an estimated population of 200,000, roughly the size of contemporary Paris, the city overflowed with people. Around the metropolis, an archipelago of lush islands emerged from the lake’s glassy surface, overflowing with plants.

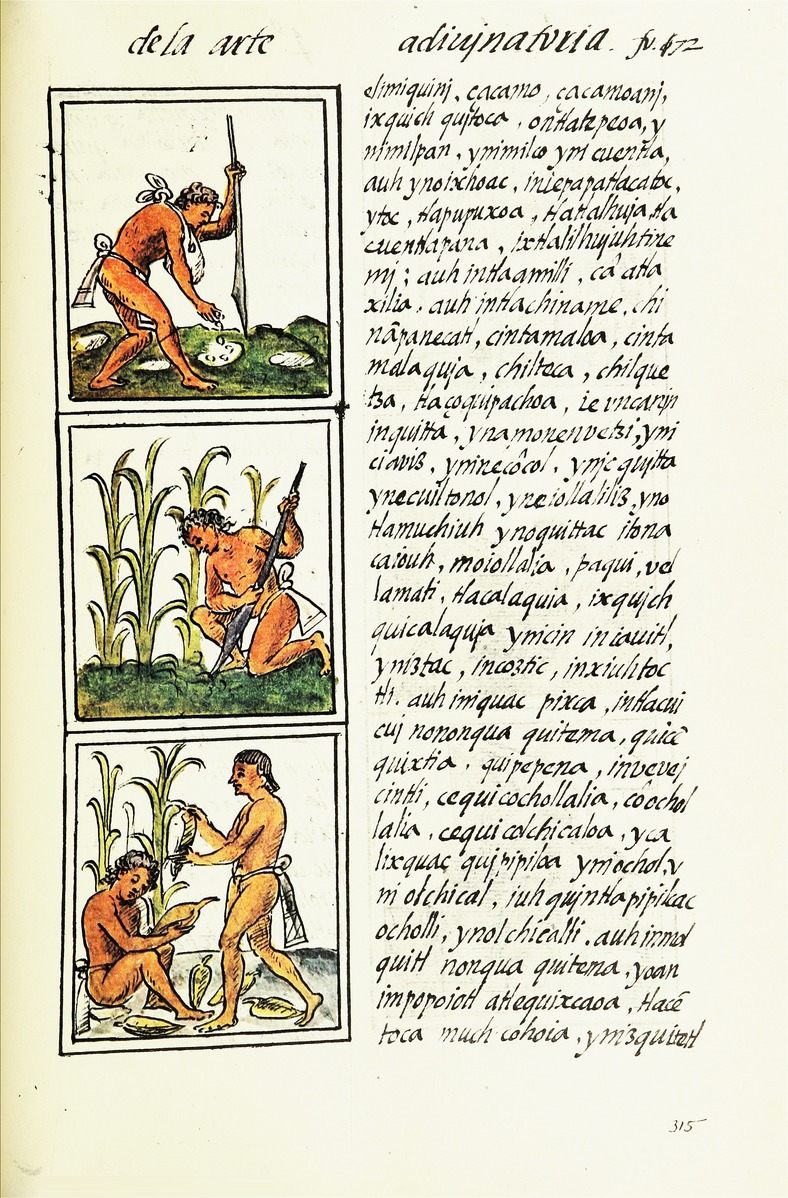

These were the floating gardens, or chinampas, that fed the Aztec Empire. Constructed of layers of earth taken from the lake bottom, and held together by the tangled roots of diverse and rotating crops, chinampas are rich islands of soil that can produce up to seven harvests a year. The result of Aztec adaptations of earlier agricultural forms, chinampas’ efficiency has gained them UN recognition as a marvel of agricultural ingenuity.

Today, the parched asphalt streets of Mexico City—built on top of the filled-in lake that once bore Tecnochtitlan—show little trace of these lush Edens. But if you head to the southern borough of Xochimilco, where the cusp of the city touches the countryside, the landscape still bears an ancient crisscross of canals. Some of these chinampas have been in use since Aztec times. Most have been built and deconstructed again and again, part of a living current of agricultural knowledge flowing through centuries.

“The way they are built is almost identical to the way they were built in pre-Columbian times,” says Roland Ebel, a Postgraduate Research Associate in Health and Human Development at Montana State University.

But today’s chinampas face distinctly modern problems. Thanks to rampant urban development, the waterways are fetid with runoff, clogged with algae, and poisonous with heavy metals. Meanwhile, recreational boating—trajinera boats full of tourists and locals, who snack on elotes and request songs from floating mariachi bands—has filled the waterways with trash. Still, working chinampas dot the canals, the moist soil of their surfaces diligently tended into fruit and produce.

For Ebel, this landscape is a reminder of Mexico’s past, and a fertile promise for the future. He began studying chinampas while at the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico. While chinampas remain a living, though threatened, agricultural system in Xochimilco, he says, “Most [academic] work sees chinampas as a historic farming system which is worth conserving, but not as an opportunity for contemporary urban farming.”

That got him wondering: Could the urban planners of today’s vast, increasingly food-insecure cities learn from Aztec agriculture?

Ebel’s recently published study suggests they can. Ebel compared features of traditional chinampas with similar “floating” or canal-based agriculture systems from around the world, including in Peru, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Illinois. He found that chinampas are uniquely efficient and adaptable to cities with lake access around the world. Because fields in the chinampa system are surrounded by canals, with plants’ roots sucking water from their swampy surroundings, chinampas require no irrigation and relatively little watering. At the same time, the islands’ dense and varied mix of plants, which is a form of permaculture, yields frequent harvests without the need for pesticides.

Ricardo Rodriguez, CEO of travel company De La Chinampa A Tu Mesa, or “From the Chinampa to Your Table,” has firsthand experience of the benefits of this rotating system. He was not involved in Ebel’s study, but owns and farms a chinampa in Xochimilco, where he leads culinary tours. He says chinampas’ crop diversity is key to their effectiveness, in contrast to industrial monoculture. “Mono agro destroys lands,” says Rodriguez. “If you have permaculture, you have life.”

While Ebel’s study looks to the potential for implementing chinampas globally, the most serious threats to this system are close to home. Over the past several decades, development in Mexico City’s southern fringe has picked up. From 1989 to 2006, the percentage of land in Xochimilco covered by chinampas reduced from 7.4 percent to 2.5 percent. If these patterns continue, researchers project that most chinampas will disappear, eaten up by urban development, by 2057.

This isn’t just bad for farmers. It’s also bad for Mexico City as a whole, a reflection of a broader policy that has driven the megapolis to the brink of environmental disaster. As though in an act of revenge from the submerged Aztec capital, the city is sinking, the clay of the filled-in lake sagging like an old mattress. Meanwhile, rampant development has limited urban greenspace and exacerbated drought. Chinampas are both a casualty and a marker of this looming catastrophe. Saving these traditional systems—and creating a more ecologically resilient Mexico City—requires rewriting city policy to favor local agriculture and sustainability, rather than overdevelopment.

Rodriguez, the owner of De La Chinampa a Tu Mesa, has spent the past 12 years advocating for this shift in priorities, from the ground up. He begins with local farmers, who often struggle to bring crops to market. “They don’t have opportunities to sell their production,” he says. So he connects them with restaurants, cafes, and organic food stores hungry for local produce. Rodriguez also leads culinary tours that introduce visitors to Xochimilco’s food traditions and the farmers that enable them.

Heavy tourist traffic has exacerbated the canals’ pollution. But Rodriguez hopes that this more purposeful exposure to chinampa agriculture can help inspire the political will to invest in floating gardens, not just for recreation, but for food. “We need to create consciousness,” he says. In doing so, Rodriguez summons an alternate vision to the one the Spanish imposed on Tenochtitlan. Rather than turning a life-giving lake into a parched, paved city, his is a vision of fertile water filling in the cracks of a thirsty land.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook