The French Missionary and the English Duke Who Saved a Chinese Deer From Extinction

A conservation tale 120 years in the telling.

When visitors enter Beijing’s Nanhaizi Milu Park, they step onto a long wooden bridge that stretches over a marsh. It’s the perfect place to see a herd of odd-looking deer in the distance—large and tawny, with big hooves, branched antlers, long tails, and shaggy coats. On a gray and blustery November afternoon, the deer are spending their time leisurely, placidly kneeling near feeders stocked with grass

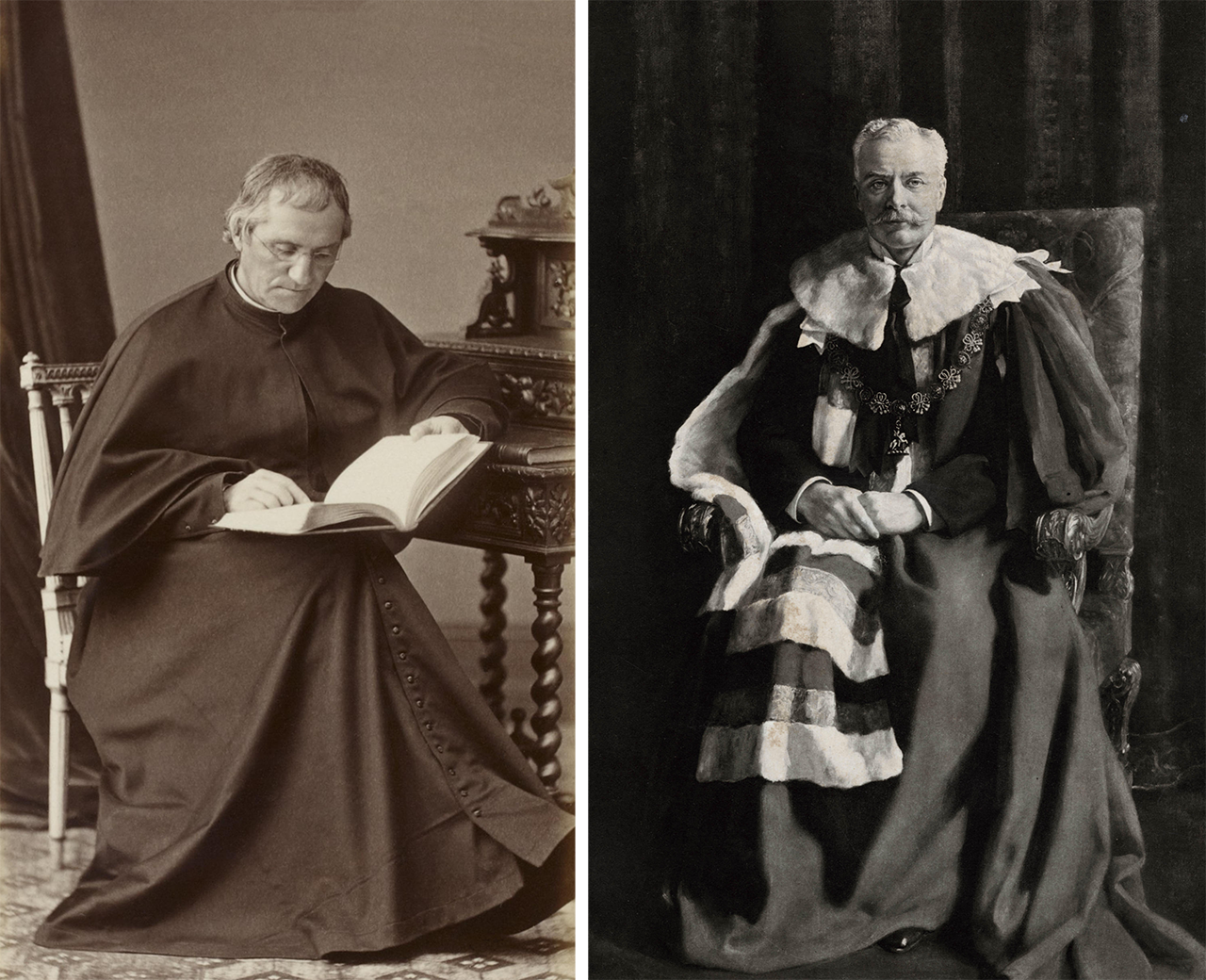

It’s a sight that wouldn’t have been possible 120 years ago. Though nearly 7,000 Père David’s deer roam the wetlands of China today, the species was declared extinct in the wild in 1900. Its resurrection is due to an unusual event in the annals of conservation—an accidental tag-team collaboration between a French missionary-cum-zoologist and an English duke.

Fossil evidence shows that Elaphurus davidianus were prevalent in China some 2,000 years ago. But by the time Father (Père) Armand David, the deer’s French namesake, visited China in 1861, hunting had reduced the population to a single herd—the one kept under armed guard on the imperial hunting grounds near Beijing.

David—also credited as the first European to see a giant panda—had been sent to China to spread Catholicism, but he ended up spending much of his time there collecting biological specimens that were new to Western science.

After a few years of traveling in China, David got wind of the emperor’s captive herd. The private grounds were exclusive to the royal family, and David was forbidden from entering. But he managed to sneak an illicit peek, and described what he saw in a letter to a colleague.

“This spring I was able to hoist myself onto the surrounding wall,” he wrote. “I had the good fortune to see, far from me, a group of more than a hundred of these animals.”

In Chinese, David wrote, the deer are known as milu or sibuxiang, meaning “not like the other four.” It’s an apt description for a visual frankenspecies, with the antlers of a deer, the head of a horse, the hooves of a cow, and the tail of a donkey.

After successfully bribing a few of the imperial guards, David managed to obtain a pelt and antlers, which he sent to the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. The specimens piqued the interest of the French scientific community, and in 1866 French and Chinese authorities negotiated the transfer of a handful of the deer to zoos across Europe.

It was lucky they did. In 1895, a dire flood ravaged much of the imperial hunting grounds, decimating China’s last population. A couple of years later, the few surviving deer in China were hunted down during the Boxer Rebellion, a civil uprising against foreign influence and the imperial elite.

Half a world away, Herbrand Russell, president of the Zoological Society of London and the duke of Bedford, heard about the species’ plight. He purchased the remaining 18 deer from the European zoos that housed them, and began raising them at his estate, Woburn Abbey.

“As a zoologist himself, Herbrand knew very well that the deer had no chance of survival with so few animals scattered around various zoos,” says Dominic Bauquis, who has worked to help conserve the species and is familiar with its history.* “While he did not know whether the species could be saved from extinction, he made a deliberate attempt to regroup them and give the Père David’s deer a chance.”

All current populations of Père David’s deer are descended from the small herd kept at Woburn Abbey—a herd that barely survived the two world wars. In the first half of the 20th century, food restrictions and wartime diktats saw English straw reallocated to military horses, and a particularly harsh winter nearly depleted the already limited supplies. After almost losing the species during World War II, the later dukes of Bedford exported some of the deer to zoos around the world.

One of those dukes was Robin Russell, Herbrand’s great-grandson, who dreamed of returning the deer to their homeland. He got the chance in 1985. With an economically developing China starting to focus on conservation and international collaboration, Chinese officials approached Woburn Abbey to discuss cooperating on a reintroduction of Père David’s deer.

That year Robin Russell traveled to China, where 20 of the deer were returned to the exact location that the species had last lived—the imperial hunting grounds in Beijing, which had since become a public park (now renamed Nanhaizi Milu Park).

But the park, located in a sprawling Beijing suburb, is limited in space. So the following year, China’s Ministry of Forestry teamed up with the World Wildlife Fund to transport another 39 deer to the Dafeng Milu Park on China’s eastern coast. The 300-square-mile reserve boasts coastal wetlands large enough to support populations in the thousands.

Conservationists at Woburn Abbey then worked to open another reserve in central China, where the deer would have historically roamed. In 1993, 34 deer were introduced to Shishou Milu National Nature Reserve.

In 1998, Père David’s deer were once again beset by severe flooding, this time at the Shishou reserve. The deer scattered into the surrounding forests. Instead of recapturing the animals, conservationists wanted to first see if the deer could survive in the wild.

To Bauquis’s delight, the deer thrived—back in the wild less than 20 years after being reintroduced in the country where they’d been extinct. “It’s a beautiful story on many levels,” says Bauquis, “and it shows what international cooperation can achieve.”

Today, Chinese researchers say there are roughly 70 parks with Père David’s deer, many successfully reintroduced to the wild. The Dafeng reserve is home to the largest population, with an estimated 6,000. Bauquis says the Shishou reserve supports between 600 and 1,000 deer, while Nanhaizi park is home to around 200.

Yuhua Ding, former director of the Dafeng reserve and a 30-year conservation veteran, describes the deer’s population recovery as “ideal”—meaning they’re breeding rapidly and, as of yet, not subject to disease—but notes that the species is still vulnerable. “Seven-thousand,” he says, “is a small number in terms of a species population.”

Monitoring the species’ genetics is key. Because these deer were brought back from such a tiny population, they’re at risk of what’s called inbreeding depression—adverse health effects caused by breeding between relatives. The smaller the population, the more likely the animals will be inbred. Given the minuscule starting point for Père David’s deer, it’s a small miracle that no signs have appeared.

But Ding says caution is warranted: The deleterious effects of inbreeding can take generations to manifest, making it imperative that wildlife managers keep close tabs on the current populations. To keep the deer healthy, conservation teams plan to transfer individuals between herds.

Researchers also want to know how the deer will adapt to their new habitats. These deer haven’t lived in the wild for ages, so scientists are curious to learn about their behavior in new surroundings—how they might respond to potential predators, such as tigers and wolves, what they’re eating, and how they’re mating.

Still, things are looking up for Père David’s deer. Most species pushed to the brink don’t have a resurrection story—a fact illustrated by the Nanhaizi Milu Park’s macabre extinction graveyard. A winding series of marble tombstones there mark the dodo, the Tasmanian tiger, and, midway through the queue, an erroneous placard that reads “Père David’s deer, 1900 extinct in China.”

One hopes that that’s the only premature gravestone at the site. The last tombstone in the series is marked “mankind.” Time alone will tell if it’s prescient or not.

* Update: This story has been updated to clarify a character’s involvement in the conservation process.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook