How Profit and Prejudice Built a Family’s Human Skull Collection

Fowler & Wells created a “Phrenological Cabinet” on the racist belief that skulls held secrets about human nature.

On April 15, 1841, the day before his execution, Peter Robinson welcomed an artist to his New Jersey prison cell. A possible inspiration for Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Robinson was sentenced to death for killing his creditor and hiding the body beneath his floorboards. He turned away clergymen offering to pray for him, but he didn’t seem to mind the artist, who had been sent by a family of skull-obsessed pseudo-scientists. Whatever his hesitations about preserving his soul, he submitted willingly to the messy procedure of preserving his head as a plaster cast.

Robinson was hanged the following day. The authorities delivered his body to friends and family, as he had requested, hoping to evade the corpse-hungry medical school market. The artist, meanwhile, delivered the cast of his head to the New York firm of Fowler & Wells.

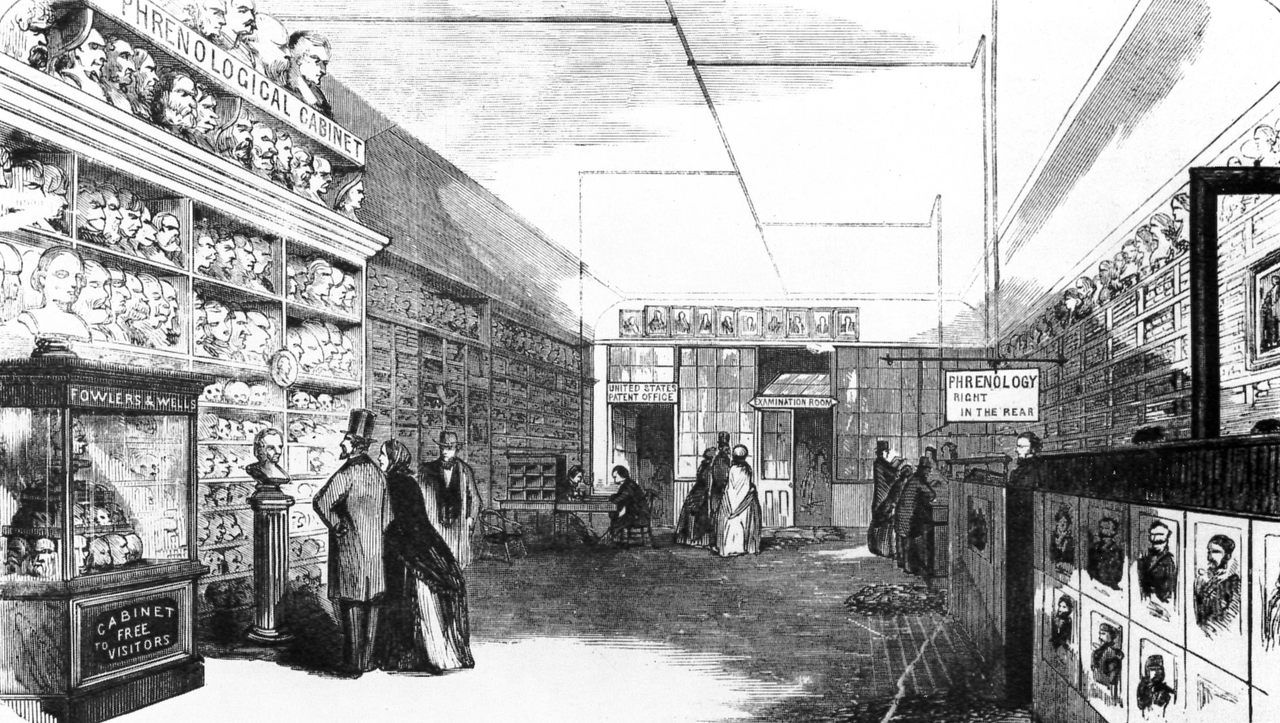

The brothers Orson and Lorenzo Fowler, their sister Charlotte, and her husband Samuel Wells were phrenologists who believed the size and shape of the human skull contained secrets about human nature. They eagerly acquired cranial “specimens” of infamous men like Robinson. Their collection was enshrined in the “Phrenological Cabinet,” a display of casts, busts, portraits, and skulls that eventually grew to nearly 2000 items.

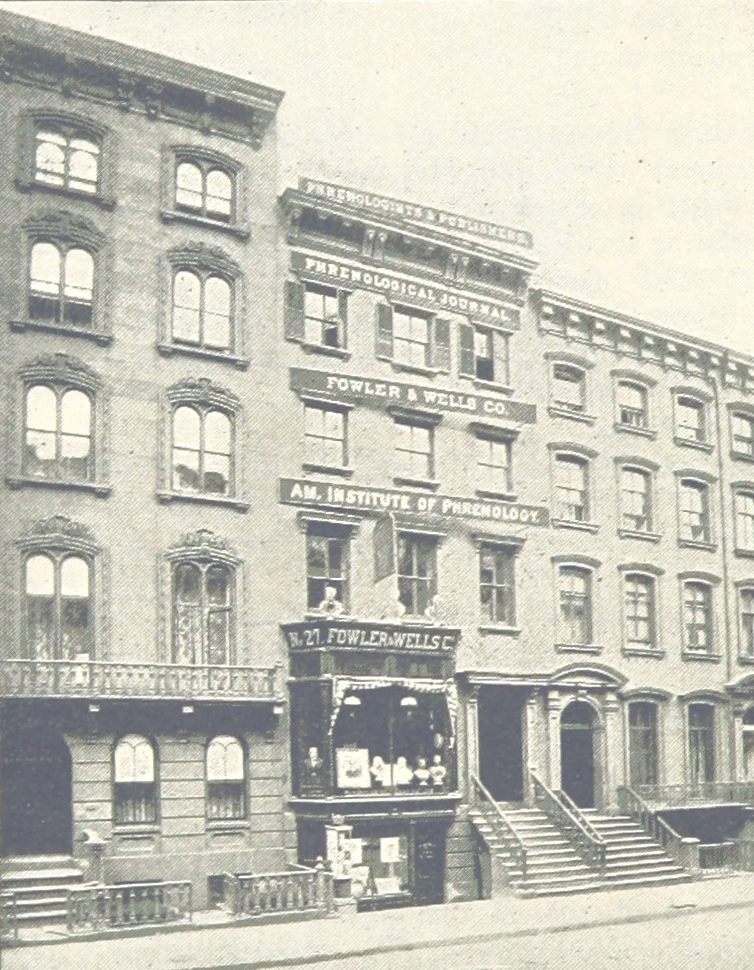

Founded in the 1830s, Fowler & Wells built a booming brand from books, pamphlets, public lectures, and “readings” of the heads of both living and dead. The idea that meaning of any kind could be assigned to cranial contours today seems like quackery, at best. In the 19th-century United States, however, there was a fever for the field, and none spread it more zealously than Fowler & Wells.

Their popularity was due in large part to the Phrenological Cabinet, housed until the 1850s near the corner of New York’s Beekman and Nassau Streets. In her 1971 book Heads and Headlines, the independent scholar Madeleine B. Stern wrote that the Cabinet combined “the attractions of [P.T.] Barnum’s American Museum, a freak show, and a scientific repository,” and by the 1840s, it “was fast becoming one of New York’s show places.” In 1844, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal called it “one of the most curious museums in America.”

The Cabinet included replicas of famous busts depicting such men as William Shakespeare, Napoleon Bonaparte, and George Washington, as well as casts of “persons of eminence in talent and virtue.” They advertised specimens from “pirates, murderers, robbers, thieves, forgers, gamblers, pickpockets,” and more. Peter Robinson, who was described as having a “base, coarse, animal character,” sat among these.

Fowler & Wells spared no expense in filling the Cabinet. In his preface to an 1875 catalogue listing some contents of the Cabinet, which by then was located on Broadway near Astor Place, Samuel Wells described how “an artist was kept in requisition” to obtain casts of the famous and infamous, “and large sums of money have thus been expended sometimes, as a premium, for obtaining the head of some singular or vicious character.” In 1864, Wells specified that over the previous 25 years, they had paid “not less than $30,000” for busts, casts, and skulls. In today’s currency, that’s nearly half a million dollars.

As Fowler & Wells grew in popularity, they began soliciting and receiving skulls from “friends of Phrenology.” Skull and human remains collecting was a robust industry at the time, thanks in part to demand from medical schools and natural history museums, but Fowler & Wells became another lucrative destination. In the 1875 catalogue, after noting the “large sums” spent on skulls, Wells continued: “Travelers, captains of ships, soldiers on the frontier, have brought home specimens of the skulls of the different nations of the world, and contributed them to this collection.” Here, “contributed” probably meant “sold to.”

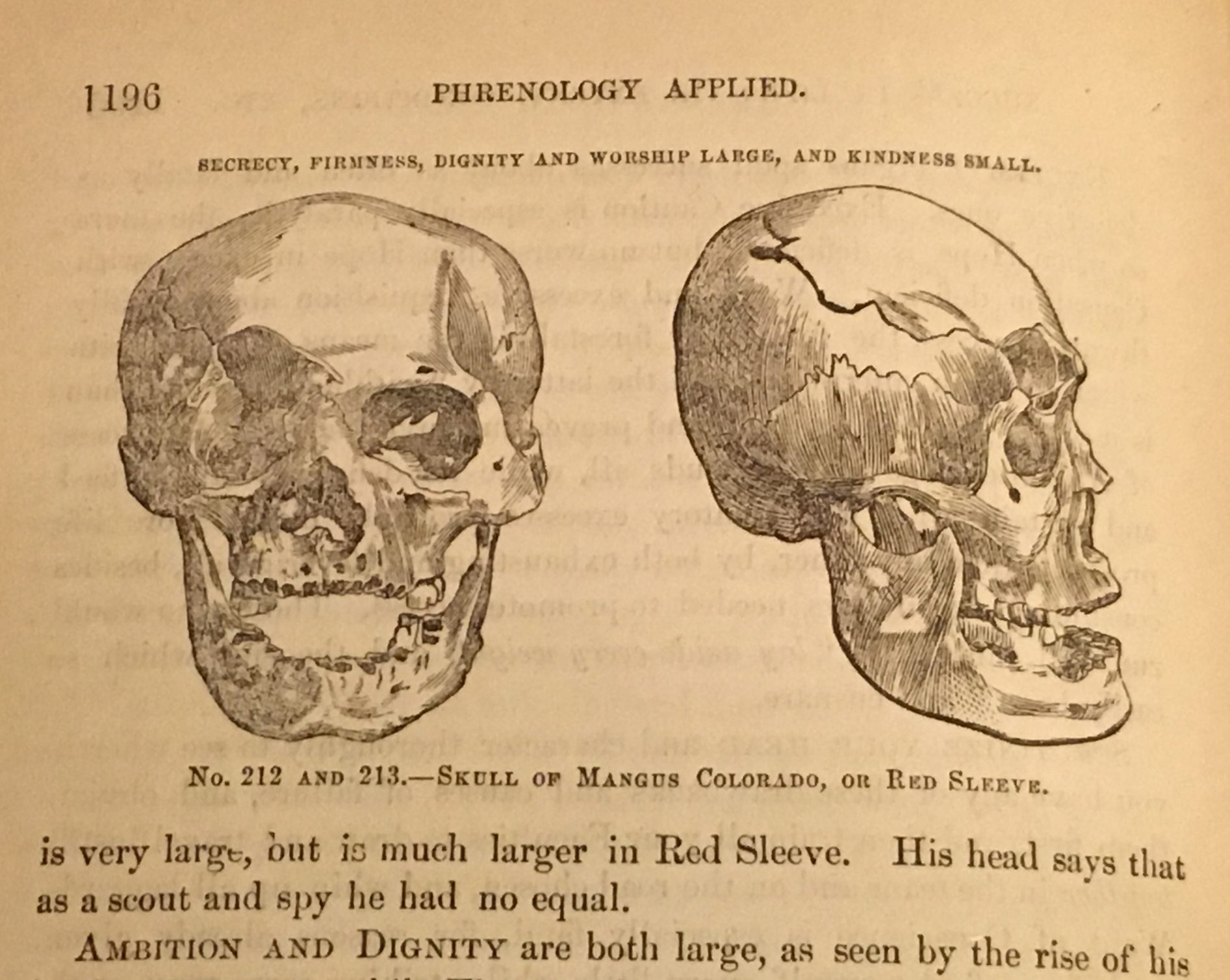

There is no known list of “contributors,” but many remains were acquired in suspect and even violent circumstances. “From the battlefields of Mexico,” Stern wrote, Samuel Wells “received skulls with gunshot wounds or saber marks.” These battlefields very likely included those of the Apache Wars, waged during the second half of the 19th century by U.S. troops in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico. In fact, Orson Fowler’s 1873 book Human Science provides a detailed reading of the skull of legendary Apache chief Mangas Coloradas, whom American soldiers tortured, shot, and killed in in 1863. After his murder, an Army surgeon decapitated him and presented the skull to Orson.

The extent of Fowler & Wells’s complicity in specific atrocities is difficult to measure, because unlike the casts, which were listed by name or description in the Cabinet catalogues, only a handful of their nearly 1500 skulls were ever named. This is likely because Fowler and Wells believed them to convey racial characteristics, rather than the unique qualities of an individual. A Cabinet observer in 1870 described, using the racist language of the time, a wall filled with the “skulls of Greenlanders, Indians, Kaffirs, Australians,” and more. For Fowler & Wells, such skulls were important primarily as representative specimens within a hierarchy of races. In Human Science, among many other publications, Orson portrays “Caucasian races” as superior to those of “Indians,” whose “combination of Faculties”—i.e., character traits supposedly revealed through cranial analysis—“create that cruel, bloodthirsty, and revengeful disposition common to the race.”

Fowler & Wells did not appear to mind how their skulls were acquired, as long as they added to the Cabinet’s overall effect. Their cold detachment also made the racism of the collection seem “scientific,” and masked the violence that produced it: Orson described Mangas Coloradas’s skull as “one of the best contributions to phrenological science possible,” for example, saying nothing of the trauma and suffering inflicted with his murder and mutilation. References throughout Fowler & Wells publications to “Indians,” “Eskimos,” and others suggest that Mangas was one among many indigenous people whose remains were stolen and displayed in the cranial collections, to say nothing of those from Africa, India, and other parts of the colonized 19th-century world.

It is still more or less legal to own human remains in the U.S., but there are important exceptions: the remains must have been acquired legally (i.e., no grave-robbing, murder, etc.); a handful of states prohibit or restrict the buying and selling of remains; and the remains cannot come from federally-recognized indigenous groups. The 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act made it illegal to traffic in such remains, and required museums to inventory and offer to repatriate them. The Phrenological Cabinet and its macabre curators are worth studying as influential and unusual 19th-century cultural phenomena, but the contents of the Cabinet are worth recovering because many of them could possibly be repatriated.

By the 1880s, the Cabinet had grown substantially, but phrenology itself was faltering. Lorenzo and Orson had set up independent offices in London and Boston, respectively, but Samuel Wells died in 1875. When her brothers died, Charlotte was left to run the family business, which now included a school, the American Phrenological Institute. She donated the massive Cabinet to the Institute, but begged supporters to help her buy or build a permanent structure to house the collection. It never happened.

After Charlotte died in 1901, Lorenzo’s daughter Jessie took over. Newspaper reports and business directories from subsequent years point to serious financial trouble. A 1919 Manhattan directory lists M.H. Piercy, Jessie’s brother-in-law, as the sole officer of Fowler & Wells, which is identified simply as a publishing company. In the 1920 census, Piercy lists his profession as “publisher.” In 1930, he changed it to “gardener.”

Throughout these years, the Cabinet’s contents disappeared. Stern, in her book, appears to offer the final word, asserting without citing a source that “eventually the collection of busts and crania was dispersed or destroyed.” It is possible some of the skulls may have ended up in medical schools, but unless the crania exhibited a unique pathology or trauma, they likely would not have been worth much to medical educators. Others could have made their way to anthropological collections at museums and universities, but few have been identified.

A few items have resurfaced. The New York Historical Society Museum acquired 27 Fowler & Wells masks and busts in a 1946 auction, and another from a private donor. The Morton Cranial Collection at the Penn Museum includes three casts, donated by Orson himself. (Interestingly, these are casts of skulls rather than faces or heads.) One additional piece, a replica of Fowler & Wells’s Aaron Burr death mask, is at Princeton University, and another, of Thomas Edison, is at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. One skull traceable to the Fowlers is in the Science Museum in London. It is a remnant of Lorenzo’s collection in England, rather than the larger Cabinet in New York, but its existence suggests that some crania may still be out there, dispersed but not destroyed.

The “knowledge” that phrenology purported to discover can itself be considered an artifact, a vestigial and troubling chapter in the history of ideas. While the loss of plaster casts of men like Peter Robinson is unfortunate, it may be nothing to mourn. But given the fact that Fowler & Wells collected numerous indigenous remains, which presumably have not been repatriated, the Cabinet’s fate remains a mystery worth studying and, hopefully, solving.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook