FOUND: The Earliest Known Draft of the King James Bible

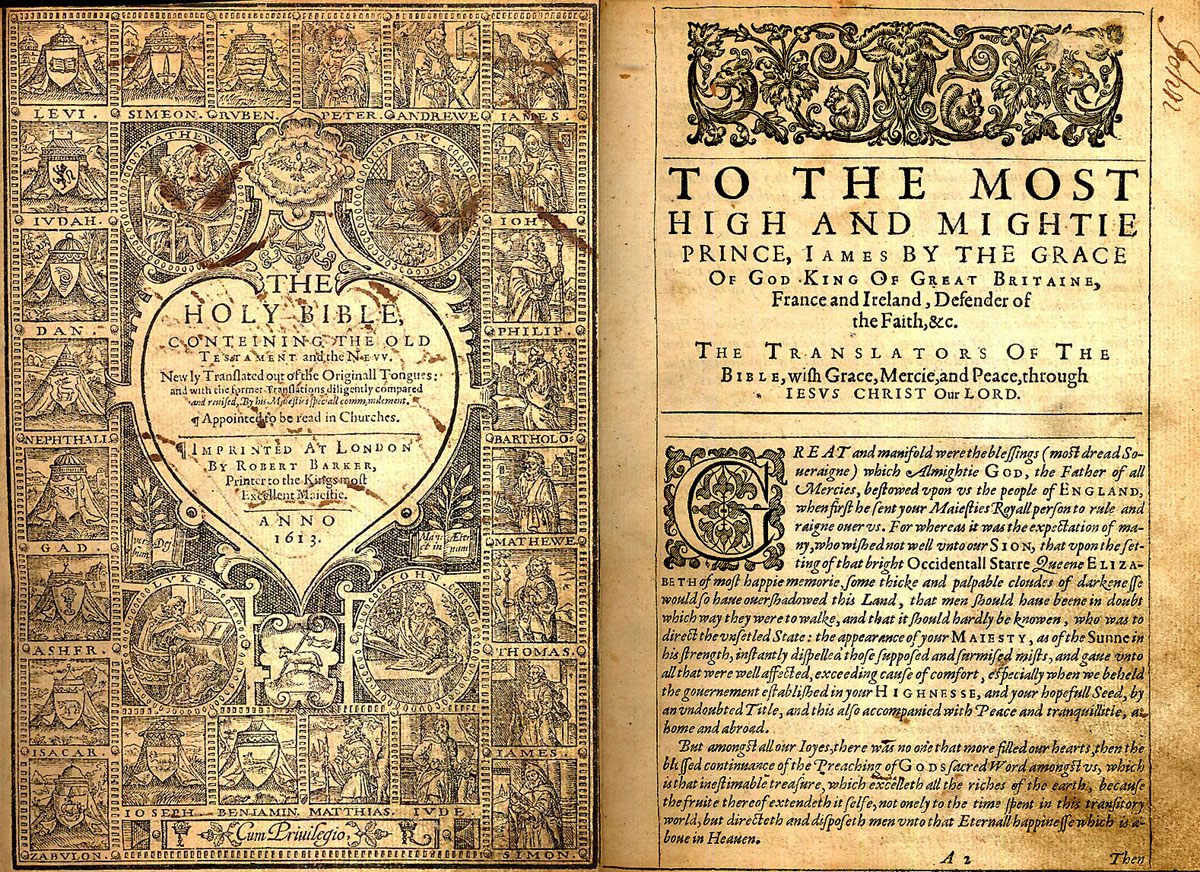

An early edition of the King James Bible (Image: Private Collection of S. Whitehead/Wikimedia)

In 1604, King James I gave six groups of translators a very important task: produce a definitive English translation of the Bible for the Church of England.

The King James Bible, as it came to be called, was finished in 1611. Translated from the original Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, it was intended to be an alternative to earlier Puritan translations, which the king found seditious.

Only three copies of the translators’ drafts were known to exist. But now Jeffrey Alan Miller, an assistant professor at Montclair State University, has found the earliest known draft of part of the King James Bible, he reports in the Times Literary Supplement.

The draft is also, writes the New York Times, “the only one definitively written in the hand of one of the roughly four dozen translators who worked on it.”

Like so many historically important and valuable objects, the manuscript was just sitting in an archive. It was in the papers of Samuel Ward, one of the translators, who went on to become the master of the University of Cambridge. For many years, his papers were uncatalogued; when they were organized in the 1980s, the draft was logged as a “verse-by-verse biblical commentary.”

When Miller was researching a book about Ward, he found the document, “an unassuming notebook about the size of a modern paperback, wrapped in a stained piece of waste vellum,” says the Times. When he examined it more closely, he began to realize that the book contained Ward’s notes on an existing English translation of the Apocrypha. He considered word choices, looked at the original Greek and jotted down possible alternatives—some of which made it into the final King James translation.

Part of what makes the draft so interesting is that it shows how the translators worked. They were supposed to work collectively on their translations, instead of assigning out certain parts to individual translators. But the notebook indicates that the Cambridge group at least began by assigning out sections. It appears that Ward finished his, and then picked up slack from another translator by starting work on a second section. This backs up an account from another translator, describing a similar system of work.

The translation decisions were made more collaboratively, though. As Miller writes in the Times Literary Supplement, not all of the suggestions that Ward jotted in his notebook made it into the final translation. He was, after all, a young Fellow of the college at the time: even if he was entrusted with some of the work of translation, King James’ instruction had been clear. No one person was to be the translator of any section of the Bible.

With these newly discovered manuscripts, we know understand that much better how the scholars assigned this task created the book that would be one of the most influential in the world for centuries to come.

Bonus finds: Ancient mammal with spiky hair, ancient human teeth that could rewrite migration history, aliens?

Every day, we highlight one newly lost or found object, curiosity or wonder. Discover something unusual or amazing? Tell us about it! Send your finds to [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook